11-13 Mar (outside LT26)

The Open House will showcase the different undergraduate courses the Department hosts.

Issue 52

Nov 2024

A WORLD IN A GRAIN OF SAND

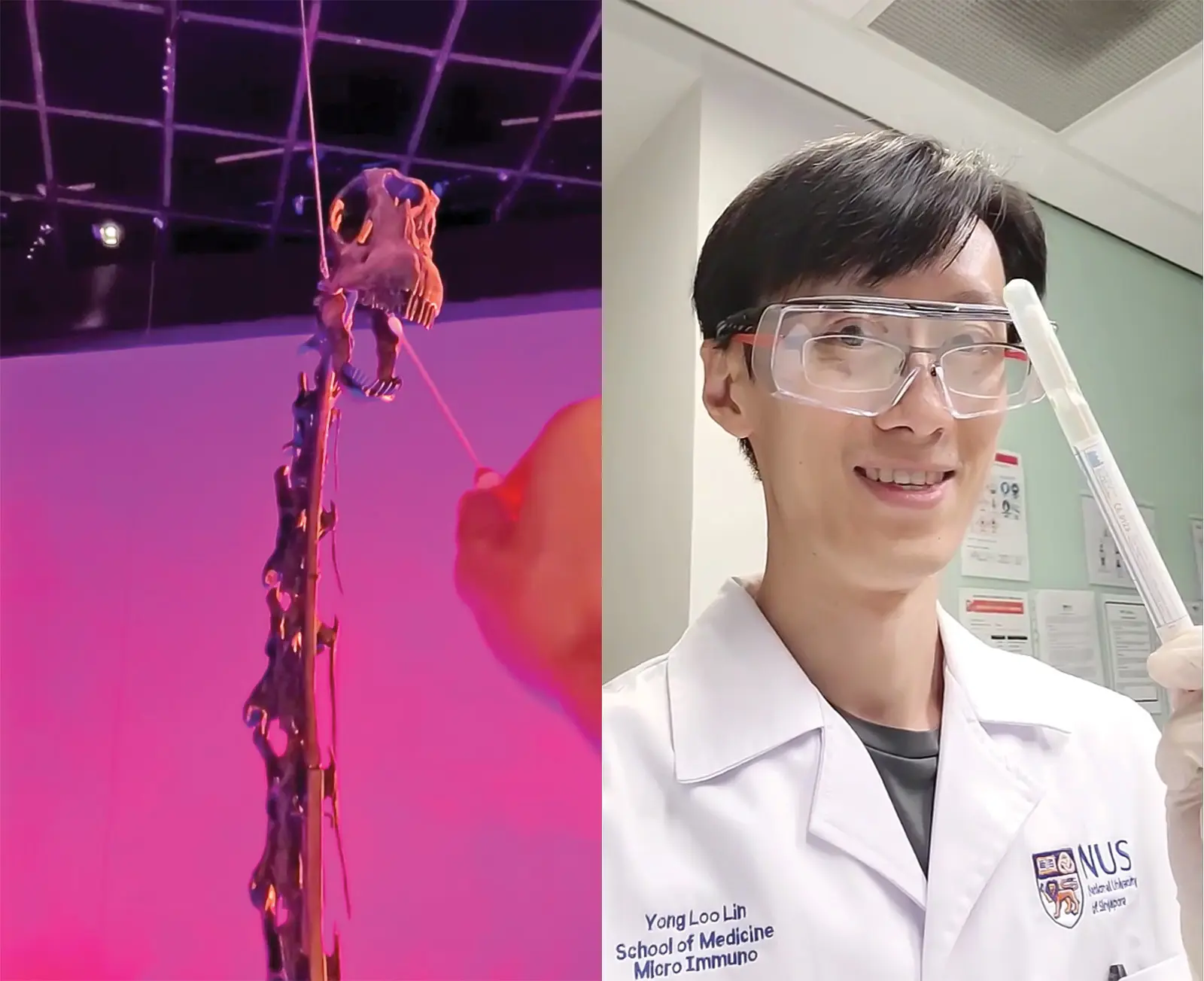

By Dr Ch'ng Jun Hong, Department of Microbiology and Immunology

“Adventure is not outside man; it is within.” George Eliot.

Influencers travel to exotic destinations and vlog about surreal experiences. Yet every microbiology lecture is also an opportunity for adventure—each class an invitation to explore something one may have never considered: an invisible world of microbes right under our noses.

Steve Spangler, American TV personality, author and STEM teacher once said: “Students want to be in the presence of a teacher who has lost their mind! They want to be around somebody who is so passionate about learning that they were willing to go to the nth degree to share their passion and excitement”. With a PhD and over a decade in microbiology research, it is not a stretch to see I fit the first criteria. As university educators, we cherish the opportunity to profess about topics that resonate with us. Whether through lectures or wet-lab practicals, I bring students through a roller coaster of experiences: marvelling at a parasite’s complex life cycle, exploring the social impact of diseases, and having students contribute towards disease control amongst the world’s poorest. I eagerly jump around in a puddle of my favourite microbes, encouraging students to get their feet wet too!

But sometimes, learning can be a little bit scary when we venture beyond our comfort zones. In the middle of a semester, I always ask my General Education class (Microbes which Changed Human History) to vote for a topic they would like me to link to microbiology—however wild the idea may be. And every year, I have a panic attack as the deadline approaches to deliver the student-selected lecture! But the thrill of exploration and the transformative power of learning are experiences we must live out and not just talk about.

The first year I tried this, in 2021, students selected the topic of ‘zombies’. Perhaps I should have seen this coming since Halloween was just around the corner, but students stared bemused while my brain rebooted at the lectern: how was I to teach real science through the quagmire of B-grade Hollywood theatrics? As I bounded down the rabbit hole of research, I realised that fact was stranger than fiction: fungi could control insect behaviour while their bodies were half-eaten from infection, blood parasites turned mice fearless to their natural predators, and neurotropic viruses transformed lumbering racoons into salivating savages. Science fiction, it seems, is but a pale imitation of the microbial world’s true wonders.

In the second year, students asked about ‘marine microbiology’. By coincidence, bioluminescent dinoflagellates made their electric-blue appearance on our fair shores (and the front pages of local newspapers) but a week later! In addition to expert interviews with colleagues from the Department of Biological Sciences (Associate Professor Huang Dan Wei and Dr Emily Curren), and a trip down Changi Beach to experience the phenomenon first hand, I also had a legitimate excuse to view my first plankton under the microscope. I was floored by how intricately beautiful these organisms were, floating right there in the sea water, completely invisible to the naked eye. I ended up proposing Sentosa’s next bespoke attraction to my class: a private bioluminescent tide pool for the rich seeking a psychedelic, family-friendly eco-adventure!

Extracting DNA from the dental plaque of the resident Diplococcus fossils.

In 2023, my class set me up on a date with ‘dinosaurs’. I could never have imagined this would lead to me having an exchange with the man whose life’s work inspired Jurassic Park. Working with the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, I filmed a spoof of me trying to extract DNA from the dental plaque of the resident Diplococcus fossils (Figure 1). As it turns out, dinosaur DNA (and by extension dino-era microbial DNA) has never been sequenced in any very meaningful way since DNA isn’t stable over such extended duration. Without DNA sequences, electron micrographs of a rod- or cocci-shaped bacteria embedded in fossilised dino-poop (coprolite) was neither informative nor compelling for a classroom narrative. Thankfully, Professor George Poinar Jr. (Oregon State University) had identified different life cycle stages of the blood parasites (Paleoleishmania) beautifully preserved in amber-embedded sand fly specimens from Cambodia. These showed striking resemblance to modern day Leishmania parasites (causing leishmaniasis in people today), and the sheer abundance of parasites in sand fly specimens allowed Prof Poinar to predict that these parasitic infections were extremely common in dinosaurs roaming that area. This revelation completely blew my mind! I eagerly wrote to Prof Poinar who gladly furnished me with an e-copy of his book “What Bugged the Dinosaurs: insects, disease and death in the Cretaceous”.

Students didn’t disappoint this year either with their topic: ‘Can Microbes Make Me Smarter?’ I defied my instincts to dismiss the question and stay open minded, and was duly rewarded. Not only did I better understand “intelligence”, thanks to an interview with Dr Lee Li Neng from the Psychology Department, but I also discovered some groundbreaking publications on the topic vis-à-vis microbiology. The latest cross-sectional studies showed strong correlations between the gut microbiome and intelligence, while prospective studies have demonstrated the effect of the adult gut microbiome on cognitive health/ageing. Could the toilets at NUS hold more treasure than our libraries? Perhaps the adage of “looking within” for the answers holds more than poetic wisdom.

Through these academic expeditions, neatly packaged as recorded lectures, I showcase my journey of learning to embolden students to partake in their own adventure. Later in the semester, I am rewarded with provocative group project presentations and stirring term papers—precious snapshots of students on their personal journeys of discovery. For many, these classroom adventures are what they proudly reflect upon even as the course draws to a close.

As the Department of Microbiology and Immunology commemorates its Centennial in 2025, I would like to invite you to join us in 4 little forays into the micro-cosmos: Firstly, the Department’s Open House in March will showcase our fascinating undergraduate course offerings and fantastical research pursuits. Secondly, we will be hosting Learning Journeys for MOE school students and teachers to experience microbiology and immunology education at our Department in May. In July, we will be organising a Microbiology & Immunology Symposium on Campus to commemorate our research milestones and international collaborations. Finally, we will be organising a local microbiology and immunology social media competition in December. Details to follow in our socials. Join us as we dive in to observe the enchanting microbial world hidden in an unassuming grain of sand.

As we wrap up this MediCine column for now, we thank the Editors for giving our Department a platform to share the many lessons we have learnt along our journeys of discovery. We hope these heartfelt commentaries have enriched your lives and allowed you to see ‘heaven in a wild flower’. Happy Adventuring!

We thank the Editors for giving our Department a platform to share the many lessons we have learnt along our journeys of discovery. We hope these simple heartfelt commentaries have enriched your lives and allowed you to see 'heaven in a wild flower'. Happy Adventuring!”

The Open House will showcase the different undergraduate courses the Department hosts.

We will organise Learning Journeys for MOE school students and teachers to experience microbiology and immunology education at our Department.

A Microbiology & Immunology Symposium will be held on Campus to commemorate our research milestones and international collaborations.

More from this issue