Issue 38 / May 2021

Nursing

I Am a Nursing Student.

This Is How I Cared for My Dying Dad

As a third-year nursing student, I relished my peers’ stories on caring for patients on their deathbed in the hospital. Little did I know that the first death I’d witness would be my dad’s, in our very own living room.

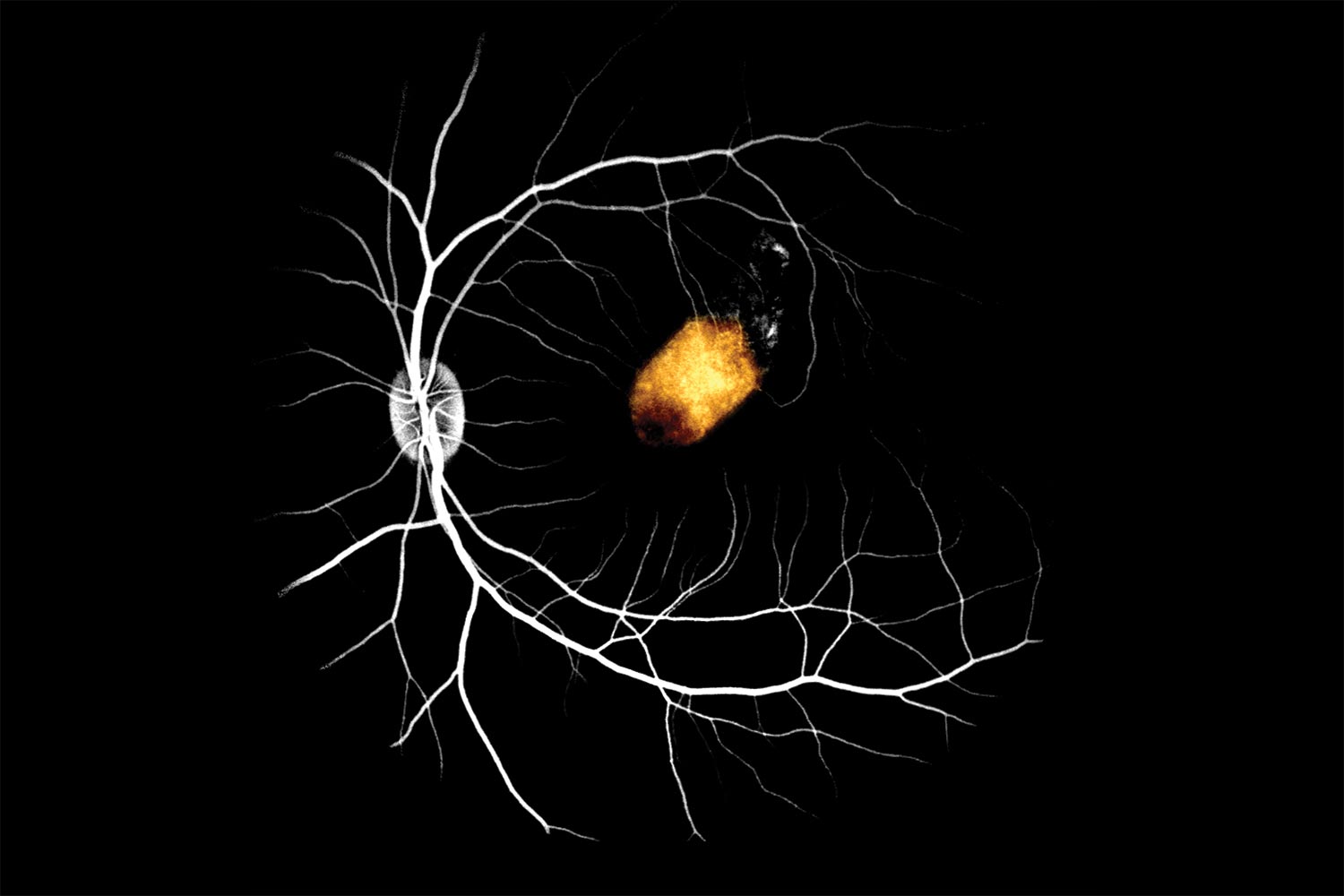

n January 2018, my dad was diagnosed with early stage nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC), which is cancer of the upper throat. He was 54 then.

I had just turned 19 and was awaiting my A-Level results.

My family was in disbelief, but the doctor gave us high hopes: “NPC is one of the most curable cancers. At this stage, 95% of people are cured, so don’t worry!”

By May 2018, things seemed to be going well with my dad’s condition. Scans showed that the tumours had almost been completely obliterated by the treatment.

My dad and I both returned to work—he as a civil engineering manager and me as a clinic assistant before I started university—and life continued as usual. We went for weekly chemotherapy sessions together, and were hopeful.

In August, several weeks before I started nursing studies at NUS, scans showed new small tumours in my dad’s other organs.

In other words, the cancer had spread, and getting rid of it was close to impossible.

His oncologist, ever so gentle, left us with these words: “Mr Say, the past few months we treated you with the intention of cure. Now, I’m afraid that will have to change.”

Nursing: A blessing in disguise

Over the next two years, my family—especially my dad—went through a lot.

I happily became a private nurse for my dad, complementing the emotional support that my mum and my siblings lovingly gave him.

I used the knowledge I gained in school to do physical assessments, observe his signs and symptoms, and explain each medication, procedures, and treatment plan to him.

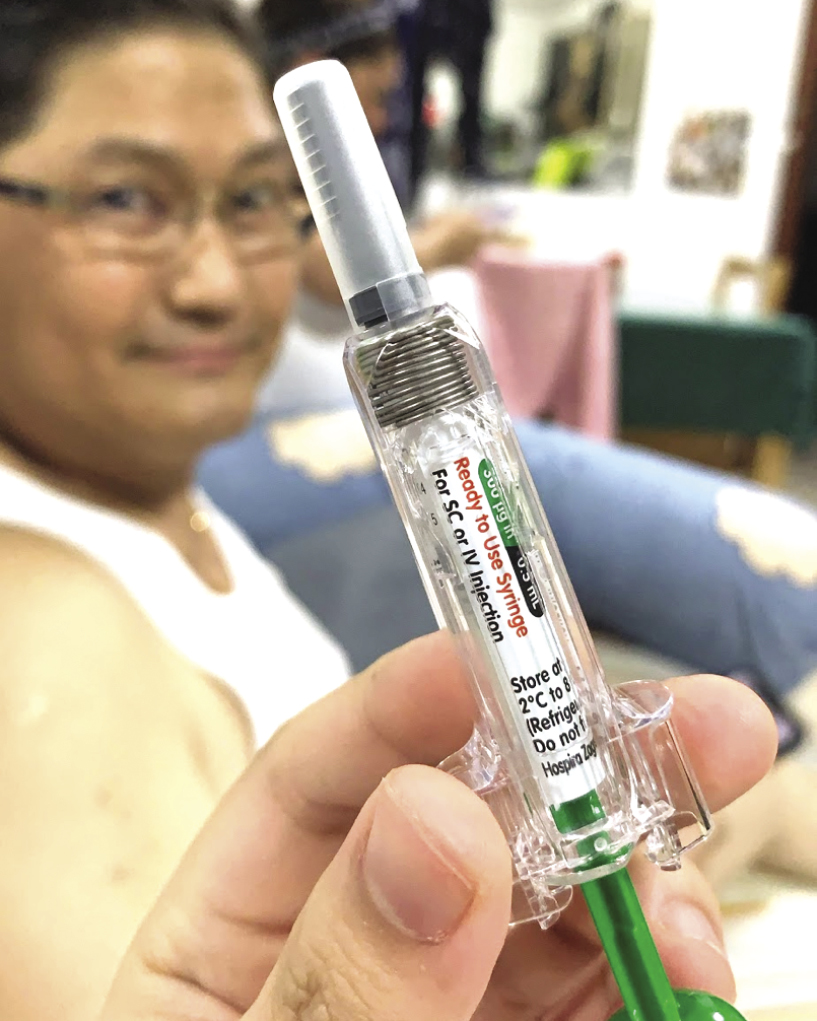

I especially enjoyed giving him injections and doing wound dressings for his surgery sites. He allowed me to learn from him, through his condition.

The author says that from her nursing classes and hospital placements, she learnt skills such as injection techniques and wound care, which her dad needed. (Photo courtesy of Paula Say)

Being a nursing undergraduate allowed me to provide the best possible care for my dad as a daughter and as a future healthcare professional. Everything worked together for good.

The death talk

Our family migrated to Singapore from the Philippines in 2008. I have a younger brother and older sister.

Filipinos love to sing. One night in August last year, upon my dad’s request, we sang karaoke at home.

The night ended with him serenading my mum with their favourite love song, Kahit Maputi na ang Buhok Ko, a number about growing old together, while still madly in love.

Little did we know that that would be the last time he’d be able to sing.

The next morning, he had a septic shock—a severe drop in blood pressure and an extremely fast, serious, and ruthless silent killer—and we had to rush him to the hospital.

With all my classes thankfully held online, I stayed in the hospital 24/7.

“Always be your patient’s advocate,” nursing school drilled. So I did.

I became my dad’s voice and gave suggestions to the medical team based on my nursing knowledge and observations.

Even though I was a student, the doctors listened and spoke to me as an equal, accepting some suggestions I raised. Those gestures validated my knowledge, competence, and increased my confidence as a future healthcare professional.

About halfway through that hospital stay, his oncologist took me aside.

For her parents’ 25th wedding anniversary in 2019, her father braved the side-effects of his treatment and booked a chalet for the family to spend some time together. (Photo courtesy of Paula Say)

“I think it’s time to talk to your dad about his final wishes,” she said. “Knowing you, your dad and your family, I thought it was best it came from you.”

In the hospital, I always knew exactly how to make my patients feel better. It was my forte.

But my dad and I had never had “the death talk” before. How do you break to someone he’s dying, and dying fast, let alone your own father?

I sat by my dad’s hospital bed. For the first time in two years, I wasn’t bursting with confidence.

For the first time in two years, I was fearful, holding back tears as I personally grappled with the fact that this could be it.

I used the knowledge I gained in school to do physical assessments, observe his signs and symptoms, and explain each medication, procedures, and treatment plan to him.

“We’re entering a new chapter of your care, daddy. I don’t think we have a very long time left.”

He wouldn’t even have the chance to see me graduate, I thought.

“I can feel it, Paula,” he croaked. “Explain the situation to your mum and your siblings. Take care of your mum, especially.”

And I did. That night, I left the hospital for the first time in two weeks, and talked to my siblings about how we could best support our parents, and each other.

The next day, I spoke to my mum with a heavy heart. It felt like walking on eggshells: Any wrong word could break her heart. She cried and cried, but she understood.

We understood.

Going home

Amidst the emotional turmoil, my dad made it clear that he wished to go home.

He was mostly bedbound at this point, and had difficulty moving due to the excessive water retention in his body.

To prepare for home, the hospital nurses and I taught my mum and my siblings how to change his diapers, do bed sponging, and carry out other basic nursing care and techniques.

I then spent the next week or so juggling between the demands of university and single-handedly setting up a home hospital in our living room from scratch.

The author set up a mini home hospital in her own living room, complete with an electric hospital bed, oxygen concentrator, intravenous stand, infusion pump and consumables, among others. Like in a real hospital, she also maintained updated nursing documentation charts for her dad at home. (Photo courtesy of Paula Say)

Again, nursing studies came in handy—how else would one know that a Christmas tree adaptor is needed for the oxygen concentrator?

My confidence quickly turned into nerves as the day neared. Bringing him home meant that I’d be the sole “medical personnel” around, and if anything happened, the responsibility would be on me alone.

But I was determined to fulfil my dad’s wish to be home with family.

Nursing studies came in handy—how else would one know that a Christmas tree adaptor is needed for the oxygen concentrator?

We finally brought him home, after five weeks in the hospital. He didn’t look good, and was drifting in and out of consciousness.

The doctors warned that he could pass on a few hours upon reaching home.

“Oh, I’m home already!” my dad exclaimed, mildly confused, realising that he was home only three hours after the fact.

It was also one of his last few intelligible phrases, as he continued to rapidly deteriorate over the next few days.

The doctors trusted me with his medical care at home—medications, injections, procedures and so on—emphasising on the most important things to look out for in end-of-life care.

My mum and my siblings helped with basic nursing care, while I focused on his medical care.

We all slept in the living room beside the hospital bed. My brother took the “night shift”, and would wake me up in the middle of the night to give emergency medications or adjust the oxygen machine.

His last breath

Three days after we brought him home, our worst fears materialised. He was unresponsive for several hours, and no amount of talking or shaking could rouse him.

I’d never seen a patient die during hospital postings before, and nursing school had not taught me the physical signs of the dying process.

Her father’s death left a hole in the author’s heart, but she gained a lot by journeying with him through his battle with cancer, she says. (Photo courtesy of Paula Say)

But some googling confirmed that my dad was ticking off the boxes by the hour.

Putting on my nurse persona, I went on auto-pilot, closely monitoring his vital signs.

Gently, I told my family that today might be the day, and to prepare our hearts and minds for the worst.

We then called up a few close friends and video-called relatives in the Philippines too. What followed was a few hours of people crying, thanking him, and saying goodbye.

By 3 pm, I asked to end all video calls, so that we could be with my dad as a family.

As what he would have wanted, we sang his favourite Christian worship songs—Healeth Thee, God You’re So Good and Goodness of God. For two-and-a-half years, despite his pain and suffering, he chose to worship and remind us of God’s goodness in our lives.

We sang in worship, prayed for peace and comfort, and cried our hearts out.

By 3.30 pm, I knew he was crashing—the pauses between his breaths got longer and longer. His hands were getting cold and clammy.

As a nurse, I am trained to spring into action whenever something looks wrong.

As a healthcare provider, I am trained to never give up—to save lives.

As a daughter, it pained me to know that the “right thing” to do was to watch my own father die, before my very eyes.

One by one, my machines failed to register his vital signs. His pulse became weak and scarcely palpable.

At 3.36 pm on 11 September 2020, my dad took his last breath, only five days after we brought him home. Calmly, and peacefully, he finally went Home.

Still on auto-pilot, using my stethoscope, I checked for heart, lung sounds, and other signs of life. Perhaps, that was my way of getting closure.

My family watched with bated breaths.

“Daddy’s gone,” I said, specifically to my mum. I knew she wanted to believe otherwise.

Paula Say at her father’s funeral in September 2020. (Photo courtesy of Paula Say)

Swinging my stethoscope over my neck, I stood at the foot of the bed “to give the family time to grieve”.

Standing there, amidst the wailing and crying, I realised that I was, in fact, part of the family—and should be grieving too.

Taking care of my dad at home, providing end-of-life care, gave us an avenue to tangibly exhibit our love and care for him.

Be it my sister’s massages, my mum and my brother changing his diapers, or me titrating his oxygen when he was breathless—I know that my dad appreciated those simple yet love-filled acts of service in his last few days.

Even at his deathbed, he allowed me to learn from him and through him, by being the first patient I ever saw pass on.

His death left a hole in my heart. But I gained a huge chunk in my two-and-a-half years’ journey with him on his battle against cancer.

Piece by piece, that huge chunk is what I’ll give each and every of my patients in the future.

Daddy, I love you. You’ve fought a good fight.

Though you wouldn’t get to see me graduate, or get married, or see some grandkids that you so dearly wanted, I know you’d be proud of me.

I’ll be your miracle.

See you at Home.