Issue 54

Jul 2025

SPECIAL FEATURE

By ASSOCIATE Professor Cuthbert Teo, Editorial Board Member, SMA News, Singapore Medical Association

This 14-part series on the history of Medicine in Singapore was originally published by the Singapore Medical Association.

The Medical School

In the early 19th century, Singapore’s first doctors came from Britain and India. The doctors were all generalists, not specialists. They had to perform whatever duty expected of them. They served in all the three Straits Settlements (SS) and were transferred according to the exigencies of the service. From 1870, suitably qualified young men were sent annually by the government to Madras Medical College to train as assistant surgeons. They were bonded to serve the government on their return.

The first proposal to start a medical school in Singapore was made in 1889 by Dr Max Simon, the Principal Civil Medical Officer. The school was to have been established in 1890, but no candidate could pass the entrance examination. In 1891, only two passed the examination, and the plan was thus abandoned.

In September 1904, a second and successful attempt was made. Representatives of the Chinese and other non‑European communities led by Mr Tan Jiak Kim petitioned the Governor of the SS, Sir John Anderson, for the establishment of a medical school. Mr Tan Jiak Kim was the first president of the Straits Chinese British Association, formed on 17 August 1900, which was the forerunner of the Peranakan Association. Sufficient funds amounting to S$87,077.08 were raised, with the largest amount of S$12,000 from Mr Tan himself.

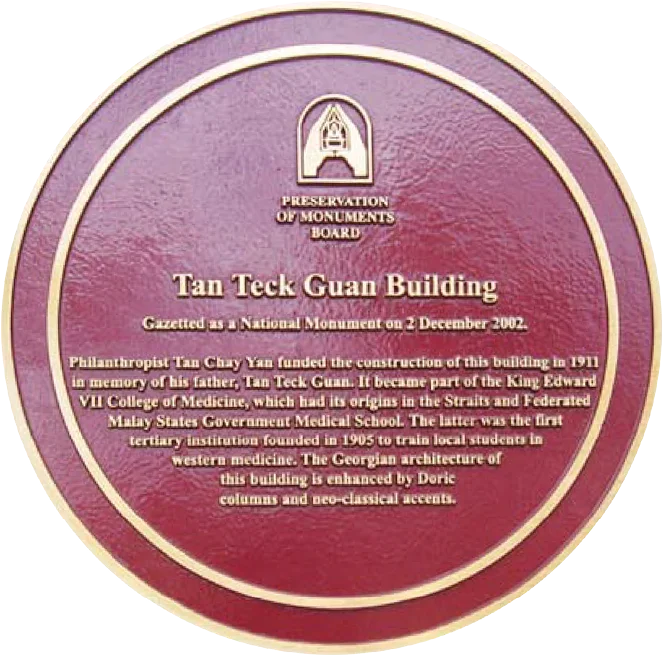

The work of this group is memorialised in two historical plaques on the side pillars of the main entrance to the Tan Teck Guan Building. The inscription on the plaques is in Chinese and reads as follows in English (official translation by Mr Choo Ping Chyuen, commissioned by the Ministry of Health in 1992):

The good government depends upon capable leaders supported by the cooperative effort of public-spirited people. Such government is able to undertake tasks and complete projects. The Governor of Singapore, Sir John Anderson KCMG, and King Edward VII, have lived up to their high reputation since assuming office and are highly admired by the multitude. They have the welfare of people at heart and pursue various policies and measures beneficial to people. Those who are benefited naturally eulogise to the utmost. The most unforgettable deed is the establishment of a medical school. Not all people can live comfortably without suffering from illness. A sick person especially depends upon the diagnosis and treatment of a prominent physician to pull him through. A patient needs special care during his convalescence so that his life may be preserved. Those who learn hastily and have a smattering of knowledge but without proper qualification often come out to practise medicine. Their erroneous diagnosis and treatment is serious. Both the Governor and the King know that medicine is closely related to human health. In order to relieve people from the suffering of disease and ailments it is necessary to train medical students. In order to provide the training it is necessary to establish a medical school. Therefore an appeal has been made to the public to raise money for this project. Happily a big sum has been raised. This fund can be used to appoint brilliant teachers to impart medical knowledge and skill to students. After graduation, the students may become better doctors than their teachers. Many patients will be able to preserve their life because of the correct diagnosis and successful treatment. The local people are so kind, noble and cooperative that a big sum of money has been raised. Such positive expression of charity is highly exemplary. The benevolence of the Governor and the King together with the magnanimity of a kind-hearted public is worthy of record. Therefore the inscription is carried on this beautiful stone to preserve this record from falling into oblivion. All the good names of donors are carved on another beautiful stone for future reference.

Official opening of the Tan Teck Guan Building. Photo credit: SGH Museum.

With the funds, the buildings of the old Female Lunatic Asylum at Sepoy Lines were converted into classrooms, laboratories, dissecting rooms and offices. The medical school was founded on 3 July 1905, and was named the Straits and Federated Malay States Government Medical School. The Medical Library was first housed in the students’ reading room within the Medical School, which was converted from the vacant old Female Lunatic Asylum (at a cost of S$1,000). The remaining funds went to equipment (S$10,000) and scholarships for students (S$60,000). The school entrance was a gate with iron bars.1 A pavement led from the iron gate to the entrance of a covered passage way. On either side of the pavement stood a two-storey building for the residence of the warders. Beyond the entrance, on the right, was a small building used as a lecture room where lectures on osteology, physiology, botany and hygiene were given. At the back of this building was a bigger building housing the Government Analyst, which was not part of the medical school. To the left of the entrance stood a wooden bungalow, which housed the principal’s office, his clerk’s office and two rooms that served as a reading room and a rest room for students. Behind this, separated by a narrow lawn, there was a large building used for dissection. Still further back, there was a similar sized building which served as the physiology lecture room in 1906, when equipment like microscopes were ready. Chemistry and Physics were taught in the government laboratory at the corner of Hill Street and Coleman Street (where Hill Street Central Fire Station stands today).

The first enrolment consisted of 23 students—nine Chinese, six Eurasians, five Tamils, one Malay, one Ceylonese, and one European. Sixteen students attended the full course, while seven attended a two-year course for hospital assistants. Each was given a scholarship of S$15 per month with a yearly increment of S$1 per month for the next four years, and they were lent free textbooks. The main causes of death at the time were malaria, dysentery, beriberi (its aetiology was still unknown at the time), tuberculosis (for which there was no antibiotic treatment available at the time) and venereal disease (penicillin had yet to be discovered; gonorrhoea was treated with mercurial compounds). Teaching was done by government doctors, two army surgeons, and five private practitioners.

The old Female Lunatic Asylum. Photo credit: SGH Museum.

The plaque situated at Tan Teck Guan Building. Photo credit: SGH Museum.

At the opening ceremony on 28 September 1905, Sir John Anderson (Governor of the Straits Settlements, 1904–1911), spoke thus to the first batch of medical students: “I am sure you will realise the best hopes of the government and the community. It is to you that government looks especially. You are of the East, and to you they look, to break down the walls of native prejudice and overcome his ignorance. You have access as the Westerner has not, to the inmost household in the East, and it is a very real battle that will have to be fought, and I think, with the training you will acquire here, you will go forth well-equipped and determined to win in the real spirit of the profession. And in a few years’ time, you will overcome them and the community will reap the benefit of an increasingly healthy population, a diminishing death rate and improved conditions of life everywhere.”

At the time, Dr Donald K McDowell was the Principal Civil Medical Officer. Dr Gerald D Freer, who was the Colonial Surgeon in Penang, and one of the first two house surgeons appointed to the general hospital in Singapore in 1890, was appointed Principal of the medical school and he taught anatomy. Dr Robert D Keith was appointed Physiologist and Assistant Pathologist. The medical school was also permitted under the Morphine and Poison Ordinance to issue a Pharmaceutical Licence.

One of the lecturers in the medical school when it opened was Dr Gilbert E Brooke (lecturer in hygiene). He migrated to Singapore in January 1902 and was appointed Deputy Coroner of Singapore in 1906, then Justice of the Peace in 1908. Brooke published several medical textbooks. He became Chief Health Officer in January 1914, and co-authored the book titled One Hundred Years of Singapore Volume I and II, with Walter Makepeace, published in 1921, giving a glimpse into life in Singapore at that time. He died in 1936 in Singapore.

A/Prof Cuthbert Teo is trained as a forensic pathologist. The views expressed in the above article are his personal opinions, and do not represent those of his employer.

Chen SL. Medical education during early years: reminiscences from the first intake. In: Lim KH, ed. 75 Years of Our Alumni: At the Dawn of the Millennium. The Alumni Story. Alumni Association/ Singapore University Press, 2000:94-7.

More from this issue