Has Medicine Sold its Soul?

“This was not guilt: guilt is what you feel when you have done something wrong. What I felt was shame: I was what was wrong.” Atul Gawande – Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science

The practice of medicine is fraught with psycho-social-legal uncertainties and complexities that range from the unusual to the subliminal. Right or wrong? Now or never? To tell or to keep quiet? To carry on or to discontinue? A biomedical ethicist discusses the existential dilemmas confronting doctors, while a clinician highlights challenges faced by healthcare professionals here in the course of their work and identifies pathways to their resolution.

HAS MEDICINE SOLD ITS SOUL?

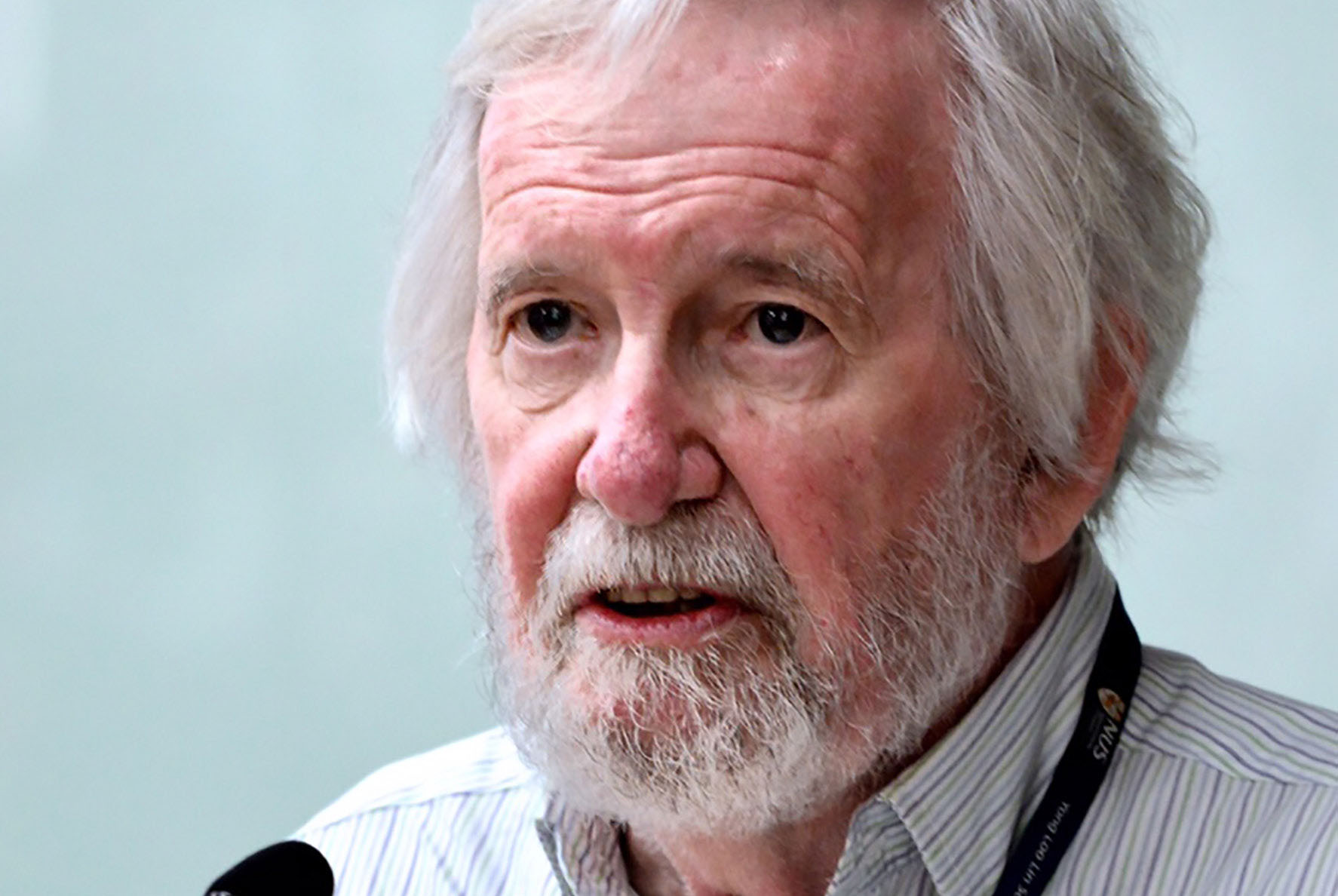

BY PROF ALASTAIR CAMPBELL, CENTRE FOR BIOMEDICAL ETHICS

In Doctored: The Disillusionment of an American Physician, Dr Sandeep Jauhar writes:

“Most of us went into their medicine to help people, not to follow corporate directives or to maximise income. We want to practice medicine the right way, but too many forces today are propelling us away from the bench or the bedside.”

Jauhar’s sense of betrayal and personal failure is common among many doctors today. They embarked on the practice of medicine full of high ideals, choosing it as a career, not just for prestige and a good income, but because they wanted

to help people in their time of need, to make a difference in patients’ lives, as they battle with illness or disability. But the disillusionment comes early on, as shown by many studies of medical students – as the joke puts it, they progress, not from preclinical to clinical phases of study, but from pre-cynical to cynical! Their youthful idealism fades as they encounter the realities of medical practice today and work with some senior doctors who seem to be interested only in money and personal fame, not in the health of their patients.

So what has gone wrong? – and can we fix it? The ancient story of Faust’s pact with the devil seems to capture my concern about what has happened to modern medicine. Faust is a scholar who is depressed and bored with his life, and so he sells his soul to Mephistopheles, the devil’s emissary, in return for 24 years of riches and pleasure. In one version of the tale (to be found in Dr Faustus by Christopher Marlowe) the pact with the devil has its inevitable end, and Faust is cast into hell; other versions (for example, Faust by J. W. von Goethe) have

a happier ending – thanks to the pleading of an innocent woman who was seduced by Faust, God pardons him, despite his numerous sins. So has modern medicine made a Faustian pact, has it sold its soul? And, if so, can it still be redeemed?

WHAT MONEY CAN’T BUY

In What Money Can’t Buy, the Harvard philosopher, Michael Sandel, argues that there have to be moral limits to markets, if we are to preserve those things we value in, and for, themselves. So, if we try to commodify health, education, personal relationships, or acts of kindness to strangers, we destroy their essential nature – we corrupt them to a point when they no longer have real value. Instead they become mere trade-ables in a market, where selfinterest rules, the rich get richer and the vulnerable are exploited for commercial gain. Such commodification is corrupting health care. I shall take two examples – the domination of health care provision by massive transnational financial interests; and the perverse incentives in some methods of delivering heal

th care, which maximise

income at the cost of adequate patient care. But first, we need to recognise the central point: the market alone cannot ensure justice and fairness in health care provision.

they desperately need practitioners they can trust completely. They need objectivity and professionalism from their health care providers; and they need to know that what is being offered to them is done on the basis of need and effectiveness, not as a means to profit the provider, or to balance the books.

Thirdly, the laws of supply and demand do not work in health care, since it is always possible to identify more and more needs in order to create a greater demand. As medicine progressed dramatically over the 20th and 21st centuries, it stimulated more and more demand. People are living longer, but as a result there is a rising tide of chronic illness. At the same time, more and more human problems become medicalised (shyness, for example), stimulating a fresh demand for pharmaceutical or other medical solutions (‘a pill for every ill’). It follows that the market for health care (unlike, say, the market for smart phones) is not self-limiting In the escalating demand for health care the market can guarantee satisfaction – if at all – to only the most wealthy consumers. This limitless demand escalates the costs of health care, creating shortages of even the most basic services for the less well off.

We can now see two examples of how the market in healthcare prevents the fair and effective distribution of resources.

INDUSTRY CAPTURE

The massive growth of the pharmaceutical and medical devices industries over the past few decades has led to a catastrophic undermining of the medical profession’s independence and objectivity. This is well documented in many publications by medical authors who have the knowledge and authority to describe the situation from the inside. Two authors are former editors of one of the top medical journals, The New England Journal of Medicine (see The Truth about Drug Companies by Marcia Angell, and On the Take by Jerome Kassirer); and a recently published book is authored by a senior research fellow in the highly respected Oxford University Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (see Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre). The extent of the industry’s influence on medical practice, on prescribing, and on publication is fully documented in these books and in many other articles.

Here are the main features: a) Publication Bias. The industry ensures that the clinical trials they sponsor are published only if there is a supportive result and, if there is not, they either supress publication, or ‘spin’ the article in a more favourable way. This means that there is a huge disparity between findings published under their auspices and independent studies. Thus clinical decisions are being made every day on insufficient or biased evidence. b) Sponsored educational events. These are the main ways in which postgraduate education is provided and in which clinicians are kept up to date on new developments. Some of the influence is subtle, some more obvious, for example, senior medical figures are paid to give favourable accounts of a specific product. The total amount paid to doctors and health care institutions in the USA can now be discovered, thanks to a clause in the 2010 Affordable Care Act, known as the Sunshine Act. In 2014 it amounted to a staggering US$6.49 billion! c) Ghost writing. Articles are published in high impact journals, with a distinguished list of authors, but in fact the paper has been ghost written by a person employed by the industry. d) Study Design Trials are sponsored to promote a product, with a design almost guaranteed to gain a favourable result.

In addition to these problems, there is increasing evidence that the industry is influencing both the publication policy of journals and the decisions of regulating authorities, such as the FDA. Cancer drugs are a powerful case in point. An article in this year’s British Medical Journal (BMJ) revealed that trials for cancer drugs were 2.8 times more likely not to be randomised than other trials; and only 42% of the 72 drugs approved by the FDA from 2002 to 2014 for solid tumours met the criteria set by the American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Research Committee for meaningful results for patients. Moreover, the median gains in progression-free survival for these drugs were only 2.5 and 2.1 months respectively (see BMJ 2015;350;h2068).

Another example of industry capture is the growth of health maintenance organisations (HMOs), which can incentivise doctors to provide less than the standard of care required for patients, while at the same time squeezing the fees they can charge. This in turn leads to perverse incentives to increase income by adding more and more tests and

treatments, as discussed in the next section.

Such a clear picture of industry capture does seem to prove the point that medicine has sold its soul to commercial interests, maybe for some personal gain for some doctors, but (ironically) to the detriment of the profession as a whole, since they are no longer masters in their own house.

PERVERSE INCENTIVES

A financial incentive is ‘perverse’ when it leads to encouraging practice, which is the opposite of what needs to be achieved in order to deliver effective and equitable care. Some health systems have such incentives built into them. For example, if doctors are allowed to both prescribe and dispense medicines and if they get only a small fee for consultations, then they are incentivised to over-prescribe in order to make an adequate living. The result is the current major problem of antibiotic resistance. Another perverse incentive comes from some fee-for-service systems, since the more tests that are ordered and the more referrals that are made, the higher will be the earnings both of individual practitioners and the institutions in which they work. (In Doctored Sandeep Jauhar describes one patient who was admitted for shortness of breath, and being seen by 17 specialists!) A third perverse incentive comes from the growth of medical litigation. As patients become more prone to sue, doctors are incentivised to order more and more tests and procedures to cover every eventuality (this could be part of the reason for the 17 consultations mentioned above). This leads to what has been called ‘defensive medicine’. A fourth incentive comes from provider

induced needs. These are created in several ways, but one common one is to provide ‘health screening’ aimed to raise anxieties in otherwise healthy people, so that they feel the need to purchase unnecessary treatments or unmerited further investigations.

All of these factors have led to drastically escalating health care costs, but without the benefits to patients we might expect from such expenditure. The American health care scene provides a prime example of this, since it has the highest per capita health expenditure in the world, but is well down the ranking in terms of health outcomes. However, the problem is evident in many other countries also, where the illusion that ‘market forces’ will bring both efficiency and justice has gained acceptance from those funding or managing the health system.

We can recall that one version of the Faust story results in him regaining his soul, thanks to the grace of God. But we cannot expect a divine solution to medicine’s surrender of its soul! If the erosion of professional values in the profession is to be stopped, or even reversed, then the change must come from within the profession itself. How might things change? We need to change both individuals and systems. As regards individuals, much more needs to be done to prevent the slide into cynicism, and this must start when doctors and other health professionals begin their education, and must continue throughout postgraduate training. This is costly on human resources, since the loss of idealism can be reversed only by committed and personalised mentoring. There are many committed senior

practitioners who have not abandoned their ethical dedication, and who can act as role models for the younger generation. A very good example can be found in the lessons learned by the late Dr Richard Teo, a medical practitioner who was enticed by the material rewards of private practice and thought of himself as happy and successful, but then sadly discovered that he was soon to die of terminal cancer.

He then realised that his life had become meaningless, because he had abandoned his professional ideals (sold his soul, if you like). This is all conveyed movingly in a lecture he gave before his death. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umLkfADe17s

‘Follow the money!’ In other words, unless we radically alter the financial incentives and re-apportion the funding to meet the truly vital health priorities of adequate primary care and effective health promotion and disease prevention, the system will never change sufficiently to meet this massive challenge. Good will never be enough, and practitioners will continue to experience burn out and loss of ideals, as they see their efforts undermined by the pursuit of profit.

A DREAM SCHEME

What then should we hope for, if medicine is to ‘save its soul’? Let me suggest four key values that need to be incorporated in a genuinely ethical health care scheme:

Honesty. The scandal of publication bias must be stopped, so that clinical decisions are made on reliable research evidence. There are signs that this is happening, despite lobbying against it by the industry. The European Medicines Agency is now insisting on full access to the clinical research reports on which their decisions are based. This means that independent researchers can check the accuracy of the claims being made by the providers of products. At the same time two organisations – PloS (Public Library of Science) and AllTrials – are pushing for open access and complete publication of trial results (whether favourable or unfavourable to the product). So, every health practitioner needs to ask herself or himself, Am I making clinical decisions on complete and unbiased evidence? And every clinical researcher must ask the key question – will my findings ever see the light of day if I get the ‘wrong’ answer? We need honesty at both individual and institutional level to extract ourselves from the current ethical morass in clinical research findings.

Empowerment. We cannot, of course, isolate medicine completely from the health care industry, and there is no denying the amazing successes in health gains and the eradication of diseases it has achieved. But the balance of power is skewed in the wrong direction. The industry should serve the professions and the public, not be allowed to manipulate the situation to meet its own ends. The professions need to face up to the fact that major aspects of their on-going education, plus virtually all of their specialist conferences, are heavily indebted to the industry. Who then calls the tune? Clearly governments also have a part to play here, since (unlike the health care industries) they are answerable, not to shareholders, but to the public who elected them. Thus it is not sufficient to see such industries as simply good for the economy, if some of their activities are clearly detrimental to health. Here it becomes essential to make sure that regulation of these industries and their products is genuinely independent.

Autonomy. Self-determination or autonomy is an essential value for both health care professionals and patients. The ideal clinical encounter is a partnership between patient and professional, each with a role to play to ensure genuinely patient-centred care. A key factor in this (in addition to the honesty discussed above) is time. If the health care system prevents adequate time for the clinical encounter (or enables it only for the paying patient), then all there can be is a quick solution (often of a pharmaceutical kind) and no opportunity to help patients take responsibility for their own health, to exercise their autonomy and direct their own lives.

Justice. Since health is not a commodity, but a human personal achievement valuable in

itself, every patient should be enabled to develop a capacity for health, according to their needs, not their ability to pay. Of course, people may squander that capacity; they may refuse to take responsibility for actions that undermine their health, and so frustrate the efforts of professionals to help them. But that offer of help, that fostering of capacity, should have nothing to do with the wealth or poverty of the patient. It should be equally available to everyone in need, with the richer patients able to purchase more ‘hotel’ facilities, like private rooms and more elegant surroundings, but not a higher standard of medical care. Equally justice in health care requires that payments for professional services are aligned with major health care needs. Given a rapidly ageing population, this means that efficiency and effectiveness in primary care, prevention and chronic disease management should be adequately rewarded.

Conclusion – Apathy or Hope?

As I noted earlier, whether medicine regains its soul is not something that can depend on a deus ex machina – a divine offer of salvation. No, it is up to us, patients and practitioners alike, to refuse to give up hope of a more ethical system than we have now, and to work to make things change. The motto of King Edward VII Hall (that has nurtured many NUS medical students) is based on a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson, Ulysses. The motto reads ‘to strive, to seek, to serve’. But in Tennyson’s poem, there is even greater resolve:

To strive, to seek, to find

And not to yield.

To save the soul of medicine, it seems we must have such resolve!