Our academics have outdone themselves in research efforts while also contributing to national and international efforts on COVID-19. Taking advantage of new flexible work arrangements, our people have had the opportunity to rediscover and develop themselves with various online learning initiatives. Overall, the School has done well and improved our international standing despite the turbulence and headwinds of 2021, placed at 21st place globally in the Quacquarelli Symonds 2021/2022 ranking of medical schools around the world, while the Times Higher Education ranking listed NUS Medicine at 17th for 2022. This drive to live up to the values of the School, to serve with unstinting grace against the odds, traces its DNA to those who laid the foundations for the School. Some died doing just that, even before they could graduate.

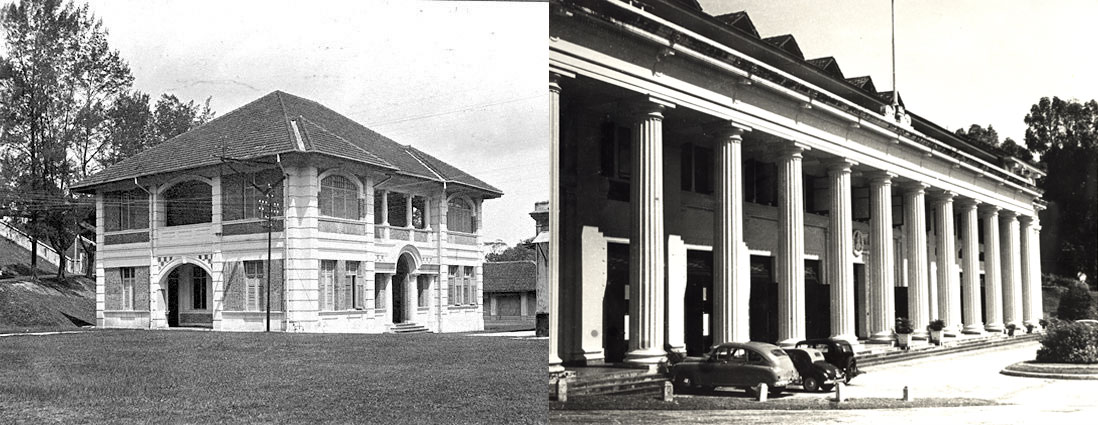

Remembering the pioneers

On the grounds of the Singapore General Hospital stands a modest memorial to a group of medical and dental students who lost their lives to enemy fire in February 1942 during World War II. The events that led to their deaths is recounted in an absorbing article by a classmate, Dr Abdul Wahab.4 In any retelling of the history of the NUS medical school, the names of the 11 students who died should be remembered:

|

1.

|

Yoong Tat Sin

|

|

2.

|

Mabel Luther

|

|

3.

|

N.P. Sarathee

|

|

4.

|

E. Baptist

|

|

5.

|

H.E. Oorjithan

|

|

6.

|

Ling Ding Ee

|

|

7.

|

Hera Singh Bul

|

|

8.

|

Chan Kok Loon

|

|

9.

|

Chen Kok Kuang

|

|

10.

|

Teoh Tiaw Teong

|

|

11.

|

Abdul Hamid Bin Mohd Yusoff

|

While the ultimate sacrifice of these students in service to their fellow men has thankfully not been repeated since that fateful day in 1942, the spirit of service that energised them lives on in NUS Medicine alumni, as well as staff and students of the School today.

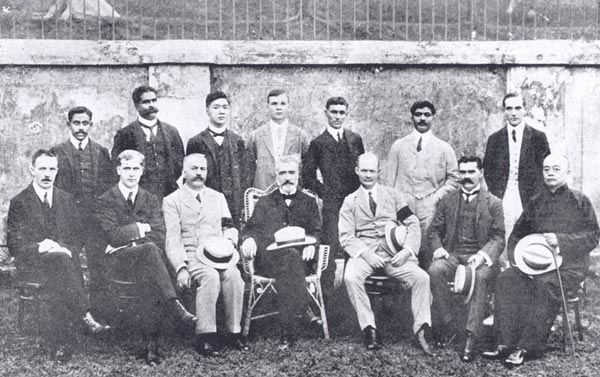

First cohort of students in 1910 pioneer group standing behind teachers.

No pandemia here

It is seen for example in the creative approaches that were adopted to circumvent the interruptions to daily life brought about by the pandemic: student-hopefuls applying for a place were assessed differently. Where previously 1,000 candidates would put pen to paper at the University for their Situational Judgement Test, applicants in 2021 did this from the comfort of their homes—an online assessment, recorded for integrity, was held instead. The Focused Skills Assessment component of our admissions exercise, however, remained on-site. These tests, comprising role play, task-based components, group work, and interview stations, are vital to ensure students not only have an aptitude for medical studies but also hold values aligned with those of the School.

Our teaching staff too did not let teaching and learning come to a halt. Despite constraints such as a limited group size of five for bedside teaching—including patient, students, tutors, and other healthcare workers—and embargos on high-risk areas, students still benefited from the School’s creative pedagogy. For example, the School’s digital transformation journey progressed with even more cyber tools rolled out for our tech-savvy students.

The Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G) and the Department of Anatomy—both of which celebrate centennials this year—have embedded virtual reality into their curriculum, adding to the suite of technologies and online learning platforms that had been introduced earlier. At the O&G Department, a simulated labour ward expands students’ clinical exposure beyond what they would otherwise receive in a six-week posting. Students are taken through a range of cases in the second and third stages of labour, via professionally animated videos on all blueprint topics and annotated surgical videos with commentaries. Each step is guided and every rationale explained, for common obstetric and gynaecological surgeries. Interactive presentations aid students as they take on the role of house officers, brainstorming patient management plans under various scenarios. Likewise, students learn about anatomy and physiology through 3D virtual learning technologies that even allow them to try their hands at virtual dissections, while instruction using cadaveric specimens provides critical understanding of the three-dimensional relationship of different anatomical structures and their variations.

Students using Hololens.

Examinations however, continued to be observed along national guidelines. They were held on campus, away from healthcare institutions. For theory assessments, additional measures included a maximum of 50 persons to an exam room, visual identity verification software, and staggered reporting times. For clinical examinations, supplementary measures comprised pre-event testing, staggered reporting, and cohorting. The use of real patients was re-instituted at certain stations.

In a feature article in the Singapore Medical Association, new house officers Dr Isaac Ng, Dr Valencia Zhang, Dr Tseng Fan Shuen, and Dr Desiree Tay described their final MBBS examinations as “a surreal experience”. Struggling to deal with the uncertainties thrown up by the pandemic, they were yet well prepared, noting, “In NUS Medicine, we are privileged to have access to comprehensive e-learning resources (as well as) virtual scenario-based clinical teaching.” They also shared that though batch-mates had significant worries, “We were extremely appreciative of the School’s efforts to provide regular updates through multiple online platforms … In addition, our clinical tutors held regular virtual townhalls to provide an avenue for students to voice their concerns.” The cohort has since passed a milestone. While the Commencement Ceremony for the Classes of 2020 and 2021 was first held virtually in July, Commencement for the Class of 2022 reverted to the traditional ceremony held on campus in July this year.

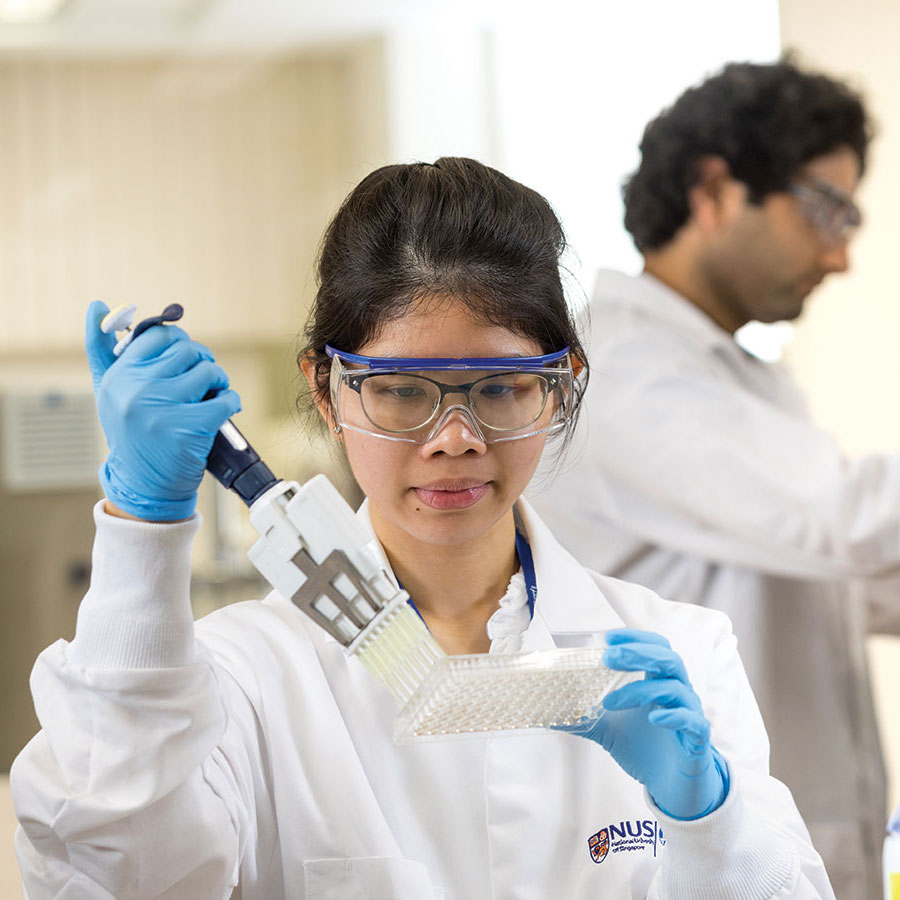

Translating biomedical findings to clinical practice

While the NUS medical school’s founding mission was to educate and train doctors for the community, the pivotal role of biomedical research has always formed the other raison d’etre for our work. Research at NUS Medicine focuses on finding solutions to diseases that afflict the Singaporean population, and aims to ultimately enhance people’s overall health and well-being.

With this in mind, the School reorganised its research structure into Translational Research Programmes (TRPs) in 2019 to promote interdisciplinary collaboration and cross-pollination of ideas. Strategically selected to meet the current and future healthcare needs of our population, our 10 TRPs focus on health matters relevant to Singapore, other Asian communities in the region, and beyond. Each of our TRPs is directed by a lead scientist and a clinical lead who manage the core funding for the programme to attract expertise and develop research facilities. With an interdisciplinary focus, our TRPs enhance collaboration and synergy to maximise limited resources. Research is also given the space to evolve to meet changing needs. Let me share a few key examples of our work.