A study on the usefulness of high fidelity patient simulation in undergraduate medical education

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2018, 3(1), 42-49

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-1/SC1059

Bikramjit Pal, M. V. Kumar, Htoo Htoo Kyaw Soe, Sudipta Pal

Melaka Manipal Medical College, Manipal University, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: Simulation is the imitation of the operation of a real-world process or system over time. Innovative simulation training solutions are now being used to train medical professionals in an attempt to reduce the number of safety concerns that have adverse effects on the patients.

Objectives: (a) To determine its usefulness as a teaching or learning tool for management of surgical emergencies, both in the short term and medium term by students’ perception. (b) To plan future teaching methodology regarding hi-fidelity simulation based on the study outcomes and re-assessment of the current training modules.

Methods: Quasi-experimental time series design with pretest-posttest interventional study. Quantitative data was analysed in terms of Mean, Standard Deviation and standard error of Mean. Statistical tests of significance like Repeated Measure of Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used for comparisons. P value < 0.001 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results: The students opined that the simulated sessions on high fidelity simulators had encouraged their active participation which was appropriate to their current level of learning. It helped them to think fast and the training sessions resembled a real life situation. The study showed that learning had progressively improved with each session of simulation with corresponding decrease in stress.

Conclusion: Implementation of high fidelity simulation based learning in our Institute had been perceived favourably by a large number of students in enhancing their knowledge over time in management of trauma and surgical emergencies.

Keywords: High fidelity simulation, Simulation in medical education, Stress in simulation

I. INTRODUCTION

High fidelity simulation is an innovative and effective strategy to address increasing student enrolment, faculty shortages, and limited clinical sites (Schoenig, Sittner, & Todd, 2006). The value of simulation in undergraduate medical education is now well established; it basically animates the curriculum. Medical training in the current era is multi-modular and simulation based learning may play a pivotal role in improving training standards in medical schools (Joseph et al., 2015). High Fidelity Patient Simulators replicate patient care scenarios in a realistic environment and have advantage of repetition of the same scenario in a controlled environment which allows practice without risk to patient thereby minimizing chances of medical error and thus, make them a useful tool for student assessment. It is also recognized that putting the learners into a simulated critical care environment subjects them to stresses which have not been well studied. There were many studies on the use of simulation (mainly low and medium fidelity) in medical education but few studies were done on the effectiveness of high fidelity simulation based teaching in under-graduate medical students. The importance of simulation in training medical students are being recognized by academic institutions around the world. In spite of proven benefits, it has so far not been formally introduced as a part of curriculum in medical colleges in our settings. With this background, this study was conducted to explore the perception of medical students on the usefulness of high fidelity patient simulation.

II. METHODS

This was an ongoing research study about the impact of high fidelity patient simulation in undergraduate medical education. METIman Pre-Hospital High Fidelity Patient Simulator (Serial number: MMP-0418/2013; CAE Healthcare, USA) was used in this study. The final year MBBS students of MMMC were the subjects of this study. The students of these batches who volunteered were recruited during their surgical posting after obtaining their informed consent. The proportion of students who volunteered was 92.73% (204 students out of total number of 220 students).

The simulation sessions were conducted with one sub-group of 12 to 15 students which were further divided into 3 teams of 4 to 5 students. The participants were briefed about the simulation sessions and expected learning outcomes. The duration of each simulation session was 50 minutes: Briefing (10 minutes), Simulation (25 minutes) and Debriefing (15 minutes). A theoretical briefing was given by the investigator on ATLS protocol for trauma management and management of surgical emergencies like hypovolemic shock, tension pneumothorax and head injury. This briefing was done as an interactive lecture to the whole subgroup. Each team then participated in a trauma simulation session and the scenario was chosen randomly from among the conditions mentioned above. The three teams in a subgroup were assigned three different scenarios. The teams were then debriefed in order to achieve the learning outcomes. The same team had participated second time in the simulation of the same scenario after 1 week and third time after 3 – 4 weeks to test their short to medium term retention of knowledge and practical skills, followed by final debriefing. Thus, at the end of the course, each student was expected to perform satisfactorily any of the roles during the management of the standard scenarios.

Each student was assessed individually in terms of their progress in knowledge, confidence and stress reduction. We developed a standardized five point (very poor to excellent) Likert scale questionnaire (Appendix I), to collect initial background knowledge of the students on the first day of the training course in terms of ATLS protocol for management of acute trauma, management of hypovolemic shock, management of tension pneumothorax and management of head injury. The same questionnaire was repeated after every session for post-session knowledge assessment.

Another set of five point Likert scale questionnaire was designed to obtain participant feedback after each session on the relevance and usefulness of the simulation experience, effectiveness of briefing and debriefing and stressor assessment. It was an ordinal scale used by respondents to rate the degree to which they agree or disagree to a statement (Appendix II). The stressor questionnaire contained thirteen items (Appendix III). They resembled pre and post tests for comparison to note progress in confidence and stress reduction. Finally, a third set of questionnaire was administered to the students at the completion of training for their feedback assessment of training course (Appendix IV).

We used Microsoft Excel for data entry and SPSS software (SPSS Inc. Released 2009. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc.) for data analysis. We calculated descriptive statistics such as frequency and percentage for categorical data; mean and standard deviation for total score of knowledge, simulation assessment and stressor assessment. We used one-way repeated measure ANOVA to determine the statistically significant difference in simulation assessment (total score) and stressor assessment (total score). We also used Friedman test to determine the statistically significant difference in individual item of knowledge assessment, simulation assessment and stressor assessment. P value <0.001 was taken to be statistically significant in our study.

III. RESULTS

The cohort of 204 participants in this study were selected from four batches of final year MBBS students (October 2015 to April 2016).

Friedman test of simulation assessment for individual items showed significant difference of simulation assessment over time. One-way repeated measure ANOVA of stressor assessment (total score) revealed statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) of total score of stressor assessment over time. Total score of stressor assessment was decreased from 27.09 (Mean) / 7.41(SD) at pre-simulation to 25.63 (Mean) / 8.06(SD) at post-simulation I, to 23.92 (Mean) / 8.92(SD) at post-simulation II and to 23.75 (Mean) / 9.77(SD) at post-simulation III.

For assessment of stress during simulation sessions, we used Likert scale of 1 to 5 (low stress to maximum stress). There was significant difference (p < 0.001) of stressor assessment during simulation over time (Friedman test) for following individual items where majority of the students had the opinion of “moderate stress” regarding “Competition with team members”, “Limited time during simulation sessions”, “Participation in debriefing” and “high stress” regarding “Death of simulated patient”.

|

Item

|

Pre | Post I | Post II | Post III | P value |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | |||||

| 1 – strongly disagree, 2- tend to disagree, 3 – neither agree or disagree, 4 – tend to agree, 5 – strongly agree | |||||

| The session level was appropriate to my present level of knowledge and experience | 4.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | <0.001* |

| It encouraged my active participation | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | <0.001* |

| Clinical management more easily learned | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 0.996 |

| The training session resembled a real life situation | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 0.011* |

| It helps me to think quickly | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 0.003* |

| Repetition of the scenario during training is essential | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 0.001* |

| Time for the scenario was adequate | – | 4.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 0.149 |

| Briefing and Debriefing: | |||||

| Time for initial briefing was adequate | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | <0.001* |

| Time for debriefing was adequate | – | 4.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 0.184 |

| Debriefing helped me to learn better | – | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 4.0) | 0.273 |

| Affective: | |||||

| I want to have further sessions on the simulator | – | 5.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | <0.001* |

| I feel that simulation is essential to train in trauma management | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | 5.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (4.0, 5.0) | <0.001* |

| Learning Outcomes: | |||||

| I am confident of managing a trauma scenario in real life | – | 3.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 4.0) | <0.001* |

Table 1. Simulation assessment at pre-simulation, post-simulation I, post-simulation II and post-simulation III (individual item)

IV. DISCUSSION

High fidelity simulators have revolutionised training as almost any emergency situation can be replicated. Simulation sessions have provided opportunity for clinical students to collaborate and apply both cognitive and psychomotor skills. Our main objective was to determine usefulness of high fidelity simulation as a teaching or learning tool for management of surgical emergencies. The study showed that high fidelity simulators had made a difference in enhancing the knowledge over time in management of trauma and surgical emergencies as perceived by our students. It also showed that learning had significantly improved with each session of simulation and learners’ attitudes were supportive of simulation. Wayne, Barsuk, O’Leary, Fudala, & McGaghie (2008) showed that internal medicine residents had increased knowledge and skills using simulation technology and deliberate practice. Participants in one study (Okuda et al., 2009) felt simulation based teaching was a reliable tool for assessing learners by providing good feedback on performance which was similar to our observation. In a study by Founds, Zewe, & Scheuer (2011), participants felt that high fidelity simulators can present simulations that were closer to real life situations which was similar to opinion of most of our students. The study revealed that simulation sessions with high fidelity simulators encouraged active participation of students who need further sessions on simulation for better understanding of clinical problems and knowledge acquisition. The finding in one of the main area of study: “Clinical management more easily learned” was not satisfactorily documented (p < 0.996). It showed that simulation did not always help in better understanding of management of clinical problems. The drop in stress was significant at week II and III but flattened out in week IV which might be due to participants’ increasing adaptability to simulated atmosphere. The time for briefing was adequate but participants felt that time for debriefing was inadequate and debriefing did not help them to learn better. This was an area of utmost concern to us as we concluded that there was a definite lacuna in our debriefing process. We planned to rectify our shortcomings and deficiencies in this matter. For long term assessment we planned to get these students back during their internship period and do a re-test to validate the improved outcome. Most of the students had a favourable perception about high fidelity patient simulation indicating that it has bright prospect for its inclusion in under-graduate curriculum in near future.

V. CONCLUSION

Few studies have been done with regards to students’ perception on the effectiveness of high fidelity simulators in training under-graduate medical students. This innovative training method may help to improve the quality of medical care and safety of the patient. The limitation of this study: This was a single centre study and participants who volunteered were only recruited. Hence findings may not be applicable to other settings. Even though training with high fidelity simulators was perceived positively by the students, it remained unclear whether the learning skills acquired with this teaching methodology would translate into improved patient care.

Notes on Contributors

Bikramjit Pal MBBS, DA (Anesthesiology), MS (Surgery); Associate Professor, Department of Surgery and Chairman of Clinical Skills Learning Committee, Member of the International Forum of Teachers of the UNESCO Chair in Bioethics, Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Manipal University, Malaysia

MV Kumar BSc, MBBS, FRCS Ed; Professor and Ex-HOD, Department of Surgery and member of Clinical Skills Learning Committee, Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Manipal University, Malaysia

Htoo Htoo Kyaw Soe MBBS, MPH, PhD; Associate Professor, Department of Community Medicine and member of Statistics Committee, Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Manipal University, Malaysia

Sudipta Pal MBBS, PGDMCH; Lecturer, Department of Community Medicine, Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Manipal University, Malaysia

Ethical Approval

Duly taken from the IRB & IEC, Melaka-Manipal Medical College.

Acknowledgements

The final year MBBS students of Melaka-Manipal Medical College who had participated in this research project, the faculty of the Department of Surgery, the lab assistants and technicians of Clinical Skills Lab, the Management of Melaka-Manipal Medical College and last but not the least, Prof. Dinker Pai (Ex-Head of Department of Surgery, MMMC), for his inspiration, initiation and conceptualization of this research project.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study and have no conflicts of interest.

References

Founds, S. A., Zewe, G., & Scheuer, L. A. (2011). Development of high fidelity simulated clinical experiences for baccalaureate nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 27(1), 5–9.

Joseph, N., Nelliyanil, M., Jindal, S., Utkarsha., Abraham, A.E., Alok, Y., … Lankeshwar, S. (2015). Perception of Simulation based Learning among Medical Students in South India. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, 5(4), 247–252. doi: 10.4103/21419248.

Okuda, Y., Bryson, E. O., De Maria, S. Jr., Jacobson, L., Quinones, J., Shen, B., & Levine, A. l. (2009). The utility of simulation in medical education: What is the evidence? Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 76(4), 330–43. doi: 10.1002/msj.20127.

Schoenig, A. M., Sittner, B. J., & Todd, M. J. (2006). Simulated clinical experience: nursing students’ perceptions and the educators’ role. Nurse Education, 31 (6), 253-8.

Wayne, D. B., Barsuk, J. H., O’Leary, K. J., Fudala, M. J., & McGaghie, W. C. (2008). Mastery Learning of Thoracentesis Skills by Internal Medicine Residents Using Simulation Technology and Deliberate Practice. Society of Hospital Medicine, 3(1), 48-54. doi: 10.1002/jhm.268.

*Bikramjit Pal

Associate Professor (Surgery),

Melaka-Manipal Medical College

Jalan Batu Hampar, Bukit Baru,

75150, Melaka, Malaysia.

Mobile: +60-1118728085.

Landline (Office): +60-6-2896662-1116; +60-6-2925849/50/51.

FAX: +60-6-2817977.

E-mail: bikramjit.pal@manipal.edu.my

Alternative email: drbikramjitpal@gmail.com

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2018, 3(1), 38-41

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-1/SC1040

Sean Wu1, Julia Farquhar1, 2, Scott Compton1

1Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 2School of Medicine, Duke University, USA

Abstract

Aim: Evidence suggests that Team Based Learning (TBL) is an effective teaching method for promoting student learning. Many people have also suggested that TBL supports other complex curriculum objectives, such as teamwork and communication skills. However, there is limited rigorous, substantive data to support these claims. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess medical educators’ perceptions of the outcomes affected by TBL, thereby highlighting the specific areas of TBL in need of research.

Methods: We reviewed the published research on TBL in medical education, and identified 21 unique claims from authors regarding the outcomes of TBL. The claims centred on 4 domains: learning, behaviours, skills, and wellbeing. We created a questionnaire that asked medical educators to rate their support for each claim. The survey was distributed to the medical educators with experience teaching via TBL and who were active users of the Team Based Learning Collaborative listserv.

Results: Fifty responses were received. Respondents strongly supported claims that TBL positively impacts behaviours and skills over traditional, lecture based teaching methods, including the promotion of self-directed learning, active learning, peer-to-peer learning, and teaching. In addition, respondents strongly supported claims that TBL promotes teamwork, collaboration, communication and problem solving. Most participants reported that TBL is more effective in promoting interpersonal, accountability, leadership and teaching skills.

Conclusion: Medical educators that use TBL have favourable perceptions of the practice across a variety of domains. Future research should examine the actual effects of TBL on these domains.

Keywords: Team Based Learning; Medical Education; Teaching

I. INTRODUCTION

Team-based learning (TBL), originally developed for use in business schools, is now a growing teaching modality in medical education. The process of TBL is comprised of three components: advance preparation, individual and team readiness assurance tests (RATs), and in-class application of content through team exercises (Parmelee, Michaelsen, Cook, & Hudes, 2012). In a TBL course, students are typically assigned into teams of 5 to 7, and receive preparatory materials before class. At the beginning of the TBL process, each individual completes a readiness assurance test (I-RAT). Students next re-take the same readiness assurance test during class as a team (T-RAT), reaching consensus to select a single best answer, and receive immediate feedback. Students typically then have the option to write evidence-based appeals for their wrong answers, and finally an instructor clarifies lingering questions. Following the readiness assurance phase, the teams then work on solving applied problems, followed by whole class discussions. Evidence suggests that TBL is a popular teaching modality, with approximately one-third of US schools and colleges of pharmacy implementing it into the curriculum (Allen et al., 2013).

A number of studies have shown TBL to be as academically effective or more effective than traditional lecture-based courses by promoting mastery over several core medical subjects (Fatmi, Hartling, Hiller, Campbell, & Oswald, 2013; Koles, Stolfi, Borges, Nelson, & Parmelee, 2010; Nieder, Parmelee, Stolfie, & Hudes, 2005). These studies have focused specifically on the academic outcomes of TBL, yet TBL as a teaching modality is often assumed to support complex curriculum objectives such as teamwork and communication skills. Despite these assumptions, little substantive data exists to support these claims. For the current body of research to progress and to improve our understanding of the true effects of TBL, these assumed outcomes need to be explicitly described and articulated. Following which, individual outcomes can be studied and interventions can be proposed to further develop TBL as a medical teaching modality. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess TBL medical educators’ perceptions of the outcomes affected by TBL, thereby providing a framework for future research.

II. METHODOLOGY

A. Development of Questionnaire

We identified 21 claims of the positive effects of TBL in various published papers and textbooks. We categorized these claims into 4 domains: learning, behaviours, skills, and well-being. Examples of references to each claim are available from the corresponding offer. We subsequently compiled those claims and used them as the basis for a questionnaire in order to assess the support for each claim among TBL users.

The final questionnaire consisted of 6 demographic questions, followed by the claims within each domain: learning (4 questions), behaviours (4 questions), skills (8 questions) and wellbeing (5 questions). In addition, we asked 3 questions related to the extent that TBL skills learned in classroom settings translates to clinical settings.

Cognitive interviews were conducted with ten TBL educators to determine if the questions were clear and interpreted as intended. Relevant edits were made and the questionnaire was revised. We then assessed reliability using the test-retest method. Eight TBL educators responded to the questionnaire twice within two weeks. The test-retest reliability of the instrument was 0.927 (df = 8, p<0.001) based on Spearman’s correlation coefficient, thus demonstrating its suitability for research use.

B. Dissemination

The final survey was uploaded onto surveymonkey.com and submitted to the Team-Based Learning Collaborative (TBLC) listserv with a request for medical educators to respond. The TBLC listserve is comprised of people interested in TBL, and is open to all educators. The introductory email made explicit that medical educators were the target of the survey.

III. RESULTS

A total of 50 medical educators replied. The participants were a seasoned group of medical educators, having an average of 14 years’ experience in the field. Most respondents were senior faculty members (25% professor, 36% associate professors), while 19% were assistant professors and 20% had other academic appointments. Overall the respondents had substantial experience in using TBL: 96% had created TBL materials, 98% had facilitated TBL discussions, and 78% had designed course curriculum with TBL as the primary educational modality.

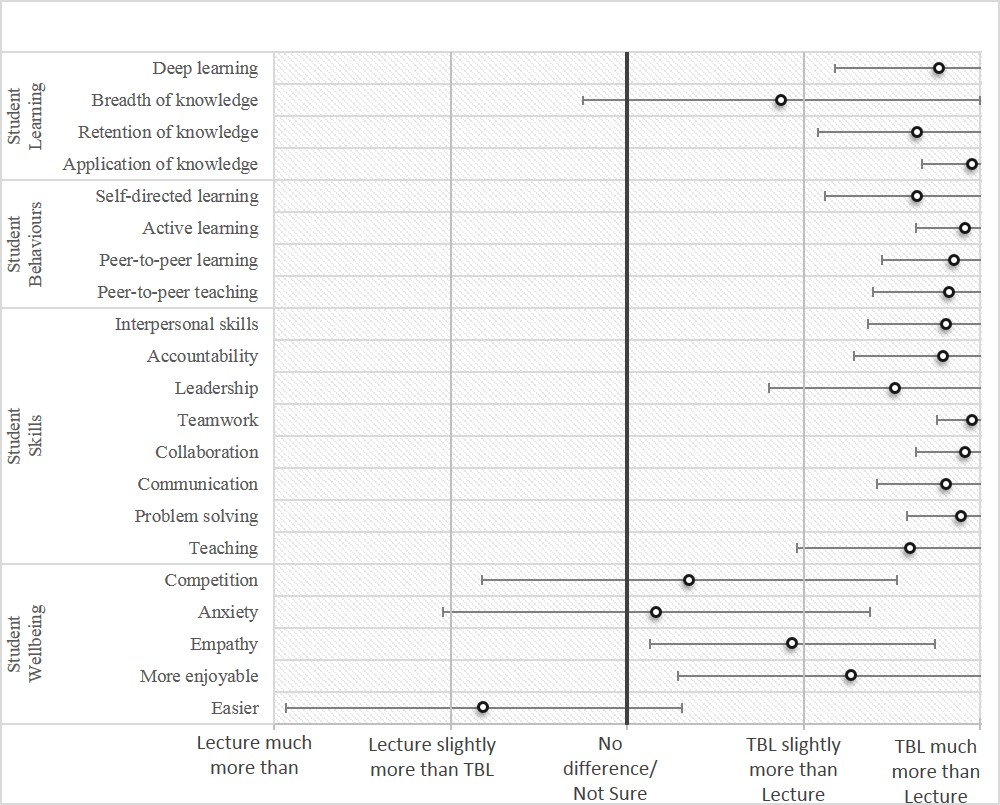

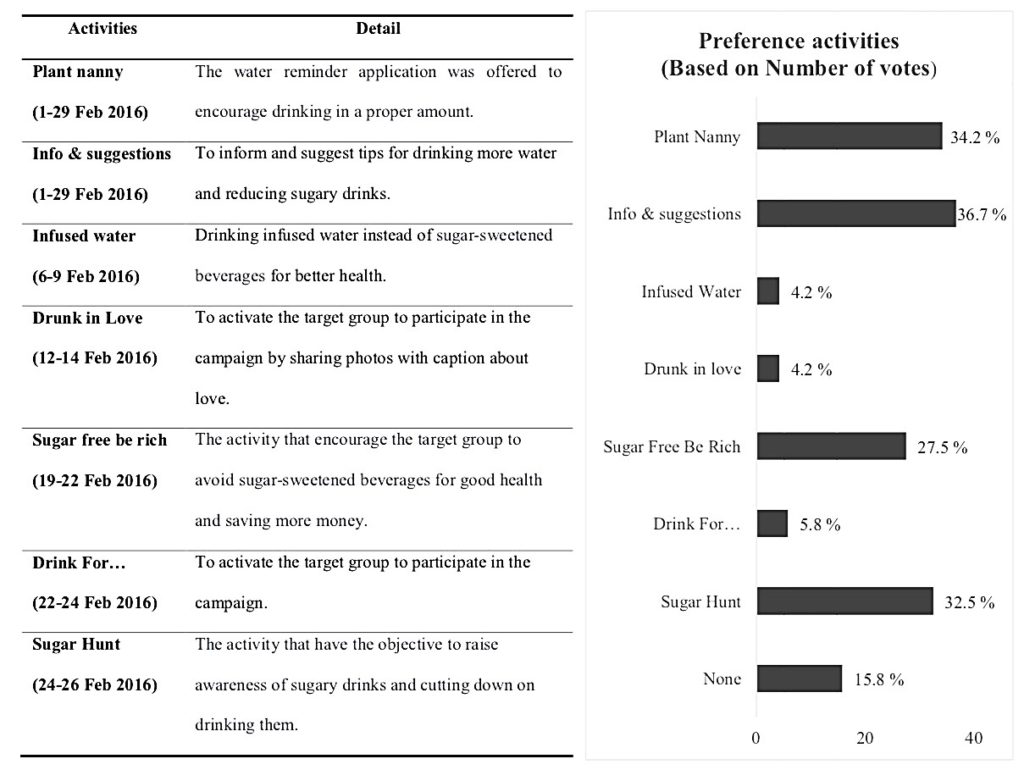

As shown in Figure 1, respondents tended to strongly support the various claims that suggest TBL positively impacts learning, behaviour, and skills. In fact, most participants reported that TBL promotes “Deep Learning” and “Application of knowledge” much more, 83% and 98% respectively, than conventional lecture based modalities. Nearly all (96%) reported that TBL is more effective in promoting retention of knowledge than lecture and most (64.5%) replied that TBL is more effective in promoting breadth of knowledge. A minority (25%) of respondents indicated that there is no difference between the two teaching modalities in student learning.

In terms of student behaviour, respondents reported that TBL promotes self-directed learning, active learning, peer-to-peer learning and teaching much more than lecture based teaching modalities. Most (98%) answered that TBL is more effective in teaching self-directed learning, peer-to-peer learning, and peer-to-peer teaching than lecture. All answered that TBL promotes active learning more than traditional lecture based teaching. Only one replied that TBL and lecture-based teaching are equally effective in promoting the aforementioned student behaviours.

Most respondents replied that TBL is more effective than lecture-based teaching in promoting a multitude of student skills. All answered that TBL is better at promoting teamwork, collaboration, communication and problem solving. Most of participants reported that TBL is more effective in promoting interpersonal, accountability, leadership and teaching skills.

Figure 1 also demonstrates that there is less support for the claims surrounding TBL promotion of wellbeing. Nearly half (44%) of the respondents answered that TBL resulted in more competition than lecture-based teaching whereas a quarter replied the opposite. Half reported that TBL leads to more anxiety whereas a quarter replied otherwise. More than half reported that TBL promoted empathy more so than lecture, whereas 35% of respondents were unsure or thought the two teaching modalities equal. Most respondents answered that lecture-based teaching was easier than TBL, yet also answered that TBL was more enjoyable. Interestingly, respondents also reported that TBL-learned skills translated well to the clinical setting. Most, 89.5%, 83.3%, and 66.7% respectively, answered that teamwork, communication, and leadership skills learned in a TBL classroom were applicable to the clinical rotations.

Figure 1. Medical educators’ ratings: lecture-based teaching versus team based learning in promoting different skills

IV. DISCUSSION

The results of the study indicate that TBL medical educators believe TBL to be better than traditional lecture-based teaching in achieving a vast variety of outcomes. According to the survey results, educators believe that TBL promotes students’ mastery of subject content by encouraging deep and active learning as well as the retention and application of knowledge. They also believe that TBL develops behaviours such as peer-to-peer learning and teaching. An important point is that most TBL educators believe TBL fosters development of key skillsets such as accountability, teamwork, collaboration, and communication that play vital roles in the successful transition of students from classroom learning to clinical clerkships. Yet respondents to this survey may be wary that TBL may negatively affect student wellbeing by increasing competition and difficulty. Interestingly, many of the TBL educators appeared confident that TBL aids in the development of medical students that are independent learners, teamwork-oriented and effective leaders. However, to date, there is little substantive data to suggest that any of these claims are true. Likewise, there was strong support for the notion that skills learnt in classroom TBL sessions translate to the clinical setting. Again, little evidence currently exists to support this claim.

This study is limited by the small convenience sample drawn from the TBL collaborative listserv. The participants may not be representative of TBL educators as a whole. However, the participant profiles reveal that these respondents have extensive experience in medical education and using TBL in the classroom.

V. CONCLUSION

This study should serve as a call to action to educational researchers to investigate the claims of the effects of TBL, particularly those associated with non-academic factors, such as teamwork, leadership, and communication. In fact, the results of this study could serve as the foundation for future research. Ensuing studies can provide evidence towards determining the validity of these assumptions, thereby providing direction for the development of TBL as a teaching modality in medical education.

Notes on Contributors

Sean Wu, MD, is a graduate of the Duke-NUS Medical School and currently an Internal Medicine resident at NUHS. Julia Farquhar is a medical student at the Duke School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

Scott Compton, PhD, is the Associate Dean and Associate Professor of Medical Education, Research, and Evaluation at Duke-NUS Medical School.

Ethical Approval

The approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, National University of Singapore.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Allen, R. E., Copeland. J., Franks, A. S., Karimi, R., McCollum, M., & Riese, D. J. (2013). Team-based learning in US colleges and schools of pharmacy. The American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 77(6). DOI: 10.5688/ajpe776115

Fatmi, M., Hartling, L., Hillier, T., Campbell, S., & Oswald, A.E. (2013). The effectiveness of team-based learning on learning outcomes in health professions education: BEME Guide No. 30. Medical Teacher, 35(12), 1608-24. DOI: 10.31.09/0142159X.2013.849802

Koles, P. G., Stolfi, A., Borges, N. J., Nelson, S., & Parmelee, D.X. (2010). The impact of team-based learning on medical students’ academic performance. Academic Medicine, 85(11), 1739-1745. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f52bed

Nieder, G. L., Parmelee, D. X., Stolfi, A., & Hudes, P. D. (2005). Team‐based learning in a medical gross anatomy and embryology course. Clinical Anatomy, 18(1), 56-63. DOI: 10.1002/ca.20040

Parmelee, D., Michaelsen, L.K., Cook, S., & Hudes, P.D. (2012). Team-based learning: A practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. Medical Teacher, 34(5), e275-e287. DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179

* Scott Compton, PhD

Medical Education, Research and Evaluation Department

Duke-NUS Medical School

8 College Road, Singapore 169857.

Tel: +65 6601 1565.

Email: scott.compton@duke-nus.edu.sg

Published online: 4 September, TAPS 2018, 3(3), 39-42

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-3/SC1057

Lim Mien Choo Ruth, Keith Tsou Yu Kei, Chooi Peng Ong, Sabrina Wong Kay Wye, Gilbert Tan Choon Seng, Winnie Soon Shok Wen, Joanne Quah Hui Min & Marie Stella P. Cruz

Division of Graduate Medical Studies, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore

Abstract

This paper describes the revision of a national post-graduate medical examination to incorporate formal quality assurance and psychometrics. We discuss the considerations and rationale leading to the new format, challenges faced and lessons learned in making the change. The processes described were successfully implemented in the 2015 examination administration. We continue to reflect on and analyse these processes to improve the examination.

Keywords: Post-graduate, Examination Reform, Quality Assurance, Psychometrics, Family Medicine, Standardised Patient

I. CONTEXT

In Singapore, population growth and a swiftly inverting population pyramid have diametrically changed the job scope of the family physician, impacting training and certification.

Postgraduate Family Medicine certification in Singapore formally began with the Membership of the College of General Practitioners (MCGP) in 1972, and was replaced in 1993 by the Master of Medicine in Family Medicine (MMed FM) examination. This examination comprised a theory portion, a viva voce and a clinical examination (Table 1).

In 2011, Singapore adopted the American Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-International (ACGME-I) Residency system. Family Medicine Residency culminates in a summative multiple-choice question (MCQ) examination administered by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) with no clinical component.

With these training and contextual changes, the time was appropriate for a review and revision of the MMed FM examination. We describe the considerations and processes leading to the new MMed FM examination in 2015.

II. FROM THE OLD TO THE NEW

A. Family Medicine Examination Committee

In 2012, the Family Medicine Examination Committee (FMEC) was set up to administer and review the examination, reporting to the Division of Graduate Medical Studies (DGMS), with education consultative support from the Centre for Medical Education, National University of Singapore. Senior family physicians from different training institutions form the FMEC.

B. Reviewing the Old Examination

| Old MMed FM Examination | 2015 MMed FM Examination | Rationale for change | |

| Format | Theory

Essays, Short Answers, MCQ, Slides, Viva voce |

Theory

250 MCQ Paper |

Increased sampling points to increase reliability |

| Clinical Examination

2 Long Cases, 4 Short Cases |

Clinical Examination

Slides, Viva voce, 3 Long Consultations, 5 Short Consultations, 3 Physical Examinations |

Increased sampling points to increase reliability

|

|

| Duration of Clinical Examination | 150 minutes | 218 minutes | Increased testing time |

| Domains Tested | Knowledge – Theory papers, Long Cases

Synthesis, Psychomotor skills – Short Cases Professional Communication – Long Cases, Viva voce

|

Knowledge, Interpretation, Application – Context-rich MCQs

Synthesis, Application, Patient Communication – Consultations Psychomotor skills – Physical Examinations Professional Communication – Viva voce |

Increased number of domains tested

Higher level of cognitive domains tested |

| Blueprinting | Theory

No formal blueprinting |

Theory

Formal blueprinting |

Defined composition of testing points |

| Clinical Examination

Long Cases were “eyeballed” to cover adult and paediatric problems Short Cases blueprinted by broad body systems and “eyeballed” such that a candidate did not have similar Long and Short cases |

Clinical Examination

Formal blueprinting across Consultations and Physical Examination stations |

Defined composition of testing points

|

|

| Clinical Material used | Real Patients (RP) | Real Patients

Standardised Patients (SP) |

Increased number of sampling points

Increased type of testing points Richness of clinical material with use of RP Standardisation of clinical material with use of SP |

| Quality Assurance | Blueprinting | Blueprinting | Increased content validity with new blueprint |

| Examiner training by observation | Formal Examiner Training & Feedback | Systematisation of examiner training | |

| Pre-set Pass Mark | Standard setting methods and psychometrics in Pass/Fail decisions | Better defensibility of Pass/Fail decisions | |

| External Examiner | External Examiner | Independent audit of examination process |

Table 1. Summary of main components of the old and 2015 examinations

The previous long case involved assessing the patient and discussing management with the examiner. The short case was a physical examination station. Two long cases provided insufficient insight into the candidate’s mastery of the breadth of the Family Medicine curriculum (Swanson, Norman, & Linn, 1995). With real patients, standardisation of testing points across a cohort was not possible. Management was discussed with the examiner only, so communication with the patient about management was not assessed.

The old pass mark was pre-defined at 50%, regardless of difficulty of cases.

C. Developing the New Examination

We developed the new examination following review of literature (Swanson, Norman, & Linn, 1995; Van der Vleuten & Schuwirth, 2005; Mookherjee, Chang, Boscardin, & Hauer, 2013) and discussion to determine best practice. Our priorities were to improve the representativeness and reliability of testing within a practicable framework.

The new examination includes theory and clinical components, and psychometrics to analyse candidate performance. The theory component is now the ABMS MCQ examination. Candidates who are successful may sit the clinical examination.

The re-designed clinical examination comprises thirteen stations, with the slides and viva voce stations being holdovers from the old format. The remaining eleven comprise five short consultations, three long consultations, and three physical examination stations, an increase over the previous six stations (Swanson et al, 1995). This increases the number of sampling points and testing time and hence reliability (Van der Vleuten & Schuwirth, 2005).

For the consultations, the candidate evaluates, and then discusses management with the patient. He is judged on his handling of the consultation, not on his interaction with examiners. A long consultation tests multiple and more complex issues than a short consultation. Consultations are set in a primary care context, representing Family Medicine practice in Singapore.

The standardised patient (SP) was introduced, and consultations involve real and standardised patients. The three physical examination stations continue to use real patients.

The viva voce was retained to allow testing of professional communication and discussion of clinical reasoning.

Instead of a pre-defined standard, we introduced the use of psychometrics to determine the pass marks, and collaborated with a medical educationist who has been trained in assessment psychometrics. At the same time, we implemented examiner training (Van der Vleuten, Luyk, Ballegooijen, & Swanson, 1989), calibration, and standard setting. The passing standard is defined as that of a proficient family physician on the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition (Goh & Ong, 2014).

A new mark sheet, assessing clinical skills and global assessment of the candidate’s performance, was introduced.

D. Evaluating the New Examination

The FMEC committed to incorporating quality assurance measures into the design and implementation of the new clinical examination.

For the first time, an examination blueprint was formally developed. Testing points were chosen across the curriculum to reflect competencies required in Family Medicine practice (Mookherjee et al, 2013).

The blueprint guided recruitment of real patients and SP case development. FMEC members tested the SP cases for authenticity and reasonableness. Before each clinical examination bloc, all examiners participated in calibration sessions during which clinical history and signs were confirmed and salient points agreed upon.

Borderline regression and modified Angoff methods were used to set pass marks. Performance and reliability of individual stations and the entire examination were studied. Examiner performance was analysed and feedback given.

The examination, conducted under the auspices of the DGMS, conformed to standard operating procedures, access and security measures used in other DGMS examinations.

An external examiner (EE) observed the examination (Associate Professor Neil Spike). This EE had observed previous MMed FM examinations.

III. CHALLENGES AND LESSONS

The old examination format had been in place for forty-three years (1972 – 2014). The new format introduced standard setting, examination validity as an evidence-based concept, the use of SPs, and the use of statistics to analyse results.

Stakeholder engagement was, and remains, paramount. There was a need for consistent, sustained communication to trainers, residents and examiners.

With the consultation as test encounter, we are assessing for relevant history and hypothesis-driven physical examination. This differs from traditional assessment that rewards comprehensiveness. Examiners debated the boundaries of relevance and hypothesis-driven practice, to help form their expert judgement of what is required of proficiency.

With the many changes introduced, we set a requirement for examiners to have attended examiner training sessions before appointment. This is common in many examinations but new to us.

The format, as presented here, will remain for 2016 and 2017, after which time we will review the programme of assessment. At this time, we are in the process of gathering feedback and reviewing the outcomes for the examination administrations of 2015 and 2016.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Ruth Lim is the Chairperson of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Chief Examiner for the Master of Medicine (Family Medicine) Examination and Director of Education for SingHealth Polyclinics.

Dr Keith Tsou is the Deputy Chairperson of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Deputy Chief Examiner for the Master of Medicine (Family Medicine) Examination and Director of Clinical Services for National University Polyclinics.

Dr Ong Chooi Peng is member of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Senior Consultant of the Department of Family Medicine, National University Health System.

Dr Sabrina Wong is member of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Assistant Director of Clinical Services for National Healthcare Group Polyclinics.

Dr Gilbert Tan is member of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Assistant Director of Clinical Services for SingHealth Polyclinics.

Dr Winnie Soon is member of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Consultant Family Physician for National Healthcare Group Polyclinics.

Dr Joanne Quah is member of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Director for Outram Polyclinics under SingHealth Polyclinics.

Dr Marie Stella P. Cruz is member of the Family Medicine Examination committee, Family Physician and Adjunct Lecturer for Department of Medicine and Division of Graduate Medical Studies, National University of Singapore.

Ethical Approval

No IRB approval is involved.

Declaration of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Swanson, D. B., Norman, G. R., & Linn, R. L. (1995). Performance-based assessment: Lessons from the health professions. Educational Research, 24(5), 5-11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X024005005.

Van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Schuwirth, L. W. T. (2005). Assessing professional competence: from methods to programmes. Medical Education, 39, 309-17. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02094.x.

Vleuten, C. V., Luyk, S. V., Ballegooijen, A. V. & Swanson, D. B. (1989). Training and experience of examiners. Medical Education, 23(3), 290-6.

Goh, L. G. & Ong, C. P. (2014). Education and training in family medicine: progress and a proposed national vision for 2030. Singapore Medical Journal, 55(3), 117-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2014031.

Mookherjee, S., Chang, A., Boscardin, C. K. & Hauer, K. E. (2013). How to develop a competency-based examination blueprint for longitudinal standardized patient clinical skills assessments. Medical Teacher, 35(11), 883-90. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.809408.

*Ruth Lim

Division of Graduate Medical Studies,

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine,

National University of Singapore

Blk MD3, Level 2, 16 Medical Drive,

Singapore 117600

Email: ruth.lim@singhealth.com.sg

Contact: +65-63777018

Published online: 4 September, TAPS 2018, 3(3), 35-38

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-3/SC1062

Li-Phing Clarice Wee

Ng Teng Fong General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Objectives: Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) orders have been used in hospitals worldwide for the past 30 years, but are still considered to be a challenging and difficult area of practice. Nurses being the frontline healthcare professionals should be involved during the decision-making process and are required to have good understanding of the DNAR order, in order to provide effective and efficient care. Our aim was to investigate: nurses’ involvement during decision-making process, level of understanding of issues surrounding DNAR orders; and how they perceive care for patients with DNAR orders.

Methods: A descriptive crossed sectional study design using electronic questionnaires was adopted for the study. The study was conducted among 400 nurses at a tertiary hospital in Singapore.

Results: This study showed that 44.5% of nurses reported physicians did not involve them in decisions for DNAR orders; only 8% felt that they should be involved in the decision-making process. Even if they did not agree with the order, 63.2% would still comply whilst 21% of them were willing to discuss this further with the treatment teams. Most agreed that antibiotics, intravenous fluids, oxygen therapy and artificial feeding were appropriate for patients with DNAR orders. Majority (57.1%) expressed uneasiness in discussing end of life issues with patients even in specialty areas.

Conclusion: Nurses should be encouraged to advocate for their patient and take part in the decision-making process. Communication between the medical team and nurses can be improved and there is an obvious need for further improvement in education and collaboration in this area.

Keywords: Do Not Attempt resuscitation, End-of-Life, Withdrawal, Palliative Care

I. INTRODUCTION

Do-Not-Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) orders have been used in hospitals worldwide for over the past 30 years with the intention of preventing non-beneficial treatments for hospitalized patients. These orders provide direction for the medical team and often take place after discussion with the patient, their family members and the multidisciplinary team as this decision is often complex with possible legal, ethical and moral implications. Although these decisions are typically initiated by physicians, nurses play a key role in DNAR discussions as well (Gendt et al., 2006).

Nurses are often the first point of contact for a patient and have the responsibility to act as patient advocates (Fitz, Fuld, Haydock & Palmer, 2010). They are in the best position to fulfil a liaison role between physicians and patients; conveying patient preferences to the physicians and influencing acceptance by the patient or surrogate decision-maker of the medical recommendations of DNAR (Gendt et. al, 2006). Many studies have shown that healthcare workers tend to provide less medical care to DNAR patients and inconsistencies around what continuing care should be given to patients exist. Similarly, DNAR orders can also influence the delivery of nursing care. Fitz et. al (2010)’s study showed that a significant number of nurses believed a DNAR order altered nursing observation frequency, pain relief and fluids administered.

Though end-of-life care and patients with DNAR orders can co-exist, there might be a fine line in terms of treatment goals and outcomes. A study done by Stewart and Baldry (2010) found that a DNAR decision is perceived by some as equivalent to withdrawal of active treatment. The aim of the study was to identify nurses’ involvement during the decision-making process, level of understanding of issues surrounding DNAR orders; and how they perceive care for patients with DNAR orders.

II. METHODS

A. Design and Setting

A descriptive crossed sectional study design using electronic questionnaires was adopted for the study. It was conducted at 700-bedded hospital in Singapore where approximately 2500 nurses work full-time.

B. Sample

Convenience sampling method was adopted for the recruitment of nurses in the study and 400 nurses participated in the study.

C. Instruments Used

The questionnaire was adapted from a previous study with the author’s permission (O’Hanlon, O’Connor, S., Peters & O’Connor, M., 2013) and piloted on 50 nurses working in the ICU and High Dependency Unit (HDU). Thereafter, the questionnaire was further modified and consisted of 24 questions to improve the clarity of some questions and to better address the aims of the study.

D. Data Collection and Analysis

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board prior to data collection. Data was collected over a period of 5 months (June – October 2016). Consent was assumed if the survey was completed. Responses were collected anonymously through an electronic platform with a secured login. Responses were confidential and descriptive statistics analysis was used to analyse the data.

III. RESULTS

Majority of respondents were 21-30 years old females, with an average work experience of less than 5 years. Most of the participants were Chinese and an equal number of participants had a degree or Masters as their highest qualification. Majority of the participants were staff nurses who work in a medical ward, whilst other responses were collected from nurses working in the ICU, emergency department (ED) and surgical wards.

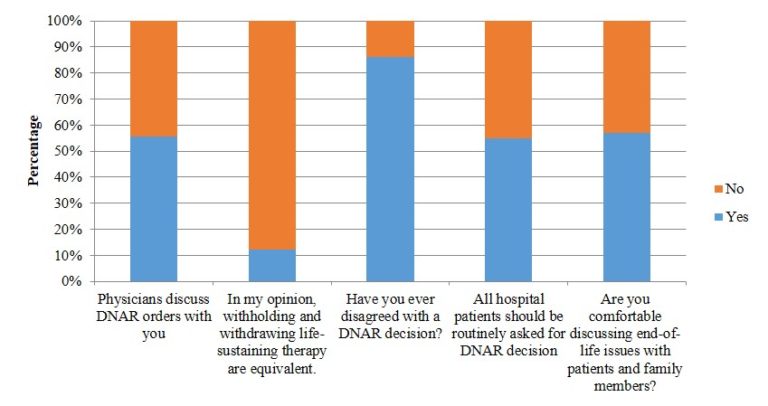

A. Involvement in the Decision-Making Process

Nurses thought that the patient (75.5%), family members (83.5%) and physicians (79%) should be involved in DNAR decision-making process as shown in Figure 1. However, only 8% thought that nurses should be involved in this process. A proportion of nurses (13.8%) reported that they had previously disagreed with a DNAR decision, but 63.2% said that they would still comply with the orders even if they did not agree. Majority (57.1%) of the nurses reported that they were not comfortable discussing end-of-life issues with patients and their family members and a sub-group analysis revealed that this was also true for nurses working in specialty areas like the Intensive Care Unit, High Dependency Unit and Emergency Department.

Figure 1. Involvement in the decision-making process (N=400)

B. Perceptions and Understanding

The results in Figure 1 showed that majority (63%) felt that withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining therapy were equivalent. There was no consensus with regards to the survival rate for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and in-hospital cardiac arrest rates and these were generally overestimated. If a patient had a DNAR order in place, therapies like antibiotics, intravenous fluids, oxygen therapy and nasogastric feeds were deemed to be appropriate. Other therapies like intubation, cardiac compression, defibrillation, surgery, transfer to HD or ICU, dialysis and antiarrhythmic for life threatening cardiac rhythm were thought to be less appropriate. There were no differences observed between junior and senior nurses.

IV. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate nurses’ involvement during the decision-making process; and how they perceive care for patients with DNAR orders in a Singapore.

The study provided insight to gaps in communication that exist amongst the medical and nursing team; and the central importance of communication between these two teams. From the study, an alarming number of nurses revealed that they were not comfortable discussing end-of-life issues with patients or family members, even if they worked in critical areas.

Unlike Western countries, Singapore does not have a national policy on DNAR or an established framework to guide end-of-life care. Various studies have reported that the distinction between withholding and withdrawing treatment is not always recognised, and an assumption is often made that DNAR equates to withdrawal of active treatment (Stewart & Baldry, 2010). This is also observed in this study as majority of the respondents felt that withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining measures were equivalent. There is often an overlap between the two areas but more importantly, these decisions should be individualised to patients.

Results of the study showed that respondents of this study generally overestimated the survival rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest rates, in-hospital survival rates, recovery with good neurological function and survival to discharge. This study also revealed that nurses regarded therapies like IV fluids, antibiotics, oxygen therapy and nasogastric tube feeding as appropriate for patients with a DNAR order. The findings differed from O’Hanlon et. al (2013)’s study that surfaced some confusion over palliation and DNAR orders and only 36% of nurses felt that nasogastric tube feeding was appropriate for patients with DNAR orders. A recent study exploring physician attitudes towards withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in end-of-life care saw that most were more ready to withhold and withdraw haemodialysis than enteral feeds (Phua et. al, 2015). This difference could perhaps reflect cultural differences as the Asian culture consider food and nutrition as basic rather than medical care, representing love and hope for health and an expression of filial piety (Phua et. al, 2015).

Being a single-centred questionnaire-based study, there are limitations to be considered. Half of the respondents only had 5 years or less of working experience. Religious beliefs of the participants were also not included in this study and this could potentially contribute to the nurses’ views on end-of-life care. As such, findings should not be generalised to the nursing population in Singapore or Asia and a larger study is recommended to replicate the study findings.

A. Implications for Clinical Practice and Further Research

This study has multiple important implications. Firstly, there is clearly a need for more training and increased confidence to improve nurses’ involvement in the DNAR process. Nursing education has traditionally been focused on nursing diagnoses and the practical aspects of care. However, good communication skills surrounding end-of-life conversations are also required in order to advocate and better care for their patients. Perhaps nursing schools and hospitals should consider developing a structured programme to help improve communication skills surrounding difficult topics like end-of-life care and DNAR orders. Nurses should also be encouraged to be more involved in the DNAR process, encouraging open communication especially when expectations are not aligned with patients or family members and the treatment team.

Further research is recommended with a bigger population of nurses from various hospitals throughout Singapore and even Asia to provide more insight into this topic. Future research should also focus on testing the validity of the tool used in this study since it has not been tested after modification of the questionnaire.

As DNAR policies and issues surrounding withdrawal and withholding of care for these patients can vary from hospital to hospital, a national policy guiding physicians and nurses the matter could be developed to better equip healthcare workers with the necessary information needed to care for patients.

V. CONCLUSION

This study gives first insight into the perceptions and understanding of nurses surrounding DNAR orders and the care rendered for these patients. Being at the forefront, nurses should be encouraged to communicate openly with the medical team and advocate for their patients. In order to do so, structured programs and national policies should be considered so as to guide and support nurses through this process.

Notes on Contributors

Wee Li-Phing Clarice is an Advanced Practice Nurse at Ng Teng Fong General Hospital, Singapore.

Institutional Review Board (IRB)

Standard institutional review board (IRB) procedures were followed and approval was obtained by the author. IRB number 2016/00413.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr. Ross Freebarin and Dr. Faheem Khan for their valuable suggestions towards the study design and questions; and Dr. Yanika Kowitlawakul for her help in reviewing the article. In addition, the author would also like to thank Ms Syairah Binte Mohd Reduan and Mr. Johnny Wong for their assistance during the pilot study that contributed towards the final questionnaire used in this study.

Declaration of Interest

The author does not have any declaration of conflict of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

References

Fitz, Z., Fuld, J., Haydock, S. & Palmer, C. (2010). Interpretation and intent: A study of the (mis)understanding of DNAR orders in a teaching hospital. Resuscitation, 81(9), 1138-1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.05.014.

Gendt, C. D., Bilsen, J., Stichele, R. V., Noortgate, N. V. D., Lambert, M. & Deliens, L. (2007). Nurses’ involvement in ‘do not resuscitate’ decisions on acute elder care wards. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 57(4), 404-409.

O’Hanlon, S., O’Connor, S., Peters, C. & O’Connor, M. (2013). Nurses’ attitudes towards Do Not Attempt Resuscitation orders. Clinical Nursing Studies, 1(1), 43-50.

Phua, J., Joynt, G. M., Nishimura, M., Deng, Y., Myatra, S. N., Chan, Y. H. … Koh, Y. (2015). Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(3), 363-371. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7386.

Stewart, M. & Baldry, C. (2010). The over-interpretation of DNAR. Clinical Governance: An International Journal, 16(2), 119-128. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777271111124473.

*Wee Li-Phing Clarice

Email: clarice_wee@nuhs.edu.sg

Published online: 4 September, TAPS 2018, 3(3), 31-34

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-3/SC1056

Christie Anna1 & Lian Dee Ler2

1National Healthcare Group Polyclinics (NHGP), Singapore; 2Health Outcomes and Medical Education Research (HOMER), National Healthcare Group, Singapore

Abstract

Aims: The evidence on how reflection associates with clinical teaching is lacking. This study explored the reflection pattern of nursing clinical instructor trainees on their clinical teaching and its association with their teaching performance.

Methods: Reflection entries on two teaching sessions and respective teaching assessment data of a cohort of Registered Nurses participating in the National Healthcare Group College Clinical Instructor program (n=28) were retrieved for this study. Reflection entries were subjected to thematic analysis. Each reflection statement was coded and scored according to topics in relevance to three clinical teaching phases – preparation, performance and evaluation. Teaching assessment scores were then used to group the participants into different performance group. Reflection patterns derived from the coding scores were compared across these groups.

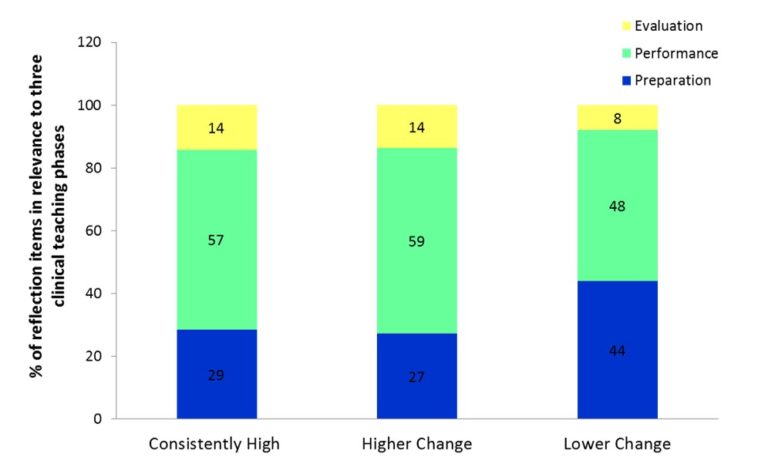

Results: Participants’ reflections focused on the performance phase (57% of reflected items), followed by preparation (30%) and evaluation (13%) phases. To assess the reflection pattern of trainees with differing teaching performance, participants whose teaching assessment scores were already high from first teaching session were classified into Consistently High group (score>22). Remaining participants were further categorized based on their improvement in teaching assessment scores into Higher Change (score difference>1) and Lower Change (score difference≤1). Compared to Lower Change group, participants in the Consistently High and Higher Change groups had higher trend of reflection focus on performance (57% and 59% vs 48%) and evaluation phases (14% and 14% vs 8%), but lower on preparation phase (29% and 27% vs 44%).

Conclusions: The finding suggests a possible role of reflection in teaching performance of nurse clinical instructors, warranting further investigation.

Keywords: Registered Nurses, Clinical Instructor, Reflective Thinking, Clinical Teaching, Reflective Journal

I. INTRODUCTION

The concept of reflection was first articulated by Dewey (Dewey, 1933) and it can be defined as ‘careful consideration and examination of issues of concern related to an experience’ (Kuiper & Pesut, 2004). Since its introduction, reflection has gained a lot of attraction in multiple disciplines and professions, including medicine and nursing. David Kolb, who developed the idea of ‘reflective learning’, is one of the most influential authors who proposed the incorporation of reflection as an educational approach (Kolb, 2015). Kolb suggested that learning should be a dialectic and cyclical process, and in his experiential learning model, suggested that experience is the basis of learning, which cannot take place without reflection. Meanwhile, reflection must be connected to action. In line to this conception, Donald Schön emphasized the importance of the ‘reflective practitioner’, describing reflective practice as the practice by which professionals can become aware of their implicit knowledge base and learn from their action or experience (Schön, 1983).

In the clinical setting, the focus of clinical teaching and learning has shifted from doing, to knowing and understanding (Won & Wong, 1987). In order to understand, one must process information or knowledge in a structured manner and reflect or link new experiences and knowledge with past experiences. This allows the learner to be a ‘reflective practitioner’ and learning to be meaningful. In addition, developing learners’ reflective skills enhances coherence between theoretical and practical components of education programmes (Hatlevik, 2012). Using reflection as a means to bridge the gap between theory and practice, and develop and articulate tacit knowledge is a widely used method in nursing literature (Johns & Joiner, 2002). As reflection is increasingly recognized as a crucial component in nursing education and practice (Nguyen, Fernandez, Karsenti, & Charlin, 2014), it was a timely initiative of the National Healthcare Group College (NHGC) to conduct a Clinical Instructor (CI) programme which factored reflection as an important aspect of the curriculum while assessing the association of reflection to nurses’ teaching performance.

The NHGC conducted a CI programme for the training and development of nursing clinical instructors. The development of reflective skills was incorporated as a methodology in the curriculum. The CI programme consisted of a total of sixteen days, of which six days were spent in the classroom, followed by ten days in the clinical setting as clinical practicum. In addition to the ten days clinical practicum period, participants were granted a one-month period, beginning from the last day of the programme to complete all assessment requirements of the programme. Participants of the programme were Registered Nurses (RNs) with a minimum of three years working experience in the clinical setting and a keen interest in the clinical teaching role. The aim of this study was to explore the reflective thinking of these nurse clinical instructors and its association with their clinical teaching performance during placement of the clinical practicum.

II. METHODOLOGY

Twenty-eight RNs were enrolled in the CI program and participated in this study which used quantitative thematic analysis to establish the relationship of reflective thinking and clinical teaching. During the one-month clinical practicum period of the programme, the CI trainees were required to carry out two clinical teaching sessions and log these cases into their Clinical Practicum Logbooks (CPL).

Clinical practicums took place in the same clinical setting where the RNs worked in. Following each clinical teaching session, they were to reflect upon their teaching and document their reflections in the Reflective Journal (RJ). The RJ contained a set of prompt questions to facilitate reflections: 1) what they had learnt from their clinical teaching; 2) what new learnings from classroom sessions they applied to the clinical setting; and 3) any concerns or doubts arose from their clinical teaching experiences. The CPL and RJ were in partial assessment requirements to successfully complete the CI programme.

At the end of the one-month clinical attachment period, both these documents were retrieved from the database for this study. The RJ was first subjected to thematic coding and analysis. The themes were coded deductively according to three clinical teaching phases – preparation, performance and evaluation. Two researchers who were initially blinded to participants’ teaching performances analysed the reflective journal. Each one independently read and coded each statement of the reflection from the first teaching log according to topics in relevance to the three clinical teaching phases. The two researchers’ respective coding results were then compared to ensure inter-coder reliability. Differences in interpretation were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. To quantify the reflection themes, each reflective statement was coded as one reflected item. The frequency of reflected item for each clinical teaching phase was thus derived. For example, if a participant reflected on the preparation teaching phase, this reflected item was counted towards the reflection frequency for the preparation phase theme.

We also extracted the teaching assessment scores for both teaching sessions from participants’ CPL. Performance scores were then used to group participants according to their teaching performances; how groups were categorised is explained in detail in the results section. In order to analyse patterns of reflective thinking across these groups, the frequency of reflected item for each clinical teaching phase was converted to percentage over the total reflected items.

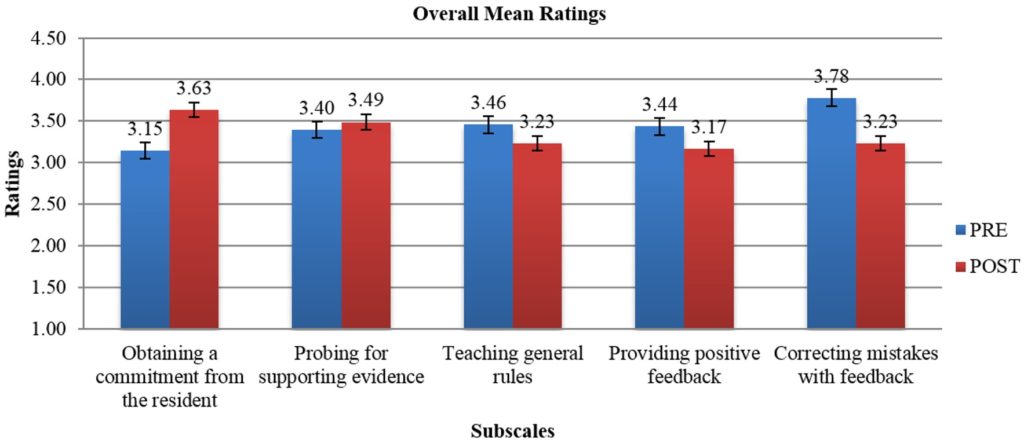

III. RESULTS

As suggested by Kolb, reflection is critical to connect experience to learning (Kolb, 2015). We thus analysed participants’ RJ on their first clinical teaching experience and explored their learning for clinical teaching through the change in their clinical teaching assessment scores between the first and second teaching sessions. Generally, participants’ reflections focused more on the performance (mean no. of reflected items = 3.8, 57%) as compared to preparation and evaluation (mean no. of reflected items are 2.0 and 0.9, or 30% and 13%, respectively) phases of clinical teaching (Figure 1). The teaching assessment scores of all participants either remained the same or improved across the two clinical teaching. The participants were classified into two groups according to their teaching assessment score in the first teaching. Fourteen participants whose teaching assessment scores were already high from the first teaching log were in the Consistently High group (score > 22). The remaining participants (score ≤ 22) were further classified based on the difference of teaching assessment scores between first and second teaching into Higher Change (difference > 1) and Lower Change (difference ≤ 1) for those with higher or lower improvements in clinical teaching, respectively. Participants in the Consistently High and Higher Change groups had higher trend of reflection focus on performance (57% and 59% vs 48%) and evaluation phases (14% and 14% vs 8%), but lower trend of reflection focus on preparation phase (29% and 27% vs 44%) when comparing to the Lower Change group.

Figure 1. Percentage breakdown of participants’ reflections focus according to their group category

IV. DISCUSSION

The use of clinical logs and reflective journals in the programme was to allow learners to define their experiences in their own words through reflective writing following a practical experience, and thus to validate their own unique experiences. Kobert (1995) illustrated that clinical logs and reflection allowed the learner to see his/her world within a larger context. In addition, learning shifts from a passive to an active process (Callister, 1993). Reflecting on their practice, the clinical logs and reflective journals provided the learners with tools for developing and improving their metacognitive awareness. The ability to develop and subsequently improve reflective thinking skills begins with the awareness of one’s own thinking patterns (i.e. their metacognition) (Fonteyn & Cahill, 1998).

This pilot study set out to describe patterns of reflective thinking among RNs following experiencing clinical teaching sessions. Results from this study provide preliminary support of the relationship between the reflection on different clinical teaching phases and clinical teaching performance of CI trainees. While all participants’ reflection focused mostly on performance phase, those who attained consistent and improved teaching performance showed a higher trend of reflection focus in the performance and evaluation phases but a lower trend of reflection focus in the preparation phase when compared with other participants. In line with this research effort devoted to identify effective reflective practice education (Asselin & Fain, 2013), the understanding of how reflection associates with clinical teaching can inform curriculum design on how nurse educators can teach or scaffold reflection to enhance clinical instructors’ clinical teaching skills.

The assessment structure of the CPL could be a contributing factor in participants’ reflection focus of the teaching phases. The overall weightage of the CPL teaching assessment was 30% of the CI programme. Other assessment requirements for CI programme included developing a lesson plan based on a microteaching conducting session, class participation and presentations during classroom sessions, and doing an online quiz before commencement of the programme. The RJ entries carried a total weightage of 20%, which meant each reflective entry carried a hefty 10%. The CPL teaching performance of the trainees was assessed by their total performance scores in each of the three teaching phases, with the performance phase carrying the highest scores. The preparation and evaluation phases each carried 5 marks, while the performance phase carried 15 marks. The weightage distribution given to each clinical teaching phase could also have been a factor which contributed to participants’ reflection focus – where they tended to focus on the performance phase as it carried the highest weightage of scores among the three teaching phases.

It should be noted, that study limitations included the use of a small sample, all recruited from a single cohort of the CI programme. All participants of this cohort of the CI program were included in this study, with no exclusion criteria or eliminating factors. The RNs were of varying nationalities, with differing years of working experience, holding various educational qualifications, and even differing in age and gender. These factors were not considered in this study on their impact or influence towards their clinical teaching ability, depth of reflection potential or the capacity to translate reflective thoughts into writing. Future research, taking these factors into account, will be critical to further establish the relationship of reflective thinking and clinical teaching.

V. CONCLUSION

Different patterns of reflection were associated with clinical teaching in nurse clinical instructors. Those with consistently good teaching performance, when comparing to those with low or no improvement in teaching, have higher trend of reflection focus in the performance and evaluation phases but lower in preparation phase of their teaching. Similar reflection pattern was also observed in those showing high improvement in teaching. The finding thus suggested a possible role of reflection in clinical teaching performance of nurse clinical instructors which warrants further investigation.

Notes on Contributors

Christie Anna is a nurse educator at the National Healthcare Group Polyclinics, Singapore. She is involved in the development of nursing education.

Lian Dee Ler is a research analyst at NHG-HOMER, the research unit within Education Office of National Healthcare Group, Singapore. She is involved in health profession education research.

Ethical Approval

This study does not require ethics approval as determined by the NHG Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB), Reference 2017/00156.

Declaration of Interest

C. A. is an employee of National Healthcare Group Polyclinics and L.D.L. an employee of National Healthcare Group Singapore. The authors have no financial, consultant and other relationships that might lead to competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This pilot research project was supported by the following colleagues who provided their expertise that greatly assisted the research:

Lim Yong Hao, Research Analyst, NHG-HOMER, Group Education & Research;

Eileen So, Executive, NHG College;

Dong Lijuan, Assistant Director of Nursing, Nursing Services, NHG Polyclinics; and

Poh Chee Lien, Assistant Director of Nursing, NHG HQ, Group Education & Research.

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships.

References

Asselin, M. E., & Fain, J. A. (2013). Effect of reflective practice education on self-reflection, insight, and reflective thinking among experienced nurses: a pilot study. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 29(3), 111–119.

https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0b013e318291c0cc.

Callister, L. C. (1993). The use of student journals in nursing education: Making meaning out of clinical experience. Journal of Nursing Education, 32(4), 185–186.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Lexington (Massachusetts): D. C. Heath.

Fonteyn, M. E., & Cahill, M. (1998). The use of clinical logs to improve nursing students’ metacognition: A pilot study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(1), 149–154.

Hatlevik, I. K. R. (2012). The theory‐practice relationship: reflective skills and theoretical knowledge as key factors in bridging the gap between theory and practice in initial nursing education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 868–877.

Johns, C., & Joiner, A. (2002). Guided reflection: Advancing practice. Osney Mead, Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Kobert, L. J. (1995). In our own voice: Journaling as a teaching/learning technique for nurses. Journal of Nursing Education, 34(3), 140–142.

Kolb, D. A. (2015). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education.

Kuiper, R. A., & Pesut, D. J. (2004). Promoting cognitive and metacognitive reflective reasoning skills in nursing practice: Self-regulated learning theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(4), 381–391.

Nguyen, Q. D., Fernandez, N., Karsenti, T., & Charlin, B. (2014). What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Medical Education, 48(12), 1176–1189.

https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12583.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic books.

Won, J., & Wong, S. (1987). Towards effective clinical teaching in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 12(4), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1987.tb01360.x.

*Christie Ann

Email: christie_anna@nhgp.com.sg

*Lian Dee Ler

Email: lian_dee_ler@nhg.com.sg

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2019, 4(1), 55-58

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-1/SC2000

Ikuo Shimizu, Junichiro Mori & Tsuyoshi Tada

Centre for Medical Education and Clinical Training, Shinshu University, Japan

Abstract

Consensus formation among faculties is essential to curriculum reform, especially for the clinical curriculum. However, there is limited evidence on the model of workshop that is necessary for curriculum reform. In the current project, we aimed at developing a beneficial workshop method for building consensus and reaching educational goals in curriculum reform. We compared the two types of workshop models. First, we conducted workshops using standard group work model with fixed group members. Then we used a revised workshop model. In the revised model, all but one group member moved their seats after the first round of discussion. In addition, we reserved time for plenary presentations and discussions after each round. We called the model “Modified World Café” workshop named after World Café, a collaborative dialogue method. With this design, not only we were able to achieve significant improvement of appropriate products and better consensus, but also attained several educative goals. Since the model combines characteristics of the standard group work and World Café concept, it might be useful in facilitating the sharing of new knowledge and creating consensus.

Keywords: Curriculum Reform, Workshop, Consensus Building, World Café

I. INTRODUCTION

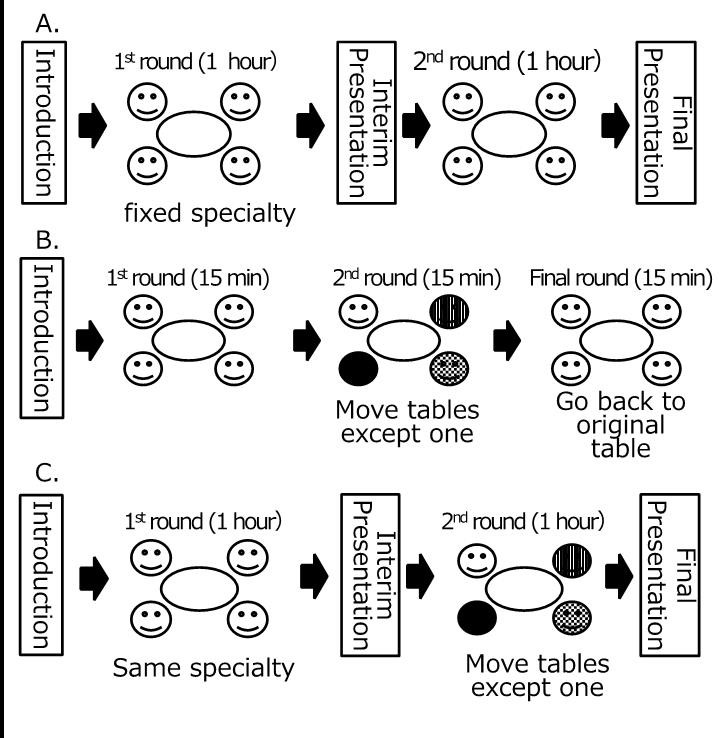

When medical education managers conduct the curriculum reform in medical schools, they must plan for an effective implementation of the new outcomes of the curriculum, especially in the curriculum reform of clinical years when more diverse community clinician-educators at various educational environments are involved (Takamura, Misaki, & Takemura, 2017). Therefore, it is desirable that the curriculum is reformed by taking into accounts of the opinions from stakeholders at multiple specialties and reaching a consensus among them. In medical education, workshops have been performed for such a reform (Steinert, 2014). The standard workshop consists of small group discussions with fixed members throughout the schedule (Figure 1A), however, the effectiveness of this workshop design has not been well explored.

The World Café (Brown & Isaacs, 2005), a series of short group dialogues with table rotations (Figure 1B), is useful for building consensus since it relies on a participatory and collaborative network of conversations (Health Profession Opportunity Grants, 2015). However, one concern to apply World Café for establishing outcomes is that it may not be suitable to establish a new curriculum since it is just a dialogue process rather than a workshop to construct valid products and short discussion time may make discussions superficial and unfruitful.