It Won’t Kill You to Talk About It

“Be careful then, and be gentle about death.

For it is hard to die, it is difficult to go through the door, even when it opens.”

D H Lawrence, All Souls’ Day

Those of us working in Palliative Medicine do not receive gifts from appreciative patients or their families. After all, the patients and families we serve may be grappling with weighty issues like dying and death. So it’s always a surprise to receive a note of gratitude from a bereaved family, and over the years, at least a quarter of the Thank Yous have been about conversations.

For example:

“Appreciate very much the conversation that we had when my daddy was first referred for palliative care. Thank you for asking the hard but much needed questions, and also for clearing the doubts that I had.”

“Thank you for eloquently touching on those end-of-life

issues, which had allowed us to come to terms with the situation despite the rapid course of the disease.”

The importance of having “The Talk”

Surely all of us, as we approach the end of our lives, would want treatment that is aligned to our goals and preferences. But how would our families and medical teams know what we want if we had never talked properly about it? Studies indicate that such conversations hardly happen, or happen very late, and tend to revolve around procedures and treatments, rather than personal values.

It is ironic that many of us put more thought and energy into planning a holiday, than we do in planning for our old age. As the saying goes, if you fail to plan, you plan to fail. Neither is the talk just about making a will, or what kind of funeral you want, although those topics do crop up. If I had to summarise, it would be about what matters to you, now and in the future, especially towards the end of your life.

Why is it so hard to talk about it?

Illness, dying and death have long been considered taboo topics across many societies. Just think how many euphemisms we have for the word “died” – kicked the bucket, pushing up daisies, or as some say in the Netherlands “hung up his clogs”.

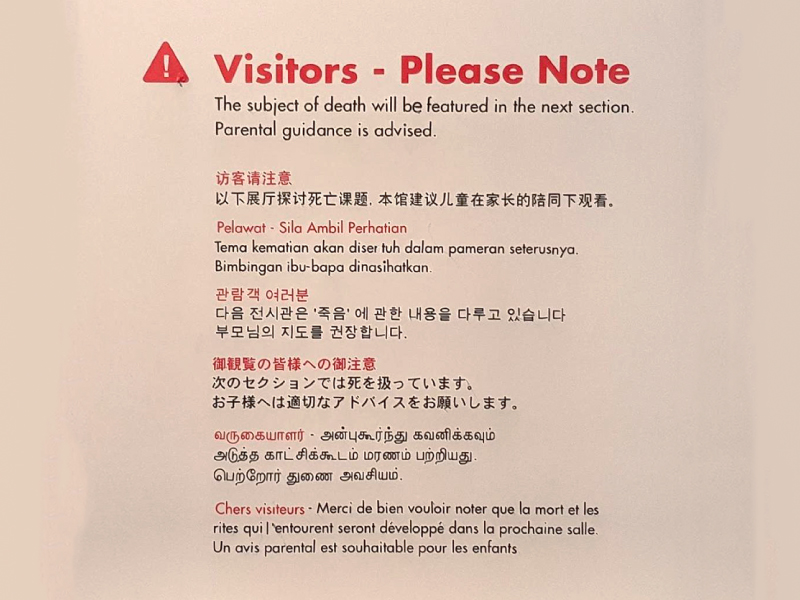

At the Peranakan Museum in Armenian Street, a display on funeral rituals merits a Parental Guidance advisory!

(below)

Jokes aside, it is a difficult topic, as it forces us to confront our fears, and brings up memories, regrets, emotions and anxieties. Healthcare professionals are as human as anyone else, and since there is little or no training available, it is perhaps no surprise that they might avoid the issue altogether.

Yet all of us will die one day, so this is relevant to everyone

and important enough that the whole of society should “own” the issue, rather than just leave it to particular groups like healthcare professionals.

How to start “The Talk”

The Singapore Hospice Council recently devoted an entire issue of its newsletter Hospice Link (available in English and Chinese) to the theme “The Power of Conversation”, sharing how discussions can be held gently and sensitively for old and young. I myself have had “The Talk” with adolescents, and with parents of very ill children.

Atul Gawande, in his bestseller book “Being Mortal”, recounts how he had to have this tough conversation with his own father who had been diagnosed with cancer. He used a 7-point tool called the Serious Illness Conversation Guide which had been developed by Dr Susan Block

and others as part of a comprehensive care approach for selected patient groups, called the Serious Illness Care Program by Ariadne Labs. In parts of the US, efforts are under way to ramp up training, as reported in Doctors Learn To Talk To Patients About Dying (Kaiser Health News).

My version, which I call “The Talk”, follows a similar outline. It has four broad categories:

• What do you understand about your illness and what does it mean for you?

• What is important to you – what do you want,what would you like to avoid?

• If your condition were to deteriorate in the future, what would be important to

you then, e.g. where would you want to be, who would you want to be with?

• Who would speak for you if you could not speak for yourself?

This has been further adapted at the National University Hospital into a conversation tool which we call the GAP (or Goals And Preferences) chat.

“Pearls on a string”

Although I may call it “The Talk”, it is in reality more likely a series of talks that we have with one another. As healthcare teams journey with their patients and manage their illness, we should also be gaining an understanding of who the persons are who live with these illnesses and how they want to live their lives.

Outside of healthcare, we can talk with our family or friends, in almost any kind of setting. In some countries, they have Death Cafes which provide coffee, cake and a safe space to talk. And so, like pearls on a string, we thread these conversations, making a necklace that grows and changes as we ourselves grow and change.

Seriously, it won’t kill you to talk about it. You might feel uncomfortable or emotional, but the elephant in the room will not go away just because you ignore it. Ironically, in talking about death and dying, you may discover a deeper understanding about yourself, and gain precious insights on how to LIVE.

A man asked my friend Jaime Cohen: “What is the human being’s funniest characteristic?”Cohen said: “Our contradictoriness. We are in such a hurry to grow up, and then we long for our lost childhood. We make ourselves ill earning money, and then spend all our money on getting well again. We think so much about the future that we neglect the present, and thus experience neither the present nor the future. We live as if we were never going to die, and die as if we have never lived.”

By Paulo Coelho – Like the River Flows