Dr. Henry Lee: Inside the Mind of a Forensic Scientist

Dr Henry Lee – one of the world’s foremost forensic scientists and the founder of the Henry C. Lee Institute of Forensic Science at the University of New Haven, Connecticut, USA

As part of the 10th run of the Chao Tzee Cheng Visiting Professorship Programme 2019, NUS Medicine welcomed one of the world’s foremost forensic scientists Dr Henry Lee, who gave a lecture on the opioid crisis in the United States. Find out more about his friendship with the late forensic pathologist Professor Chao Tzee Cheng, as he looks back at his career, his critics and gives his take on the latest developments and synergy in science and pathology.

“I know nothing”, pronounced the 82-year-old who has solved more than 8,000 cases around the world, co-authored more than 40 books, was conferred numerous medals and awards. Explaining himself, Dr Henry Lee added, “Because the world is too big, there’s too much to know—it is impossible to learn everything.”

Dr Lee really needs no introduction, famously known for his critical role in the investigation of the murder cases involving John F. Kennedy assassination and American footballer OJ Simpson, and who has dedicated his life to the field of forensic science in the pursuit of justice. Perhaps it is this sense of intellectual humility that motivates Dr Lee to constantly adapt himself and which keeps him going.

Fast friends: A forensic scientist and a forensic pathologist

Dr Henry Lee (left) with the late Prof Chao Tzee Cheng

Dr Henry Lee (left) with the late Prof Chao Tzee Cheng

(Photo credit: Dr Henry Lee)

Dr Henry Lee first met the late Prof Chao in 1983 when they were both invited to give a keynote address at a scientific conference. The instant friend- ship lasted many, many years until 2000 when Prof Chao passed on.

“Basically in Singapore, in the forensic field, everyone knows Professor Chao. He represents Singapore very well.” Dr Lee highlighted that with his knowledge, his warm demeanour and his openness, Prof Chao was able to quickly establish an international network which he could tap on when needed, to help with solving crimes back when technology was limited.

“He’s a teacher, he’s a friend, and most importantly, he changed our world.”

— Dr Henry Lee, on the late Prof Chao Tzee Cheng

Dr Lee added that Professor Chao was often interested in what the new generation of technology was and what new scientific techniques were used in the laboratory in the United States, “He’s always the first one to come over to learn, to observe.”

Despite the major differences in applications and techniques of forensic pathology and forensic science, Dr Lee reckons that both should work together at the end of it all. “This was something both of us agreed on: to protect the public, to find the scientific truth. That’s the spirit of Professor Chao—and I really learnt so much from him.”

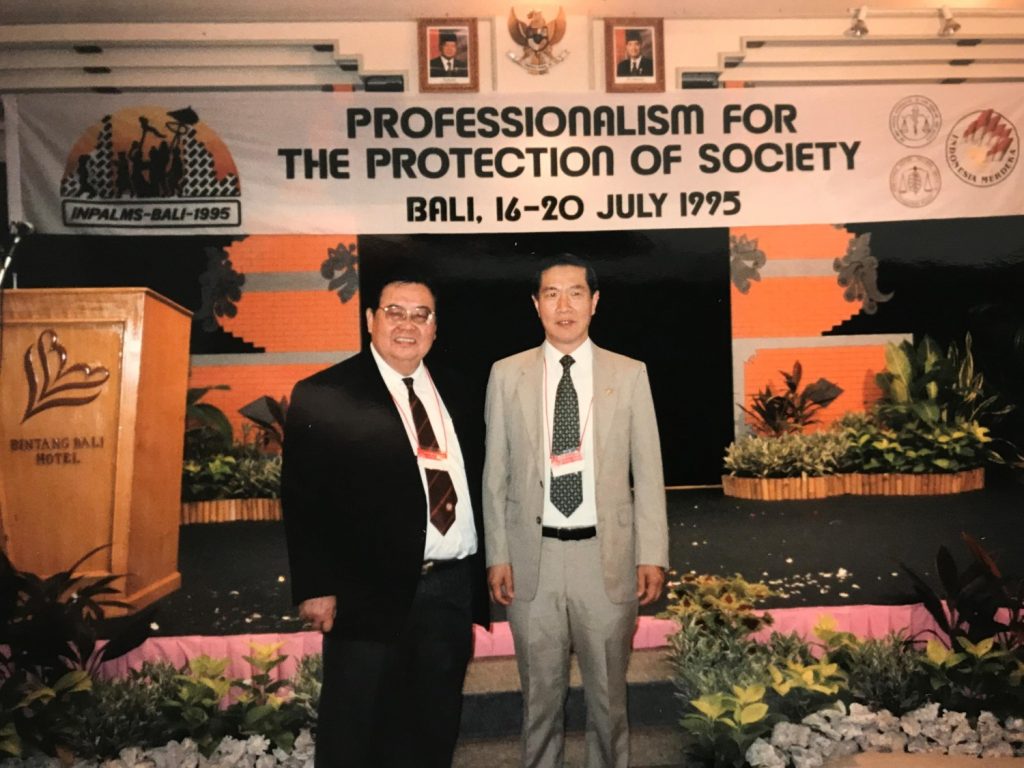

Dr Lee and Prof Chao at a conference in Bali in 1995

Dr Lee and Prof Chao at a conference in Bali in 1995

(Photo credit: Dr Henry Lee)

Rising above the negative

“As a forensic scientist, it is a “no-win” situation.”

Having played prominent roles in numerous high-profile and highly-controversial cases in his career—such as in the O.J. Simpson trial and the “woodchipper” murder in the United States, Dr Lee shared that forensic scientists definitely have a hard time, “One side is going to like you, while the other side is definitely going to hate you, depending on which side the expert testifies for.”

“Make good notes, document everything, and that will protect you because otherwise, others are going to say anything they want. But the truth will prevail.”

Dr Lee has been a prominent player in many of the most challenging cases of the last 50 years and has worked with law enforcement agencies to help solve more than 8,000 cases in his career as a forensic scientist.

Dr Lee has been a prominent player in many of the most challenging cases of the last 50 years and has worked with law enforcement agencies to help solve more than 8,000 cases in his career as a forensic scientist.

(Photo credit: Dr Henry Lee)

Dr Lee added that things only get complicated with “fake news”. He shared that the way TV news media report crimes have changed. “In the 1960s, they report case facts and let the viewer make the decision. By the late 70s and 80s, the reporter reports some of the facts that lead the viewer to a decision. By the 90s, reports only present a small portion of the fact, trying to make the decision for the viewer. But by the 2000s onwards, some reporters report no fact at all—some even make up the facts.” He is aware that there is a lot of fake information out there and now, “the viewer can’t even decide what is fact or not.”

“So what can you do? All this is human nature; and that’s part of what we deal with in our profession”, he said. The best one can do for him or herself as a forensic scientist is to keep all the records no matter what. Dr Lee emphasised, “Make good notes, document everything, and that will protect you because otherwise, others are going to say anything they want. But the truth will prevail.”

Embracing progress and change

Alongside technological advancements, the field of forensic science has evolved to almost 36 different sub-disciplines today. Some are crime scene-related, some are related to e-crimes, while others, such as forensic pathology, are medicine-related.

From early anthropological measurements which yielded inconsistent results, to blood typing and to the latest biometric measurements, Dr Lee noted that we have come a long way in our methods of human classification and identification—which have greatly helped advance scientific techniques employed in solving crimes. All this would not be possible without progress in forensic pathology, where the discipline itself has become so specialised in the area of human identification, where pathologists could get information from a multitude of both physical and physiological traits. “Forensic pathology progresses together with forensic science to deliver what is relevant and possible in the current century,” he said.

Speaking of the current century, Dr Lee acknowledged that as societies move towards digitalisation, the proliferation of digital enclaves would bring about new problems as it would be increasingly difficult to identify people in the digital and online space. His response to this: “It is a natural development.”

For Dr Lee, change is the only constant and he believes that the various disciplines will naturally adapt using the latest technological advancements. Simply put, “we have to accept the new science and technology”, he added. Just as how forensic scientists are moving into a new era of forensic science by incorporating artificial intelligence in their constant expansion of various databases, forensic pathologists no longer only perform autopsies, but also gather a slew of information stored in databases to help determine the cause of death or illness.

“It is an exciting world, but it can also bother us, especially the older generation,” he shared. When asked how can societies then adapt to such new changes, Dr Lee candidly shared, “I have no answer; I’ve tried to learn every new gadget but I’m just not quick enough… But at the same time, I’m so happy I don’t have to worry about it anymore, I’ve become a piece of history.”

Dr Lee shared that the use of artificial intelligence and big data is now “the future of solving cases”. However, Dr Lee also cautioned that for both pathology and forensic science, even with the help of artificial intelligence, we still need to have a human to make decisions. Artificial intelligence or any form of the latest technology is important in helping us solve cases but we cannot take away human judgement in the process.

Words for the next generation

For those who are interested in embarking on a journey in the forensic field, Dr Lee first warned that being a forensic scientist means long hours.

“People think that forensic scientists are what they see in the movies— they drive nice cars and by the second commercial, they’ve already figured out [the case] and can decide what to have for dinner. In reality, one often has to respond to emergencies and go without food or drink for the next ten hours after that!”

He has some advice to those eager to pursue a career in forensics or medicine, “Always be curious and willing to learn, willing to admit what you don’t know,” Dr Lee said. “Your best instrument to solve crimes is the telephone. I can easily call up somebody who knows something when I’m faced with a situation I’m unfamiliar with. It’s useful to have friends and networks that you can go to for help when you need it!” He urged young forensic scientists, “Build good scientific knowledge in your mind, be courageous and take up challenges, and have honesty in your heart— you have to be honest and frank in your life”.

Chao Tzee Cheng Professorship in Pathology and Forensic Science Programme 2019

In memory of the late Professor Chao Tzee Cheng, the renowned forensic pathologist who elevated Singapore’s level of professionalism in this field, his friends, students and colleagues set up the Chao Tzee Cheng Professorship in Pathology and Forensic Science in 2002. This includes a regular conference programme that is organised by the Department of Pathology at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

Its 10th run in 2019 brought together eminent professors in the fields of pathology, forensic science and law to share their expertise and enhance cooperation in research and education.

A panel discussion during the programme with (from left) Dr Henry Lee, Assoc Prof Tan Soo Yong (Head of the Department of Pathology, NUS Medicine) and Assoc Prof Stella Tan (NUS Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science)

A panel discussion during the programme with (from left) Dr Henry Lee, Assoc Prof Tan Soo Yong (Head of the Department of Pathology, NUS Medicine) and Assoc Prof Stella Tan (NUS Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science)

Read more of the event highlights here.