Issue 39 / August 2021

People of NUS Medicine

The Eye Surgeon’s Art

The alumnus from the Class of 1994 gives a glimpse into his work with patients with glaucoma and other eye conditions.

octors will tell you that every discipline attracts people with different personalities. As eye surgeons, we are firmly in the camp of the doers. Sometimes we focus too much on the problem at hand—strive for solutions and fix the problem. We tend to focus on that rather than the entire person. I might have been headed that way too, but for a certain twist of fate early on in my career.

I met a Human Resource officer at Ministry of Health when I was a new doctor one day. He asked me what I wanted to do. I jumped at the opportunity, telling him about my grand plans to be a great eye surgeon, save eyes and such. He smiled and said, “But your name is Loon! You should be a psychiatrist!” and honest to goodness, before you know it, I was sent to Woodbridge Hospital in my inaugural posting as a medical officer, where I spent the next six months. Later, during my National Service days, I spent the next two years doing psychiatry. It was not all for nothing mind you: one of the things I learnt was to listen.

And for someone who is objective driven, it may not come as second nature. You learn to listen to your patient for hours on end, then work with the other team members like the occupational therapist, medical social worker and the nursing team to help keep the patient mentally and physically well, and engaged with society.

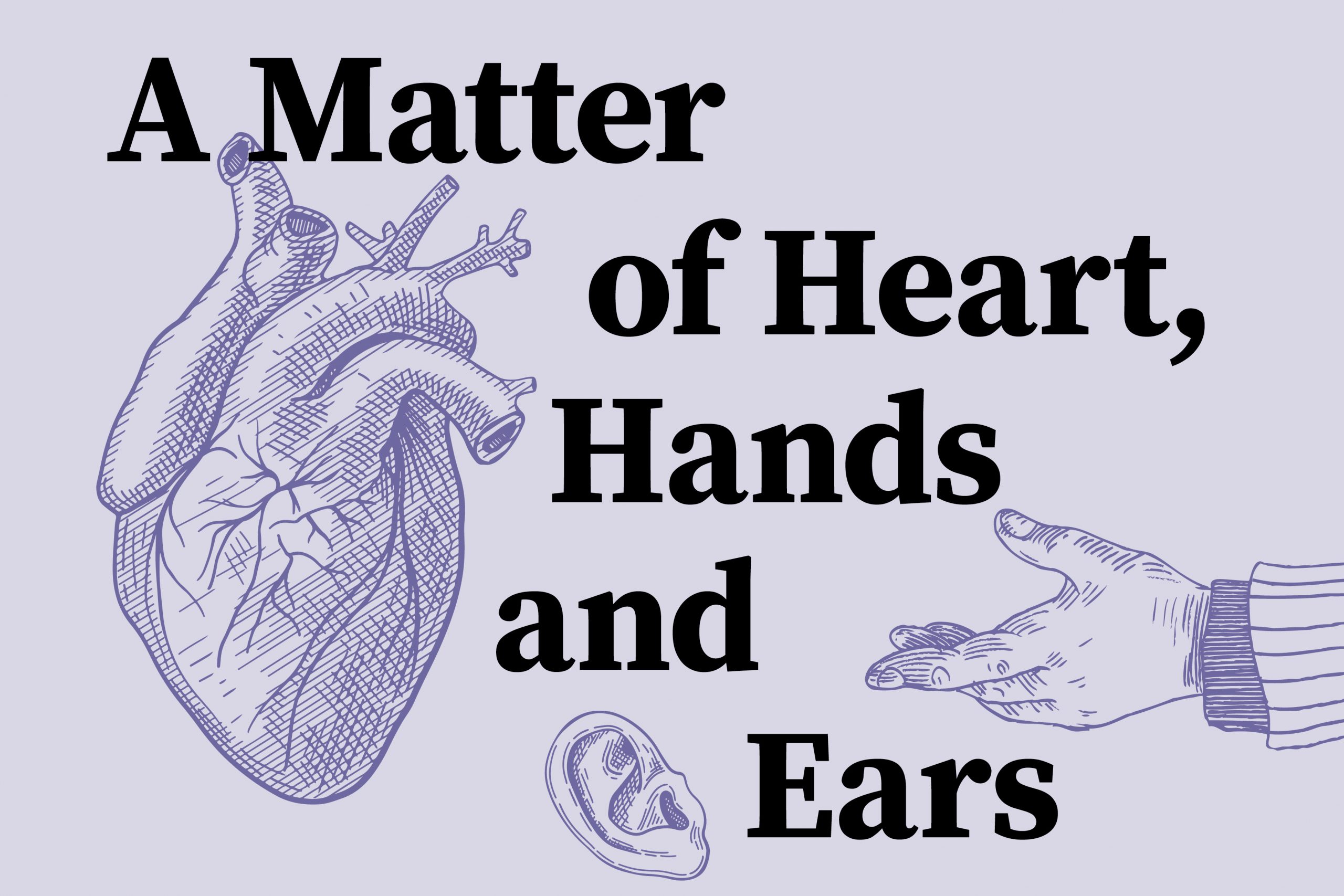

So as much as I rely on my hands to help patients, sometimes it’s the ears that make the difference, even in a discipline like glaucoma. Glaucoma is a feared disease, and yet, there is not enough awareness of it.

An elderly patient I saw recently almost cried in relief when I told her that she does not have glaucoma. The weight off her shoulders was almost palpable. To her, getting this potentially blinding disease was akin to getting a death sentence. And she is not the only one. Surveys have shown that people are more willing to lose a limb, or even lose their lives than go blind. This is how many people feel about getting glaucoma, but it does not have to be this way.

“It’s a long term journey—it’s important to treat the disease and the sufferers, and listen to their needs whilst providing suitable solutions along the way, that involve eyes, ears and hands.”

In our world of instant gratification, we often look for solutions which are fast, and one-off, but glaucoma is a disease that is not addressed with a single pill, or a solitary surgical solution. It is analogous to hypertension, which can be controlled, but you don’t really eradicate the problem. So it’s a long term journey—it’s important to treat the disease and the sufferers, and listen to their needs whilst providing suitable solutions along the way, that involve eyes, ears and hands. Here are the stories of a couple of my patients.

The Angry DJ

My first story is about a young man, who had diabetes and glaucoma. When I saw him, he was working as a DJ and bartender, working late into the night, with little concern for his health. He drank a lot, ate like there was no tomorrow, and smoked like a chimney. By the time he was 25, he had lost vision in one eye, and had multiple treatments for his condition elsewhere. He was angry with life, the various restrictions on his diet, the many clinic visits to various doctors, and the frustration of having to use many types of medications.

So I took a multifaceted approach to this young man. I put him in touch with our dietician, to help him manage his meals, then simplified his medications, both oral and eye drops, especially since he had poor vision at one point in both eyes.

Most importantly, I tried to listen, so I could find out what made him tick and potentially motivate him to get his treatment. As he enjoyed being a DJ, I convinced him that if he got treated, he would be able to see well enough to continue with what he loved doing.

Then after all that, we began to work on his eyes, with lasers, and more surgeries. These were painful and there were many long hours in the clinics, operating theatres and rehabilitation. But now I could see light in his eyes and occasionally a smile even.

I saw him recently. He has retained good vision in his left eye, no longer needs eye drops and has adopted a healthier lifestyle. He has also taken up a part time job with the Health Promotion Board as a social distancing ambassador during the downtime experienced by people employed in the entertainment and leisure industry. Despite the current challenges, he remains optimistic and takes the COVID-19 crisis in his stride.

Diabetes and glaucoma

Diabetes is the bane of the modern world, with significant numbers of people in Asia and elsewhere succumbing to this metabolic epidemic. Like glaucoma, you may not feel much is wrong in the early stages but when the complications occur, there are many serious consequences. In many serious cases, the eyes are affected and this can result in a form of glaucoma known as neovascular glaucoma, which can be difficult to treat.

Thankfully, modern medicine has meant this disease can be managed. But the treatment needs a partnership between the patient, his medical doctor and the eye surgeon. Similarly, congenital glaucoma is another long journey for both patient and caretakers.

The boy with an endless supply of smiles

This boy was born without an iris, a condition called aniridia. He had eye pressures that could not be controlled with eye drops. As with most cases of congenital glaucoma, surgery was required very early on in his life. Despite living with rather poor vision, he remained cheerful and playful.

I met his mum, and explained that it would be a lifelong journey together for both the child, the mother and the doctors looking after him. And there would be many operations, the need for medication. Long after I have retired from practice, this young boy will continue to require care.

Even though the mother had already seen a few doctors, and was probably aware of the gravity of her son’s condition, it still took a while for everything I told her to sink in. But both mother and child are blessed with one quality that will serve them well throughout their lives: a bright, positive disposition.

When I first saw the child, he greeted me with a megawatt smile, and had one of those faces which could get away with murder. He prefers females to examine him, so I knew he had some decent vision because he could definitely discern that I most certainly was not one!

Examining a child takes extra patience, and a lot of cajoling. You soon learn to contort your body into various positions to enable you to examine the writhing little body who believes that there is a contortionist residing in every eye surgeon. You have to set some time aside, and some days, despite your best efforts, a child can prove too fretful to examine. A good warm up with comprehensive stretching, some muscle rub after and a good cup of coffee are all part of the routine involved in examining him. Just think of that song “I like to move it, move it” and play it back at twice the regular speed.

About the

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a

blinding disease

often with no symptoms.

It is not addressed

with a single pill,

or a solitary surgical

solution. The treatment

needs a partnership

between the patient,

his medical doctor

and the eye surgeon.

Ultimately, with rising eye pressures, we had to perform surgery and typically we operated on one eye at a time, and allow it to recover before we go on with the other eye. It is important to involve all caregivers as they will be the ones who will administer the eye drops for the child, as well as to take care and keep the child from touching or rubbing his eye post-surgery. I always share with both patients and their parents that once you embark on this journey, it’s a long-term partnership to care for the child.

When the young boy first came, he was in pain, his vision was poor and the eye pressure was rising. It was important to listen to the worries that the mother had, then try to help her manage the care of the child, and finally plan for the surgeries the boy required.

Thus far, he has had three surgeries, including a cataract operation. Soon, we will schedule mother and child to talk to our occupational therapist in our low vision clinic to optimise what remaining vision he has. He is starting school, and continues to live a full life, which is vital for both his physical and mental health. He has a younger sister, who is thankfully normal and the mother has taught her children to look after one another so that the boy is assured of a buddy on his lifelong journey.

There are many challenges that lie ahead for the boy, but he is blessed with a sunny disposition and the support of a mother who will never give up on him. And that always makes my day even though I often get a sore back from trying to examine him in the clinic.

Glaucoma is a blinding disease, often with no symptoms. Even so, it can be treated. Through the quarter of a century of practice thus far, I have journeyed with many patients and learnt a lot about listening and more from them. Together, I believe there is light at the end of the tunnel, and that vision of hope will not be extinguished.

This is an edited version of a commentary that was first published in TODAY on 19 March 2021.