Issue 52

Nov 2024

AFFAIRS OF THE HEART

By Timothy Ng Yu, Former Research Assistant/Trainee at the Cardiovascular-Metabolic Translational Research Programme (CVMD TRP)

Pursuing scientific knowledge, a young scientist discovers himself.

During my undergraduate years, I attended a lecture by Professor Roger Foo on the captivating work from his lab, from illuminating the molecular and epigenetic underpinnings of heart failure to the development of therapeutic strategies. In hopes of digging deeper into the intricate mechanisms driving heart failure, I joined the Cardiovascular-Metabolic Translational Research Programme (CVMD TRP) as a final-year project (FYP) student and subsequently, a research assistant.

Of mice and models

In the field of CVMD, preclinical models have become indispensable. Whether in the form of engineered heart tissues or animals, experimental manipulation of these systems allows us to study the mechanisms of disease pathology while also serving as a platform for target validation and drug discovery. Naturally, I felt privileged when I was given the opportunity to characterise a transgenic mice model during my FYP. In this system, a form of cell death known as apoptosis could be selectively induced in heart muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes. Given how elevated levels of cardiomyocyte apoptosis is characteristic in heart failure, this model serves to answer lingering questions, such as how apoptosis could play a role in the exacerbation of heart failure.

I thoroughly enjoyed the rigour of driving a research project. It broadened my knowledge of heart failure, enhanced my ability to formulate effective research questions, and sharpened my critical thinking during analyses of experimental findings. At times, it could be particularly exacting when the findings from some assays were not commensurate with others, or when arrival at crossroads called for decisions to be made. On a more practical level, I found an increasing need to manage my time and resources effectively as the school term got busier—staggering different experiments that extended for days, planning ahead and juggling academics with lab work.

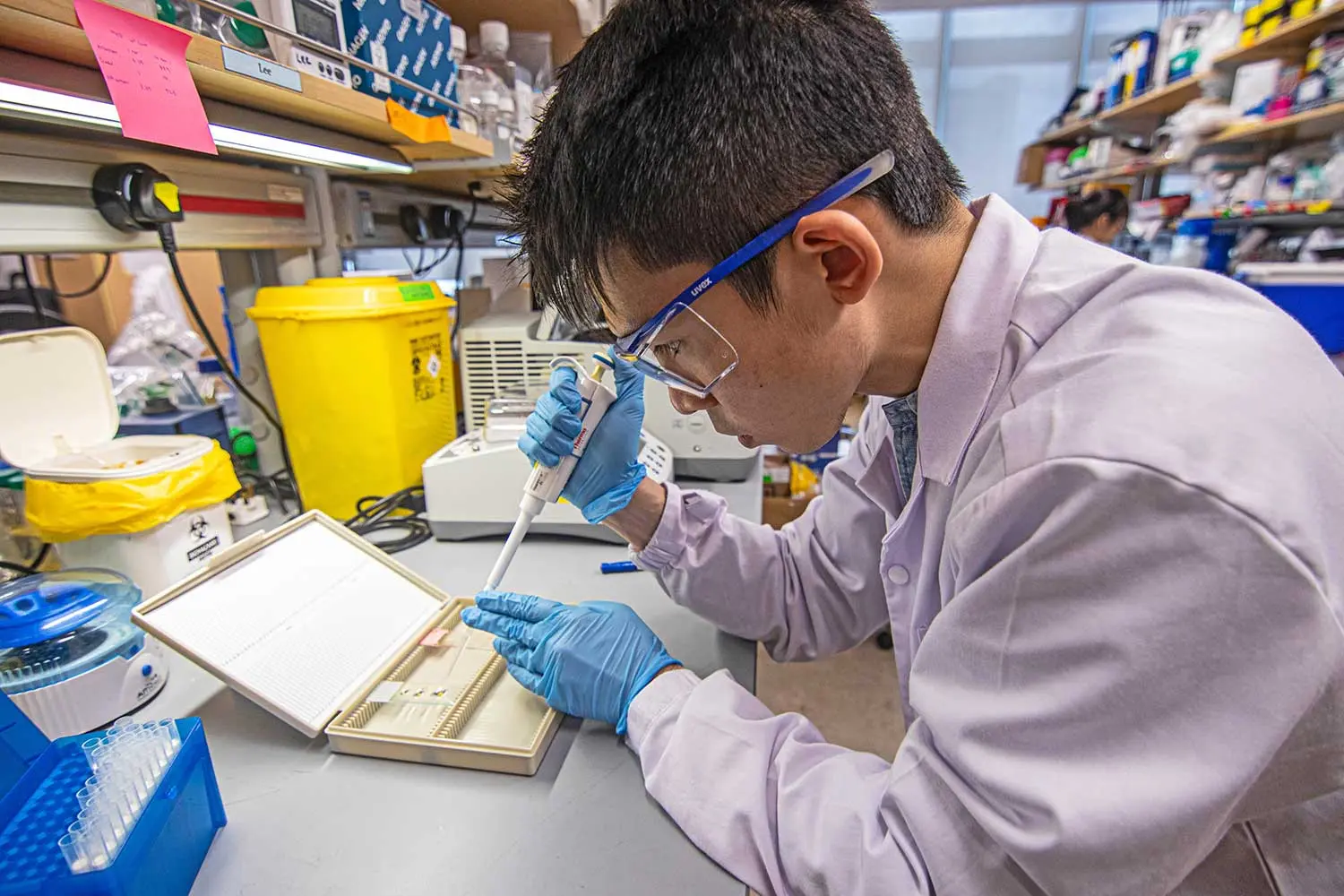

Moreover, the project nudged me to grow in my character as much as it did with my research skills. It demanded discipline to hone my experimental techniques, one of which was histology. I spent hours in the lab sectioning mice hearts, staining them and visualising them under the microscope to quantify the rate of apoptosis, as well as scarring and changes in cardiac architecture, all of which are hallmarks of cardiac pathology. While some staining techniques were routine, other histology skills demanded dexterity and precision.

Performing histological staining of tissue sections, making every drop count!. Photo credit: Dr Rijan Gurung

Personally, achieving mastery over these techniques was an exercise in resilience and a test of humility. As I encountered failures, I found the need to acknowledge my shortcomings, whether it was a lack of focus or speed, or cultivating a persevering attitude. I gradually adopted a growth mindset, acknowledging failed experiments as teachable moments which could pave the way for future growth. At the same time, having a presence of mind made the journey easier. Whenever I felt inundated by the overwhelming experiments, flustered by the failed ones, or dejected by negative results, I learnt to shift the spotlight away from mindless preoccupation over setbacks and fix my gaze on the present, knowing that whatever I do now matters.

Perhaps this is what science is. As the narrative of science unfolds with each new finding, a parallel trajectory of personal and professional development emerges with the researcher growing in resilience and maturity with each day in the lab.

As the narrative of science unfolds with each new finding, a parallel trajectory of personal and professional development emerges with the researcher growing in resilience and maturity with each day in the lab.”

It’s all in the genes

Upon the completion of my FYP, I embarked on a new project as a research assistant which aims to leverage genetic tools such as massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) to understand how variation in the non-coding regions of our genome affects the way nearby or distal genes are expressed. Our role was to study how such variation affects the function of cardiomyocytes, and consequently, their role in heart failure.

Taking on this role, I found myself spending fewer hours sectioning heart tissues and more time cloning DNA constructs and culturing stem cells. It was nothing less than a humbling experience. While I was previously exposed to the fundamentals of epigenetics in my undergraduate modules, this immersive, first-hand experience expanded the breadth and depth of my practical knowledge in these areas. The research process afforded me the opportunity to delve into the complexities and nuances of epigenetics, while getting my hands dirty in molecular cloning and CRISPRi opened my eyes to the cornucopia of genetic tools today and how they allow us to interrogate clinical variants for their roles in heart disease.

The Foo lab; the people I work with.

From the benches to the community

However, genetics is only one part of the equation. With growing evidence of the impact of environmental and lifestyle factors on our health, it is imperative to understand how they shape cardiovascular diseases. Hence, I felt exceptionally fortunate to witness how Project RESET, an initiative of the CVMD TRP, sets out to do that by bringing science from the benches to the community. I was duly impressed by how such projects require not just scientists but a formidable, multidisciplinary team of clinicians, clinical research coordinators, and engagement staff. From the grand launch of project RESET to volunteering in outreach sessions, I have become convinced that translational research is a collective endeavour, with every individual playing an important role. Science only moves when people move.

Science moves when people move

Indeed, “science moves when people move.” Throughout my experience in the CVMD TRP, this phrase rings true. I have benefitted immensely from the wisdom and dedication of my mentors and the inspirational community of scientists who motivate me to go above and beyond.

CVMD trainees in active discussion with leading professors in cardiovascular and metabolic research. Photo credit: Dr Rijan Gurung

In every sense, my mentors served as role models. I gained as much from the way they handled their projects as I did from the meetings where we brainstormed my project plans and pored over the data analysis. At the beginning, how they managed their experiments alongside their mounting tasks and responsibilities eluded me. However, I began to gain clarity after they shared their advice with me and walked their talk.

Beyond my mentors, the wider science community has also played an instrumental role in shaping my growth as a scientist. Presenting my project, whether during poster presentations or meetings, gave me the opportunity to work on the way I communicate science. In the process, it dawned upon me that constructing a coherent narrative from the datasets and tailoring it to different audiences was no mean feat. During conferences and meetings with esteemed leaders in the field, I was captivated by the inspiring accounts of their own research journeys. It amazed me how their passion for science, innovative thinking and character got them through the valleys in their career and led them to their peaks. Their excitement for research was truly contagious.

In summary, what is moulding me as a researcher lies in both the spoken and the unspoken. I realise that it isn’t just about the probing questions which my mentors ask, or the synergy when I receive fresh insights from experts in areas beyond my discipline. It’s also about the spirit of research that is embodied in each individual: to seize each day in the pursuit of science, and to spur others to do the same.

Timothy Ng is a MD-PhD student at Duke-NUS Medical School.

He wrote this article when he was a research assistant at NUS Medicine CVMD TRP.

More from this issue

A WORLD IN A GRAIN OF SALT

My Student-Inspired Forays into The Microverse