Issue 51

Aug 2024

ALUMNI VOICES

By Wong Kim Hoh, Features Editor at The Straits Times

But despairing and wringing hands over the situation will not do, the orthopaedic surgeon adds.

Dr Ang Swee Chai cannot stop thinking about the war now raging in Gaza.

“I’d go back immediately if I can,” says the diminutive orthopaedic surgeon who has treated war victims under heavy bombardment in Lebanon as well as the occupied territories of Gaza and the West Bank for the past 35 years.

But she can’t, and not just because humanitarian group International Rescue Committee has just declared Gaza to be the “most lethal place on earth to be an aid worker”, after the killing of 7 international charity workers by an Israeli air strike on 1 April 2023.

“My health is pretty lousy,” says Dr Ang, who was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer in 2021. “I’ve had a year of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and now I’m on hormone blockers.”

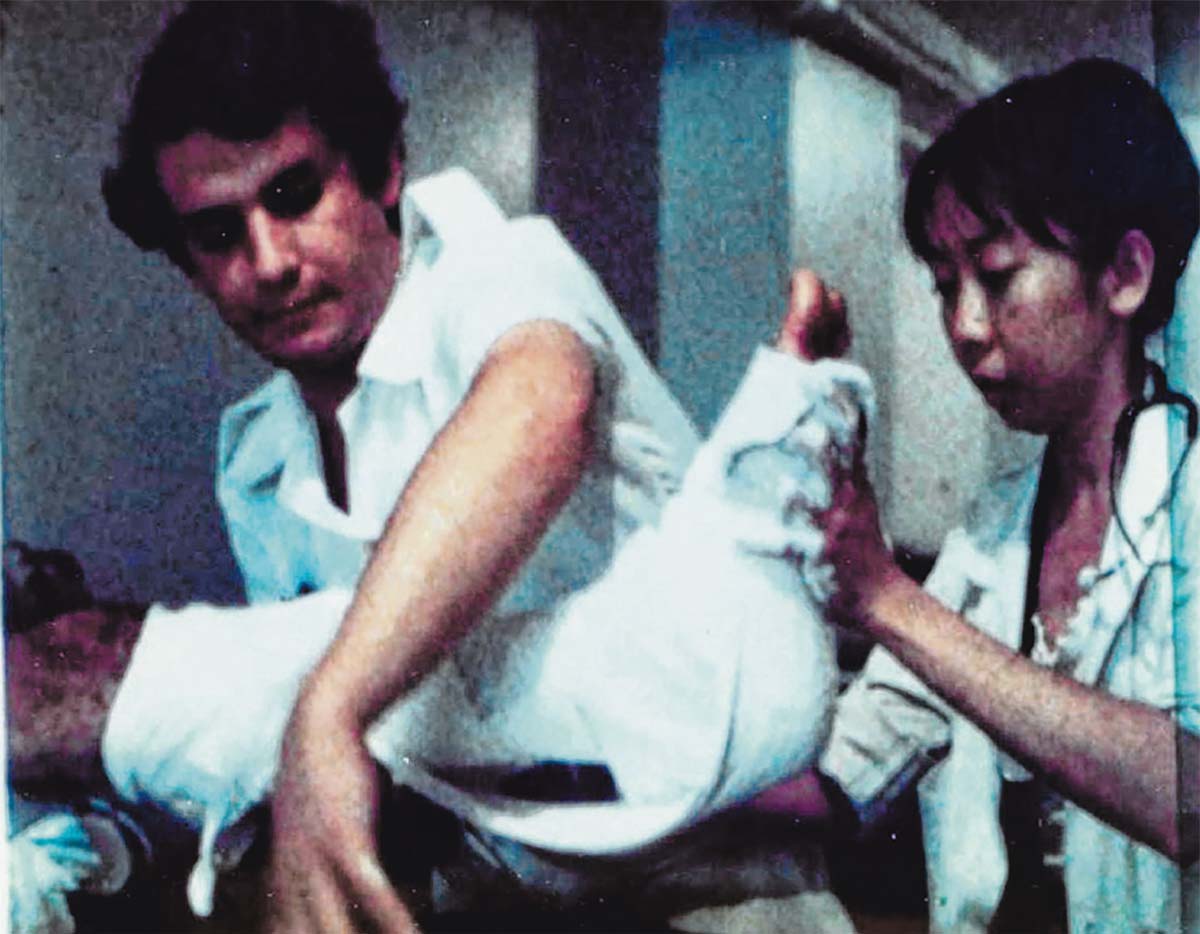

Dr Ang and nurse Ahmed tending to a patient at Gaza Hospital in the Sabra-Shatila refugee camps in 1982. PHOTO: ANG SWEE CHAI

The 76-year-old—who witnessed the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre when the Israel-backed Lebanese Phalangist militia killed between 800 and 2,000 Palestinian refugees and Lebanese civilians over 43 hours—has been on tenterhooks since 7 October 2023, when militant group Hamas launched an attack on Israel, triggering a war which has turned into a humanitarian crisis.

“Going into Israel, taking hostages and killing is not the right way. But does it legitimise flattening the whole of Gaza, killing so many people, destroying all their hospitals and starving them? Women are cooking grass to feed their children,” Dr Ang says of the conflict which has claimed more than 30,000 Palestinian lives since it started, according to Gaza health officials.

“There are 7,000 people under the rubble, 400 health workers and 100 journalists killed, 50,000 pregnant women giving birth in tents or in the rubble,” she says, passionately rattling off figures seared into her brain.

Standing at just 1.49m tall, the wisp of a woman has lived—as the Tom Jones song goes—one hell of a life.

Born in Penang but raised and educated in Singapore, she is the widow of lawyer and activist Francis Khoo, who fled Singapore for London in 1977 to avoid questioning by the Internal Security Department (ISD) during a security sweep targeting communists. She joined her husband as a political exile in Britain, where she has lived for the last 47 years and is now a citizen.

The first female consultant orthopaedic surgeon at London’s renowned St Bartholomew’s Hospital, she went to war-torn Lebanon to treat the wounded in 1982 when Israel invaded the country. There, she worked in the hospital of the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp and witnessed, a month later, the historic massacre and other horrors quite unimaginable. Her life has not been the same after that.

“I vowed to do something for the Palestinians,” she says.

And she has. In late 1982, she went to Jerusalem to testify at the Kahan Commission, set up to investigate the massacre. She said then: “If we are silent in the face of massacres, we would not be fit to be doctors and scientists. We have to be witnesses.”

Over the last 4 decades, she has returned to Lebanon and gone to Gaza several times to help casualties of the long-running Israel-Palestine conflict. In 1984, she co-founded Medical Aid For Palestinians (MAP), a British charity that offers medical services to and advocates for Palestinians’ rights to health and dignity.

Dr Ang ran MAP’s humanitarian programme in Lebanon between 1986 and 1989, after which she worked as an orthopaedic consultant for the United Nations (UN) and World Health Organization (WHO) in Gaza. The surgeon is still an honorary patron of MAP, which was one of the first organisations to respond to the current crisis in Gaza.

Dr Ang Swee Chai treated patients in war-torn Lebanon in the 1980s and co-founded Medical Aid for Palestinians in 1984, among other things. Now a British citizen, she was in town recently to receive the 2024 Fellow Award from the Harvard Club of Singapore. ST PHOTO: ONG WEE JIN

Her experiences have led her to pen From Beirut To Jerusalem (1989) which chronicles her account of the Sabra and Shatila massacre, and co-author War Surgery: Field Manual (1995) with Norwegian surgeons Hans Husum and Erik Fosse.

The late Yasser Arafat—who was also chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organisation—conferred upon her the Star of Palestine, the highest award for service to the Palestinian people, in 1987.

Dr Ang—who joined the Freedom Flotilla to break Israel’s blockade of Gaza in 2018 and was imprisoned for 3 days after the Israeli navy intercepted their vessel—has spoken passionately about the plight of the Palestinians and the horrors of war in many places, including the British House of Commons and Scottish Parliament. She did so again on 2 occasions in Singapore recently.

The first was at the presentation of A Woman Surgeon With The Palestinians at a Harvard Club Of Singapore (HCS) dinner on March 26, where she received the HCS 2024 Fellow Award. She was lauded for “not only demonstrating excellence in her field of orthopaedic surgery” but also putting “these special skills in the service of human beings, not just in her professional work and her community, but for a particular people crying out desperate for help for their lives and safety”.

The next day, she spoke at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore (NUS Medicine) in a session moderated by Singapore’s former attorney-general V. K. Rajah.

Her recent visit to Singapore was Dr Ang’s third since she left for Britain in 1977. Her first was in 2012, when she was issued special travel papers to return with her husband’s ashes after he died from a sudden heart attack; her second was in 2020, to attend a commission of inquiry regarding her holding both British and Singapore citizenships, which is not allowed here. Her dual citizenship was the reason she could not return to attend the award ceremony when she was inducted into the Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame by the Singapore Council of Women’s Organisations in 2016.

At the commission of inquiry, she was asked to renounce one citizenship, which she refused to. Giving up her British passport, she says, would have meant losing her right to live and work in the country.

“I also told (the officers) ‘I promised my husband I would never give up my Singapore citizenship, so I won’t’,” she recalls, adding that she harbours no resentment for when she was officially stripped of her citizenship on 11 November 2020.

“I cannot fault the Government here. How can it answer to the rest of the country by allowing me to hold dual citizenship? They’ve kept it open for me for so long, and I’m very appreciative,” she says, sitting in the living room of her sister-in-law’s home in the Bukit Timah area.

Wearing a shawl because chemotherapy has made her lose her hair, Dr Ang still speaks with a strong Singapore accent despite having spent nearly half a century in Britain.

She is the eldest of 4 children. Her mother was a teacher who became a resistance fighter during the Japanese Occupation; her father was a journalist who also opposed the Japanese Army. Both were imprisoned and met when they were released after the war.

Dr Ang was born in Penang where her maternal grandparents lived, but moved to Singapore before she started school. For several years, home was a rented room in a shophouse in River Valley Road. Her father juggled two jobs—doing administrative work for trading company Lim Teck Lee by day, and editing the commodities pages of Chinese daily Sin Chew Jit Poh at night—to make ends meet.

A self-starter, the former Raffles Girls’ School student studied Medicine at the then University of Singapore because “my parents said we should live to serve our fellow human beings”.

Dr Ang in a 2009 photo with children at Martyr’s Square in the Shatila refugee camp where nearly 1,000 victims of the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre by the Israel-backed Lebanese Phalangist militia were buried. PHOTO: ANG SWEE CHAI

“On the first day, we had to go into the dissection room. There were dead bodies and we were supposed to cut these cadavers. Two boys fainted,” she recalls. “I went home and told my mother: ‘I’m not going to do this. I’m going to be a teacher’.”

Her father told her she could do what she liked as long as she paid him back the $500 he had already shelled out for her first term. She sheepishly went back to medical school the next day.

She graduated in 1973 with a silver medal, and got her master degree—and a gold medal—in public health and community health medicine 3 years later. She harboured grand plans of “doing good on a big scale”—influencing policies on vaccination, nutrition and occupational health—but was deemed too “hot-headed” for a job in public health.

So she returned to clinical medicine and did her Fellowship of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons to become an orthopaedic surgeon.

“I love surgery because it’s very hands-on. If it works, your patient is cured and his lifestyle is improved. If you get it wrong, you get sued,” she quips.

One of her mentors when she was a young surgeon was Dr Kanwaljit Soin, Singapore’s first female orthopaedic surgeon and first female Nominated Member of Parliament.

Now 82, Dr Soin remembers her well: “She was such a hard-working eager beaver who was very conscientious and wanted to know everything.

“I’m proud of how far she has come. She’s a real heroine. In my next life, I want to be like her.”

On track to become a star surgeon, the young Dr Ang didn’t know her life would soon turn topsy-turvy when she met Mr Khoo at a gathering. He passed her the book Pedagogy Of The Oppressed—a classic text on critical pedagogy—by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Not long after, she read in The Straits Times that Mr Khoo was the defence lawyer in a trial involving shipbuilding workers and a student leader charged with rioting.

“I phoned him and said: ‘Francis, are you sure you want to do this?’ He replied: ‘I’m a lawyer, I’m able to defend these people who have got no money. I’ve got to give them justice’,” she says of Mr Khoo who, among other things, also opposed Singapore’s abolition of the jury system and the 1972 Christmas Day bombing of Hanoi by the US.

In 1977, she asked him to marry her.

“I told him: ‘If you actually end up in prison, I cannot visit you. I have no standing. At least make me your wife’,” she recalls.

Barely a few weeks into their marriage, he fled for England. Not long after, while she was performing an operation at Singapore General Hospital, the ISD came for her. She made them wait until she completed her operation. She was taken in for interrogation, and released after promising she would persuade her husband to return.

She flew to London, and remained with Mr Khoo, who became a political refugee.

“How can I, just for the sake of a career and a secure home, leave my husband? That’s not me. I’ve got to stand by my man.”

She had to restart her medical career from the bottom up, fighting discrimination, racism and sexism—“accent not right, face and size don’t fit”—along the way. “I worked in about 40 different hospitals, sometimes on a 6-month contract.”

One evening in 1982, just when her career was finally on track, she saw on TV footage of the Lebanon war. Although she was then a Zionist Christian who was pro-Israel, she was upset that the Israeli invasion of Lebanon had resulted in the homelessness and deaths of thousands.

She resigned from St Thomas’ Hospital to answer—with the blessings of her husband—an international SOS for an orthopaedic surgeon to treat the injured in Beirut. There, she discovered that the carnage and destruction had been many times worse than what she saw on TV.

“You cannot say you are conducting a war against a bunch of terrorists when you seek out civilians and kill them, destroy homes, schools, factories, universities and then displace thousands of people so that they have no home to go to and call it a military operation for peace,” she said in her speech at the HCS dinner.

Treating mangled limbs and horrific wounds she could cope with.

“I’m trained to deal with bloodshed, fractures and human flesh. When I was operating, it was okay, I was doing a technical job,” she says.

The hundreds of corpses—all with cards identifying them as Palestinian refugees, not terrorists—she saw outside the hospital was another story.

The horrors of 1982 she witnessed are now being repeated in Gaza, albeit many times worse, she says. “It makes me cry every day.”

However, despairing and wringing hands over the situation will not do, she says. “The challenge is: ‘What are you going to do about it?’”

She lauds the Singapore Government for ordering the Israeli embassy here to delete an incendiary social media post in March, and is impressed that the Rahmatan Lil Alamin Foundation charity has raised more than US$6 million (S$8 million) for the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East.

Several days after this interview, Dr Ang sent me a text describing horrific footage she had seen on TV of Gazans being shot by snipers as they try to collect air-dropped food.

“There is so much to be angry and bitter about. But I thought of the Singapore Armed Forces participating in airdrops of food as well, and I thank God for their efforts. No matter what evil befalls, we will not become cynical.

“We will tell Gaza we will not despair, and we will fight for them to live, and have full-blown human rights.”

More from this issue