Issue 43 / August 2022

IN VIVO

Deeper Understanding of Agitation Management through Virtual Reality

Empathy can be a touchy subject for healthcare workers—how can one possibly hope to understand what a patient is feeling, especially in times of duress when they become increasingly agitated or frustrated, or when physical restraint is required?

ow then, can one even impart learned knowledge and experiences of such an abstract concept as empathy?

In their software—Virtual Reality in Agitation Management (VRAM)—Assistant Professors Cyrus Ho and Shawn Goh, along with their team, EMART, hope to help future generations of healthcare workers understand what it is like to be a frustrated and agitated patient, by walking a mile in such a person’s shoes.

An increasing number of healthcare workers are facing problems with agitation management and experiencing difficulty in managing them appropriately, resulting in a number of them being injured or traumatised, says Asst Prof Ho.

Patients may also be harmed emotionally because of inappropriate physical restraints being applied to them. They may also have been hurt because of inappropriate remarks by healthcare workers.

“In our current medical and nursing curricula, we don’t really give students a holistic overview of how we should be managing such situations, and there’s also no dedicated programme for it,” says Asst Prof Ho.

“So that’s why we decided to do something that has a blended learning approach, combining theoretical knowledge—a didactic lecture—and roleplay, and then ultimately adding on the virtual reality (VR) perspective to it.”

VRAM, which won the Grand Prize for the Medical Education Grand Innovation Challenge (MEGIC), AY 2020/2021, aims to teach students and staff across healthcare disciplines effective agitation management using empathic means, through an amalgamation of traditional teaching and technology. VRAM is introduced as part of a module called “Managing Aggression using Immersive Content (MAGIC)”, which comprises a didactic lecture and role play.

Asst Prof Ho spearheaded the initiative, providing direction from a psychiatrist’s perspective, with Asst Prof Goh guiding the project from a nursing perspective. Having spent time in the fields of education and healthcare, the two teachers drew on their own clinically relevant experiences with patients, and included elements to bridge the gap between curriculum and students that were otherwise difficult to convey through conventional teaching.

Other members of Team EMART, NUH Nursing staff Ms Cecilia Chng and Mr Philip Ong, also channelled their input from a nursing perspective on agitation management, while Dr Cheryl Chang from NUH Department of Psychological Medicine provided perspectives from a junior doctor’s point of view. Medical students Tricia Ng and Ernest Yang provided input as medical students, while Cherine Fok from NUS Medicine Department of Psychological Medicine bolstered the team with administrative and logistical support.

VRAM runs on the Oculus Quest 2 VR system as it is a standalone headset that does not need to be connected to any desktop, making the software easily accessible to students who wish to borrow it to practise the game at home. An external vendor was commissioned to help develop the programme, with the NUS IT team providing technical support and advice.

The VR game within VRAM, called Finding Debbie, puts the viewer into an interactive, dynamic storyline within a VR world. The viewer—who plays the role of an on-call healthcare worker in charge of a ward—is asked to assess a patient who grows increasingly aggressive and disoriented.

Joining the dots

The viewer is tasked with de-escalating the situation, removing stimuli that could possibly further agitate the patient, while piecing together what the patient could be feeling through contextual and behavioural clues.

The virtual patient the viewer is attending to would also be experiencing a drug-induced psychosis—complete with hallucinations and paranoia—having entered the ward after being found by passers-by on the road.

Distractors typically seen in an on-call setting are included in the virtual environment, including other nurses requesting the viewer to attend to tasks, a family member of another patient requesting updates and a TV in the background with its volume turned up.

“We see this very often in clinical practice,” says Asst Prof Ho.

“We wanted our students to go through a scenario with things that are commonly encountered—they have to learn to use verbal de-escalation, choosing the right words to talk to the patient, they also have to learn to take away objects in the scene that could potentially be used as weapons against other patients or against ward staff.”

The viewer will have to make medical decisions, such as the correct dosage of medication, and the right time to administer treatment, physical restraint, or a combination of both to the patient.

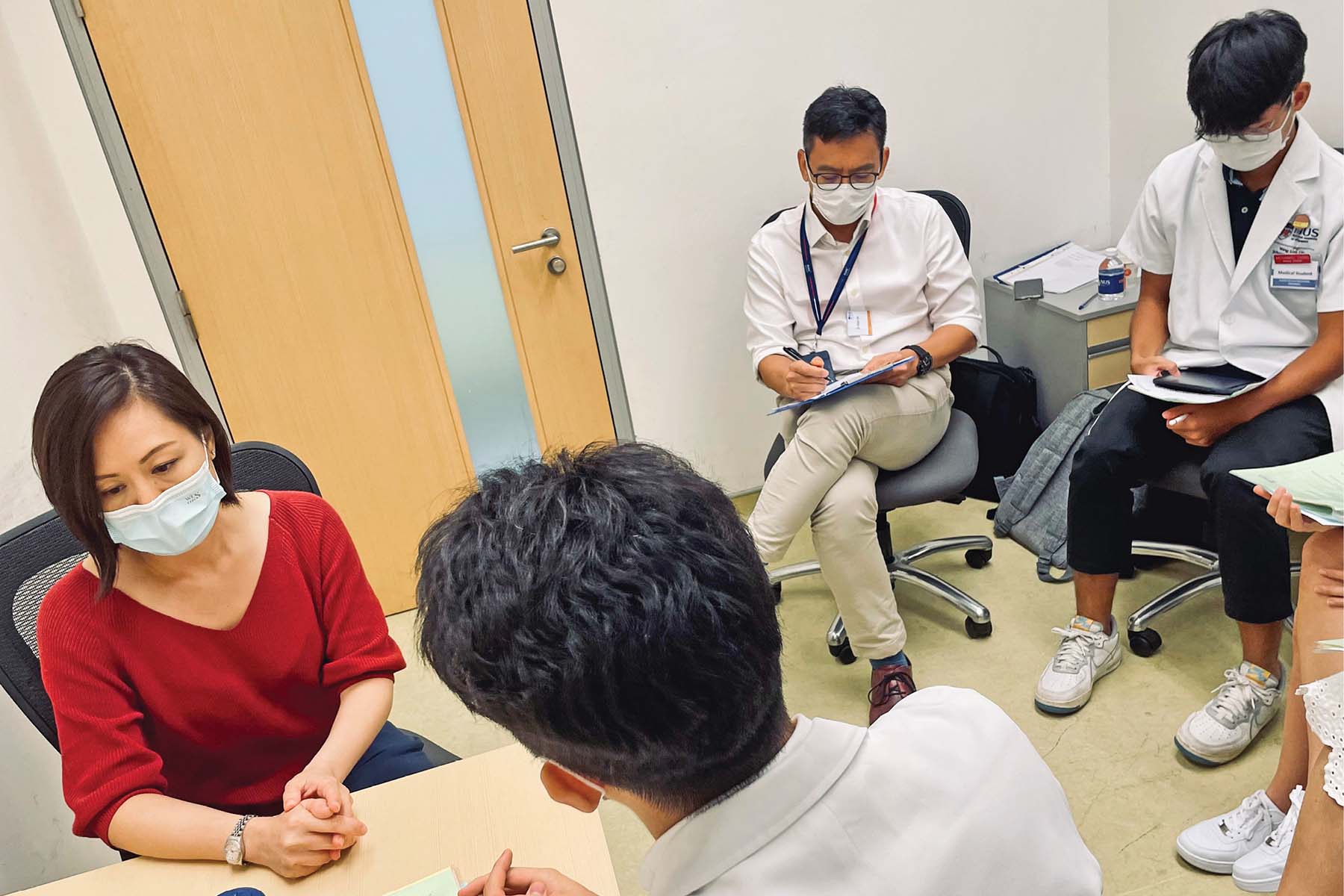

Assistant Professor Shawn Goh (second from left), Assistant Professor Cyrus Ho (third from left), as well as NUS Medicine and Nursing students.

The scenario also includes ethical dilemmas, such as whether to covertly administer medication to the patient or discharging her against advice, as well as principles of medical ethics such as autonomy, where a patient has the right to refuse treatment, non maleficence, where a healthcare practitioner should not cause harm, and beneficence, where healthcare practitioners should act in the best interest of the patient.

However, a major part of the story lies in the smallest of cues that the viewer has to interpret and uncover in order to fully understand the patient’s motivations (no spoilers here!).

“In the VR scenario, we give them the opportunity to choose the most appropriate reaction, with consequences if you choose the wrong one—but it’s safe, you don’t cause harm to anyone,” says Asst Prof Goh, adding that the viewer will then learn the appropriate action to take in the future—which is how they decided on the direction of VRAM’s teaching pedagogy.

He notes that more importantly, both medical and nursing curricula now aim to train future generations of healthcare workers to exercise compassion and empathy.

“Moving forward, we will see more patients with such needs, and healthcare workers need to have an empathetic response. So VRAM implicitly teaches this compassion which we hope to inculcate in future generations of healthcare workers.”

“This programme is not just about managing agitation,” says Asst Prof Ho.

“It’s also about helping students to recognise how their actions have implications for patients and how they feel. It teaches students to use the appropriate mannerisms and responses for patients like this.”

EMART also plans to begin exploring a second scenario, where viewers would experience life from a first-person perspective of a patient dealing with healthcare workers.

Viewers would go through what it feels like to be misunderstood, and how to deal with hallucinations, delusions and even physical restraint. This would help them understand patients better and increase their empathic responses.

Asst Prof Ho hopes VRAM can be further implemented in the future, possibly as a workshop, for healthcare workers to advance their learning in the area of empathy and agitation management. This would mean reaching not only nursing and medical students, but also junior doctors and nurses in hospitals.

Click here to watch how VR helps students manage agitated patients with empathy.