Issue 39 / August 2021

DOSSIER

Walking in Their Shoes

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as circuit breaker measures imposed throughout Singapore from April to June 2020, the healthcare and social needs of marginalised communities were brought even more to the fore. People were urged to stay at home and only leave their residences for “essential activities”. The chatter and buzz on the streets of Singapore faded into an eerie quiet. For some communities living on the fringe, adjusting to the “new normal” became a new reality they had to face and tackle.

t was in this context that we—Phase 1 NUS Medicine students—embarked on a five-day “Medicine for the Marginalised” experiential learning journey (MMEJ) from 14 to 18 December 2020. This experiential programme was crafted and helmed by Associate Professor Tan Lai Yong for students to learn about the social determinants of health among vulnerable groups such as the homeless, elderly and former convicts.

Twenty-six medical students settled in at the Kampung Siglap Life Skills Training and Retreat Centre on our first day of MMEJ. The centre engages with displaced individuals and families to promote their well-being, by providing them with skills necessary for independent living. At the centre, Mel, founder of community dance group—Plus Point, candidly shared her life experience as a former drug abuser, which resulted in her serving two terms in prison. She founded the dance group to provide teens with a sense of belonging, and to keep them away from a life of drugs and unhealthy habits.

A dance led by Mel & Plus Point dancers

Joined by two other dancers, Mel led the students on a socially distanced dance routine. It felt poignant to be part of the routine once I understood Mel’s perspective. For Mel, dancing is her way of coping with stress and to keep from straying back into her previous lifestyle. For me, Mel’s story illuminated the mental and emotional turmoil of an unstable family and social environment which led to unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as stealing, fighting and drug abuse—a story that resonated with many of her dancers at Plus Point. Stepping to the beat of hip-hop music playing through the boom box, Mel danced on as we followed her energetic moves.

While Mel’s dance routine highlighted the ways in which art intersects and transcends social troubles, the night walk around Jalan Kukoh gave us an opportunity to experience how social architecture can shape community bonding. As an old public housing estate, Jalan Kukoh houses many rental flats—usually heavily subsidised—for individuals and families with no other housing options.

26

medical students took part

in the five-day

“Medicine for the Marginalised”

experiential learning journey from

14 to 18 December 2020

We began the nights’ activities with a sharing session. Under whirling ceiling fans at Jalan Kukoh Food Centre, Mr Irza, a volunteer football coach, shares with us his experience coaching teenagers from lower income families at a street soccer court on the rooftop space above the Jalan Kukoh multi-storey carpark.

Much like Plus Point, football training is a way to engage teenagers from at-risk backgrounds—by nurturing a sense of belonging and encouraging meaningful time outdoors. We learnt that through Mr Irza’s guidance and motivation, the teenagers are empowered to explore their passions and develop self-discipline through the sport. After the session, Assoc Prof Tan guided us through the corridors and stairwells of Jalan Kukoh as well as the adjacent Chin Swee Estate, observing the sights and sounds of the neighbourhood, particularly the rooftop street soccer court at Jalan Kukoh. Towards evening, we interacted with the estate residents, had dinner at a food centre where residents commonly visit, and spoke to an artist who usually paints in Chinatown. Known for his paintings of famous Singapore landmarks, this artist sat outside OG Chinatown to paint the landscape there. We spoke about our shared interest, photography, and he shared more about himself. We left Chinatown for Read Bridge soon after, as I thought to myself that I would soon see him again, seated in another spot in downtown Singapore, focusing on his artpiece.

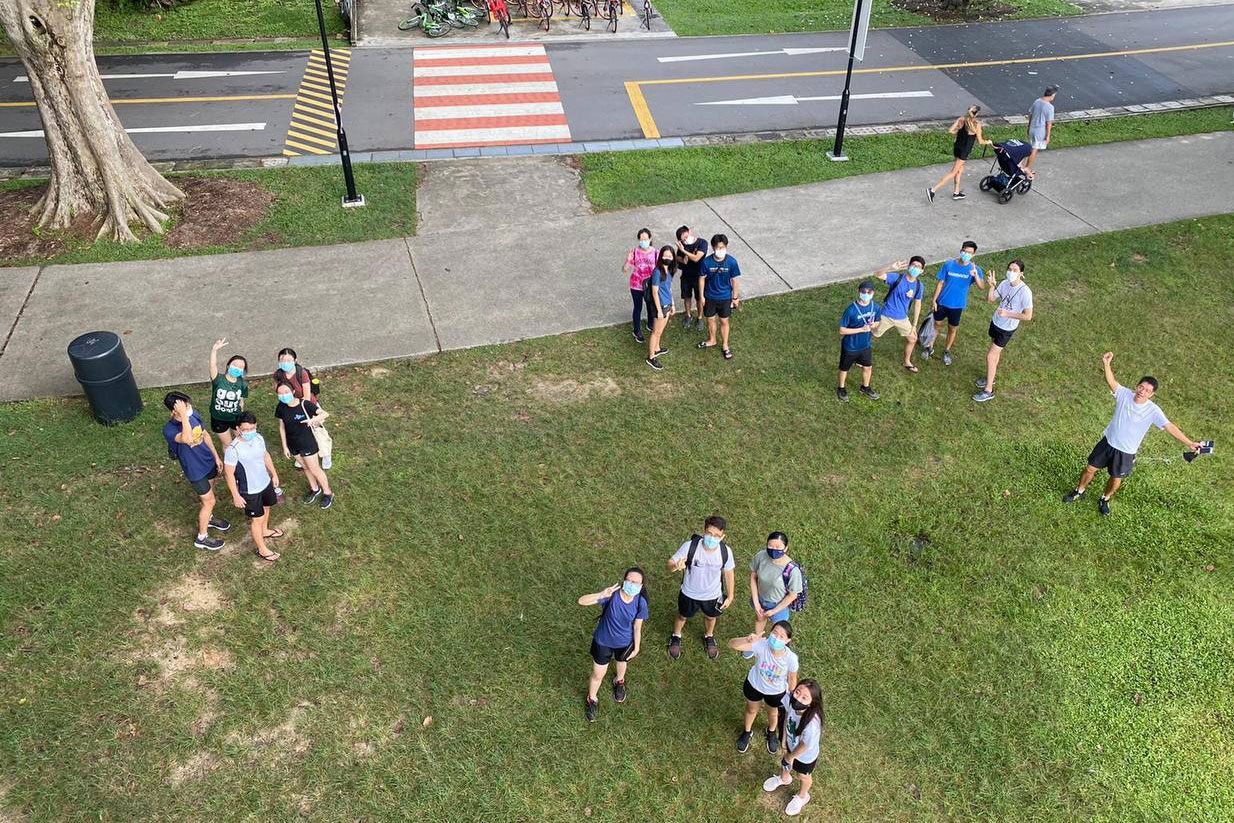

A morning walk at East Coast Park

The next day, we were treated to another morning of walking at East Coast Park. “Observe your surroundings carefully… what you see as well as what you do not see… the people who exercise and the people who eat at the food centre”, advised Assoc Prof Tan, before dismissing us, in groups of five, to explore the area. To the sounds of Chinese music played through speakers by elderly people practising qigong underneath ketapang trees, and the chatter of senior citizens heading home after a morning swim, we set off. My group struck up a conversation with a retiree seated on a stone bench at the edge of the parkland. Coincidentally, he shared with us how he used to serve as a general practitioner in the past when he lived in India, and how he now enjoyed mornings seated along the coastline as a retired doctor. We appreciated his advice for us as medical students and parted ways.

Another interaction which stood out to me was, getting to know a fisherman who had just returned with his fishing boat. Sharing how much the fishing scene has changed since the redevelopment of East Coast Park, the fisherman also recounted fond memories from the past as well as his love for being out at sea. Between our chat with the fisherman as well as the retired doctor, I discovered how green spaces can serve to deliver positive social, mental and physical health for all. As a respite away from dense urban centres, green areas provide restorative and serene spaces for reducing stress, carrying out lifestyle activities, and improving social interaction and community bonding.

Prata making session

We ended our walk at East Coast Park with lunch at Marine Parade Food Centre. Between food, exercise and lifestyle activities, health and medicine, we learnt to appreciate the intricacies that define individuals’ well-being—the social determinants of health that relate to what we medical students will experience clinically. Indeed, where food is concerned, we were given an opportunity to get our hands greasy in an interactive session making roti prata back at Kampung Siglap Centre. Choosing healthier oil to make the roti prata, we appreciated the chance to learn how diet and nutrition are important factors in health and healthcare. At a point where health takes centre stage in an individual’s well-being, to what extent can healthcare alleviate and mitigate these risks?

MMEJ ended with a case-study discussion conducted by Dr Paul Ang, and other lecturers from Family Medicine. Students were invited to role-play as family members of a drug abuser to discover how our social circle and immediate environment can determine our habits and coping mechanisms. This session summarised what we went through during the entire five-day programme—mindfully putting ourselves in the shoes of people from disadvantaged backgrounds, and coming to understand more intricately and sensitively, the ways in which our living environment and habits shape health.