Issue 47

Aug 2023

THE LAST MILE

by Dr Noreen Chan, Head and Senior Consultant, Division of Palliative Medicine, National University Cancer Institute, Singapore

Teaching has always been part of a doctor's role. Seniors teach juniors, doctors teach students, peers teach one another, whether consciously or unconsciously. People learn not only from books or tutorials, but from what they observe is said and done, or not said and done. Hence the importance of the "hidden curriculum" which refers to what is learned outside of formal teaching, and which imparts norms and values of the profession and the workplace.

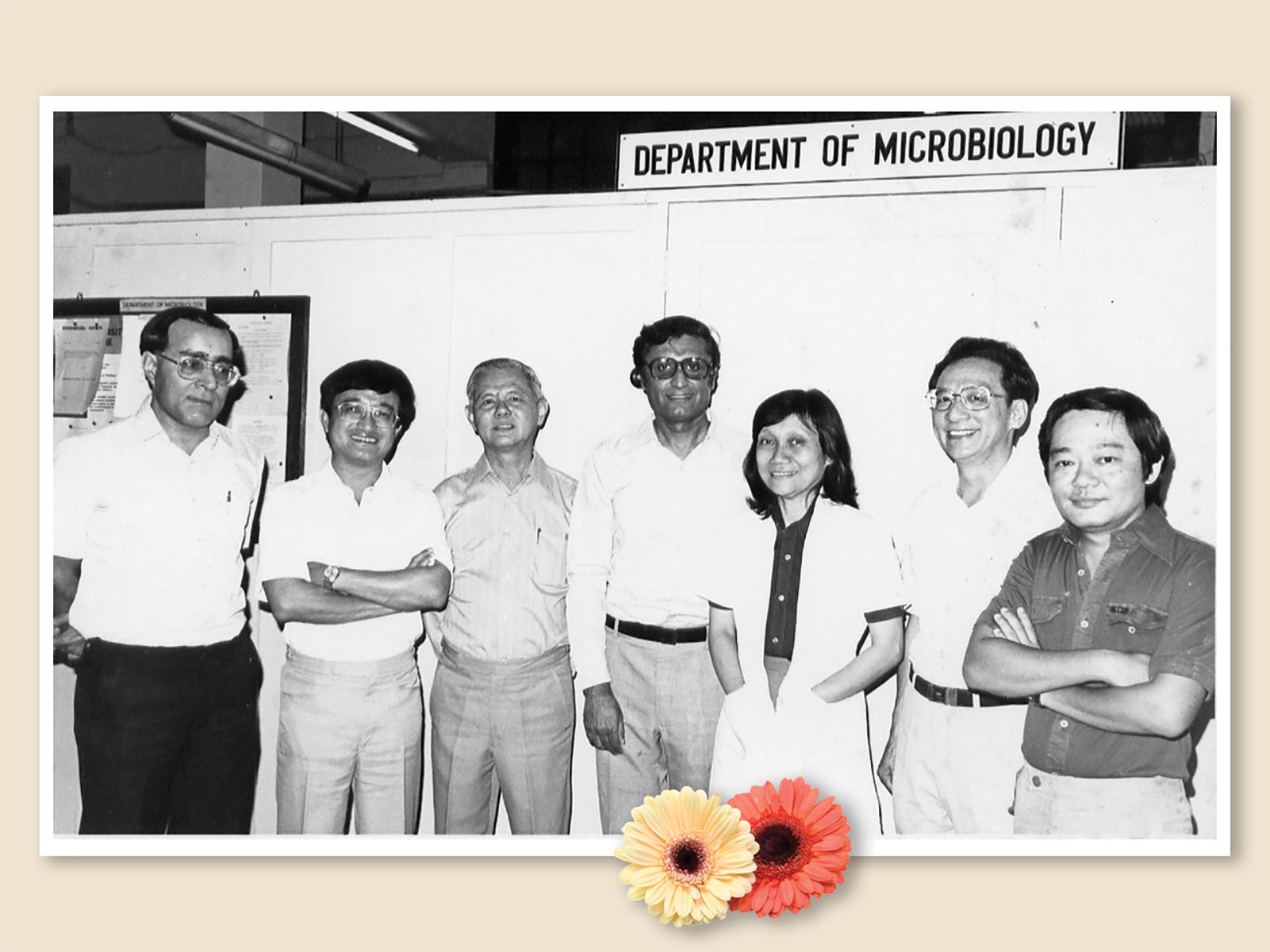

I have been privileged to have been involved in teaching for some decades. It started with my being asked to give a talk at a short course for doctors—I recall it was on gastrointestinal symptoms. I was then subsequently invited to organise the course, and over the years, expanded that to different topics and different groups of learners. It was through teaching that I was able to travel and network with palliative care colleagues in other countries.

What many do not realise about teaching is how it benefits the teacher. If you want to understand any topic better, teach it; because you will then have to be familiar with the main points, and through your students’ eyes, you will gain a fresh perspective.

This is especially true when you teach overseas. Palliative care by its nature is person- and family-centred, so context is everything. The foundational principles may be the same, but when applied to individual circumstances, the resulting actions may be very different. Teaching in unfamiliar settings therefore becomes as much of a lesson for the teacher, as it is for the learners. To quote from the song “Getting to Know You” (from the musical The King and I):

It’s a very ancient saying,

But a true and honest thought,

That if you become a teacher,

By your pupils you’ll be taught.

Let me share with you what I discovered along the way.

Flexibility is key

Between 2004 to 2006, I had participated in a capacity building project sponsored by the Singapore International Foundation, and went twice a year to work with the staff of a palliative care unit (PCU) in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

In retrospect our team of doctors and nurses was a little naive when we made our teaching plan. We had been told that the standard of English was variable, but when we arrived, we discovered that we really needed translators for everything. Hence the lectures had to be shorter, or the allocated time lengthened, to allow for the translator to convey the information in Vietnamese, line by line.

We also realised that due to differences in English proficiency and learning needs, we had to teach the doctors and nurses separately. At least initially, until the basic knowledge had been imparted, before we began to model behaviour to show how we could work together for the same patient. Our team members hailed from Singapore, Taiwan and Australia, so we could show that different backgrounds were not a barrier to teamwork.

One of the core topics in palliative care is “Care in the Last Hours/Days of Life” or how to care for the dying patient. In Vietnam, however, we discovered that very few patients actually died in the PCU. This was because it was the custom for families to rush patients home to die, even if this meant a journey of over 100km. Therefore, the teaching emphasis had to be changed to how to recognise that the patient is dying, and how to prepare the family to care, especially when there were no hospice home care services to provide support at home.

Translation is not just words, but ideas, feelings and beliefs

In Vietnam, certain concepts and terms seemed easy to translate, for example “pain score” (used to rate the intensity of pain from zero to 10). But other concepts like depression were problematic, as the formal term held very bad connotations that were akin to lunacy for the Vietnamese. They felt they could not ask patients if they were depressed as it could be insulting; thus we compromised and found a word that meant something like “do you worry a lot?”.

The social worker is a core member of the multidisciplinary team, but 25 years ago, there weren’t any in Vietnam that we knew of. And even asking caused a few sniggers, because the Vietnamese word for social worker that the PCU staff knew of, was a euphemism for prostitute. I am sure there is a proper translated term, but back then, it caused so much confusion that we just dropped the subject altogether.

Recognise what you do not have but do not always dwell on that; value what you do have and make the most of it

At that time, pain medications like the Fentanyl patch and Gabapentin were quite new on the market, but prohibitively expensive. Morphine, when it was available, was extremely cheap, as was the old antidepressant Amitriptyline which could be used to treat nerve pain. So we went through the hospital formulary and walked around the private pharmacies located near the hospital, to find affordable medications that could be used to manage common symptoms. And of course, there were good options; not a huge range, but good enough.

The hospital we were based at had almost 1,000 beds and 1,300 patients, so two patients sharing one bed was quite common. Patients who did not have relatives to accompany them—and therefore no one to help serve their medications and provide food—would be helped by neighbouring patients’ families. Everyone bore the crowded conditions with good grace, and took care of one another with kindness and generosity. The teaching team was humbled by the resilience we saw, and it made us appreciate what we take for granted at home.

Culture is learned and therefore mutable; practice can change over time

I have written before on the common practice of non- or partial disclosure of bad news, and not surprisingly, this would come up frequently during teaching in various countries. In Vietnam, we discovered that the staff did want to learn how to convey bad news, and once we had demonstrated a few times (through interpreters) that it was possible to share openly with patients and families, they took on the task themselves with enthusiasm.

A year after our project was completed, I returned for a follow-up visit and was gratified to observe that these communication skills had been maintained. One of the doctors was speaking to a patient newly admitted to the PCU for pain management. While exploring her understanding of her condition, the patient replied that she had stomach cancer. The doctor who had diagnosed her did not actually tell her about her cancer, but the patient was a nurse and was able to understand the medical reports. The conversation that followed between her and the PCU doctor was a lesson in honesty, gentleness and compassion that warmed my heart. We could not have taught those attitudes; the PCU doctor already had it in him, and it was a matter of giving him the tools and confidence.

It is said that a teacher “should not be a sage on the stage, but a guide by the side”. There are certainly times when one has to stand on a stage and speak to a large crowd, but clinical teaching is best done in small groups in the environment where care is being delivered. We do teach knowledge and skills, but perhaps we are most useful when we show our students their potential to be the best versions of themselves.

More from this issue