Issue 44

Nov 2022

INSIGHTS

BY DR VOLKER PATZEL, SENIOR LECTURER, DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND IMMUNOLOGY

I grew up in Germany and discovered my passion for science as a young child. At the age of 12, I made the decision to study chemistry, which I then did many years later. I specialised in biochemistry and went on to do a PhD in biomedical research.

It was then when I became fascinated by the idea that the technologies we develop in the laboratory could eventually benefit patients in the future.

After having co-founded a biomedical start-up, I realised that moving towards research work that could benefit patients requires an additional skill set, which was why I pursued an executive Master of Business Administration (MBA) as well. Doing an MBA as a scientist turned out to be a great personal gain, and retrospectively, I value the network of like-minded classmates and friends much more than the imparted knowledge.

The completion of my education and training kindled in me the desire to share my knowledge and to educate the younger generation.

At the end of 2009, I joined NUS which was, on one hand, a great opportunity to conduct independent research, and on the other, for building up my own teaching portfolio. Today, I am coordinating six modules, teaching both undergraduate and graduate students, as well as lifelong learners in biomedical sciences, bio-innovation and entrepreneurship.

When I started teaching at NUS, I realised that the education system differs from the one in my home country, as well as the way students and teachers interact with one another.

In Germany, students have no qualms in approaching me with questions, whereas in Asia, it is not common for students to do so. This made receiving sufficient classroom feedback very trying. Classroom feedback is an aspect I have always deemed essential, in order to facilitate self-regulation and assessment for both student and teacher performance. Effective intervention has to be done before students receive their examination results, and before gathering the end-of-semester feedback.

Indubitably, the lack of pro-activity from my students started to get to me, and I doubted myself as a teacher—until colleagues shared similar issues.

“I hypothesised and hoped that a classroom feedback system would help promote assessment and self-assessment of student and teacher performance, to improve both the quality of teaching and my students’ performance.”

At that time, I joined the Professional Development Programme Teaching (PDP-T) at NUS, which introduced the concept of technology-supported student feedback systems to me. I greatly welcomed the idea of giving students the opportunity to provide anonymised feedback, and hence decided to implement a technology-supported student feedback system into my modules.

I hypothesised and hoped that a classroom feedback system would help promote assessment and self-assessment of student and teacher performance, to improve both the quality of teaching and my students’ performance.

Initially, as a classroom response system, I selected clickers, and later switched to Poll Everywhere. I decided to set up a classroom feedback system that included three sessions of multiple-choice (MCQ) quizzes spread over the course of each module, with each session comprising two identical rounds of questions together with a lecture1.

In the first round, students were asked to respond immediately, while in the second round, they were encouraged to first discuss their responses with their classmates. Both peer instruction and repeated testing had been reported to facilitate a deeper comprehension and actively build knowledge2,3.

All in all, this setup provided the students with three different levels of feedback. First, the externally observable outcome of each MCQ session supplied the students with direct computerised quantitative feedback.

Second, the critical dialogue with peers prior to submitting the answers for each second round gave them dialogical external feedback. Finally, I could bring forth qualitative external feedback, through facilitated in-class analyses and discussions.

Furthermore, this three-stage classroom feedback system also helped me to gauge the students’ level of understanding, as it identifies both areas of difficulty and confusion, as well as areas of interest. This feedback has enabled me to shape the sequel to the module, “Fostering Audience-paced Instruction”, thereby indirectly providing the students with additional external feedback.

“This technology-supported three-stage classroom feedback system was very easy to implement and provided tremendous benefits to my students and myself. I would recommend the implementation of such a system to my colleagues at NUS, in Singapore and abroad.”

In total, I monitored three performance indicators, comprising the percentage of correct and false answers, the percentage of questions answered correctly by all students, and the difference in percentage of correct answers between rounds one and two of each session.

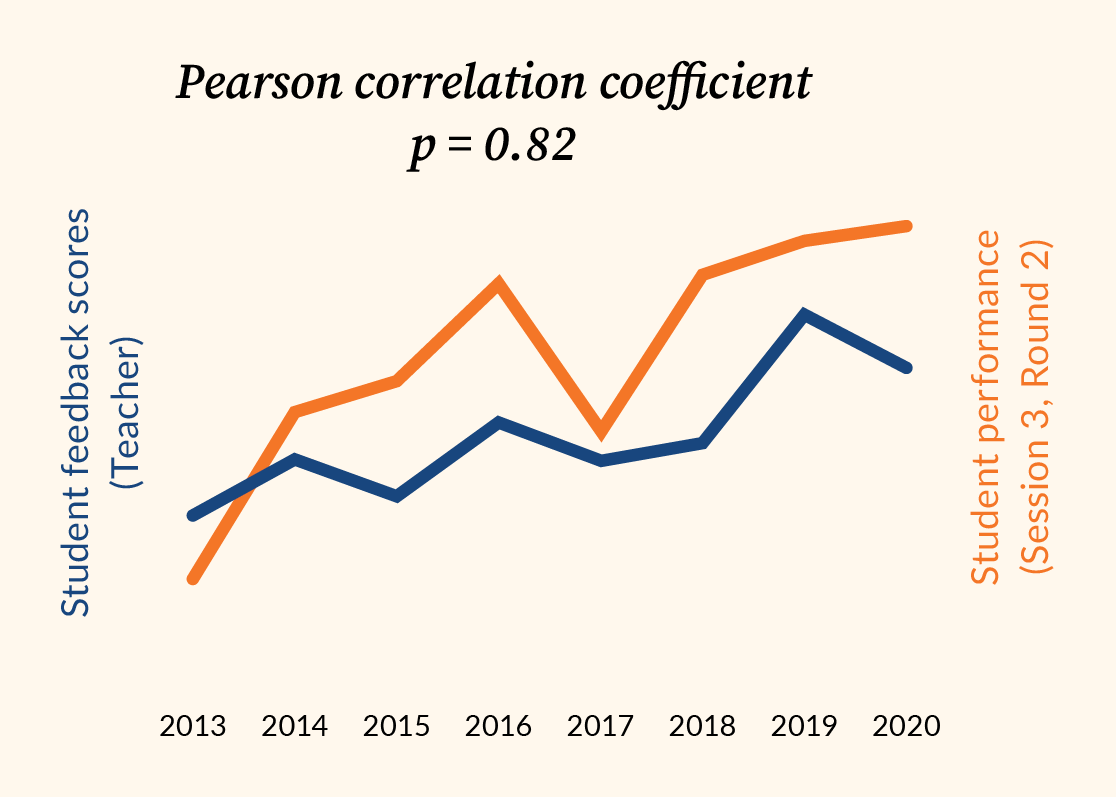

This three-stage classroom feedback system has been implemented in my modules since 2013, and I observe the same tendencies every year.

Firstly, the percentage of correct answers has always increased from the first to the second round of polling, indicating that the dialogical feedback from the peers together with the first-round computerised feedback triggered measurable learner self-regulation.

Secondly, the percentage of correct answers (first and second rounds) as well as the percentage of questions that were answered correctly by all students dropped from MCQ sessions 1 to 3, showing that classroom feedback from the students triggered measurable teacher self-regulation as I steadily raised the level of difficulty for my questions.

Most importantly, the percentage of correct answers at the end of the module rose steadily every year, with the exception of the 2017 batch. This indicates that student and teacher self-regulation sparked an improvement in students’ learning and understanding. In other words, this technology-supported classroom feedback system has helped me to deliver the curriculum more efficiently, and be a better teacher.

As a whole, I also wanted to find out whether increased student performance would lead to greater student satisfaction, including better end of semester student feedback scores for me as a teacher. Not unexpectedly, I found a strong correlation (p=0.82) between the students’ performance at the end of each module and the feedback scores I received (Figure).

Unlike graded continuous or final exams where questions have to be modified every year, the questions in my MCQ quizzes have largely been identical and no grading was performed. Hence, the results obtained using this feedback system are granting rather unbiased insights into the performance of students and teachers.

Currently, I am investigating if the implementation of my classroom feedback system also improved the students’ output during their exams. In addition, we analysed whether the COVID-19 pandemic and the switch between face-to-face (f2f) and online or hybrid teaching formats measurably impacted the students’ performance.

In summary, this technology-supported three-stage classroom feedback system was very easy to implement and provided tremendous benefits to my students and myself. I would recommend the implementation of such a system to my colleagues at NUS, in Singapore and abroad.

Patzel V. Implementation of a Technology-supported Three-stage Classroom Feedback System for Promotion of Self-regulation and Assessment of Student and Teacher Performance. American Journal of Educational Research. 3(4), 446-449, 2015.

Crouch, C.H. and Mazur, E, Peer instruction: Ten years of experience and results, American Journal of Physics, 69(9). 970-977. 2001.

Smith, M.K, Wood, W.B, Adams, W.K, Wieman, C, Knight, J.K, Gulid, N. and Su, T.T, Why peer discussion improves student performance on in-class concept questions, Sciences, 323(5910). 122-124. 2009.

More from this issue