The ENABL Collaboration: Partnering With Pharma To Detect And Stop Major Cause of Liver Cancer

From left: Prof Ng Huck Hui (Co-Principal Investigator of this research programme and Assistant Chief Executive of A*STAR’s Biomedical Research Council), Prof Patrick Tan (Executive Director of GIS), Dr Karin Conde-Knape (Corporate Vice President at Novo Nordisk), Dr Ivan Formentini (Vice President at Novo Nordisk), and Assoc Prof Dan Yock Young (Co-Principal Investigator of this research and Head of the Department of Medicine at NUS Medicine). Photo taken at the EMULSION-Novo Nordisk Asian Biomarker Laboratory (ENABL). Copyright: A*STAR’s Genome Institute of Singapore

by Dr Khor Ing Wei

Dean’s Office

Non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the presence of fat in the liver that is unrelated to excessive alcohol consumption, is the most common chronic liver disease, affecting 30% to 40% of adults in the U.S.1 The prevalence of NAFLD is even higher in parts of Southeast Asia, reaching 40% in Singapore and Malaysia and over 50% in Indonesia.2

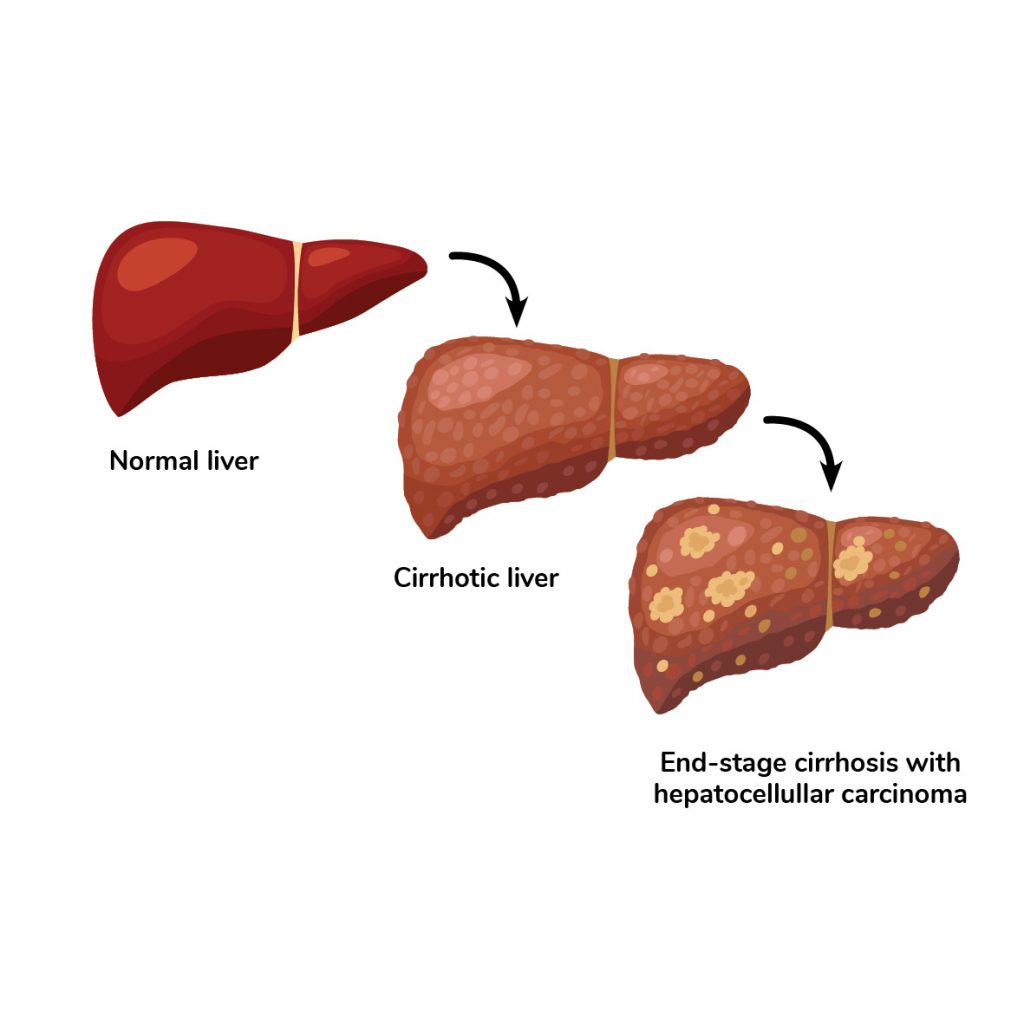

Although NAFLD is relatively benign in most cases, 20% of NAFLD patients have a more serious condition called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), in which fat in the liver is associated with inflammation and liver damage.3 NASH can progress to cirrhosis (scarring in the liver) and liver cancer, at which point few treatment options besides liver transplantation exist. Both NAFLD and NASH are growing in prevalence, and NASH is now the third most common cause of liver cancer and the second most common indication for a liver transplant in the U.S.4

NAFLD is strongly associated with metabolic syndrome, with each condition being the cause and the consequence of the other.5 The majority of NAFLD patients (80%) are overweight or obese, and 44% have type 2 diabetes.6 Asian NAFLD patients tend to be leaner and younger than Western patients.7 A study of 1061 NAFLD patients, published in abstract form, found that those with “lean NAFLD” had a lower survival than those with non-lean NAFLD, with lower insulin resistance and fibrosis but more liver inflammation in the lean subjects.8 These findings suggest that different mechanisms underlie NAFLD in Asians vs Westerners.

To learn more about how NAFLD develops in Asian patients, NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine) and the Genome Institute of Singapore at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) formed a strategic partnership, ENABL (EMULSION-Novo Nordisk Asian NAFLD Biomarker Laboratory), with Novo Nordisk, a Danish pharmaceutical company that develops medications for diabetes, obesity and NASH.

This partnership is an important development for the Ensemble of Multi-disciplinary Systems and Integrated Omics for NAFLD (EMULSION), a national effort to establish a world-class fatty liver program that is funded by A*STAR’s Industry Alignment Fund – Prepositioning Program. EMULSION is co-led by the NUS and GIS.

ENABL aims to find new solutions to help diagnose, assess prognosis and treat NAFLD. The first clue that someone may have NAFLD is usually elevated levels of alanine transaminase in the blood, in the absence of other causes such as excessive alcohol use or viral infection. After that, liver biopsy and examination of the extracted tissue sample under the microscope is the “gold standard” used to establish the diagnosis. However, because liver biopsy is invasive and painful, it is not feasible for screening large populations of people. This is one of the reasons why many cases of NAFLD and NASH go undiagnosed.9

Although some studies have used ultrasound, blood tests or imaging with MRI or CT, these methods are not as sensitive as biopsy for diagnosing NASH. Development of more sensitive, non-invasive methods to diagnose NAFLD and NASH, such as tests based on biomarkers, will facilitate screening in a broader population. However, such tests require good biochemical markers for NAFLD, which are sorely lacking. The ENABL collaboration aims to address this urgent need by combining the strengths of the various partners. This would help more people with NAFLD, especially those in earlier stages of the disease, to obtain a diagnosis and start interventions to prevent their conditions from progressing to more severe stages, which are associated with much higher morbidity and mortality.

By defining the optimal thresholds for non-invasive blood or imaging tests, we would be able to make a diagnosis of those who are at highest risk [of NAFLD],” said Professor Dan Yock Young, Head of the Department of Medicine at NUS Medicine and one of the principal investigators of the joint programme.

“This strategic partnership with Novo Nordisk will enable EMULSION to look into biomarkers that are applicable across different populations,” added Professor Ng Huck Hui, Senior Group Leader GIS and Co-lead Investigator for the EMULSION programme. “This will enable rapid adoption of any diagnostic kits developed for these markers.”

Modifying existing non-invasive tests for NAFLD is another approach that the team of researchers will explore.

“By defining the optimal thresholds for non-invasive blood or imaging tests, we would be able to make a diagnosis of those who are at highest risk [of NAFLD],” said Professor Dan Yock Young, Head of the Department of Medicine at NUS Medicine and one of the principal investigators of the joint programme.

Similar to all metabolic diseases, the main interventions used to prevent or slow down NAFLD are diet and lifestyle changes. Although these preventive measures can be very effective, many people find it difficult to maintain these for a lifetime. This leads to another aim of the academic-industry partnership.

“We hope to be able to develop more specific, targeted and efficacious treatment strategies to add to the universal general recommendations of dietary and lifestyle management,” explained Prof Dan.

REFERENCES

1 National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Definition & Facts of NAFLD & NASH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health- information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/definition-facts.

2 Li J, Zou B, Yeo YH, et a. Prevalence, incidence, and outcome of non- alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asia, 1999–2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:389-398.

3 Spengler EK, Loomba R. Recommendations for diagnosis, referral for liver biopsy, and treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2015;90:1233-1246.

4 Younossi ZM, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroent Hepatol. 2018;15:11-20.

5 Lonardo A, Nascimbeni F, Mantovani A, Targher G. Hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis and NASH: cause or consequence? J Hepatol. 2018;68:335-352.

6 Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease — meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

7 Cho HC. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Nonobese Korean Population. Gut Liver. 2016;10:117-125.

8 Dela Cruz AC, Bugianesi E, George J, et al. Characteristics and long- term prognosis of lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:S909. [Abstract]

9 Alexander M, Loomis AK, Fairburn-Beech J, et al. Real-world data reveal a diagnostic gap in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Medicine. 2018;16:148.