Issue 43 / August 2022

All In The Family

“What Matters Most”: Listening for the Patient’s Voice in Medical Training and Clinical Practice

By Dr Victor Loh, Assistant Professor and Education Director of Family Medicine, NUS Medicine; Dr Yew Tong Wei, senior Consultant Endocrinologist at National University Hospital (NUH); Dr Choong Shoon Thai, Family physician at Jurong Polyclinic, National University Polyclinics (NUP); and Dr Tan Wee Hian, Consultant Family Physician and Head of Pioneer Polyclinic, National University Polyclinics (NUP)

“How do we listen out for what matters most when doctors are so rushed at the polyclinic?”

his was at the tail-end of the day-long motivational interviewing workshop in the Family Medicine (FM) posting and I was thinking to myself: “Now how do I respond to this student?”

How indeed may polyclinic physicians contending with queues of patients living with long-term conditions, within allotted 10-to-12-minute consultation windows, go through the following: explain investigation results, explore outcome targets, disentangle medication side-effects, perform a focused physical examination, address disease complications and clarify follow up plans? And how should or could physicians still carve out time to actively listen, reflect, affirm, and elicit those aspirational goals that would spur patients to exercise regularly, eat healthily, lose weight, forgo cigarettes, and propel all manner of behaviour to positively impact their health?

It was a conversation along a corridor a number of years back that then-assistant dean Associate Professor Lau Tang Ching popped the question which started us teaching students to listen to what matters most to patients: “Victor, how about teaching motivational interviewing in the FM posting?”

Motivational interviewing training

Motivational Interviewing (MI), an evidence-based approach for positive behaviour change has grown in traction as an effective intervention to improve health outcomes. Miller and Rollnick, the promulgators of MI in the 80s, described it as a “collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion.”

We wanted future doctors to be curious about a patient’s experience of illness, to give voice to that experience, and to respond skillfully to what they hear.

So, after attending hours of training by the Health Promotion Board (HPB), nights of reading books bought off Amazon, multiple conversations with local MI champions, and even more conversations with stakeholders, we were ready to launch the MI workshop for medical students. It would comprise training videos, verbatim transcripts, live demonstrations, student role plays, standardised patients, feedback, and more feedback.

Dr Victor Low facilitating a training workshop for students doing their Family Medicine posting.

With the explicit intention of addressing the often-one-sided doctor dominated conversations in time-pressed clinical consultations, we felt it important to train our learners to weave into their communications repertoire MI elements of reflective listening: first to content heard in the patient’s narrative, and then more deeply to the feelings and tacit meanings of what was being conveyed within the doctor-patient dyad. Learners and faculty staff took some time to get accustomed to this practice; it takes training and effort to listen beyond clinical content to excavate affective content and “what matters most” to patients. We wanted future doctors to be curious about a patient’s experience of illness, to give voice to that experience, and to respond skillfully to what they hear.

The initial run of the MI workshop was largely well-received. After undergoing several iterations, it is now an OSCE (objective structured clinical examination) assessment item in the FM posting (since AY2017/18), and a fixture and hallmark of the NUS Medicine curriculum. Interest among school-based health screening projects has resulted in it being embedded in the informal curriculum of a broad range of NUS Medicine community involvement projects (CIP).

The initial run of the MI workshop was largely well-received. After undergoing several iterations, it is now an OSCE assessment item in the FM posting (since AY2017/18), and a fixture and hallmark of the NUS Medicine curriculum.

Person-centred care

“Person-centredness” sits close to the heart of Medicine. Widely written about in the healthcare literature, one of its early proponents was American Carl Rogers whose humanistic psychology viewed persons as beings inherently motivated toward personal growth and development. His work has spawned learner-centred teaching in the education sphere, and person-centred care and shared decision-making in the medical sphere. Enshrined in conceptual frameworks such as Mead & Bower’s “patient-centred care”, and in the Pendleton Consultation Model endeared by family physicians, shared decision-making hinges on supporting patients in decision-making, and on understanding that such decisions rest on the quality of exploration and response to “what matters most” to patients as autonomous individuals.

Year of Care Partnerships (YOCP)

I first met Nic and Lindsay in 2018 when they trained a number of NUP/NUHS physicians to become Care-and-Support-Planning practitioner trainers at Pioneer Polyclinic. Nic and Lindsay brought with them extensive experience training and supporting General Practitioners in Care and Support Planning (CSP) under Year of Care Partnerships (YOCP) in the UK’s National Health Service.

YOCP answers the question: how could patient care be different if existing resources expended in one year to care for patients living with diabetes (and other long-term conditions) was reconfigured so that better health outcomes could be attained? After over a decade of iteration in the UK, the YOCP approach features training practitioners in elements of motivational interviewing. This is so that “what matters most” to persons living with diabetes and other long-term conditions may be elicited, but which on its own is inadequate for patient-centred care to occur.

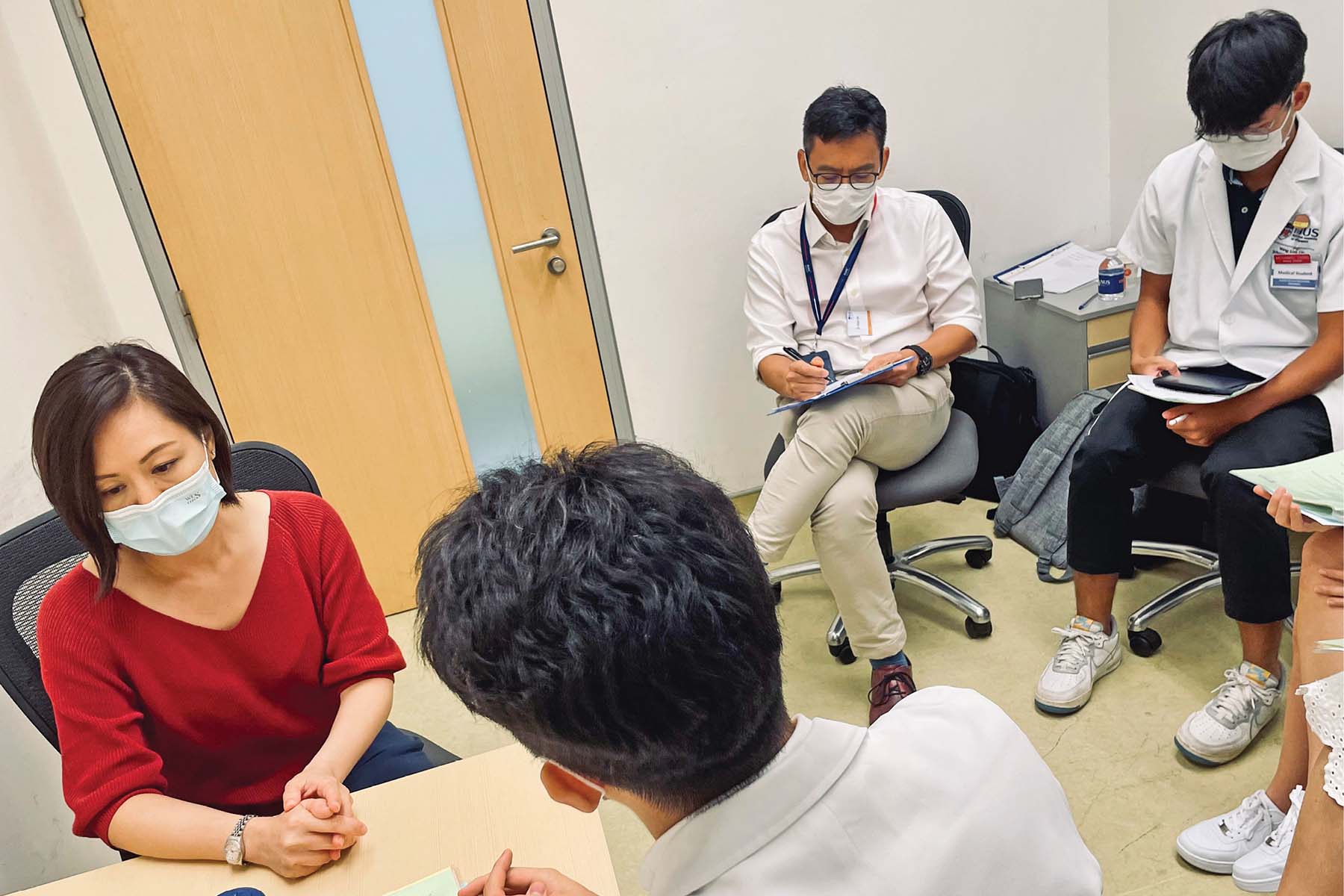

Dr Victor Low supervising 3rd year student, Bryan Peh, as he put his MI skills to practice with a Standardised Patient (SP) during his Family Medicine posting.

Crucially, YOCP also added health system enablers so that practitioners could more readily place patients in the driver’s seat of self-management and support decision-making for their long-term conditions. The YOCP approach to foster person-centred care through CSPs includes:

|

• |

The Trained CSP Practitioner: CSP practitioners are trained to facilitate conversations with prepared patients so that “what matters most” to patients may truly be at the centre of the shared decision-making, goal setting and action planning process. These involve elements that correspond with, and are not exclusive to, MI training. |

|

• |

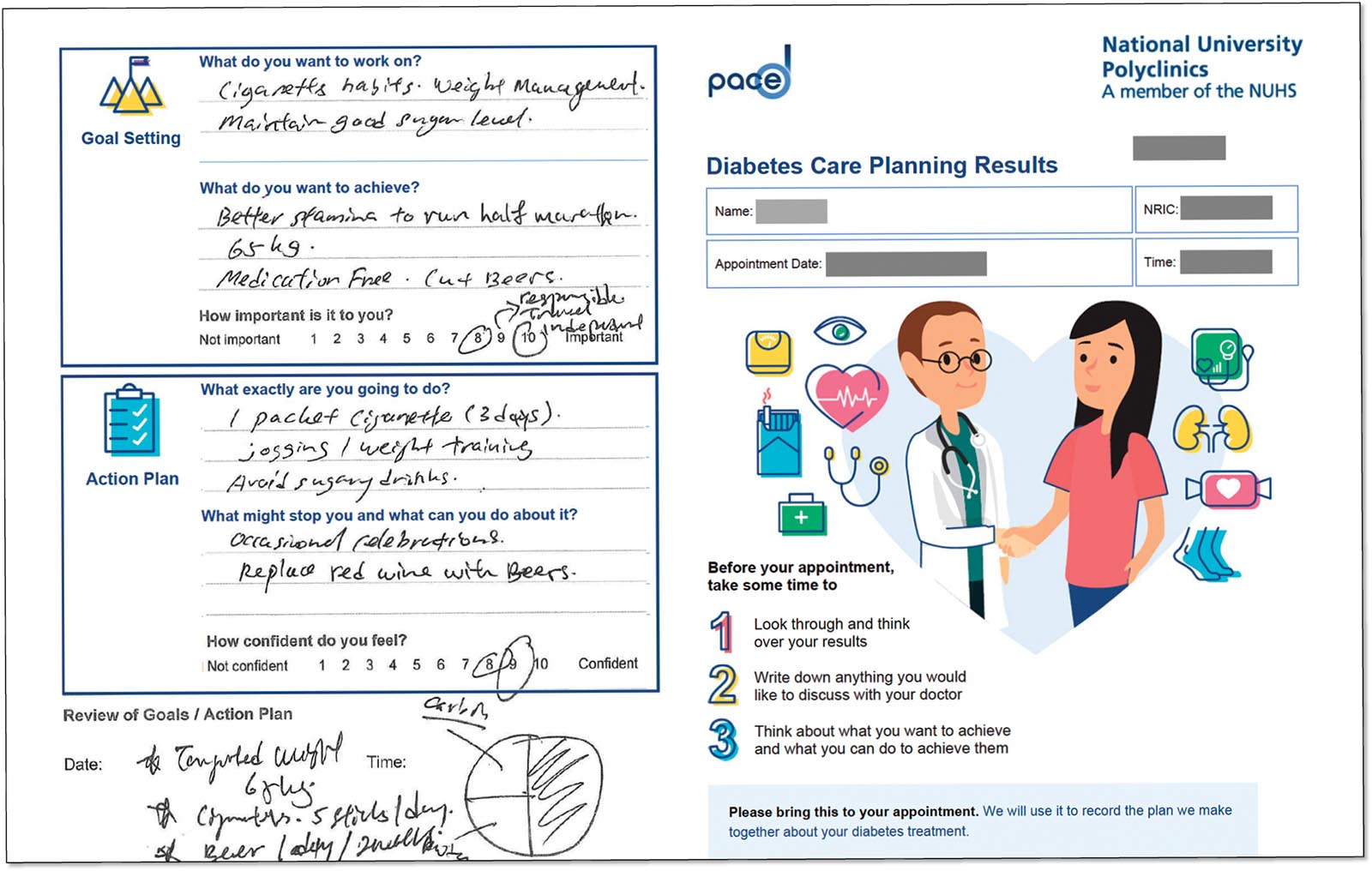

The “Prepared Patient”: Patients enrolled in the CSP process are prepared for a meaningful discussion with the CSP practitioner by having mailed hardcopies of the care planning letter containing the latest battery of investigation results and health outcomes mailed to them two weeks before the designated “CSP conversation”. The letters serve as reflective and discussion prompters for patients, who may attend consultations with trusted family members, so that concerns and decisions to be considered may be raised before the CSP. |

|

• |

Health system redesigned to elicit “what matters most”: As a CSP practitioner at Pioneer Polyclinic, I have found that the 20-30 minutes set aside for each CSP has given me time enough to work with patients on “what matters most” while minimising any guilt around eating into subsequent consultations, or worse, over-burdening colleagues with additional patient-load. In addition, the presence of a coordinator who ensured care planning letters were dispatched on time, and who would inform, educate, and even coach patients before and after the CSP conversation made a huge difference in nudging patients along in working towards care goals. |

Excerpt from a Care and Planning letter with actual entries by a (deidentified) patient.

Patient voice: Time and space needed

It has been three years since Care-and-Support-Planning for Diabetes has been rolled out at the National University Polyclinics (March 2019). Preliminary programme evaluation results are indicative of positive patient experiences, with some patients reporting increased agency and involvement in decisions around diabetes self-care. At time of writing, the results of the main evaluation study for PACE-D (Patient Activation and Care Empowerment for Diabetes) are being analysed.

What we have learnt is that if we truly believe in the benefits of patient-centred care and hearing the patient voice, then the active listening and facilitation skills of motivational interviewing need to be given the time and space for its use in clinical practice.

I return to the question posed at the beginning of this article:

“How do we listen out for what matters most when doctors are so rushed at the polyclinic?”

What we have learnt is that if we truly believe in the benefits of patient-centred care and hearing the patient voice, then the active listening and facilitation skills of motivational interviewing need to be given the time and space for its use in clinical practice. The YOCP approach to Care-and-Support-Planning with patients receiving the care planning letter two weeks prior to the CSP and a spacious 20-30 minutes for CSP conversations, is clearly one such approach to set aside time so that the patient’s voice may be heard.

Care and Support Planning (CSP) trainers Dr Nick Lewis Barned (third from left) and Ms Lindsay Oliver (middle) flanked by Dr Victor Loh, Dr Yew Tong Wei, Dr Choon Shoon Thai and Dr Tan Wee Hian, with nurse clinician Yap Hwee Luan (second from right) and assistant nurse clinician Sapta Haji Ahmad (first from right) during a CSP training at NUP Pioneer Polyclinic.

As medical curricula, CSP practitioner training, and healthcare processes further evolve, perhaps the day the patient’s voice and person-centred care becomes the norm in daily clinical practice may not be too far off.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the army of facilitators, tutors and standardised patients that has enabled us to train and assess 300 medical students in motivational interviewing each year at NUS Medicine. Likewise, my thanks to CSP trainers Dr Nick Lewis Barned and Ms Lindsay Oliver, our mentors Profs Tai E Shyong and Doris Young, and my co-authors and CSP co-trainers with whom I have learnt much about patient-centred care.

At the time of writing, the PACE-D team won the Mochtar Riady Pinnacle Team Award for the systematic implementation of Care and Support Planning of diabetic patients at NUP Polyclinics.