Issue 41 / February 2022

Alumni Voices

Not Forgotten

Moved by the plight of migrant workers caught up in Singapore’s pandemic fight, Dr Tam Wai Jia (MBBS Class of 1987) sought like-minded partners to reach out to the often unseen and forgotten foreigners in our midst who toil away building and tending to Singapore’s infrastructure.

he pandemic has affected all of us, but it has hit some groups harder than others.

Many healthcare workers haven’t been able to take leave in almost two years. And our migrant worker community, too, experienced the most restrictions in terms of their ability to move around freely.

While some of the measures have been eased, the issues facing migrant workers resurfaced in October when workers at a Jurong dormitory were frustrated with the lack of care even as COVID-19 cases started climbing again.

We also know that our migrant workers have been grappling with isolation and loneliness.

Pre-pandemic, our interactions with our migrant worker community were probably few and far between. But right now, it feels like they might as well be from another planet. Their problems seem so big and far away…

Meet My Brother SG

Cometh the hour, cometh the woman—and in this case, a medical alumna of NUS Medicine with an artist’s soul and a heart for the forgotten and the unseen. Moved by the plight of the foreign workers, mother of two, Dr Tam Wai Jia quickly founded My Brother SG and in a short period of time, wove it into a service and outreach network of partners who are passionate about engaging and empowering migrant workers in Singapore.

While that might sound like a broad description, it’s precisely this breadth of ambition that sets My Brother SG apart.

A quick look at its Get Involved page shows volunteer positions from social media management, graphic design and video editing; to translation, volunteer management and befriending.

Initiated by Wai Jia through an international non-profit that she founded—Kitesong Global—and partnered by NUS Medicine, My Brother SG brings together migrant worker-related organisations to ensure a nationally coordinated effort in risk communications and community engagement.

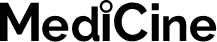

An on-ground health engagement to migrant workers at Penjuru Recreation Centre.

“As the pandemic unfolded, it was, strangely, my work as an artist, that opened the door to work with the migrant worker community,” she said.

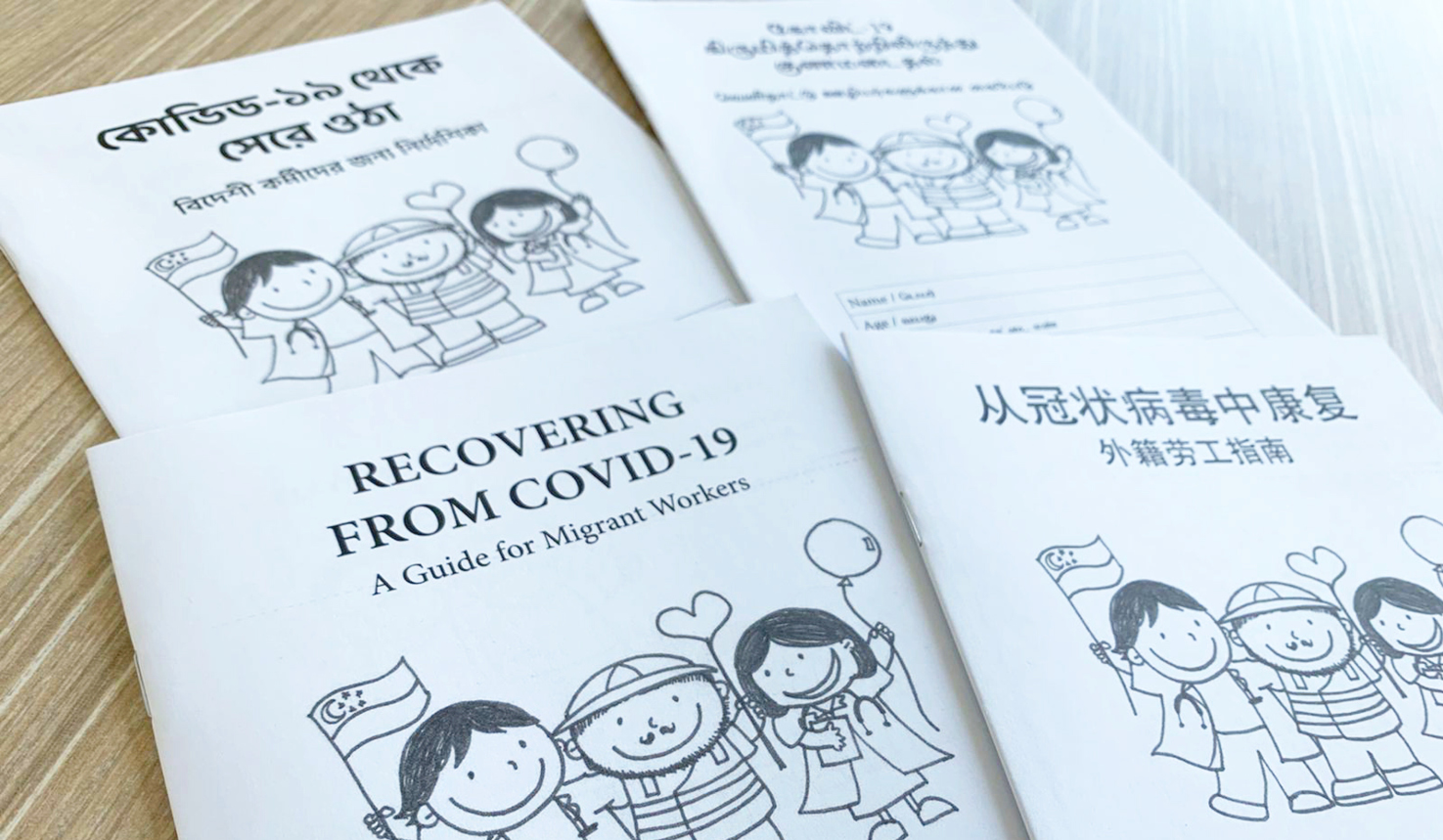

“Many migrant workers were confused by the many new measures that were put in place to slow the spread of the virus, and those admitted to Community Care Facilities were anxious, so I was asked to illustrate an orientation booklet to help with this.”

Wai Jia admits to being initially disappointed by the invitation to help in the outbreak via her gifts in illustration. But little did she foresee that helping the migrant worker community in this way would help marry her gift in art and her public health background to fulfil a long-time dream of hers.

“When I was 17 years old, I had written in my medical school application that I hoped to work with the World Health Organization (WHO) someday. While I was at Johns Hopkins pursing my Masters of Public Health, I desperately sought an opportunity as a doctor. But none presented itself.”

A migrant worker reading a Bengali health booklet, at a participatory health engagement session at his dormitory.

“Because of the booklets, the chairman of the Global Outbreak Alert Response Network, WHO contacted me, showed me a diagram of the key pillars of an outbreak response, pointed to a section called risk communications and community engagement and said, ‘We’ve been lacking this piece of the puzzle and you’re doing exactly it. Let’s work together.’”

And so, along with a growing network of government agencies, healthcare institutions, non-profit organisations and volunteers, My Brother SG was born.

Said Wai Jia, “It was such a great privilege to be able to do this first as a volunteer, and later, with my supervisor’s support, in my professional capacity as Deputy Lead of Global Health & Community Service at NUS Medicine to grow the work. I cannot thank God enough for amazing mentors who fully supported this work.”

Through a research project sponsored by WHO, the team was able to understand the needs on the ground better, which led to a nationwide digital campaign that includes multilingual health booklets, posters, comics, videos and face-to-face engagements for migrant workers.

The committee members currently meet once a month to discuss how they can align strategies to support the health of our migrant workers.

No straightforward solutions

Observing that the morale among migrant workers has been low due to the prolonged lockdown, Wai Jia shared how she had been touched by her interactions with these resilient workers.

“I’m always struck by how grateful they are. Either for the opportunity to work in Singapore or for anyone who shows concern for them, in spite of all the challenges they have faced.

“Even in the situation that they’re in, many of them choose to give of themselves. For example, one of my migrant worker friends, now a health ambassador for My Brother SG, started a Facebook group for his fellow migrant workers. He creates uplifting content for them. And for what? It’s not like he’s earning any money from this. It’s just his desire to give something back. Many of them are amazing like that.”

For young people who feel that they are just on the fringes and watching all of this unfold, Wai Jia wants them to know that there are ways they can help.

“I believe the way forward is to build authentic relationships with migrant workers, recognising that your own gifts are not too small.”

“My dream is to have every dormitory adopted by a community group, every worker to be genuinely befriended by Singaporeans.”

“Because of the booklets, the chairman of the Global Outbreak Alert Response Network, WHO contacted me, showed me a diagram of the key pillars of an outbreak response, pointed to a section called risk communications and community engagement and said, ‘We’ve been lacking this piece of the puzzle and you’re doing exactly it. Let’s work together.”

Dr Tam Wai Jia (MBBS Class of 1987)

They also serve, who toil at the rear

This realisation struck Avelyn Aw, who is helping out with leading My Brother SG’s student core team as well as inducting new volunteers and coordinating translation work.

While she admits that she didn’t always have a clear desire or calling to serve the migrant worker community, she said: “COVID-19 exposed many needs of the migrant brothers and, along with social media, put this vulnerable group in the spotlight.

Health-literate, multilingual health booklets produced by volunteers from Kitesong Global.

“Many individuals and organisations stepped up to help, and I was inspired by the goal of My Brother SG: to synergise the efforts and resources between all these different entities that shared the same heart of serving the migrant worker community.”

As a medical student at NUS Medicine, Avelyn felt that while community service has always been integrated into school curriculum since young, it is easy to grow up thinking that volunteering and service equates to physical exertion and face-to-face interaction with beneficiaries.

“But in My Brother SG, there is a lot of back-end work, and sometimes it doesn’t seem as ‘heroic’ as our doctors and nurses in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) at the dormitories and isolation facilities,” she explained.

“This journey has been humbling because it made me realise that there was pride and selfishness in the way that I was serving and volunteering. I am still learning what it means to genuinely serve and love those around me, and not on my own terms.”

Adds Wai Jia, “If reading about what migrant workers are going through strikes a chord, don’t doubt yourself—head over to My Brother SG’s volunteer page to see how you can get involved.”

An earlier version of this article was first published in thir.st.