Issue 48

Nov 2023

THE LAST MILE

By DR NOREEN CHAN, HEAD AND SENIOR CONSULTANT, DIVISION OF PALLIATIVE MEDICINE, NATIONAL UNIVERSITY CANCER INSTITUTE, SINGAPORE

At first glance he seemed like just another elderly man in hospital pyjamas, rendered thin and frail by age and illness (in his case, Parkinson’s Disease), now dealing with another bout of pneumonia. But what caught my eye was a large framed black and white photograph on his bedside table, showing a bodybuilder striking a victory pose next to an enormous trophy. I looked at the muscular young man in the photo—which was clearly from the 1960's—and at the patient, and had to ask “Is this you?”.

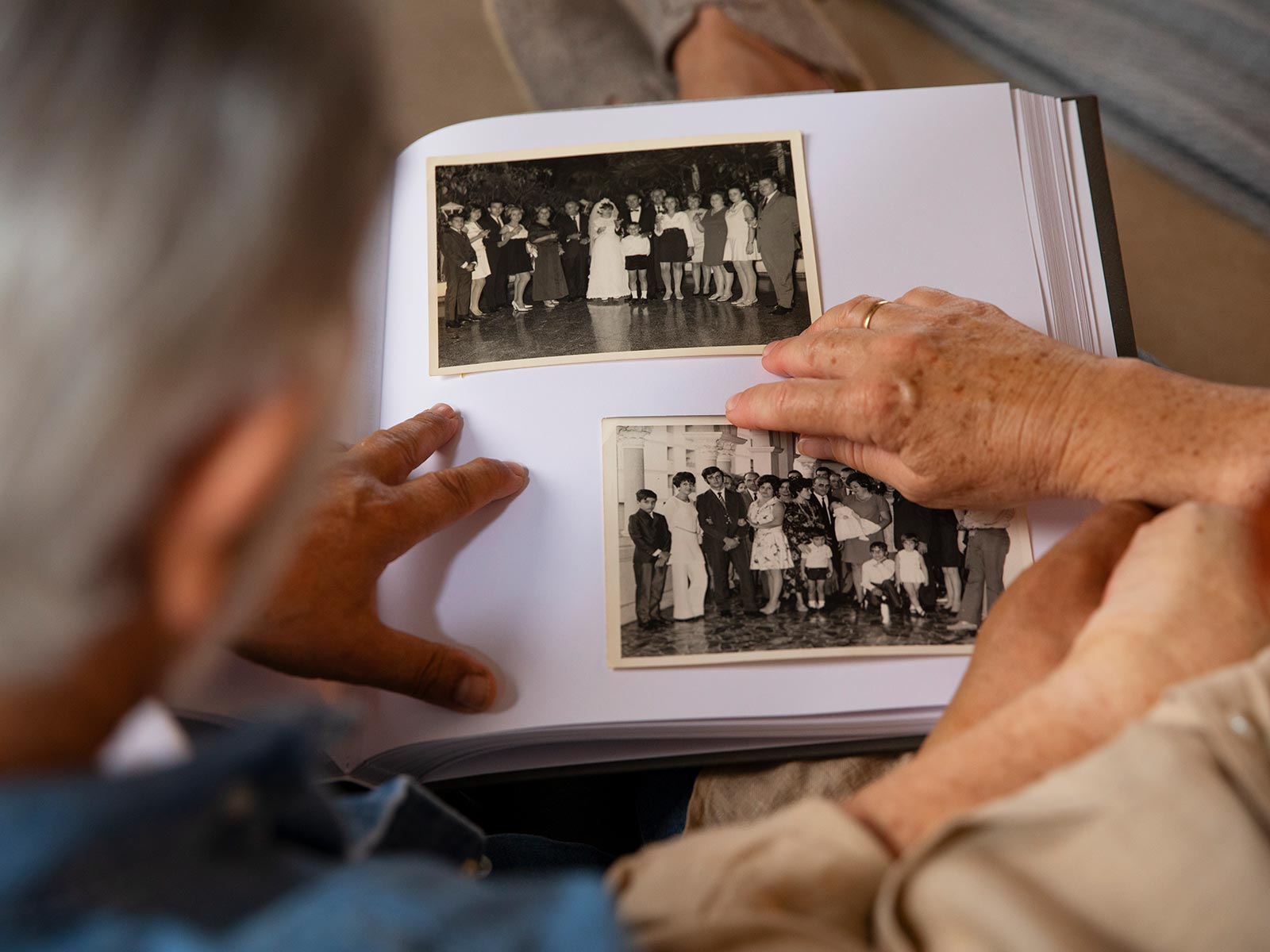

His daughter at the bedside immediately replied “yes, he was Mister Singapore you know!” and told me about how her father had to pursue his bodybuilding hobby as an amateur, how he was chased by girls but only had eyes for the woman who would eventually become her mother. This story was so embedded in the shared family history, that even the grandchildren knew it. Soon everyone was chatting excitedly and nostalgically, and the patient was so delighted that he allowed me to take a photograph of him beaming next to the photo.

Soon after that, I saw another man, this time suffering from cancer. He too shared memories of himself before his illness, when he was an all-round athlete who ran, played rugby and swam. Now bald, more than 10kg lighter and just about able to walk across the room, those memories were not comforting in the least, but bitter reminders of what he had lost, and would never get back. He did not want his old friends to visit him at the hospital, because “I do not want them to see me like this”. It was interesting how recollections of the past could have such different effects on different people.

Lest we forget

Memory is the process of taking information from the world around us, processing (or encoding) it, storing and later retrieving or recalling it (even years later). Memory scientists describe different kinds of memory, for example implicit versus explicit memory. The latter involves conscious recall e.g. of a phone number or address, whereas implicit memory is unconscious recall, like riding a bicycle after not doing so for a long time.

We are storing memories all the time, often without realising it. While effort, practise and repetition can help us to remember what we need, sometimes it comes down to the immediate and personal impact of an experience that cements a memory. For example, I can still remember where I was when I learned about the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center towers in New York on 11 September 2001; I was with my sister and her friend, in a small restaurant somewhere in the outer districts of Bangkok. I cannot remember what we ate (I suspect no one was very hungry), but I do remember the grainy footage of the first plane flying into the first tower, on a small boxy television at the back of the shop, as our friend translated the Thai commentary. And I remember the feeling of disbelief and the chilling realisation that this was not some special effects; it was real.

Remembering has many benefits, not least because it allows us to learn, reason and develop higher thinking skills. It also contributes to our sense of personhood and self-identity. Reminiscence Therapy is used in conditions of severe memory loss—whether from dementia or brain injury—to try to stimulate and preserve long-term memory. For older dementia sufferers, this is done through old photographs, music or keepsakes, or even creating a setting like a typical living room from 50 years ago. As portrayed in Royston Tan’s poignant short film “Ah Kong”, sometimes this “version” of the person is what is left, when everything more recent has been lost.

Pain and tenderness

But memories are not always benign as sufferers of PTSD or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder can attest. This is because memories are not just facts or the passive act of watching events play out on a screen; memories are deeply intertwined with emotions. The reason for this is that the part of the brain that processes emotions, the amygdala, is also involved in memory processing. The amygdala is part of the limbic system, which in turn is anatomically close to the region of the brain that handles olfaction or smells. Which explains why certain smells can evoke emotions and memories, like how the scent of Imperial Leather soap always reminds me of my father.

Human beings can be unreliable in their memories, and it is unpredictable what some people remember. Individuals involved in the same experience can recall it quite differently from their own perspective. People are also able to suppress memories as a form of self-protection, especially after a traumatic experience. But sometimes, these long buried recollections can resurface.

Some years ago, we were holding an examination at our hospital, and one of the stations involved the candidate assessing a patient. Suddenly an administrative staff member who was keeping time broke down. She had to leave the room and could not continue with the examination. During the debrief, it transpired that the scenario reminded her of her brother who had died from leukaemia. The session had triggered all her memories and pent-up emotions. Up until that point, she had felt fine, and from the outside, there was no hint that she had suffered such a devastating loss.

Memories are made of these

In Palliative Care, we do spend time with patients and families recalling memories, which could involve them sharing their illness journey (either as a patient or caregiver), or through a more guided process such as a Life Review. This aims to help people make meaning of their experiences. We also look for opportunities to make memories, through activities like granting wishes and legacy work. It could be something as simple as a family photo, or something more complicated like a solo exhibition of photographs or paintings. And it is as much for loved ones, as it is for the patient.

Patients and families living through terminal illness will face pain and struggle, but also fulfilment and joy and it is important that all those experiences are embraced. We live from moment to moment and those moments become memories, not only for patients, but also for those who will be left behind. Memories, like physical mementos, can be shared, treasured and passed down. How and where they find their place in our hearts and minds, how their personal meaning changes over time, is our choice.

Click here to watch the short film “Ah Kong”.

More from this issue

The Banyan Tree

The Science (and Art) of Doing in Health

The Banyan Tree

Take 5: Q&A with Professor Nick Sevdalis

Science of Life

Parasites of Viruses Drive Superbug Evolution