Issue 45

Jan 2023

A WORLD IN A GRAIN OF SAND

BY Associate Professor Kevin SW TAN, Head, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, and Vice-Dean for Graduate Studies, NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

Among the various themes of the English poet William Blake’s ‘Auguries of Innocence’, recognising the fragile beauty and balance found within nature resonates with the microbiologist in me.

The first sentence of his poem, ‘To see the world in a grain of sand’ reminds us that there is depth and beauty in mundane objects, if one would only stop to ponder on its many dimensions. I am pleased to write the inaugural article in this series with the theme ‘The world in a grain of sand’. In the coming issues, my colleagues from the Department of Microbiology and Immunology will bring you into a wondrous world of microbes and immunity. They will share their insights as experts in their domains of research and education, and perhaps help us appreciate this microscopic world, its complexities, and the secrets it can reveal if only one stops to wonder, and ruminate.

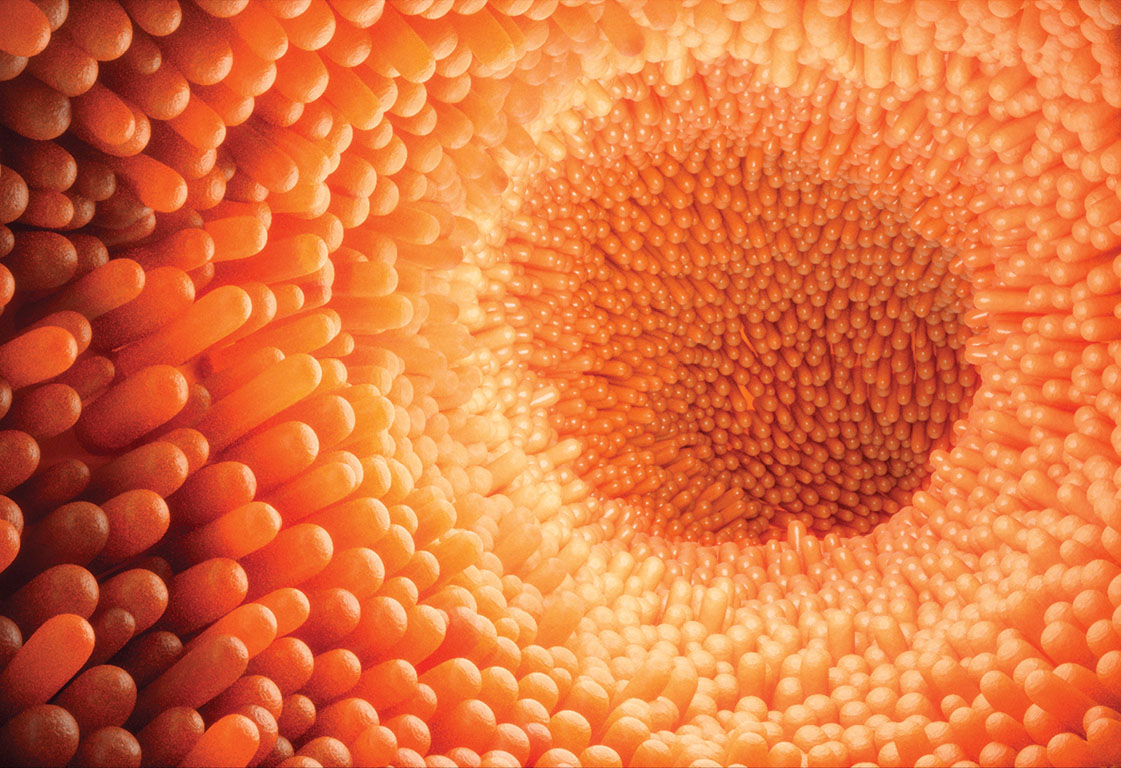

The magnificent microflora of the gut

Once thought to be distinct from our own tissues and organs, the trillions of bacteria that reside in our gut have, in recent decades, been acknowledged to constitute a core component of our physiology and are not mere tummy travellers. These are collectively called microbiota and comprise over a thousand species of bacteria that, in a healthy individual, play vital roles in digestion, metabolism, gut health and immunity.

The gut is also connected to our central nervous system through the vagus nerve, and the microbiota regulates the production of molecules that affect mood and behaviours (that’s why balanced diets can promote happy feelings). New sequencing technologies have unravelled some interesting characteristics of this collection of bacteria. A key observation is that a healthy gut would be made up of many different bacteria gene sequences, indicating that many microbes reside there. This genetic diversity allows the bacteria to perform a bewildering array of physiological functions, with each function often being fulfilled by more than one group of bacteria. When this balance is disturbed, either through stress, cancer or some other undesirable stimuli, this diversity is lost, and often, certain disease-promoting groups of bacteria flourish. These pathogens can cause gut diseases directly, or through the loss of collective metabolic functions afforded by the microbiota. Blake would have appreciated that microbial balance and diversity are important requisites for gut health!

Enter the ecosystem engineer

Bacteria are not the only microbial inhabitants of the human gut. There exists a much smaller faction of a physically larger, yet often overlooked group, called the single cell eukaryotes, or SCEs. These comprise yeasts (think Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and protists, such as amoebas and flagellates. Our laboratory has in recent years investigated the role of Blastocystis, a common SCE of the gut. Fortuitously, we keep a collection of various genetic types (called subtypes, or STs) in our laboratory which allows for the study of microbiome changes using laboratory models of colonisation. Blastocystis ST7, which is common in Singapore and the region, was associated with a loss of bacterial diversity in hospital patients suffering from diarrhoea. In laboratory models, Blastocystis ST7 killed off good bacteria, promoted pathogen growth, caused loss of diversity, which in turn led to an increase in inflammatory cells under the gut lining and decrease of short-chain fatty acids (healthy metabolites produced by bacteria). Worryingly, when laboratory models were induced to undergo gut inflammation, adding ST7 exacerbated the disease.

In the West, a different, yet microscopically indistinguishable, ST is prevalent. ST4 is the most common ST in Europe and North America. Oddly, from microbiome surveys in Europeans, ST4 carriers had higher microbiome diversity, and by extension, better gut health, compared to non-carriers. We reproduced these findings in laboratory models and showed that introducing ST4 into laboratory models resulted in greater microbiome diversity and increased production of beneficial metabolites. Startlingly, in colitis (gut inflammation) models of disease, adding ST4 accelerated recovery, dampened inflammation, promoted beneficial bacteria growth and kept the numbers of disease-promoting bacteria at bay. ST4, in essence, behaves like a probiotic, enhancing gut health.

Upon rumination, one can glean several insights from these studies. Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 look identical, are genetically similar, yet have striking, and opposing effects on the gut. In a recent major study, a side-by-side comparison of these two STs in laboratory models of colonisation confirms that ST4 behaves like a health supplement while ST7 is clearly toxic to the microbiota ecosystem.

Can the Blastocystis-Microbiota relationship reveal leadership lessons?

When I reflect on my seven years serving in the Dean’s Office, first as Assistant Dean, and subsequently as Vice-Dean, and the last two years as Head of Department, I wonder if I relish stress and suffering! Or does the opportunity to improve the lives of others in my community outweigh the punishing cost (and sacrifice) of administrative service? In preparing for this article, I decided to share my reflections of what constitutes effective leadership, but at the intersection of research and service, with a focus on the humble and beneficial protist, Blastocystis ST4.

|

1. |

Like ST4’s influence on the gut microbiome, effective leaders promote diversity in their workplace, hire team players and create a resilient environment, that can weather challenging periods. Diversity allows for complementary skill sets to coexist, promotes collegiality, and increases well-being within the community. |

|

2. |

ST4 is considered an understudied, neglected parasite (which is an inaccurate label) by the general scientific and clinical community. Yet it is clear that it engineers the microbiome in a positive manner. Effective leaders shun the limelight but use their skills to empower and enable teams. Such teams inevitably produce good outcomes (good metabolites) and positively impact the School (host). |

|

3. |

Effective leaders are agile and react quickly to solve problems, whenever these arise, no matter if difficult decisions need to be made. In laboratory models that were triggered to undergo gut inflammation, the administration of ST4 resolved the disease quicker, through multiple mechanisms. Conversely, priming the gut with ST4, created a resilient microbial ecosystem that could mitigate the effects of toxic colitis triggers (see 1). |

So, let’s flip the switch and use Blastocystis ST7’s impact on the microbiome as an analogy for ineffective leadership.

|

4. |

Poor leaders suppress good staff and promote those who are under-performing. This dampens morale and creates a toxic environment in which those with the wrong priorities thrive. Similarly, ST7 kills good bacteria, promotes the growth of pathogens and results in dysbiosis (loss of microbiome balance). |

|

5. |

Blastocystis ST7 produces molecules that damage the integrity of host tissues, and sometimes, kills the laboratory model in which it was introduced. In the same vein, poor leaders can cause direct damage to the teams through acts of commission and omission, or simply through demeaning and discouraging words. In extreme cases, they leave the organisation in shambles when they move to their next posting (or get promoted!). |

|

6. |

In colitis models, inoculating ST7 exacerbates the disease, likely through mechanisms described above. This results in severe inflammation and pathology. Whether through inexperience or inability, toxic leadership often turns a bad situation into a calamity. This can occur through many means, such as playing the blame game, through inaction, or incompetence (think how the leaders of some countries have managed, or mis-managed their handling of the COVID crisis). |

These stories have implications for senior management. Both ST4 and ST7 are microscopically indistinguishable yet exert beneficial or toxic effects on the host. Likewise, it is profoundly difficult to decide if someone will be a good leader based on superficial measures (CVs, interviews, even reference letters), yet they can have such a major impact on the culture and outcomes of the teams they lead. Hence, the wrong decision results in appointments that produce major, negative impact on the morale, culture and outcomes upon the teams that they lead. Taking a page from this article, an effective way may be to survey the former subordinates of the candidate (checking the health of the microbiome). It may be a difficult pill to swallow, but honest brutal feedback on a potential candidate may save your institution from future damage, collateral or otherwise.

After more than 25 years in this wonderful institution I call my second home, I have the benefit of hindsight. Juxtaposing the unlikely worlds of Blastocystis research and administrative service has helped craft a certain philosophy to leading teams—empower and enable others, promote the deserving, create a positive and supportive work culture, and manage crises and achievements away from the limelight. It’s amazing how much a ‘grain of sand’ can teach us!

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/gut-feelings-how-food-affects-your-mood-2018120715548.

Tito RY, Chaffron S, Caenepeel C, Lima-Mendez G, Wang J, Vieira-Silva S, Falony G, Hildebrand F, Darzi Y, Rymenans L, Verspecht C, Bork P, Vermeire S, Joossens M, Raes J (2019) Population-level analysis of Blastocystis subtype prevalence and variation in the human gut microbiota. Gut 68:1180-89.

Deng L, Wojciech L, Png CW, Kioh DYQ, Gu YX, Aung TT, Malleret B, Chan ECY, Peng G, Zhang YL, Gascoigne NRJ, Tan KSW (2023) Colonization with two different Blastocystis subtypes in DSS-induced colitis mice is associated with strikingly different microbiome and pathological features. Theranostics doi:10.7150/thno.81583

Deng L, Lee JWJ, Tan KSW (2022) Infection with the pathogenic Blastocystis ST7 is associated with decreased bacterial diversity and altered gut microbiome profiles in diarrheal patients. Parasites Vectors 15:312.

Deng L, Wojciech L, Png CW, Koh EYL, Aung TT, Kioh DYQ, Chan ECY, Malleret B, Zhang YL, Peng G, Gascoigne NRJ, Tan KSW (2022) Experimental colonization with Blastocystis ST4 is associated with protective immune responses and modulation of gut microbiome in a DSS-induced colitis model. Cell. Mol. Life Science. 79: 245.

Deng L, Tan KSW (2022) Interactions between Blastocystis subtype ST4 and gut microbiota in vitro. Parasites Vectors 15:80.

Deng L, Wojciech L, Gascoigne NRJ, Peng G, Tan KSW (2021) New insights into the interactions between Blastocystis, the gut microbiota, and host immunity. PLoS Pathog 17(2): e1009253.

More from this issue