What Matters for a Good Life Matters for Good Care

By Dr Vikki Entwistle, Professor of Bioethics and Director,

Centre for Biomedical Ethics

In a recent report on Good care at home for older people in Singapore,1 colleagues and collaborators of the Centre for Biomedical Ethics encourage us to consider how, in an ageing society, we should “acknowledge, advance and balance the interests of older adults and of caregivers” (p1). They open the first main section of their report by stating that “A good life and good care are intertwined”, and as they discuss the ethical dimensions of caregiving relationships and the social systems that support them, they emphasise the importance of a good life for both those older people who need care and for the various people (including family members, domestic workers, neighbours and community volunteers) who care for them (p5).

The concept of a good life can be very useful for ethical reasoning, not only about the care that we need and should give each other within our families and communities but also about the care provided by professional health services. After all, what makes healthcare good if it does not improve people’s lives?

Professional discourse about healthcare, however, sometimes seems to reflect and foster somewhat narrow thinking, both about what matters for good lives and about the ways that health services can contribute to good lives. This can tend to limit ethical sensitivity and reasoning about healthcare provision. Perhaps particularly in less urgent and less acute cases, it can constrain the practical pursuit of good care in its most meaningful senses.

In this issue, I briefly consider how we might usefully strengthen efforts to improve healthcare by reinvigorating ideas about the relationships between good care and good lives. More specifically I suggest taking a broad view of the purpose of healthcare as being to enable people to live (and die) well.

Disease-centred, system-centred or person-centred healthcare?

An important set of concerns about the quality and ethics of healthcare relate to patients’ (and sometimes family members’) experiences of not being appropriately treated as persons in healthcare settings. Extreme examples involve people feeling they have been treated as ‘lumps of meat’ or ‘things on a conveyor belt’. More typically, people give examples of disrespectful or uncaring interactions, of not being listened to or taken seriously, of being unfairly judged and of not being able to understand or have a say. Both unduly ‘disease-centred’ and unduly ‘system-centred’ approaches to health care have been identified as tending to contribute to these poor experiences.

The critique of disease-centred healthcare acknowledges that much progress in medicine has been made via the scientific study of disease processes at the levels of physiological systems, organs, tissues, cells and genes, and via the development of sophisticated technologies, including pharmaceuticals, to tackle these. It points out, however, that the potential benefits of the resulting diagnostic and treatment interventions can be significantly undermined if healthcare providers forget that there is more to a good human life than disease control and if they do not refocus clearly enough on what matters to each particular patient as a person.

The critique of system-centred healthcare acknowledges that access to safer and more effective healthcare has been made possible for many people by concerted efforts to study healthcare needs and the effects of potential interventions at the level of populations, and to use the knowledge generated to inform the development of healthcare systems. It points out, however, that the positive potential of this work can be significantly limited if insufficient attention is paid to the particularities of often diverse people within populations or to the ways people feel as they are processed through these systems – to how their experiences of healthcare systems contribute to their sense of how well their lives are going.

The critiques of disease-centred and system-centred healthcare have both underpinned the development of the idea that good healthcare should (among other things) be person-centred. Such care has been defined in various ways, but can be understood generally to promote the idea that good healthcare should treat people ‘as persons’ – including, for example by recognising them as worthy of respect and care, and by appreciating that their own perspectives on their experiences and lives matter.

Quality of life or living (and dying) well?

Talk about how healthcare impacts on people’s ‘quality of life’ suggests a (re)connection is being made between ideas about good care and ideas about good lives. In many healthcare contexts, however, the phrase ‘quality of life’ is associated with a rather narrow set of ideas and standardised assessments of, for example of people’s levels of pain, fatigue and functional ability in domains such as mobility, feeding and self-washing. These can be important indicators of areas in which people might need care, but they can also fall quite a long way short of capturing the range of capabilities and experiences that matter in people’s lives. Some key concerns of person-centred care are absent from much quality of life discourse, and some typical quality of life assessments are insufficient as guides to good care provision or measures of healthcare success.

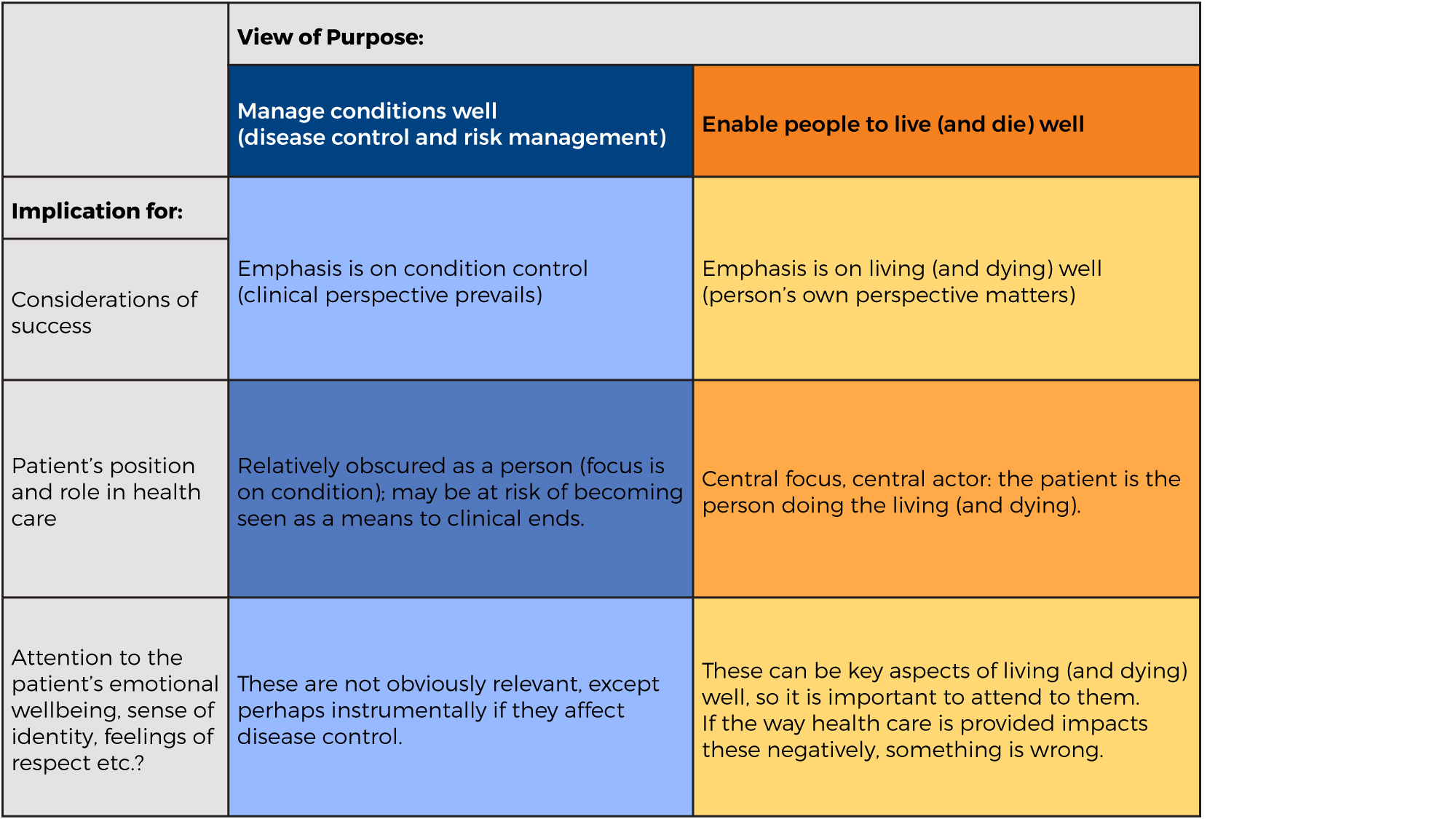

In recent work with colleagues from the UK, I have argued that healthcare for people with long-term health conditions (e.g. asthma, diabetes, Parkinson’s) should be broadly oriented to enable them to live (and die) well with those conditions.2 When contrasted with narrower views of the purpose of health care, and even with a focus on quality of life when that is understood in a static and standardised way, this broader view has a number of advantages. I will mention just a few interlinked points here. First, a focus on enabling people to live (and die) well can bring all aspects of what matters for good lives into the frame of consideration for healthcare decision-making and practice. It can keep disease control in the picture, but it also keeps it in perspective (see figure). It can also accommodate the ambitions associated with person-centred care because, for example, feeling respected and cared for are important aspects of living well. Second, a focus on enabling people to live (and die) well should help to foster the kind of person-centred healthcare practice that many people regard as important features of good care, because consideration of what would enable someone to live (and die) well requires respectful and caring consideration of that particular person’s perspective – we judge our living (and dying) in large part on our own terms. Third, if necessary, this broad view of purpose also encourages us to recognise any ways in which healthcare undermines people’s scope to live (and die) well as harmful – or at least somehow problematic.

A broader view of the purpose of health care: keeping disease control and health promotion efforts in perspective

A promising educational initiative

In another recent Centre for Biomedical Ethics publication, Looking through the silver mirror,3 a group of NUS students show how they developed what we could describe as an appreciation of the broader and more personally specific aspects of living (and dying) well. The students, who are working towards careers in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, psychology and social work, each spent time with an older Singaporean from outside their immediate families, listened to their life story and their experiences with health problems and health and social care, and then reflected on their conversations. In a series of essays, they introduce us to the rich array of characters they met. They convey with deep respect something of what the person they spoke with valued in their lives – both when they were younger and now in their older age. The students acknowledge, often with mature humility, what they learned as they got to know the person as such, including about the ways in which health and social care could impact both positively and negatively on what mattered to them in their lives.

In Looking through the silver mirror, the students show some highly promising sensitivity and creativity as they consider how, in the future, they might integrate appropriate biomedically-based professional considerations (for example about an older person’s physical condition) with attention to each person’s own particular values and aspirations (for example to maintain some independence through work, or to make

other people happy). Their thoughtfulness bodes well for those of us who might need their professional help in coming years. I hope that for the rest of their professional education and in their future work environments these students (and others) will be supported to maintain and share their appreciation that the quality of healthcare should be considered at least in part in terms of the extent to which it enables people to live (and die) well.

References

1. Chin J, Dunn M, Berlinger N, Gusmano M (2017). Good care at home for older people in Singapore. Singapore: Centre for Biomedical Ethics. ISBN: 978-981-11-7509-1

2. Entwistle VA, Cribb A, Owens J. Why health and social care support for people with long-term conditions should be oriented towards enabling them to live well. Health Care Analysis, 2018, 26(1): 48-65.

3. Wong HZG (Ed.) (2018). Looking through the silver mirror. Singapore: Centre for Biomedical Ethics. ISBN: 978-981-11-77734-7