Issue 49

Feb 2024

THE LAST MILE

By DR NOREEN CHAN, HEAD AND SENIOR CONSULTANT, DIVISION OF PALLIATIVE MEDICINE, NATIONAL UNIVERSITY CANCER INSTITUTE, SINGAPOREBy Dr Noreen Chan, Senior Consultant and Head, Division of Palliative Medicine, National University Cancer Institute, Singapore

Some years ago, I had written an article about how caring for dying patients and families had taught me so much that cannot be found in textbooks.

It was only possible to give a few examples to illustrate that the work we do in Palliative care is both art and science, and while it can be challenging work, it is also immensely rewarding. Not just the chance to witness the rich tapestry of the human condition, but to develop a healthy respect for the mystery of our existence, how not everything can be explained (nor needs to be).

And so, let me share a few more stories about patients whom I have been privileged to care for, and the lessons imparted:

Is it a wish, or is it a goal?

Twenty years ago, when I was based at Dover Park Hospice, a man was admitted with paralysis from cancer that had invaded his spine. He could only sit up upright for brief periods because his spine was too unstable to support his torso, so he spent most of his time in bed or in a reclining wheelchair. One day at the team meeting, his case was brought up for discussion because the staff were concerned about his ability to cope with his illness. “He keeps talking about going on a cruise next year” … “he told me he would soon go ballroom dancing again” … yet we all knew he would not live longer than a few months. “He’s in denial!” was the team’s consensus.

So, I sat with him and we talked; mostly he talked and I listened, about his life before cancer, what he had enjoyed doing, what he still hoped to do. He had been saving for a trip to Machu Picchu, and had done a lot of reading and research about it. I responded with “Wow that sounds amazing, a dream holiday…” and he broke in with, “I think maybe it will just be a dream…” and became pensive. Subsequently I learnt that he knew exactly what was going on with his body, and his talking about these so-called unrealistic plans was just wishful thinking aloud. What he wanted from us was to acknowledge his right to have big dreams and grand plans, even if they were not going to come true.

He taught me that we must know the difference between a wish and a goal. That it is alright to dream. And that denial is sometimes a defense mechanism so we can wake up in the morning and face the day.

It’s not so much the days in your life, as the life in your days

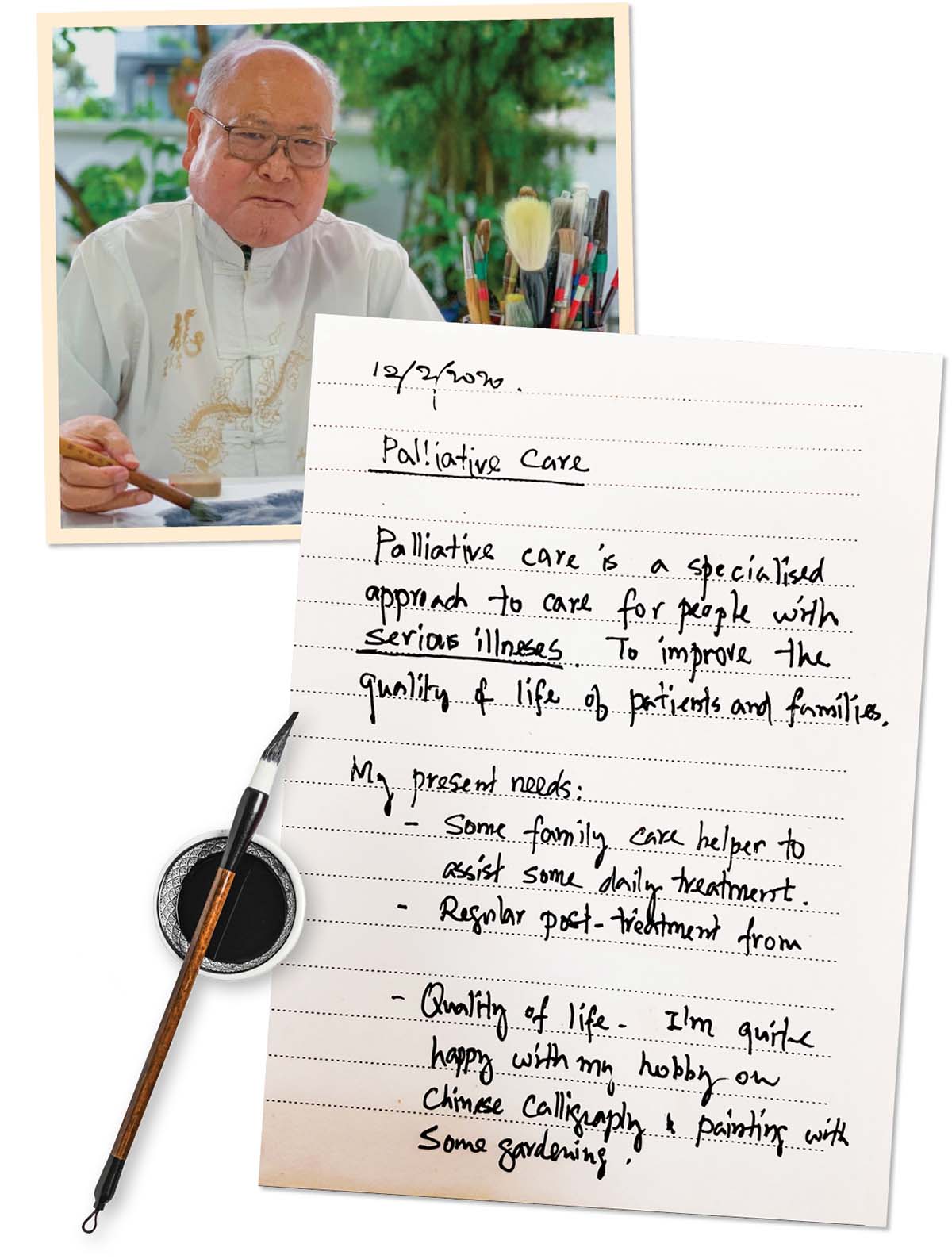

Mr Lee could not speak as a result of his cancer, but he had no problem communicating and connecting with others. He arrived at my clinic for the first time with a pre-written note about his thoughts on palliative care and what he considered to be quality of life, which for him meant a degree of independence and being able to indulge in his hobbies, especially Chinese painting and calligraphy. I had referred him to HCA Hospice Care so that he could be supported at home, and they helped him to arrange an exhibition of his work.

Top-left: Image of Mr Lee How Son, taken from HCA Hospice’s Instagram page, 5 December 2020.

Bottom-right: Mr Lee How Son’s notes.

D was a 19-year-old young man with a brain cancer which had affected his speech and ability to walk. Yet his dream was to finish his ‘A’ Levels, especially English and Mathematics which were his favourite subjects. It was questionable if he could take even one subject, let alone two, but it did not stop the medical team and his school from trying to get him closer to his goal, even if it meant him taking the examination in hospital or at home, with an individual invigilator and extra time to accommodate his disabilities.

It is easy to forget that people with life-limiting illness still wish to experience the richness of life. An older person might be delighted by a celebration of a life well lived, such as an exhibition, photo diary, recipe book etc. But for a young person, a different approach might be needed, for example working towards important milestones of growing up (graduation, National Service etc.). It might not be possible to reach the destination, but the journey still matters.

Being grateful for the little things

J was 23 years old and had been in hospital for a few months, but his aggressive leukaemia was not responding to treatment. He was a big Transformers fan and was hoping to live long enough to watch the latest film when it was released. Due to complications of his disease, he was confined to bed most of the time. When the Haematology team learnt of this, they managed to arrange for a special screening of the film, as well as an outing to Resorts World Sentosa to experience the newly opened Transformers Ride.

It is ironic, then, that acknowledging death may actually help us to have a more fulfilling life. If nothing else, it can help us prioritise how we want to live well, before leaving well.”

It was a major logistic exercise because J needed medical and nursing escorts, ambulance, wheelchair etc., but the ward staff put together a team of volunteers to accompany him throughout (with tickets to RWS sponsored by the senior doctors). You might have thought that the exciting lineup of events at Sentosa would be the highlight of his day, but when he was pushed out of the hospital to the ambulance, he looked up from his stretcher, beamed and said excitedly “I can see the sky!”.

J did not have immediate family, only an elderly aunt, so the hospital ward was his home and the ward staff his family. Despite his difficult circumstances he remained upbeat, open and generous. His farewell message on his Facebook page and to the ward was “Try to stay happy. There’ll be cloudy days, but one day the sun will come out. Just like the time I had here”.

Sometimes you are exactly who and where you need to be

Another story from my time at Dover Park Hospice: One night, I had come back to the hospice on call, and while I was seated at the nurses’ station writing up my notes, a young man approached me from one of the rooms opposite. I guessed that he was a relative keeping vigil because those rooms were reserved for dying patients.

He asked how we know when someone is going to take his last breath. I told him some basic information but also asked him why he was asking. He explained that it was his father who was dying, and as he was the only child, his aunts and uncles had instructed that at the last breath, he had to kneel and call his father’s name. He had been camping at the bedside day and night wondering when the moment would come.

I told him we never really know when the exact moment will be, but since I was already there, I offered to do a quick check just to make sure his father was comfortable. As I was doing my examination, I suddenly noticed out of the corner of my eye that the patient’s breathing was starting to change. “Oh, I think it is happening” I said, and together, we stood and watched over the next few minutes as the breathing slowed and then stopped. I looked at the young man “that was his last breath, he’s passed on” and after the briefest of pauses, he dropped to his knees, called out “Ah Pa” and began to weep.

To this day, I wonder at the chain of events that needed to happen to bring me to the bedside of this dying man, so that his son did not have to be alone. The experience taught me that the universe does work in mysterious ways, and you will never know when and how you can be of service to another, except to be open to the possibility.

Finally

The knowledge that we will not live forever, the acknowledgement of finitude as part of the human condition, has contributed much to the arts, religion and philosophy. It also affects how we approach our own existence, if we actually stop to think about it. Realistically though, most times we do not, and just carry on as if life will always be this way. Paulo Coelho, in his book “Like the Flowing River”, writes about the contradiction of people—“They live as if they will never die, and die as if they have never lived”.

It is ironic, then, that acknowledging death may actually help us to have a more fulfilling life. If nothing else, it can help us prioritise how we want to live well, before leaving well.

To Bless the Space Between Us

For Death

From the moment you were born,

Your death has walked beside you.

Though it seldom shows its face,

You still feel its empty touch

When fear invades your life,

Or what you love is lost

Or inner damage is incurred.

Yet when destiny draws you

Into these spaces of poverty

And your heart stays generous

Until some door opens into the light,

You are quietly befriending your death;

So that you will have no need to fear

When your time comes to turn and leave.

That the silent presence of your death

Would call your life to attention

Wake you up to how scarce your time is

And to the urgency to become free

And equal to the call of your destiny.

That you would gather yourself

And decide carefully

How you now can live

The life you would love

To look back on

From your deathbed.

More from this issue

PEOPLE OF NUS MEDICINE

Understanding Disaster Medicine