The Long Dawn

From colony to independence

1819 – 1965

The birth of modern Singapore as we know it now is inextricably linked to the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles on 28 January, 1819.

It was not an easy beginning. Singapore then was little more than a fishing village, mostly covered by jungle and a few buildings, a few acres of land under cultivation. It had a population of about 1,000 – about 500 Orang Kallang, 200 Orang Seletar, 150 Orang Gelam and other Orang Laut, 20 to 30 Malays and about the same number of Chinese. But Raffles moved fast. Within days of landing, he had concluded the Singapore Treaty with the local rulers to secure rights for a British trading post in Singapore. By 1824, Singapore and its surrounding islands had been ceded to the British East India Company and subsumed under the rule of the Straits Settlement government, founded in 1786 by Sir Francis Light and based in Penang at that time.

In Raffles’ retinue in 1819 was a detachment of European and Indian troops and their accompanying doctor, young sub-assistant surgeon Thomas Prendergast. By most accounts, western medicine is said to have arrived in Singapore in the person of Prendergast, given his responsibility for the health of the expedition.

True to Raffles’ vision, Singapore grew rapidly. Western medical care in the early decades of Singapore’s founding was administered by doctors in military hospitals for the troops. Local inhabitants and immigrants sought treatment from their traditional doctors and healers. Prendergast, as the military doctor for the troops, was put in charge of the first General Hospital. This was the predecessor of today’s Singapore General Hospital (but little more than a shed then) erected near the junction of Bras Basah Road and Stamford Road in 1821.

Medical services were also strictly segregated along economic and social status, a result of prevailing discrimination. The General Hospital was the preserve of European soldiers, sepoys (Indian soldiers) and the colonial government. The medical staff was made up of military doctors, consisting of an assistant surgeon and an assistant apothecary, assisted by a few medical subordinates. Nursing, if it could be called that, was usually the work of convicts, who clanked around the wards in their chains.

Government officials and the European community were luckier. They were treated in their homes by surgeons sent from the General Hospital. If they were very ill, they were treated in the homes of the surgeons. But in the early years, there was no hospital for civilians such as sailors who were not part of the colonial military establishment. Nor was there one for the local inhabitants.

At the time, diseases such as cholera, smallpox, enteric fevers, typhoid and venereal diseases were common. And treatment was rudimentary at best: Hospitals were often dilapidated, had few beds and suffered from chronic shortage of trained staff. Medical officers were posted from India, the seat of the colonial government, and since Singapore was then regarded as a backwater, such postings were dreaded as hardship assignments. Not surprisingly, few came willingly.

Even for the elites, a stay at the General Hospital was fraught with its own dangers. In addition to less than sanitary conditions, a shortage of staff meant convicts were pressed into service as nurses, orderlies and dressers. As one diary entry described it: “The local convicts are invariably in chains, the clanking of the irons about the ward is sometimes severely felt by the weak and seriously indisposed patients.”

It was not until 1821 that the local inhabitants and immigrants got their own hospitals, or more accurately, buildings being used as hospitals. And even so, the names of these hospitals reflected the prevailing convention of the day. They were known as hospitals for natives, convicts or paupers, or for the mentally ill, lunatic asylums.

Under these conditions, necessity being the mother of invention, private medical care found a foothold. Records showed that two enterprising European doctors set up their own private hospitals in the 1820s but, as charges were high, only the well-heeled could afford them.

As trade passing through the port continued to grow, so did the number of Europeans, sailors, coolies and immigrants from the surrounding countries. This, in turn, led to growing demand for healthcare. Senior hospital administrators, struggling to cope with demand amidst poor conditions, kept highlighting the deplorable state of healthcare for the growing civilian population to the colonial government. However, the latter, based in faraway Bengal in India repeatedly rejected proposals to build a general hospital for Europeans and sailors.

Ships’ captains were especially vocal in their demand for medical services for sick crew members whom they brought ashore for treatment. The captains often rented houses where they could treat their sick crew members, sometimes even leaving them behind when the ships continued on their voyage.

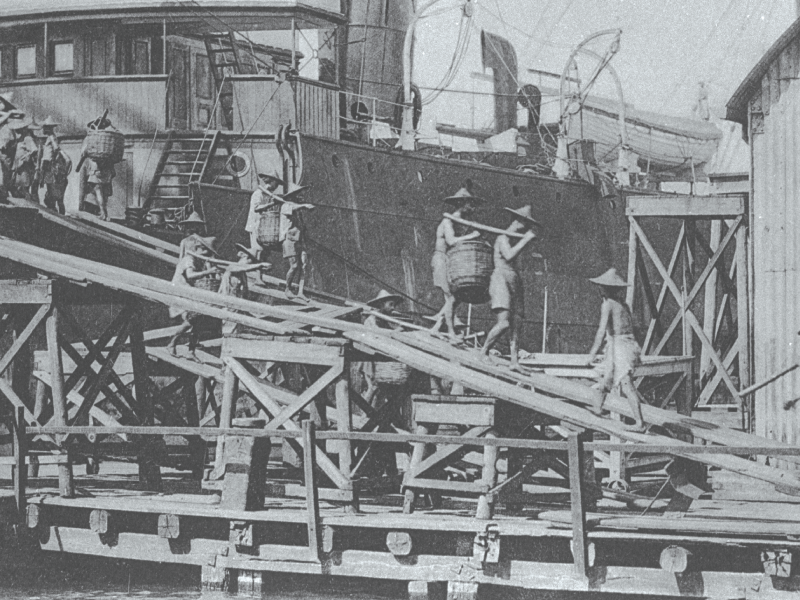

Trading places… as trade grew and more ships docked at Singapore, the captains of the vessels started seeking medical treatment for crew members who were unwell or injured.

The general hospitals have a colourful history of their own. According to the Straits Settlements records, the shed that stood as the first General Hospital in 1821 was replaced by a second in 1822 but the latter “fell down” in February 1827 “on account of the decay of the temporary materials with which it was originally constructed”. A directive to build a new hospital “with every regard to economy” was issued. This was apparently obeyed to the letter because the new hospital was in a state of disrepair by 1830, barely two years after it opened. It was described as dilapidated and full of holes, impossible to stay at when it rained and was eventually abandoned.

In 1831, the new Assistant Surgeon, Dr Thomas Oxley, arrived and proposed that a new general hospital for Europeans and locals be built. But it was not until 15 March 1843 that the colonial government, which regarded Singapore as a financial burden and kept a tight lid on its budget, sanctioned the building of the fourth general hospital. Called the Seamen’s Hospital, it was built at Pearl’s Hill and opened in 1845.

A decade later, a fifth move would take the General Hospital to the Kandang Kerbau district. Its given name, reflecting the patients it served, was the European Seamen’s and Police Hospital; it also took in female patients for gynaecological issues from 1865.

An outbreak of cholera in the area in 1873 forced a temporary move to Sepoy Lines. What was intended as a temporary site became its permanent home when the sixth General Hospital was built and opened in 1882. The site at Outram Road was deemed ideal – on a hill and open to the prevailing breezes, with good drainage and water supply, and near town.

Around the mid-1880s, Singapore was also looking to add female nurses to its healthcare workforce. Despite requests as early as in 1856, when the hospitals were beginning to take in female patients, it was only in January 1867 that approval was granted by the colonial administration. Singapore’s first female nurse had an onerous workload, working in the lunatic asylum while also attending to patients in the nearby General Hospital. For all this, she was paid 22 rupees a month. (Rupees and Spanish dollars were both legal tender at the time. The rate of exchange was roughly two rupees to a dollar.)

However it would not be until 1 August 1885, the day when nuns from the local French convent began to care for the sick in the General Hospital in Sepoy Lines, that nursing really made its presence felt. For that reason, Singapore celebrates Nurses’ Day on 1 August each year and exemplary nurses receive the prestigious President’s Award from Singapore’s head of state.

Medical services

for natives, convicts and lunatics

The Singapore of the early decades was a desperate place. Graphic descriptions in the Singapore Free Press and the then newly-founded The Straits Times painted a picture of poverty, destitution, beggars on the streets, petty crime and opium addiction, among other social ills.

Immigrants flocked here in search of jobs and a better life. Many of them found themselves penniless and jobless, victims of illness and disease. Many turned to crime to support themselves, and to opium for solace.

In June 1821, the first Pauper Hospital was opened in the cantonment. Funds to operate the hospital were low, as the Governor refused to raise the budget to run the hospital. He felt the Chinese community should help pay for treating their own, especially the poor, since the beggars among them represented a growing social problem.

Without contributions forthcoming to keep it running, the hospital was ordered closed. A stay of execution came in the form of the Pork Farm Tax. As the Chinese community was the major consumer of pork, the monopoly of slaughtering pigs and selling pork was auctioned off and revenue from it was used to run the hospital. But the tax was abolished in 1837 on the order of the Governor-General of the Straits Settlements who

Smoke screen… the use of opium to overcome hardships led to addiction which, in turn, added to the many social ills.

was based in India and unfamiliar with the situation on the ground in Singapore. Very soon, the ill and sick, beggars and vagrants began to fill the streets again.

The problem was compounded by increasing arrivals from China due to political upheavals there, as well as sick Chinese labourers from the Dutch colonies who were secretly dumped from their ships at night.

An editorial in the The Straits Times of 23 September 1845 described the situation thus: “It is now more than 25 years since the first formation of the Settlement of Singapore, but still up to this hour no provision is made for the poor, asylum for the sick, no refuge for the destitute. The increase of crime is dilated on, its growing evil lamented but no eye pities, no hand is outstretched to help the poor.”

It goes on: “Most of the streets, bridges, passages of the Town and place of public resort are thronged with miserable objects whose diseased and shattered frames strike horror to the heart… their forlorn situation is no crime… no fund exists from whence their necessities may be relieved and the evil complained of remedied.”

The Straits Times also stated that, of the 36,000 Chinese inhabitants in Singapore, about one third had no visible means of support. It quoted police figures to show that nearly 6,000 were close to starvation, with more than 100 succumbing to it each year.

Still the government felt that the Chinese should take care of their own. In 1843, a wealthy Hokkien merchant, land owner, entrepreneur and philanthropist named Tan Tock Sing (modern day usage spells it as “Seng”)

Signed, sealed and delivered… in 1843, wealthy Hokkien merchant Tan Tock Sing (his name was changed to Seng in the 1950s) pledged $5,000 for a hospital to cater to the local Chinese population via a letter (above) bearing his signature and stamp.

offered to donate $5,000 to the construction of the new Pauper Hospital. When approached for his views on the matter, he pledged the sum in a historic letter to Lt Colonel Butterworth, CB, then governor of Prince of Wales Island (Penang), Singapore and Malacca. Various sums were also pledged by other Chinese, among them 2,000 Spanish dollars bequeathed by the wealthy Chan Cheng San (also known as Cham Chan Sang in some records) in his will soon after Tan’s donation.

As a result of these efforts, the foundation stone for the Pauper Hospital was laid on 25 July 1844 in Pearl’s Hill, just days after the nearby Seamen’s Hospital (the fourth General Hospital) got its own foundation stone. As Tan Tock Sing declared, in his letter officially handing over the Pauper Hospital building to the colonial government dated 21 March 1846, it was intended “for the reception and relief of sick, destitute, diseased and decrepit persons of all classes in Singapore who are unable to earn a livelihood or to obtain the means of subsistence except by public begging in the streets”. The building was ready in 1847.

It is noteworthy that Tan Tock Sing and his fellow philanthropists did not exclude anyone in need from admission to the Pauper Hospital, which the locals called Tan Tock Sing’s Hospital (from the 1950s, it was referred to as Tan Tock Seng Hospital). However, while Tan provided the bulk of the money to build the hospital, a shortage of funds meant it could not operate and paupers were still housed in a rickety shed at the foot of Pearl’s Hill until Mother Nature played her part. The shed was destroyed by a violent storm, forcing the move into the Pauper Hospital premises in October 1849.

It is also interesting to note from Tan Tock Sing’s letters to the government that the hospital was intended to keep vagrants off the streets, not solely for the sick. The government contributed

Mix of people… cultural and language differences among the people in early Singapore made it tough for doctors to do their job.

medicines but not funds and there was no concerted effort to fight the prevalent diseases of the day, such as fevers, dysentery, malaria, smallpox, rheumatism, venereal disease and tuberculosis.

It would take the vision and generosity of other early pioneers like Tan Kim Ching, Tan Teck Guan (the son and grandson of Tan Tock Sing respectively), Tan Jiak Kim (unrelated to Tan Tock Sing), Wee Boon Teck and Loke Yew to use their influence and financial support to build more hospitals for the natives in later years.

While the number of hospitals grew slowly, and their sturdiness to withstand the elements improved, early hospital administrators wrestled with the problem of finding medical expertise and staff. Economy was the watchword of the day. Even the General Hospital, the preserve of the colonial administration, was run on a very tight budget. According to the Straits Settlement records of 1866, it used old bed sheets as bath towels until August that year when permission was given for the purchase of “four dozen bathing towels at a cost not exceeding $20”. In the hospitals for the natives, patients were allowed to wear their own clothing but the condition of their clothes was often “in so bad a state from dirt so as to be detrimental to their recovery”. Treatment costs had to be raised from 10.5 cents per day to 16 cents in November 1866 to raise money to supply patients with clothing and bedding.

Early Singapore’s first doctors faced their share of problems too. Many of them were posted from Britain and India, often military doctors who arrived with their regiments, and they grappled with issues of cultural and language differences.

The doctors found many strange tongues, habits and customs among their patients. Not only did the Chinese speak many different dialects, the Malays, Siamese, Burmese, Bugis, Javanese, Arabs and many more immigrants added to the mix of languages.

However, despite more doctors arriving, the shortage of medical personnel continued due to the increase in population. With growing numbers of people came diseases. Cholera, smallpox and dysentery outbreaks were common, as was tuberculosis. Vagrants, beggars and the sick lined the streets, with no right to seek treatment at the general hospitals and too poor to pay for their native services. This led to growing calls to train locals to ensure adequate medical workers.

Early medical education

in the colonies

Until 1832, the Medical Department for the Straits Settlement was based in Penang, the capital. When the capital moved to Singapore in 1832, the Medical Department followed in 1835.

Medical services were rudimentary at best. Although there was a Senior Surgeon in Penang, he was assisted by medical subordinates, who functioned as military and civil medical officers. Often, the Governor had to order military doctors to attend to patients in civil hospitals.

A 1978 book titled The Medical History of Early Singapore repeatedly mentioned the constant shortage of medical staff. To alleviate the problem, a proposal was put up to train selected local boys as medical assistants, or apothecaries. But the pay was low and the work very demanding.

When the Senior Surgeon in 1822 submitted a plan to the Governor to train selected students from the Penang Free School as apprentices, with a five-year bond, the proposed salary was $6 per month while undergoing tuition. When they were qualified to perform their duties as apprentice apothecaries, they were paid $10 per month. To compound matters, the training was so hard that, of the four original trainees, one dropped out and one ran away. In 1825, the remaining two qualified and received a 50 percent pay rise… to $15 per month!

Not surprisingly, it was hard to get potential trainees to enrol. An excerpt from The Medical History of Early Singapore detailing the duties of an assistant apothecary is self explanatory: “He is placed in charge of the medicines at the Convict Hospital, from which the Native Pauper Hospital, Lunatic Asylum and Jails are also supplied. He has to attend to the Surgeon when he visits the Hospitals, take down notes of any important case, register the prescriptions, see to the medicines compounded, superintend the Dressers, register the names etc. of all the patients who come to hospital, enter their details and draw out returns for them all. Lastly, he must be a person who is able to maintain strict discipline in the hospitals, which is sometimes no easy matter, particularly in the Convict Hospitals.”

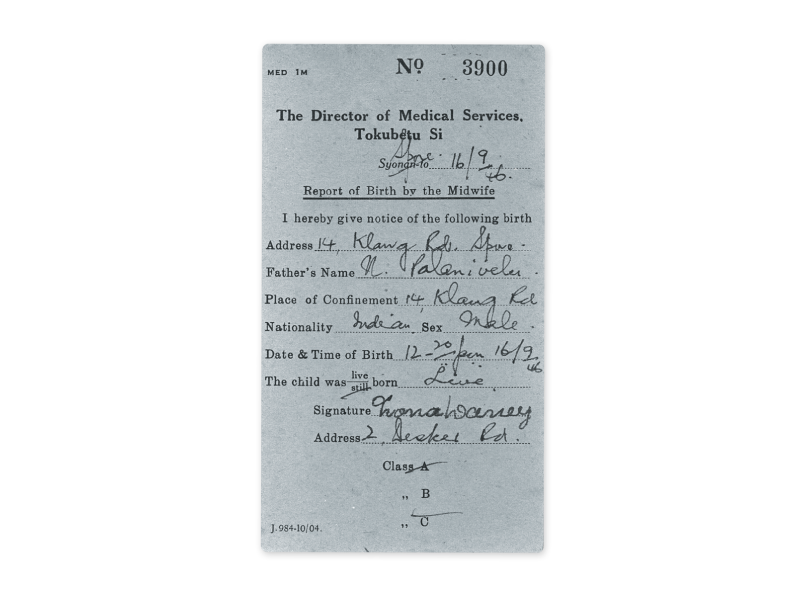

A midwife’s birth report made to the Director of Medical Services or Tokubetu Si in 1946. It still referred to Singapore as “Syonan-to” despite an official ban by the British Military Administration on the name in October 1945 after the Japanese Occupation ended.

Nor was medicine then an attractive career path. The treatment of medical officers, as described in the book, was shabby, with “no organised teaching, no promotion prospects, and no provision made for them on retirement. Boys were not keen to join and those in the service were always tempted to leave for better prospects in the private sector”.

A good example was the first Chinese candidate to be taken on as a medical apprentice in September 1854 under the assistant surgeon in the Pauper Hospital. He resigned because he could not live on the salary.

Singapore’s medical services continued to rely on postings of officers from Britain and India through the 1800s, although a few hardy local young men did apply for training. Various attempts were made through the decades by various officials to raise salaries to entice either local candidates to enrol for training or for officers to accept postings from India, to not much avail.

It was not until 1870 that three local young men were considered fit to be sent to the Madras Medical College for training to become assistant surgeons, with the promise of better pay – a monthly sum of $45 with an increase of $10 every three years until a maximum of $120 was reached. The training carried a 15-year bond. However, only a few – two or three – were sent at any time.

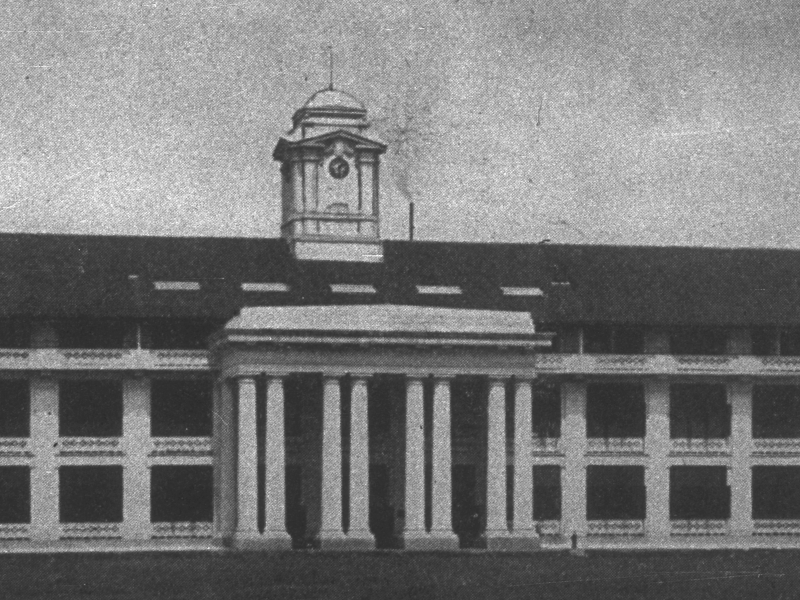

Chipping in… local merchants like Tan Jiak Kim (right) raised the then princely sum of $87,000 to set up Singapore’s first medical school. In 1905, the Female Lunatic Asylum (above) was converted into classrooms but, in 1911, the medical school had a new home: The Tan Teck Guan Building.

But as trade grew, and with it the economy of Singapore, so did momentum pick up in the building of hospitals – sturdier and with more facilities than their predecessors – and the training of local men to be doctors.

But it would be a long wait, to the turn of the century, before Singapore would have its own medical training facility. Led by leading local merchants and philanthropists such as Tan Jiak Kim (Jiak Kim Street is named after him while the adjacent Kim Seng Road is named after his grandfather Tan Kim Seng), the local community raised the then princely sum of $87,000 for the establishment of a medical school. Following a successful petition to the Governor-General in India, this money was used to convert the Female Lunatic Asylum at Sepoy Lines into classrooms and laboratories.

Thus, on 28 September 1905, the Straits and Federated Malay States Government Medical School, the predecessor of today’s Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine in the National University of Singapore, was officially opened. The inaugural intake enrolled 23 students – nine Chinese, six Eurasians, five Tamils and one Malay, one Ceylonese and one European.

Six years later, in 1911, the medical school finally

had a new home, the Tan Teck Guan Building. It was built from funds donated by rubber tycoon and philanthropist Tan Chay Yan in memory of his father, Tan Teck Guan, the third son of Tan Tock Seng. The school’s name was changed to the King Edward Vll Medical School on 18 November 1913, to recognise a large donation from the King Edward Vll Memorial Fund. In 1921, it was changed again to the King Edward Vll College of Medicine.

Meanwhile, a new college building was planned. On 15 February 1926, the College of Medicine Building at the junction of College Road and MacAlister Road was opened. In the following decades, the College of Medicine Building and Tan Teck Guan Building served as the main tertiary institution of medical education in Singapore. Both buildings are now used as the offices of the Ministry of Health (MOH) and are preserved as national monuments.

Early foundations

of public healthcare

In 1843, approval was given to build the fourth general hospital on Pearl’s Hill, a stone’s throw from the site of the first Tan Tock Sing’s Hospital for paupers. The project was financed by the government and the local community, a growing reflection of the wealth and status of the latter, and opened its doors in 1845. This hospital was even asked to admit mental patients from the European community, even though it was not designed to handle such cases.

In 1860, Pearl’s Hill was commandeered for military use by the colonial government. The General Hospital was relocated to the Kandang Kerbau area, its fifth iteration, and was known as the European Seamen’s and Police Hospital. It provided treatment for seamen, the police force and female patients (gynaecological complaints and childbirth). Wards were still set up along the lines of gender and economic status rather than treatment for specific diseases. According to the Straits Settlements records of 1864, the site was not ideal, as it was on low ground “near one of the most objectionable creeks” (the present day Rochor and Bukit Timah canals).

Taking care of the men…a male ward with mosquito curtains at Tan Tock Seng Hospital when it moved to Moulmein Road in 1909.

An outbreak of cholera in 1873 triggered a temporary move to Sepoy Lines, which eventually became the permanent site for the sixth General Hospital, officially opened in 1882. The hospital would be rebuilt extensively in 1926, and officially opened by then Governor Sir Lawrence Nunns Guillemard.

Meanwhile, the Pauper Hospital at Pearl’s Hill had started taking in patients in 1849 to treat widespread dysentery, malaria, tuberculosis and smallpox amongst the growing local population. When Pearl’s Hill was commandeered, it too moved to a new site at the junction of Serangoon Road and Balestier Road.

The first maternity hospital was built in 1888 at Victoria Street, the predecessor to today’s KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

By the turn of the 20th century, Singapore had become a crown jewel of the British Empire, a bustling trading centre and bastion of its power in the East. Such was its importance that the island merited a visit from King George V and Queen Mary in 1901. By 1904, Singapore was the world’s seventh busiest port.

Infection control… Middleton Hospital was built in 1907 to treat patients with infectious diseases.

Transformation of a General Hospital…

1821: Singapore’s first General Hospital started out as a humble wooden shed near Bras Basah Road and Stamford Road.

1822: The hospital moved away from its original site to one closer to the barracks.

1828: Following the collapse of the hospital building in February 1827, a new General Hospital was constructed. Built on a tight budget, the hospital was already in a state of serious disrepair barely two years after it was opened.

1845: After much delay, plans for a new hospital at Pearl’s Hill finally materialised. It was now named the Seamen’s Hospital (right, top).

1860: As Pearl’s Hill was commandeered for millitary needs, the hospital moved to the Kandang Kerbau district. However, a cholera outbreak in 1873 triggered a temporary move to Sepoy Lines (right, second from top).

1882: Sepoy Lines, now known as Outram Road, eventually became the permanent location of the General Hospital which opened this year (right, second from bottom).

1926: The hospital was rebuilt extensively and officially opened as Singapore General Hospital (right, bottom).

But the health of the population in the pre-war years continued to lag behind Singapore’s burgeoning growth. The prevailing diseases then – malaria, venereal disease, tuberculosis, beriberi, pneumonia, enteric fever and ankylostomiasis, or hookworm disease – continued to plague the people. Infant mortality was high and patients were still being admitted to hospitals on the basis of their economic status.

The huge disparity in pay for officers in the two medical services – one for Europeans and one for locals – continued to co-exist and cause unhappiness among the local officers. The late Professor Ernest Steven Monteiro, who served as the Director of Middleton Hospital for Infectious Diseases during the Japanese Occupation and later as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at University of Malaya (1956–1960), spoke about this in May 1985 interview with the Oral History Centre of the National Archives.

He recalled that “an expatriate medical officer would be drawing $850. A local graduate would draw $250. Of course he had annual increments. He was gradually given more salary as the years went by. But the strange thing is that these two services remained apart and caused quite a lot of feelings among the local doctors who all the time thought they were just as good as the expatriates, especially those recruited from England, raw recruits from the Irish universities who had no experience and just dumped into Singapore”.

However, despite the public healthcare system still lacking a systematic approach to the development of hospitals and medical services, a nucleus had begun to take shape.

Most of today’s public hospitals were built or rebuilt before the Second World War. In 1907, the predecessor to Middleton Hospital was built as a quarantine camp for infectious diseases. It was relocated to Moulmein Road in 1913 as the Government Infectious Disease Hospital and renamed Middleton Hospital in 1920 after Dr W.R.C. Middleton to recognise his 27 years of work in infectious diseases.

The Pauper Hospital was also on the move because the swampy site was deemed unhealthy for patients. Construction at its current site at Moulmein Road began in 1905 and the hospital moved in in 1909.

Kandang Kerbau Hospital moved to Kampong Java Road from its Victoria Street site in 1924. (In 1997, it moved across the road and was renamed KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

Ending discrimination… in the early years, patients were warded according to their economic or social status, not their medical condition. From 1946, the Unit System saw all medical and surgical wards divided into units under the care of their specialists and patients were given equal treatment.

Its former site now houses the offices of the Land Transport Authority). The General Hospital at Sepoy Lines was rebuilt and opened on 29 March 1926 as the Singapore General Hospital, its seventh iteration.

A lunatic asylum called the Mental Hospital was built in 1928 to treat and house psychiatric cases; in 1951, it was renamed Woodbridge Hospital. In 1993, it moved from its Yio Chu Kang premises to a new building at Hougang and is now called the Institute of Mental Health. The Royal Air Force Hospital (the predecessor of today’s Changi General Hospital) opened in 1935 and the British Military Hospital (the predecessor of today’s Alexandra Hospital) was established in 1938.

Middle Road Hospital was set up in 1945 to deal with sexually transmitted diseases and later to also manage skin conditions. Thomson Road Hospital, the last of the pre-independent Singapore hospitals, was built and opened in 1959.

Significantly, it was the opening of the extensively rebuilt Singapore General Hospital in 1926 that marked a watershed in the structuring of Singapore’s medical services. The new hospital had few antecedents. It had 800 beds in three blocks, which housed first, second and third class male and female wards, as well as a children’s ward. It also had operating theatres, a pathology laboratory, kitchen facilities, an outpatient block and living quarters for nurses.

It broke completely from caring only for seamen and the police to providing modern medical care to the local people, regardless of race or social background. For the first time, the local people, or natives, had access to government-run health facilities.

But the hospital was still far from perfect. Patients were still assigned to wards based on gender and economic status rather than grouped for specific illness or disease; the distance between the three blocks meant doctors were often delayed in attending to their patients. The small number of doctors then made specialisation difficult, although some doctors developed expertise in specific diseases out of interest and the large patient load. The first record of a specialist appointment was of Dr G.A. Finlayson, as government pathologist for all Singapore hospitals in 1906. He also made significant contributions to the teaching of medical students in the Medical School until his retirement in August 1926.

The fight

against disease

In the 1800s and early 1900s, cholera pandemics were common in Singapore, each lasting many years – one outbreak lasted 24 years, from 1899 to 1923; 2,693 deaths were recorded between 1900 and 1920. Before the 1900s, malaria was uncontrolled and it was not until the 1950s that indigenous malaria disappeared from Singapore. Smallpox outbreaks were common too, as was human plague, brought ashore by rats and fleas from ships calling at the harbour. A death rate of 88 percent from plague was recorded between 1900 and 1930.

Public health measures to fight these diseases were two-pronged – quarantine and vaccination. For example, quarantine facilities were set up at St John’s Island for those affected by smallpox and vaccinations and immunisation programmes were carried out for smallpox, cholera, polio and diphtheria.

Progress was made, although these efforts were often hampered by “inadequate facilities, shortage of trained staff and strong opposition from the shipping community”, in the words of Professor Goh Kee Tai, Senior Consultant in the Office of the Director of Medical Services, Ministry of Health, and an expert in epidemiology and infectious disease. In his study, he also pointed out that “different quarantine requirements by different countries and utter ignorance of the aetiology and epidemiology of diseases resulted in considerable difficulties, sometimes insurmountable barrier to free transit of goods and people”.

Coupled with the growth in population as trade flourished, Singapore was in need of primary healthcare. Many immigrants who had come to Singapore in the early 1990s had taken up farming in the rural areas to support themselves and their families. The lack of personal or public transport in these areas made it difficult for people to get to the hospitals for treatment, even if they could afford it. Healthcare providers showed doughty ingenuity in providing solutions: Outpatient dispensaries took healthcare to those living in rural areas like Sembawang, Bukit Timah and Choa Chu Kang.

In 1910, the first outpatient dispensary was opened in South Canal Road and expanded slowly to other areas – the next one opened in Paya Lebar in 1923. The creation of the Government Travelling Dispensary in 1930, set up at the urging of Singapore’s first public health nurse Miss Ida M.M. Simmons, greatly extended the reach of primary healthcare services to the rural and outlying areas where malnutrition led to postnatal beriberi and common childhood diseases. The service was launched with weekly sessions at the Bukit Timah Government Outpatient Dispensary,

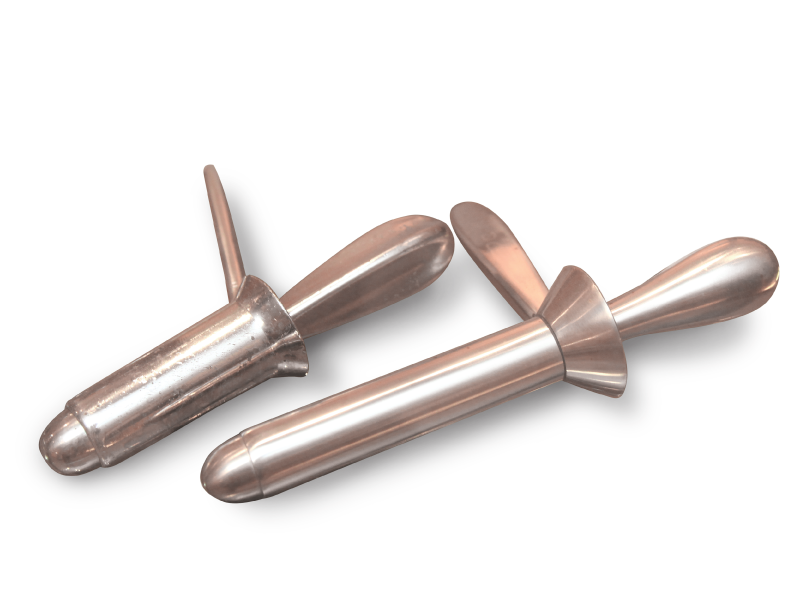

An early stainless steel proctoscope used by doctors for rectal examinations.

Not the most comfortable topic, but proctoscopy — a common medical procedure to examine the anal cavity, rectum or sigmoid colon for hemorrhoids or rectal polyps — used to be done with stainless steel proctoscopes in the early days. Today, fibre-optic proctoscopes make the procedure less daunting.

and other dispensary centres were set up in shophouses and temples all over Singapore.

Simultaneously, attention had also turned to reducing the high rate of infant mortality. As early as 1907, the colonial government began setting up registration and treatment centres from which midwives could be dispatched to deliver babies for mothers who could not afford such services and also to give advice on childcare. This effort to provide better maternal care for local women soon became the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Service.

The service, run largely by nurses, saw house-to-house visits begin in 1910. By 1923, the first MCH clinic was set up as a vaccination centre in Prinsep Street. As smallpox vaccination was compulsory, parents who took their children to the clinic received advice on childcare while the babies were also weighed and checked for growth issues or abnormalities.

Within the next year, Chinatown, which had a high birth rate, got the Kreta Ayer MCH centre which was set up in the converted Rickshaw Station now known as the Jinriksha Station. In 1931, the Joo Chiat clinic was set up to serve Geylang, which had a higher concentration of Malays.

In the rural areas, there were no permanent clinics. Most villages and roads had no names then, and nurses trudged down footpaths and muddy roads which were often little more than bullock cart tracks – lugging their bags of records and equipment to deliver service, often in people’s homes and even by the roadside. Occasionally, they even had to clamber into sampans to reach the outer islands.

The first full-time doctor for the city clinics was hired in the 1930s and the first one for the rural service in 1949. By 1958, there were 13 new clinics for the rural areas. Dr Irene Pakshong, Medical Director of the MCH from 1968 to 1985, remembers working in the Alexandra Road clinic where “there were pigs walking around” the premises.

The Dental Clinic was built in 1938 to provide dental services to the public and government servants.

Occupation degradation… the Second World War saw Japanese forces destroy much of the pre-war progress made so far. An air raid left a row of shophouses in Chinatown in ruins (right) while patients and nurses were left shaken after the British Military Hospital suffered similar damage (above).

By the 1940s, medical care in Singapore had undergone a sea change compared to the previous century. The introduction of national health schemes worked in tandem with public health and sanitation measures such as anti-malaria work, sewage and refuse disposal and maintenance of the water supply to improve the health of the population.

The Second World War, from 1942 to 1945, brought this promising momentum to a screeching halt. The war wreaked havoc on the population and on medical services, severely straining manpower and medical supplies. As a result, the civilian population suffered from severe malnutrition and conditions associated with it, like beriberi, were widespread. Malaria was rampant too.

The Occupation destroyed much of the progress made in the preceding 40 years. The Japanese forces commandeered the hospitals for their use, taking over the General Hospital on 18 February 1942 and turning it into the Occupation’s main surgical hospital for its troops in Southeast Asia, along with the Mental Hospital and Alexandra Military Hospital. Kandang Kerbau Hospital and Tan Tock Seng Hospital became the main civilian hospitals. The medical school at the College of Medicine Building was closed on 16 February 1942 and the building occupied by the Japanese Army Medical Corps. A medical school was set up in Malacca.

Many died, from bombs and bullets as well as other consequences of war. A cut in water supply to the General Hospital was disastrous. The hospital buried hundreds of the resulting dead in a mass grave on its grounds. A Japanese air raid killed a group of 11 students who had gathered to dig the grave of a student killed a day earlier at the Tan Tock Seng Hospital dormitory, where he had been on attachment. The bronze plaque commemorating them is still seen in the lobby of the College of Medicine Building today. Postwar, three blocks in the General Hospital were named the Bowyer, Stanley and Norris Blocks to commemorate doctors who died in the war. Only the Bowyer Block still stands as the other two had to eventually make way for hospital expansion.

Once the Japanese left, the British Military Administration faced the enormous yet urgent task of healing the tears in the fabric of Singapore’s

Metal memory of mettle… this bronze plaque in the lobby of the College of Medicine Building (the current location of the Ministry of Health) honours the 11 students who lost their lives during a Japanese air raid on 14 February 1942 even as they dug a grave for a student who had been killed a day earlier.

Midwives in the making… happy faces outside the midwifery school at Kandang Kerbau Hospital in the 1960s.

public health services. Primary healthcare – outpatient, maternal and child health and the school health service – was given top priority. But it was not enough.

A 10-year Medical Plan to improve Singapore’s health and medical services was approved by the Legislative Council in 1948. Implementation began in 1951, with existing hospitals expanded and modernised, while many new outpatient clinics, maternal and child welfare clinics and infant welfare clinics were built. In the meantime, a Nursing Ordinance came into force in 1949 to regulate the registration, training and professional discipline of nurses, while a Medical Registration Ordinance was enacted in 1953, making housemanship compulsory for doctors.

In 1955, the General Hospital’s Paediatric Unit was moved to the Mistri Wing, named after the donor Mr N.R. Mistri. In 1956, the new School of Nursing in Sepoy Lines was opened to train more nurses for the expanding medical services.

In 1958, the Institute of Health was founded, housing all the preventive health services for children under one roof. In 1959, the year Singapore attained self government, Thomson Road Hospital (later renamed Toa Payoh Hospital) was converted from treating the chronic sick to dealing with more serious health issues.

Self-governing Singapore inherited the host of public health problems resulting from high population growth, overcrowding, industrialisation, poor food hygiene, vector-borne diseases and poor sanitation. For the first Minister for Health, Mr Ahmad bin Ibrahim, after whom Jalan Ahmad Ibrahim is named, and his successors, these problems persisted well into the 1960s and beyond. On a positive note, the tenure of these able men marked the beginning of reorganisation and consolidation in healthcare services for the fledgling nation.

Special treat… Franciscan nuns and nurses taking tuberculosis patients for a boat ride in the 1950s.

Tuberculosis, the major cause of death in 1940s, continued to be a problem well into the 1980s. In 1959, a mass X-ray campaign revealed that one in 27 people were likely to have the disease. Quarantine and vaccination programmes continued against smallpox, diphtheria and polio. In 1959, a mass smallpox vaccination exercise covered 1.1 million people over four weeks. Vaccination against diphtheria had been introduced in 1938 and made compulsory in 1962. With poor public sanitation and food hygiene, cholera outbreaks too were frequent and deadly.

New diseases, aided by greater mobility of people and international travel appeared. In 1957, the Asian flu pandemic swamped medical services – of over 160,000 visits to the government and City Council clinics, 77,211 were for flu. There were 680 deaths among a population of 1,445,900.

Infant mortality was high. In 1959, the infant mortality rate was 36 per 1,000 live births (compared to two in 2013). For a small population of 1.6 million then, there were 63,720 live births but 10,246 deaths. Mothers too frequently died during childbirth. Maternal mortality was 0.7 per 1,000 live and stillbirths (compared to 0.1 between 2001 and 2011).

Statistics showed that in 1959, cancer caused 10 percent of deaths, heart and circulatory system diseases 9.6 percent, pneumonia 9.3 percent, diseases of early infancy 9.0 percent, tuberculosis 6.1 percent and stroke 4.7 percent.

Even these dire numbers were an improvement on the past decades. So much so that Health Minister Ahmad Ibrahim could report in May 1960 that “a great deal has been achieved as the responsibility of the health services increase”.

He added: “In all, $37.5 million was spent in 1959 for health; about $25 per person. The standards achieved must be maintained. And to do this, we must give better training facilities for more of our citizens in the various branches in health. The last year has shown that it is not only possible to maintain standards, but to continue to improve on them steadily.”

And a great deal more needed to be improved.

In a meeting with senior government officials, civil servants, administrators and supervisors connected with the health services, reported in The Straits Times of 14 November 1964, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew painted a stark picture of the state of public health in Singapore. He said: “Singapore is now full of flies. There are many wild dogs and cows running about in the streets, and some of them have been occupying bus shelters as well. The situation looks very grave.”

Fifty years on, in a 31 August 2012 interview with the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), Mr Lee spelt out Singapore’s attributes as a modern first world city: Safety, cleanliness, mobility, spaciousness, connectivity and equity.

But Singapore on the cusp of independence was, in the words of CLC executive director Khoo Teng Chye in a 24 July 2014 interview with The Business Times, “a basket case of urbanisation gone wrong”. Mr Khoo, who had served with the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) from 1976 to 1996, the last four years as its CEO and chief planner, added: “Overcrowding, traffic congestion, flooding, crime, no proper sanitation – name any urban problem and we had it.”

The fight against these challenges would require the coordinated efforts of the Ministry of Health, the Housing and Development Board and the Ministry of the Environment and, later, the URA after independence in 1965.

Waste management… in the early 1800s, night soil carriers carried human waste in buckets slung across their shoulders (inset) and sold it to market gardens and plantations for use as fertiliser. When the first sewerage system was introduced in 1910, the waste was taken to designated night soil disposal stations across the island before it was channelled to treatment plants. If you are wondering why it is called night soil, it is because the waste was collected mainly at night.

Night soil carriers removing latrine buckets from houses. Early Singapore lacked sanitation and diseases spread easily.

“Caring for our People: 50 years of healthcare in Singapore”; reprinted with the kind permission of MOH Holdings Pte Ltd.