Paradigm Shifts in Medical Education

The 3½-year Japanese Occupation had brought medical education practically to a standstill in Singapore. Ironically,it sparked a paradigm shift in the thinking of the local medical community that would help shape the future of medical training here.

Dr Chew Chin Hin, Past Master of the Academy of Medicine, gave an insightful account of this when he delivered the 18th Gordon Arthur Ransome Oration on 19 July 2007. With the expatriate doctors interned by the Japanese during the war, local doctors and staff had assumed full responsibility in running the Tan Tock Seng and Kandang Kerbau hospitals, the two that were left to serve the locals.

He recounted that this had led to the local doctors and staff being drawn much closer to each other. In addition to discussing their patients, teaching and learning, they talked about “practical policies which they felt deeply about well before and during the war; for example, the imperative need for a unified service with equal treatment of local and colonial doctors”, said Dr Chew.

When the war ended, the colonial government agreed to unify the medical service but took three years to implement the scheme. As for postgraduate specialist training, limited numbers of doctors were sent to Britain on scholarships to attend courses but they received little training, observed Dr Chew in his speech. It is noteworthy that before 1960, there were fewer than 50 doctors who had higher specialist qualifications to serve the population of two million.

Dr Benjamin Henry Sheares, an eminent obstetrician and gynaecologist who later became Singapore’s second President, wrote that “the Japanese invasion caused a general awakening of the people of Malaya. In no small measure did the local graduates contribute to this awakening, for they were able to show that, despite having been deliberately excluded from the higher echelons of the medical service, they were able, by making full use of their talents and by sheer grit, to run the hospital services as efficiently as possible under those unfavourable conditions”.

These were heady times for Dr Sheares and his medical peers, like Benjamin Chew, Ernest Monteiro, K. Shanmugaratnam, B.R. Sreenivasan, Wong Hock Boon and Yeoh Ghim Seng. There was no turning back the clock. The founding of the Academy of

Medicine in 1957 was an important milestone, with founder members like Professor Gordon Arthur Ransome, Dr Sheares and Dr Yeoh. In 1961, the Academy formed the Committee of Postgraduate Medical Studies which later became the School of Postgraduate Medical Studies, which in turn became the Division of Graduate Medical Studies in the National University of Singapore.

Time for a hair wash

Nurses used this stainless steel jug and basin combination to wash patients’ hair in bed up to the 1970s. The basin held warm water and the jug was used to pour some onto the patient’s head which was tilted over the side of the bed. Soap was then applied and rinsed off. How did the nurses prevent a watery mess? They draped a plastic sheet under the patient’s head and shoulders to channel the water into a pail. Nowadays, hospitals have shower facilities adapted for bed-bound patients.

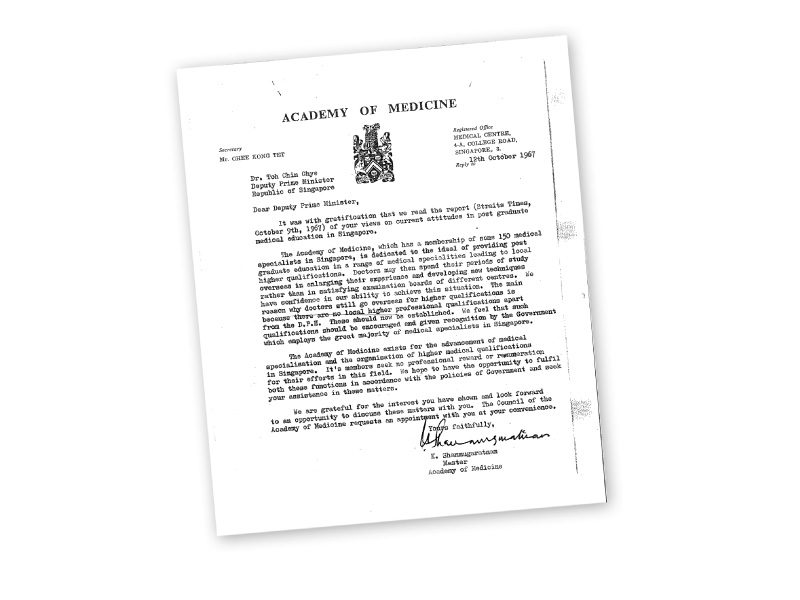

For the record… when Deputy Prime Minister Toh Chin Chye asked the Academy of Medicine in 1967 why they were not making any progress in the field of higher professional education, they sent him a letter (above) requesting a meeting with him. That meeting led to the Committee on Medical Specialisation being set up.

By the mid-1960s, local specialists had begun to make their impact felt. In the general hospitals, they led the way in pioneering procedures for treating complex medical problems in Singapore.

The nation’s first open heart surgery procedure, on 28 January 1965, was performed by a team led by Dr N.K. Yong. As part of the preparation for this surgery, he had trained for a year from mid-1962 in the United States (US) and then spent another year training the surgical team. Under the supervision of Dr Dwight McGoon from the Mayo Clinic in the US, Dr Yong and his team sealed two holes in the heart of Miss Chua Ah Moi, then 23, with the help of an artificial heart lung machine.

Two other operations followed quickly, both on children with the same condition, in February and March 1965. Following this success, SGH set up its coronary care unit in 1967. These services would be transferred in 1994 to the Singapore Heart Centre, renamed the National Heart Centre Singapore in 1998.

The Government too had a vision of Singapore as a medical training centre for the region. In the words of Dr Toh Chin Chye (then Deputy Prime Minister), the aim was to have medical services which were “second to none”. In his 8 October 1967 speech at the 62nd anniversary of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Singapore, he censured the school for having “grown older but not wiser”. He questioned the wisdom of doctors preferring to go to London, Edinburgh, Glasgow or Dublin for their specialist training, adding “it was time to consider seriously how Singapore could offer postgraduate studies to students with the necessary facilities”.

His criticism drew an immediate response from the Academy of Medicine. The Council, led by its Master Dr Shanmugaratnam, wrote to Dr Toh declaring its commitment to the “advancement of medical specialisation and the organisation of higher medical qualifications in Singapore”.

A morning coffee meeting on 4 November 1967 between Dr Toh and the Academy’s council members resulted in a letter being sent to Health Minister Yong. The letter suggested that “higher professional qualifications in various clinical specialisations be awarded by the University and that the School of Postgraduate Medical Studies be reconstituted to enable the Academy to participate as equal partners in the training programmes and examination.

Things moved quickly after that. Dr Toh became vice-chancellor of the University of Singapore in April 1968 and pushed through significant changes in the statute of the medical school, chairing the new medical school board himself. In 1970, Health Minister Chua appointed a Committee on Medical Specialisation to recommend a programme of medical specialisation that would “meet Singapore’s needs, and to make the republic an internationally pre-eminent centre for treatment, training and research”.

Mr Chua said the Government had to take the lead because “the private sector will not for a very long time be able to develop the very sophisticated specialities such as radiotherapy, neurosurgery and cardiac surgery which involved extremely high capital cost.

The committee’s report was accepted and the specialities recommended were quickly introduced – neurosurgery, cardiothoracic surgery, plastic and reconstructive surgery, nephrology and paediatric surgery. These were in addition to ongoing sub-specialisation within the general specialities, including urology, hand surgery, microvascular surgery, gastroenterology, endocrinology, oncology, respiratory medicine and reproductive medicine.

Through much effort, the acquisition of specialities and sub-specialities gained brisk momentum. For example, patients with chronic renal failure were offered new hope in 1968 when the first two patients started regular haemodialysis in SGH. Two years later, SGH carried out Singapore’s first renal transplant and, in 1977, the first two living-related renal transplants were performed, making the living-related donor transplant programme a success.

Limb reattachment surgery also made its mark when Alexandra Hospital, by now serving civilians after it was handed over by the British military, conducted the first such procedure of its kind in Singapore in 1975. Surgeons successfully re-attached 17-year-old Wong Yoke Lin’s arm after it was torn off at the elbow when she tried to remove a jammed piece of wood from a machine she was tending at a plywood factory. Doctors at Alexandra Hospital used their medical skills and a bit of improvisation, which eventually allowed the Ipoh girl to regain the use of her arm – the reattached arm had grown cold and turned white and various attempts to resuscitate it failed until one doctor hit on the idea of soaking it in a pail of warm water to encourage blood flow.

Mission possible… set up in 1923, St. Andrew’s Mission Hospital had 60 beds exclusively for women and children.

Change was also underway in the philosophy behind provision of care for mental health patients. Prior to the 1970s, such patients could only look towards custodial care. However, the introduction of tranquilisers in the previous decade had helped to stabilise many patients, allowing them to be discharged. It also allowed the hitherto forbidding – in the eyes of the public at least – hospital to gradually remove the metal bars on many of its doors and windows.

As the years passed, there was growing recognition in the medical community that many mental patients could be rehabilitated and reintegrated into normal social life. This,

coupled with better public understanding of mental health issues and hence lessening prejudice, would eventually lead to the creation of the Institute of Mental Health.

Hospital infrastructure and its adequacy to provide modern medical care also came under scrutiny and revamp. In 1971, a firm of consultant planners was hired to ascertain the requirements for hospital services over the next 20 years, to plan for these needs and to redevelop SGH. The report was completed in April 1972 and approval was given in November of the same year for construction of a new hospital in the Outram Road area.

The foundation stone of the new SGH was laid in 1975 and its doors were opened on 12 September 1981 by Prime Minister Lee.

Caring for the Community in Different Ways

Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital, Mt Alvernia Hospital,

Muslim Missionary Society of Singapore (Jamiyah)

A century of care

Dr Ow Chee Chung,

CEO, Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital

A GROUP of Cantonese immigrants founded Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital (KWSH) 105 years ago to look after the poor and needy in their community. When Tan Tock Seng Hospital relocated to Moulmein in 1909, the land was sold to KWSH via the Kwong Wai Shiu Free Hospital Ordinance by the colonial government for 99 years at a nominal price… and we have been here at Serangoon Road since.

Over the years, more buildings were constructed thanks to funds raised by the Cantonese community. Around the 1950s, a garden pavilion was added for patients to relax in. Using mainly traditional Chinese medicine, we provided outpatient and in-patient treatments for tuberculosis patients as it used to be a chronic ailment among immigrants. We also had maternity services from the moment we started this hospital.

During the Second World War, we were lucky that the Japanese forces did not take over the hospital and we could continue to serve the community. After the war ended, we tried out a lot of new services. By the 1970s, we had both Western and Chinese medical services. Since 2006, we have had a special tie-up with the National Cancer Centre Singapore to look after cancer patients too.

Nowadays, we serve the whole community regardless of ethnicity and we’re going into the next phase of medical services by building a 12-storey nursing home which will be ready by the end of 2017.

Sisters of substance

Sister Agnes Tan

Former nurse and midwife at

Mt Alvernia Hospital and

Regional Superior of Franciscan

Missionaries of Divine

Motherhood (Malaysia/Singapore)

OUR pioneer Sisters, the British and Irish Sisters of the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood, were part of Tan Tock Seng Hospital when they came to Singapore in the 1930s. When I started working alongside the Sisters in the Mandalay Road Hospital in 1948, I knew right away that I wanted to join them.

In 1950, I was among the second group of nurses recruited by the Sisters and went to England for training. We were very poor. The Sisters received expat salaries for their work in Tan Tock Seng and all those salaries went into a kitty that was used to build Mount Alvernia Hospital. Once the hospital was built – it opened on March 4, 1961 – the kitty was empty. The Sisters lived on the top floor and we only charged the patients $10 a day. Whether you were rich or poor, anyone could come; quite a number of people who came to the hospital had no money.

One of these patients was a very pregnant lady who took our wood meant for the construction of one of the hospital’s extensions. She told the Mother Superior at the time that her husband was a drunkard, she had eight children at home, about to give birth to the ninth child and there was no money. The Mother Superior told her to have her baby at the hospital and we wouldn’t charge her. We put her in one of our small single rooms and, because she didn’t have enough breast milk and was so poor, we also provided baby formula. When she was going home, we gave her milk powder and told her to come to us when she was short of milk. Every time she came, she would pick flowers and bring a bunch to us. She was grateful for what we did for her.

That was part of our start as a hospital and even though it was hard, we just did it. I am very proud of Mount Alvernia and how far we have come.

Serving the society

Dr H.M. Saleem

Vice President I,

Muslim Missionary Society

of Singapore (Jamiyah)

WHEN Jamiyah was founded in 1932, our mission was to support the Muslim community in spiritual, educational and welfare matters. We were known then as the All-Malaya Muslim Missionary Society with branches in the various states of Malaysia. After the separation from Malaysia, we changed our name to the Muslim Missionary Society Singapore but we remained cordial with our former Malaysian branches.

Our real push to serve the community better began in the 1970s when Haji Abu Bakar Maidin took over as president of Jamiyah. Then we had 190 members and about $5.60 in our fund. Now we have over 30,000 members and we have more about $17 million a year to fund our projects. In 1975 we started our free medical clinic in Geylang, staffed by volunteer doctors and nurses. We felt we needed to help the very poor and needy members of the community. We also started a whole range of welfare homes and residential services like the Jamiyah Children’s Home for orphans, Jamiyah Home for the Aged, Jamiyah Nursing Home for those needing long-term nursing care and Jamiyah Halfway House for recovering addicts. Our home for the aged is open to all Singaporeans.

Now we are embarking on expanding and upgrading our services to meet the needs of the ageing population. We are planning another nursing home and renovating our current residential medical nursing home, Darul Syifaa. Thanks to the support from the community and the Government, Jamiyah has overcome many challenges in its quest to help Singapore be a better society.

“Caring for our People: 50 years of healthcare in Singapore”; reprinted with the kind permission of MOH Holdings Pte Ltd on behalf of the Ministry of Health.