Are You The Cure?

Besides equipping students with sound clinical skills, a key focus of NUS Medicine is to nurture caring and compassionate healthcare professionals. The following stories are from our top prize winners of an essay competition, “Are You the Cure?”, where students and staff were encouraged to think about values in healthcare and let their creative juices flow into the form of short stories.

The Cure for Impudence

by Cheng Ryui-Wern, Reuven

Phase V Medical Student

Doe-eyed, nervous, hopeful, brand new laptop in hand

Spring in my step, up the lecture theatre stairs, this shall be my throne: the top left corner facing the stage

G-protein coupled receptors, Flexor Carpi Radialis Longus, Parietal Cells, Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation

The world in my palms, the possibilities endless, the lessons equally endless

“Let’s get a quick bite, pack lunch, the lecture’s gonna start soon”

“Don’t need lah, the doctors are always late!”

Clueless, hesitant, a space-occupying lesion, but still hopeful, school-issued iPad in hand

Clinicals is a foreign land, every PSA is a sister, every sister is a Sister

2pm clinic, 1:55pm, I give a knock, “Hi is this Dr X’s clinic? I’m scheduled to join him today.”

“Oh, come in boy, no worries, he’ll usually be late, you can get a chair from the pantry.”

The buzz of the afternoon clinic crowd fails to drown out my thoughts,

“then who sees these patients?”

—

The door swings open, lanyard and handphones on the table, I stand at attention

“Good afternoon Dr X, I am Reuven a thir-.”

“Okay sit down.”

—Silence—

2:45pm, “Okay, call the first patient in.”

2:49pm, “Okay, please wait outside.”

“Doctor I also have this hand pain.”

“Okay I’ll refer you to the hand doctors, please wait outside.”

—Silence—

2:51pm, “Okay, call for the next patient.”

Tired, overwhelmed, dare I say jaded, large kopi-o-kosong in hand

Enter the tutorial room to an unexpectedly large crowd,

“Eh, is your whole clinical group here? Heard this tutor will lock the doors if we come late.”

The door swings open, stern demeanor, coffee mug on the rostrum, pin-drop silence

7.30am, doors locked, I thought: this is the first time the whole class is on time!

The door handle rattles, flustered faces by the door frame: or so I thought.

—

“Good afternoon Dr Y, my name is Reuven, a final year medical student, may I join your clinic today please?”

A warm hand extended, a brisk hand shake, “Come in young man, I was just about to call our first patient.”

“Good afternoon Mr Z, so sorry for the long wait outside, how may I help you today?”

It was 15 minutes before Mr Z’s scheduled appointment.

—

6:15pm, “Thank you for joining my clinic young man, you’ve been a great help.”

No Dr Y, I should be thanking you, for being the example that I needed all this time.

Tired, overwhelmed, heart swelling with gratitude, change in my hands

The Cure for Impudence is Punctuality,

the prevention is being early,

the treatment is a dose of earnest penitence,

that starts with me.

Looking past medical knowledge, I have fortunately met doctors who have taught me to treat others better than I would like to be treated myself. They have taught me to be a man for others, before self. And for that I swear to emulate, and be better, and to pass on this simple Cure for Impudence.

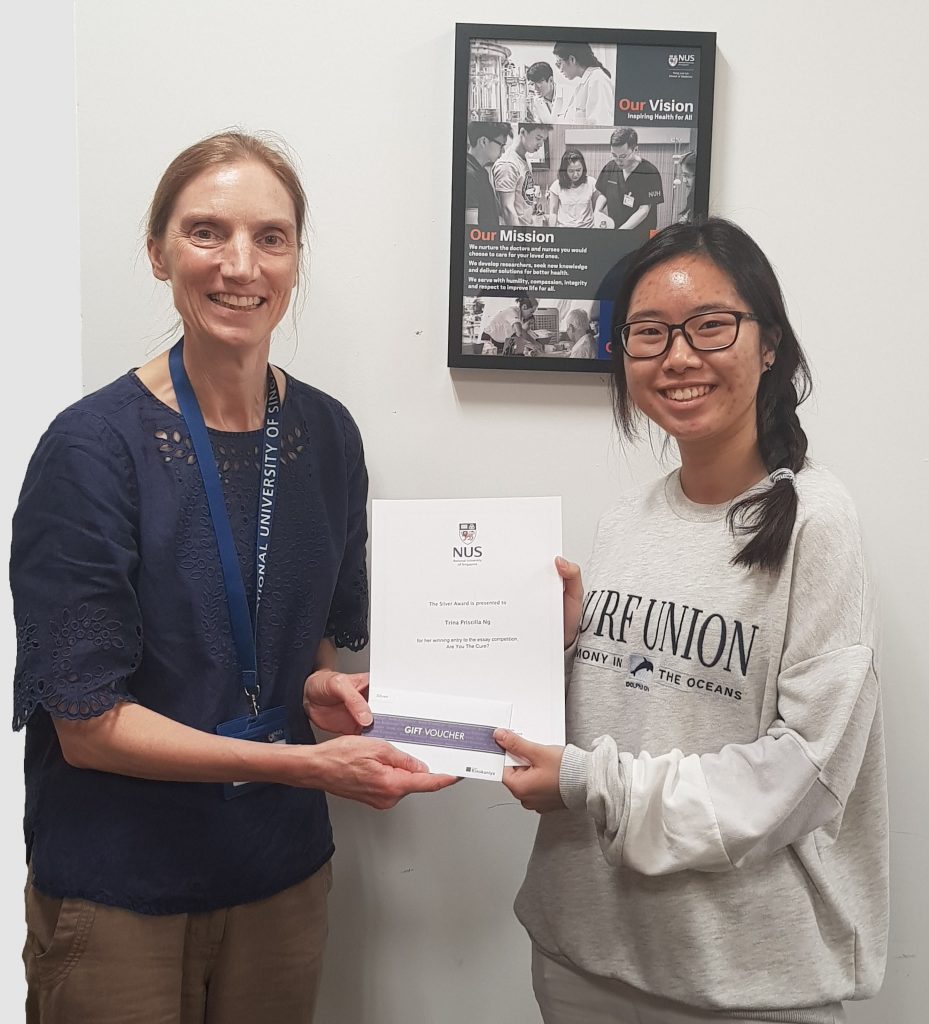

The Cure for Indifference

by Trina Ng

Phase I Medical Student

It is 8 in the morning on a Saturday. I am at a dialysis centre.

Auntie looks grumpy. As a result, I start to feel a little grumpy too. It is 8 in the morning on a Saturday.

Dragging a plastic chair behind me I took a seat and got ready to start the conversation. I was apprehensive—with a mask covering half her face it was hard to gauge her emotions. A few cursory introductions later she offers me a piece of her chocolate. She has proffered acquaintanceship.

Like me, she is apprehensive at first, but she opens up slowly. It starts in drips—she shares about her family. She complains about her sons bringing her too much food for breakfast everyday. I smile because I sense an undercurrent of warmth and pride; this sounds so familiar. A sense of being loved in excess is a sweetness that lingers.

I talk about my own grandfather and his love for cooking. Auntie springs, almost jolts to life as she begins talking about her Peranakan heritage, of her kuehs stained with blue butterfly pea flowers, her buah keluak curries too spicy for the non-native tongue. There is a pride and joy found in creating things that are your own. For a moment I find myself in the misty room of her memories. Somewhere, there is a tiny kitchen. Her grandmother is hunched over a bubbling pot. Somewhere else, someone is using a mortar and pestle, the pounding rapid, rhythmic and persistent.

Tucked away on the top shelf of a cabinet somewhere in the corner of this room are fragments of a distant past: a kebaya and one side of a pair of yellow beaded slippers. It is quite a beautiful world in sepia.

“It’s easy! I can make everything myself. I mean, I could make everything myself. Not now, I don’t cook anymore.”

The record screeches to a painful stop. She shares her feelings of helplessness. She tells me about how she feels useless now that she can no longer pursue her hobbies. Sometimes, with only the moon for company, she cries. And she prays. I am not religious, but I want to pray for her happiness too.

As I get ready to leave, I realised I had hardly said a word about myself.

Growing up, I was always taught that there was a power in being loud. To command attention, we learn to enter a room with head held high, to speak loudly and firmly so people will listen. Over time, I have learnt to do the same, spoke only at people, relished the sound of my monologue.

An hour of conversation unfurls years of me wanting to be heard. Perhaps, the cure to indifference is simpler than we think: listening without trying to plan out what next to say is kindness. Where understanding begins, indifference ends.

It is 8 in the morning on a Saturday. For once, I don’t regret waking up early.

The Cure for Duplicity

by Huang Chi Ming

Year II Nursing Student

Another shift from the attachment finally done and dusted. I only regretted that I did not finish earlier. On the outside, I said I missed the patients dearly, every one of them. However, I was excited on the inside to leave; to go out to enjoy the allowance I had earned, the fruits of my labour.

There were also times when we students interviewed the patients with so much care— enquiring about medical and social history, only to ignore that very same patient the next time we see them. I, regrettably, forgot my Standard Patient’s (SP) name after the module on effective communication. It was only when he waved at me—and upon seeing my puzzled expression, reminded me that he was my SP— that I remembered. I merely treated him only as a stepping-stone to getting decent grades for that module. I may be reluctant to admit, but, I was being duplicitous.

How then, I asked myself, will I establish a firm and stable therapeutic relationship with my patients without being fake? After nearly a year, I came to the conclusion that I am always putting on an act, apprehensive to show my inner self, for fear that I would be accused of not truly caring for my patients.

I came up with and tried a few solutions for myself. I stood in front of the mirror and told myself that I am enough. It is perfectly normal to want to get the best grades, a good reputation, decent pay cheques that allow me to enjoy life. However, caring for patients and executing care plans merely to obtain these would be unfair to the patients, myself and also the noble career of nursing. Sometimes just being myself and reminding myself of my initial passion to care for the sick allows me to take a step back for objective self-evaluation.

This is how I arrived at my next non-pharmacological cure for duplicity: I will earnestly recognise, admit and refine my shortcomings to avoid making the same mistakes again. The cure for duplicity comes from within. It starts from believing in ourselves, that we do not have anything to be ashamed of, and coming to terms with our own internal motivations. Nursing is a vocation that demands hard work, dedication, and compassion but not always at the same time. Gradually, as we progress, we earnestly own up to our failings. It is courageous to admit and forgive our own mistakes because to err is human, and to keep on caring is our humane mission.

The Cure for Hubris

by Dr Tam Wai Jia

Alumna

When we heard the hysterical shrieks, we knew someone had died next door.

Just days ago, a man in perilous condition was checked into the clinic near our home.

That weekend, scores of people came by.

In a foreign land, the cross-cultural stresses made simple day-to-day living challenging. In particular, new visitors at the clinic who stared at us at length each morning at our front porch frustrated me greatly.

As the hair-raising shrieks erupted into a cacophony of unrestrained screaming, we left home. When we returned, a crowd had gathered around our front porch. People were sitting on our chairs at our front door.

“Those are our chairs,” I said, to my own shock, a little regretfully.

“Do you share chairs in your country?” The matriarch of the family shot us a bloody look. “This is Uganda. And in Uganda, we share chairs.”

I wanted to retort, wanted to tell her that I was a doctor and that I had left behind a great career to be serving as a volunteer doctor in Uganda, that she ought not to talk to me like that.

But, panting heavily, I shut the door behind me, before I said something I would regret.

Suddenly, I was humbled. How quick we are to consider ourselves more superior. In Uganda, I often caught myself thinking, “After all I have given up, how can they treat me like this?”

That incident, however, enlightened me.

Serving others, was simply all about that – others. It was not about me, not about the house or career I had left behind.

While I was upset that our things were frequently being used and our privacy was often invaded, was I truly entitled to what I think I was?

Did I deserve staying at a home atop a hill overlooking the glorious sunset? Did I earn those chairs that were given to us? Did I deserve the no-pay leave graciously granted to me by my employers so I could serve in Africa?

When I started to see from a different perspective, I realized that I had no ownership rights not just over those chairs at our front porch, but over my entire life.

We often think we have much to impart to the locals. Instead, I am learning, we have much to learn from them. What comes across to us as their one-sided self-entitlement, is their value of sharing and caring for others in a heavily relational culture; what comes across as ingratitude to us, is merely their concept of family- they would do the same for us without expecting thanks; what comes across to us as being invasive, is just their way of showing affection.

On the contrary, what we perceive as independence in our self-made culture, is perceived as being self-seeking in theirs.

Later, we discovered that the person who died was not the elderly man, but a young child.

I am learning, that our values of right and wrong which are so easily circumscribed in our own culture, may be unceremoniously overturned in another.

Self-entitlement loses its compass when we realize it has nothing to anchor itself in.

As doctors, we are called to serve.

I am learning, that I too, need to learn how to share chairs.