The Three Hs of Medicine

Medical technology has advanced by leaps and bounds, but the ethos of medical practice remain constant.

Alumna Dr Wong Hee Ong, who graduated from the University of Malaya, Singapore (former King Edward VII College of Medicine) in 1953, and subsequently taught in the Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya (UM), Kuala Lumpur believes that all doctors should be guided by the 3Hs in the practice of medicine – using their heads, hands and hearts.

The practice of medicine has become technology-driven and many doctors and medical students today tend not to use their senses adequately when they see patients, she asserts. The art of medicine is gradually being overshadowed by technology.

“As students, we were taught to notice how our patients walk and smile, for clues to their diagnosis. I think of Sherlock Holmes: we were taught to use our eyes, ears, hands to examine patients, and to talk to our patients, because very often the patient is telling you the diagnosis. This was also the basis of how we taught our students, which is more educational than didactic lectures”, said Dr Wong, who was Professor of Medicine, UM and Consultant Physician in Kuala Lumpur. Once, she attended to a patient who had weakness in her leg. She asked the woman for more details, examined her, and concluded that she had a brain tumour. Months later, the patient visited her again and said she indeed had a tumour, which was removed in Singapore. The patient admitted that she did not believe the diagnosis and wondered what the brain had to do with the leg. Dr Wong then realised that she should have spent more time to explain to the patient.

“You need to let your patients have the confidence. It is worthwhile spending time to talk to your patients to get a detailed history of their symptoms, examine them carefully so that you get the right provisional diagnosis. Then order the correct tests to confirm your

diagnosis. This will save your patients from having unnecessary tests or taking unnecessary medicines, thus helping to keep healthcare costs down. A good doctor should be empathetic, treating the patient as a whole person, and be aware of the circumstances he is in – the family situation,social economic status – which could relate to his illness. In other words, practise with your head, hands and heart.”

Life in early 1900s

Born in Singapore in 1927, Dr Wong was the fifth child in a family of 10 children.

She was in secondary school when World War II disrupted her studies.

“There were bombs everywhere. I fell ill and almost died, but I recovered,” she said.

At age 14, Dr Wong worked as a cashier in a doctor’s pharmacy. As her wages were meagre, she went from one job to another, learnt the Japanese language and learnt how to operate a Japanese typewriter, which was large and cumbersome. She ended up working for a big Japanese firm typing letters in the Japanese language for the Manager.

After the war ended, she returned to school in 1946 and qualified for medical school at age 19.

“In those days, there were very few career choices – becoming a doctor, a teacher, a nurse or a pharmacist. Since my brother was already in medical school, and all my friends wanted to do medicine, I followed and applied.”.

She was one of three Singaporean girls in her cohort of 80, each selected from the top three girls’ school in Singapore. The remaining seven girls came from Malaya.

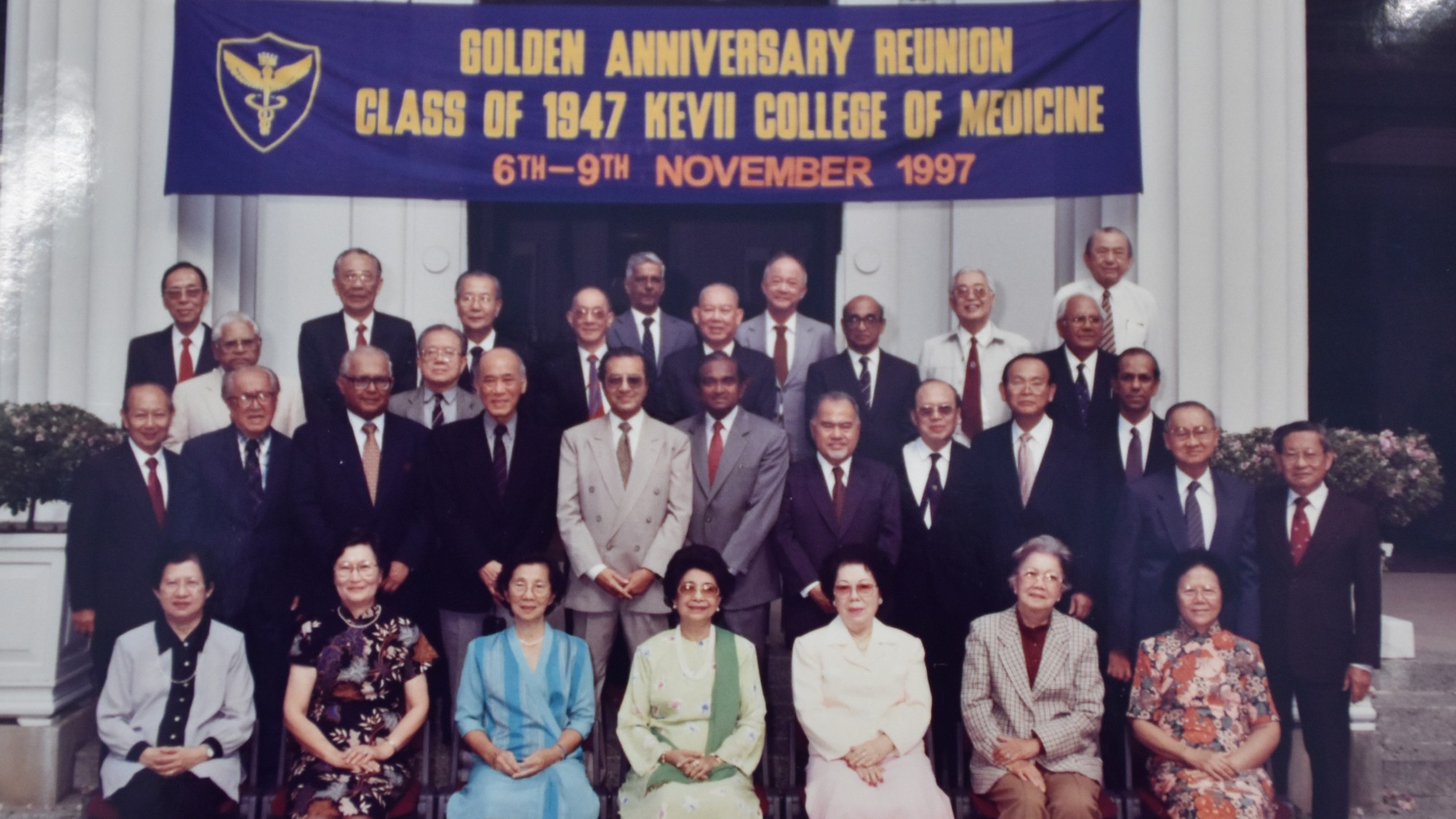

Dr Wong Hee Ong (front row, second from left) and her classmates from King Edward VII College of Medicine at a reunion event in 1997.

A career in teaching and clinical work

Upon graduation in 1953, Dr Wong worked as a medical officer, caring for patients at the general ward of the Singapore General Hospital. She also mentored medical students who visited the ward for their practical bedside studies, and taught them how to deduce the patient’s diagnosis by taking a good history, using their eyes, hands, and thinking logically.

In 1964, the University of Malaya in Singapore decided to set up the Faculty of Medicine in the campus in Kuala Lumpur (KL), and Dr Wong and a few others were sent to help establish the Faculty and the new University Hospital in KL. Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965 but Dr Wong stayed on in KL.

She joined the University of Malaya’s Faculty of Medicine as an associate professor and later became Professor of Medicine and Consultant Physician to the University Hospital. She retired in 1978 after having taught 14 batches of students. Among Dr Wong’s students are psychiatrist Professor Kua Ee Heok and gynaecologist-obstetrician Professor P C Wong, both with the NUH.

“Every time I see my students’ achievements, I feel so happy. As the saying goes I ‘bask in reflected glory’. My happiest moments are to see my students do well. So many of them are professors now,” said Dr Wong, who after retirement went into private practice as a consultant physician and cardiologist in Kuala Lumpur.

In 1992, she was offered the post of Chief Executive Officer to establish Gleneagles Hospital in Kuala Lumpur. The hospital had to be planned and built from the ground. It was a tremendous responsibility but very satisfying as “I learnt a lot about planning a user friendly hospital and all the safety features that should be incorporated into a hospital building”. She later became a Chief Surveyor, on a voluntary basis, for the Malaysian Society of Quality in Health to train hospital staff and accredit hospitals for the Society which is a member of the International Society for Quality in Health.

Active ageing

Dr Wong returned to Singapore in 2010. She attends Chinese classes and lectures as part of lifelong learning and also takes part in the dementia prevention programme called Age Well Every Day, which is run by the National University of Singapore’s Mind-Science Centre.

As part of the programme, Dr Wong trains volunteers to give dementia-related health talks to seniors at various centres in the community. The programme also has music and art therapy, and gardening, as well as mindfulness practice and exercise sessions for seniors.

“Getting involved in this dementia prevention programme helps me from developing dementia. It is good to find something satisfying to do, and have social interaction with others.”

Dr Wong Hee Ong (front row, sixth from left) and her King Edward VII College of Medicine classmates.