The Sum of All Fears

Life as a new doctor is fraught with risks. It is also stocked with opportunities for personal and professional growth and development. Dr Wong Wen Kai (Class of 2017) shared his experiences and perspectives.

I just graduated from medical school last year, and have been spending my past 10 months working as a House Officer in our public healthcare system. I’m not part of any residency programme, so I can’t offer much in the way of practical advice on how to get your dream specialty.

Instead, today I hope to share on some of the “softer” things about life as a junior doctor.

Becoming a doctor is scary. I’m certain many of you would remember the warnings the admission officers and speakers at the Open Days gave freely when you were considering enrolling as a medical student. If you were like me, you would have just chuckled and put those warnings aside. After all, how bad could it be to be in a well-paying and generally well-respected profession?

And if you were just like me, you’d slowly realise the deep horror of being entrusted with someone’s life shortly after the adrenaline of completing your final exams wears off. Taking that leap to become a clinician is tough. The hours are long, the expectations heavy, and the emotional burden can be overwhelming at times.

My friends and I recently conducted a survey of the current House Officers practicing in Singapore, with 200 respondents. We asked these junior doctors how they felt about work, what were their stressors, and how work was impacting their well-being and mental health.

The most cited source of job dissatisfaction was working hours. We found that the median working hours for junior doctors was 12 hours a day, usually with an additional half day each weekend. Of those surveyed, 70% said that they had these working hours or worse. Add on the one or two calls (overnight duties on top of regular office-hour work), and we found that between 19% and 36% of junior doctors were working more than 80 hours a week. The hours don’t get much better – our senior clinicians pour in long hours to make sure patients are well cared for too.

Hours alone don’t make the profession tough; after all, many others outside of medicine work equally or even longer days. The expectations placed on doctors, and the emotional weight that comes from failing to meet those expectations is a different story. Someone once told me: “When you’re taking exams, the passing grade is 50%. But when you’re treating patients, your passing grade has to be 100%. Your patients and their families expect you to not make errors.”

The stress of having to keep up with those perceived expectations can erode a soul. We all want to give our best to our patients, but it isn’t always possible. More often than not, we find ourselves juggling a busy team list, responding to requests for instantaneous updates from family members, trying to cope with the idiosyncrasies of senior clinicians, and filling in the endless paperwork that seems to come with residency and being a doctor. I can’t even begin to count the number of times I’ve woken up in the middle of the night with palpitations because I thought I had missed out on something important for my patients.

What then when we fail and patients die? Watching someone you’ve cared for every single day choke to death on their last pained breaths – that scars you. You watch the family members around the now lifeless body, choking down tears amidst howls of grief. You can only say “I’m sorry about what has happened” as your mind races to figure out where you went wrong.

“Someone once told me: “When you’re taking exams, the passing grade is 50%. But when you’re treating patients, your passing grade has to be 100%. Your patients and their families expect you to not make errors.”

And then an uneasy guilt sets in. The guilt of wondering if the finger will be pointed at you if the witch-hunt begins, as has happened to doctors before you. We like to think that we are professionals who are above this, but it happens and happens too often. I remember a Facebook post from one of my batch-mates that sums this up well: “We can die, patients cannot die”.

It is no wonder then that so many doctors suffer from significant emotional backlash. In the same survey, we found that 47.5% of respondents scored above the cut-off point on a depression screening tool known as the PHQ-2: 18% were at risk of developing major depressive disorder (that’s THREE TIMES the national prevalence rate), with 67% showing significant symptoms of burnout.

I’m not telling you all this to scare you away from being a doctor. For all the difficulties, being a doctor brings with it a unique joy that you’d be hard pressed to find elsewhere. I’m sharing this because I believe it is important we confront and understand the challenges, to diagnose the issues that plagues doctors, and to find preventive mechanisms as a community and as individuals.

If I may be so bold, I’d like to share with you three things I tell myself, to cope with the difficulties of being a new doctor.

1. Be more than just a doctor.

When we spend so much of our lives in the hospital or with our patients, it can be easy to forget that being a doctor is just one aspect of who we are. While that identity is important to many of us, we need to actively remind ourselves that being a doctor is not our only identity. Being able to keep some distance from your job means that you are less likely to feel like your life is over when something inevitably goes wrong in your practice. You need to have a life outside of medicine too. Go out and enjoy your hobbies, spend time with your family, and discover life outside the hospital. You need to understand more than medicine in order to empathise with the myriad of patients who come to you for healing.

2. Know yourself.

While it is important to ask yourself what kind of specialist or generalist you want to be, it is more pertinent to know who you are as a person. Take time to ask yourself what your character flaws as well as strengths are, and what makes you different from those around you. You may find that those are just two sides of the same coin.

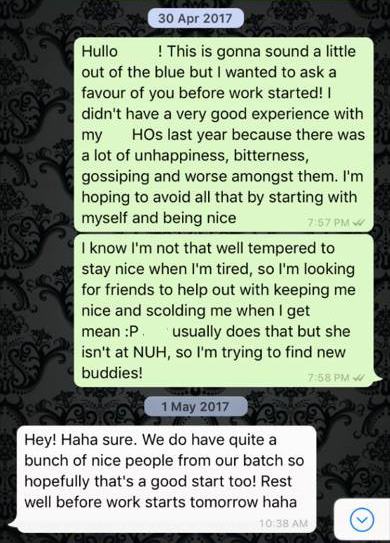

This understanding is important because it helps you figure out what kind of doctor you are, and helps you set realistic expectations for what kind of clinician you strive to be. For example, I know I’m not exactly the brainiest around and embracing that has helped me put away the anxiety of not being on the Dean’s list or having a thousand research publications to my name. Instead, I know I wear my emotions on my sleeves and that’s something I use to heal my patients. It helps me identify role models, and because of that I’ve been able to better utilise my emotions to connect with patients. As the months pass, I find myself holding on to the hands of wailing old ladies and comforting them after they hear that they have cancer or that they may never walk again. Knowing where I excel helps me build on it and gather professional satisfaction. Knowing yourself also means recognising your flaws. Wearing my heart on my sleeve also means that I showcase my anger and unhappiness in more spectacular fashion. The recognition of this flaw has helped me find mechanisms to reduce those instances and grow as a human being. The day before I started life as a House Officer, I sent out a text to a trusted friend to help me with this:

She still scolds me when I’m less than professional. While it may be a bitter pill to swallow when it happens, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

3. Love Fast, Forgive Easily

Working with other doctors with their own flaws and quirks in a high stress environment means that there will be times where you get angry with them. Throw in the general competitiveness of getting into a specialty and the baseline egotistical nature of doctors, and it is not hard to imagine that things can get ugly very quickly. I’ve seen more senior clinicians hold very public grudges against each other than I would have liked.

Even as junior doctors, we argue and fight. When others put you in a tight spot, it is easy to assume the worst of them. I remember being incredibly annoyed with a fellow HO when they left me to set an intravenous plug for a patient for four nights in a row. Even with ultrasound guidance, the anaesthetists couldn’t get the plug in, and there I was every night trying to set a plug. In that moment, it was easy for my mind to assume that my fellow HO was being lazy. While it was tempting to assume the worst of him and form a grudge, I found that forgiveness went far further even when it was difficult to. We eventually talked it out and he apologised for missing it out. He helped me a tonne when I was struggling later in the posting.

When we spend so much of our lives in the hospital or with our patients, it can be easy to forget that being a doctor is just one aspect of who we are. While that identity is important to many of us, we need to actively remind ourselves that being a doctor is not our only identity.

You’d also be surprised how much your colleagues care for and love you. I’ve been going through a really rough patch the past two weeks. I had delirious patients swearing at me at the top of their lungs whenever I walked past. I had been disappointing my boss each morning round. One of the patients I had been caring for in the past two months had died. And perhaps most importantly, my personal life was a mess. I was completely burnt out from work, often sitting in front of the computer in the office and not being able to move because of all the weight on my mind. I couldn’t eat or sleep for days, and I was withdrawing from the other HOs and doing excessive amounts of work to keep myself distracted. While they were my batch-mates, I didn’t feel like we knew each other well enough for them to care or for me to share what I was going through. Against all my expectations, they reached out to me and showed me a great deal of love and understanding when I was being difficult. They are the reason why I was able to drag myself out of bed and come and talk to you today.

There’s enough stress and unhappiness without us having to fight and compete against each other. So love fast, and forgive easily; you’ll find it returns to you a thousandfold when you need it the most.

All the best with the rest of medical school, and I look forward to seeing you in the wards.

From a presentation delivered to NUS Medicine students on 24 February 2018 at the NUS Medical Society Career Fair.