A Doctor Never Stops learning

MEDICAL education is one of my passions. When I became a doctor in the 1950s, education was very well structured in Singapore’s medical school. However, for specialist training we were dependent on medical institutions overseas, especially in the United Kingdom. Doctors had to go there to get higher qualifications. Some went for a year, two years or even three years; that meant a loss of manpower and finance to Singapore. It took Dr Toh Chin Chye to change all that.

Many doctors, especially those of us at the Academy of Medicine (set up in 1957), had been asking for our own specialist qualification system: Something that let doctors work and train in Singapore and only go abroad for hands-on experience. Of course, we knew we needed to have very stringent qualification methods… even better than those in the UK and Australasia.

The Academy of Medicine and the School of Postgraduate Medical Studies spearheaded this move, petitioning the Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Singapore University many times. Nothing much came out of this except for the formation of a committee on postgraduate medical studies in the medical faculty in the mid-1960s.

The situation shifted in October 1967. Dr Toh, who was Deputy Prime Minister at the time, gave a speech where he criticised the medical school and the medical community for not developing postgraduate education and thereby producing specialists. Professor K. Shanmugaratnam, who was the master of the Academy then, immediately called me and said: “Chin Hin, we must respond to Toh Chin Chye.”

We convened an emergency council meeting and drafted a reply to Dr Toh. Soon after that he called us for a meeting at City Hall… I think it was held at the surrender chambers where Lord Mountbatten took the surrender from the Japanese. It was a very cordial meeting. Dr Toh can be a very tough person, but he was very kind to us. He said, “Shanmu, you be the chairman of this committee to spearhead the formal postgraduate medical education programme.”

So that is how the school of postgraduate medical studies came to be shared equally by the medical faculty and the Academy of Medicine. And that is how our first master of medicine degree, the MMed, came about in 1970-71.

One of things we insisted on was that the standards of examination be very stringent. We had to appoint external examiners to ensure that some of the elements would be similar to, if not even better than, the qualifying process in the UK and Australasia. We started with MMed (Internal Medicine) and MMed (Surgery), then MMed (Obstetrics & Gynaecology) and MMed (Paediatrics). We had paediatrics because of Professor Wong Hock Boon.

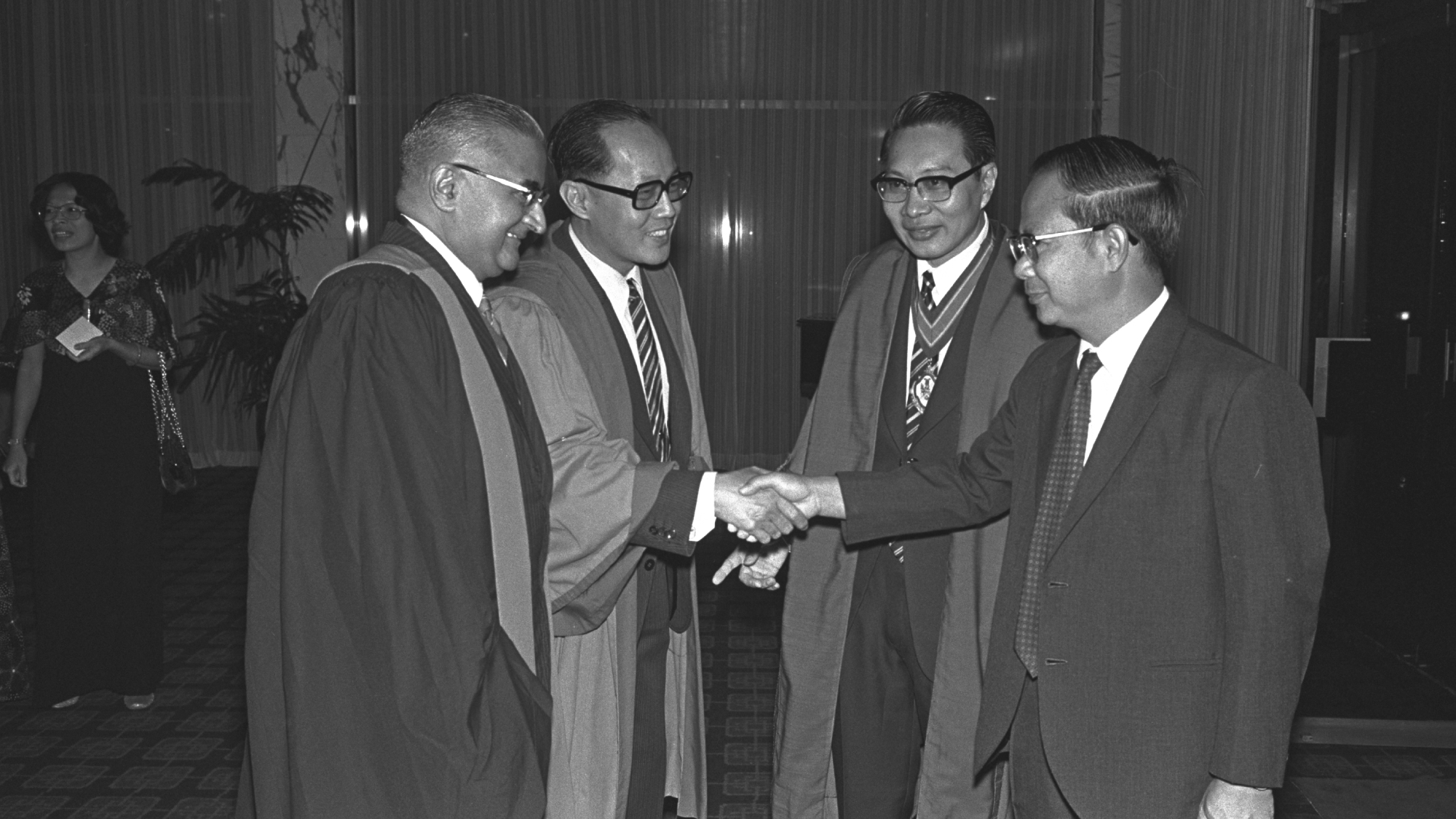

Master of the Academy… Prof Chew (second from right) was part of the welcome party that greeted Health Minister Toh Chin Chye (far right) when he arrived at the 10th Singapore-Malaysia Congress of Medicine in 1975.

Of course, we had our own local examiners to support the external examiners; some were presidents of their respective colleges from the UK and Australasia. We asked the external examiners to give us unbiased reports on our candidates and our examination standards. Invariably, the reports said that both were of very high standards, even higher than in their own countries. And they were so impressed; they even suggested having reciprocal examinations!

The first joint examination we agreed on was the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons together with MMed; that was in the late 1980s. That was a milestone. Our professional standards had been accepted and our

trainees could take the examinations here.

I was then on the board of the School of Postgraduate Medical Studies. In 1991, when I retired from MOH as Deputy Director of Medical Services, I retained my role on the board as deputy director, a post I inherited from Professor Seah Cheng Siang in 1989.

Teaching the doctors has changed a lot since my time, thanks to computerisation and advances in imaging and other technology. Many doctors of today tend to depend on them more. When I started as a young doctor, we always insisted on good bedside teaching and not being dependent on too much investigation. Our old professors like Gordon Ransome could diagnose diseases without much aid. Simple laboratory investigations were crucial to our management, like taking blood samples for malaria parasites. But I think it is very important for young students to have the fundamentals of learning and teaching; to be taught how to be meticulous with patient histories and clinical examination, which can give you quite a lot of knowledge to get the right diagnosis.

Medical training is a lifelong process. A doctor never stops learning and never stops teaching the next generation.

“Caring for our People: 50 years of healthcare in Singapore”; reprinted with the kind permission of MOH Holdings Pte Ltd on behalf of the Ministry of Health.