Issue 46

May 2023

ETHICALLY SPEAKING

By Anantharaman Muralidharan, Research Fellow at Centre for Biomedical Ethics, NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

Singapore plans to be a global leader in Artificial Intelligence (AI) by 20301. This involves, on the one hand, widespread deployment of AI in a variety of settings, and on the other, widespread trust in these AI solutions. Who do you think should be responsible when AI or algorithms malfunction: The programmer, manufacturer, or user?

Clearly that trust needs to be well-placed, but what does it mean for trust to be well-placed? Certainly, one part of this is these AIs getting things right reliably often. But that alone is not enough.

Consider a mechanic who you want to fix your car. No matter how often he properly fixes cars, if he refuses to take responsibility when he makes a mistake, you wouldn’t trust him to fix your car. This is because the ability and willingness to take responsibility is a key component of being trustworthy.

Yet this creates a conundrum: After all, AIs—at least of the kind we’re likely to see over the next seven years—are merely highly sophisticated programmes. They can no more take responsibility for mistakes than your computer, or your calculator can.

AI and cognitive technologies

Let us try to look closer at how we interact with calculators and computers, and other technologies that automate some of our thinking. We use computers for a variety of reasons ranging from gaming and connecting with other persons over the Internet to word processing, presentations and performing calculations.

When we use computers in these instances, does that count as trusting computers? Suppose that it does, why do we trust computers in these instances? After all, computers do crash with some regularity.

Plausibly, in most cases except when requiring it to perform calculations, we trust computers because we can immediately verify that the computer is doing what it’s supposed to. When we move our mouse, the cursor moves accordingly. When we press a key, the corresponding letter or number appears on our screen. When we click the corresponding button, our player character in the computer game moves accordingly. If it was not working properly, the screen would freeze or something else unexpected would happen immediately.

White-box or Interpretable AI: This, as noted, is so difficult that it would not be reasonable to hold programmers responsible if they made a mistake.

Even though many complicated operations are happening in the background, we can instantly verify whether the computer is working or not.

What about calculation cases? Consider cases where you use your calculator, or the calculator function on your phone or even the various functions in a spreadsheet. Why do we accept the answer in these cases?

One plausible reason why we trust calculators and computers on this score is that we trust the manufacturers and programmers.

Performing various mathematical operations strikes us as obviously being the kind of thing that can be done by a machine that knows only how to blindly manipulate symbols according to an algorithm. It does not require human judgment or knowledge of what those symbols mean.

By contrast, many of the tasks that we want AIs to perform do require judgment. To take just one example, treatment recommendations and medical diagnoses have an element of judgment whereby people bring together information from a variety of sources and put them together in complex ways.

It is no simple matter to explicitly spell out all the factors that could possibly apply in making a given diagnosis. This is likely to be true of many decisions in the areas like freight planning, municipal services, education, and border security. This complexity means that there is very little that manufacturers and programmers can meaningfully do to prevent a given malfunction.

White box, black box or grey box

To illustrate, consider one kind of AI model: white-box or interpretable AI. These types of AIs can be thought of as highly complicated computer programmes. For such an algorithm to get things right, the programmers must anticipate every eventuality and know how to specify which considerations are relevant and to what extent they are so in each situation. This, as noted, is so difficult that it would not be reasonable to hold programmers responsible if they made a mistake.

Consider, instead, black-box AI models: These models involve algorithms that are too complex to understand even for the programmer. This is because the programmer does not explicitly programme the algorithm.

Instead, the algorithm is trained on a large set of cases. The AI, over a large number of cases, is told what the right outputs are for a given set of inputs. The AI comes up with its own decision rule to match inputs to outputs. The hope, with these black-box models, is that it captures the subtleties of our decision making when we exercise judgment. The downside is that we do not know how the AI comes to a decision. Moreover, given how AIs are trained, they inherit all the biases that we have. For instance, consider ChatGPT by OpenAI. Despite the best efforts of programmers, the AI can still generate racist content2.

After all, without AI, it is these would-be users of AI who ought to take responsibility for their decisions. Technology cannot be a way for people to evade their responsibilities. This, however, has implications for what kinds of AI we deploy and how we deploy them.

There are other models called explainable or grey-box AI that attempt to achieve the best of both worlds. They start with a black-box model as a base and then use another AI to explain the decision of the first AI. With this, we might be able to know why a particular decision was made. However, we would still not be able to predict in advance how the AI will decide. Just because a black-box AI gives weight to certain considerations in one case, it doesn’t mean that the AI will give weight to those considerations in a similar case. And since the base AI is still a black-box model we would not be able to know how to train the AI so that it does not malfunction.

User responsibility

All this suggests that manufacturers and programmers cannot be held responsible for AI malfunction (except, perhaps in cases of egregious negligence). However, if not them, then who? One remaining plausible option is the users themselves. In some ways, this makes intuitive sense. After all, without AI, it is these would-be users of AI who ought to take responsibility for their decisions. Technology cannot be a way for people to evade their responsibilities. This, however, has implications for what kinds of AI we deploy and how we deploy them.

First, humans must be kept in-the-loop. Humans must be the final decision-maker in these scenarios. The outputs of AI can never be decisions as such, only recommendations. It would not make sense to hold users responsible for AI malfunction if they could not stop the AI from acting on its wrong decision. Thus, for instance, fully self-driving cars may have to be taken off the table. After all, to be ethically acceptable, drivers must be able to intervene anytime; they should be paying attention to the road. Yet, if they are already paying attention to the road, they might as well be driving the car themselves.

Second, not only should humans be kept in-the-loop, AIs would be useless if people had no way of deciding whether to follow the AI’s recommendations. Moreover, being kept in-the-loop would be pointless if people simply rubberstamped the AI’s decision. This means that black-box models are also out of the question.

The right kind of AI

Our trust in AI is a matter of trusting the user. AIs after all, do not understand reasons and cannot be said to properly respond to them. Importantly, AIs cannot take responsibility for mistakes.

AIs, to be trustworthy, must be the kind that can aid human users in making sound decisions. As Singapore moves forward in embracing AI, it is important that we do so in a way that is informed by the right understanding of what makes people and technology trustworthy.

https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/files/publications/national-ai-strategy-summary.pdf.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/openais-impressive-chatgpt-chatbot-is-not-immune-to-racism.

More from this issue

ETHICALLY SPEAKING

The Petrov Dilemma: Moral Responsibility in the Age of ChatGPT

A WORLD IN A GRAIN OF SAND

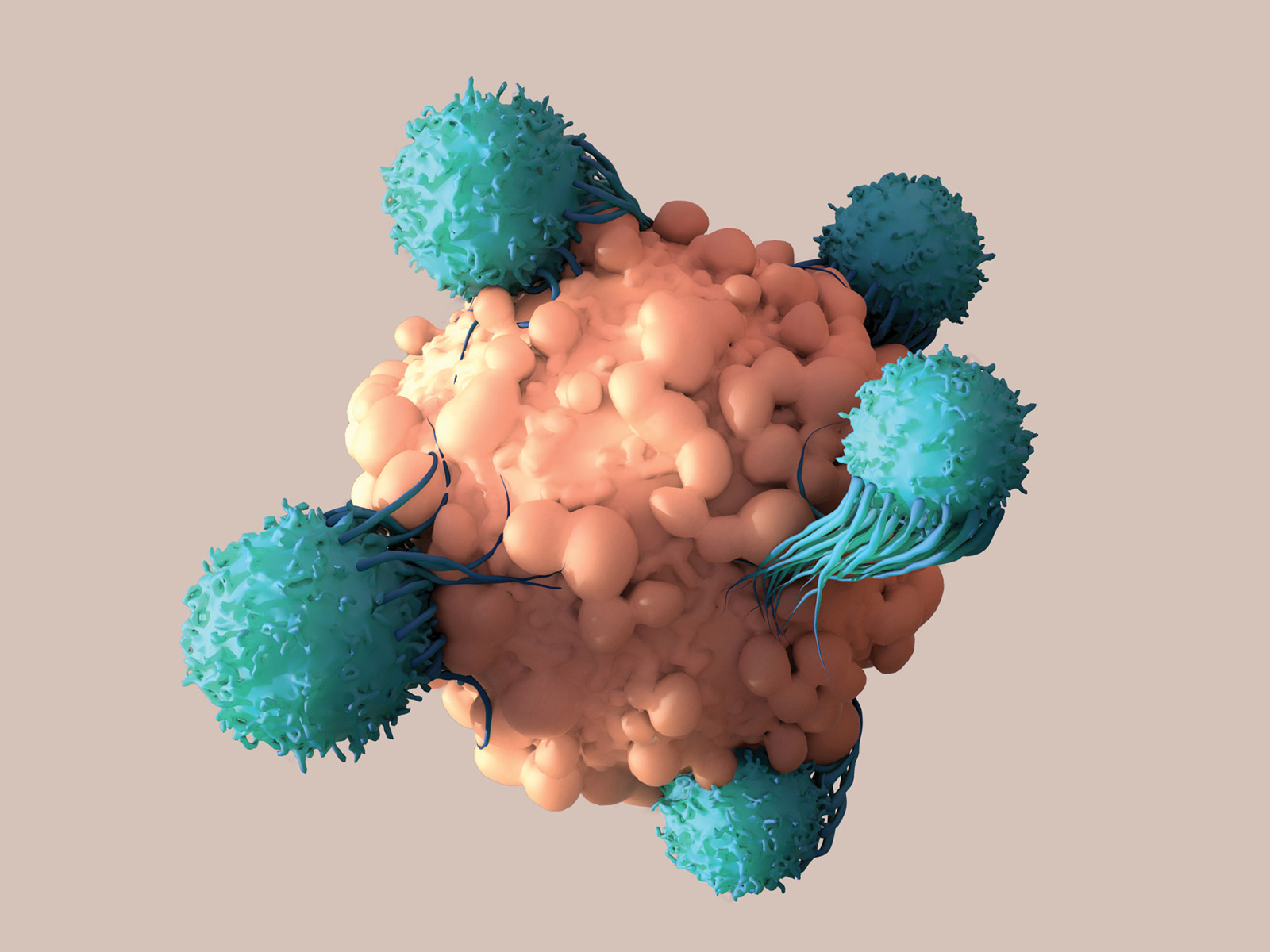

The A to Z of T cells

ALUMNI VOICES

She’s a Diver-doctor in NDU