Feeling History’s Pulse

VETERAN CARDIOLOGIST HELPED

MAKE MEDICAL HISTORY

From an eyewitness’s perspective on the race riots of 1965 to pioneering and participating in groundbreaking medical innovations that included helping to save the life of Singapore’s first President, cardiologist Dr Low Lip Ping has some interesting stories to tell.

It all began when the Class of 1965 alumnus’ interest in the study of medicine was stoked by his father’s own passion for the subject.

In the 1920s, the senior Low had won a scholarship to the then – King Edward VII College of Medicine.

However, plans changed when Dr Low’s grandfather shuttered his provision shop, and his father had to forgo medical studies to work at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) as a pharmacy dispenser to support his family. Although he did not say it, Dr Low’s father had hoped that his son would succeed where he could not and become a doctor.

Dr Low’s family had moved into the staff quarters at SGH, and the young Lip Ping grew up in the hospital grounds, interacting with the staff there.

When Low junior graduated from Raffles Institution, he did well enough to enter medical school as a sophomore, or “super freshies” as they were nicknamed, under a special scheme at that time.

Medical school in the 1960s was quite different from medical school today.

“Teaching methods were quite straightforward. For anatomy – we had cadavers, at that time, there was no shortage of cadavers, so we could do our anatomical dissection on real dead bodies. In my middle years, I became acquainted with bacteriology and parasitology reports as there were a lot more parasites and bacteria including worms, amoeba, malaria, tuberculosis, torula, cholera, typhoid etc.then,” Dr Low said.

In his final year, Dr Low passed his examinations with flying colours. He topped his cohort and was awarded a medal on convocation day.

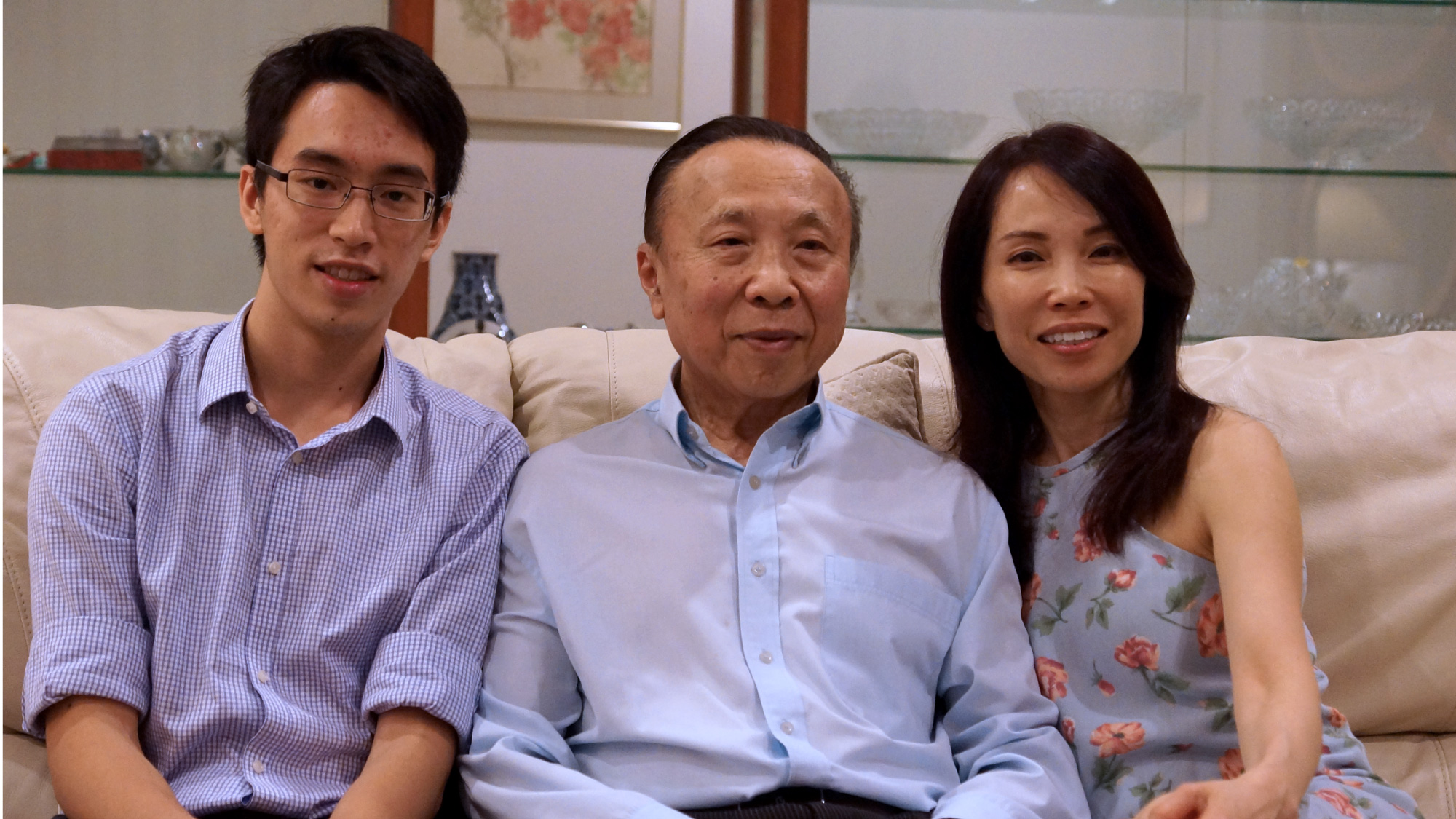

Dr Low Lip Ping, his family physician daughter Dr Lynn Low and his grandson Jason Tong, who is a Phase III medical student at NUS Medicine.

A moment to remember

After graduation in May 1965, Dr Low worked as a houseman at SGH’s Department of Surgery Unit B, then the Department of Paediatrics (East Wing), followed by one year as a medical officer in the University Department of Clinical Medicine (Medical Unit II) before he switched to specialise in cardiology, starting as a Research Fellow in the same department under the guidance of Dr Charles Toh and the late Professor Khoo Oon Teik, before becoming a Lecturer, Senior Lecturer and eventually Associate Professor in the University of Singapore’s Department of Medicine.

Singapore was then enduring a period of intense turmoil.

“At that time, there were racial riots, and I remember we were quite tense in the hospital, because we were told we might see people coming in injured. But amongst the students, there wasn’t any kind of resentment against ethnic groups. In fact, we had quite a big percentage of Malaysians, at least 30 or 40 per cent, including Malays from Malaya – because it was a period of transition when the University of Singapore was University of Malaya in Singapore when I first enrolled,” he said.

Dr Low was also working on the night Singapore separated from Malaysia.

“That evening, I was assigned to the theatre, and we took a break from surgery. We were sitting in the doctor’s lounge room, and then the television came on. It was that scene – when our first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew teared.”

Helping to make medical history

In the 1960s, the population suffered from infections, poor housing and overcrowding, bad nutrition, as well as a lack of clean water.

Shortly after, in the 1970s, there was a change in cardiovascular disease patterns among the population that prompted SGH to establish its first coronary care unit to help patients with heart attacks and investigate the causes of coronary heart disease.

“When I was a student, it was quite common to get rheumatic fever, a condition that follows an infection of the throat by a bacteria called beta-haemolytic streptococcal infection, and then subsequently you would develop an immune reaction. Part of the immune reaction would affect the joints, but sometimes, and more seriously, it would affect the heart valves. Patients ended up with rheumatic heart valve disease,” Dr Low said.

“And then things changed due to our economic status. We started to see more and more coronary heart disease. At that time, we didn’t know the significance of risk factors like blood cholesterol, blood pressure, diabetes, smoking and obesity, which caused a lot of cardiovascular disease, apart from rheumatic heart disease, and in particular coronary heart disease. We began to see more and more people coming to hospital, dying of heart attacks and so on, so it was decided that maybe that was one area to look at.”

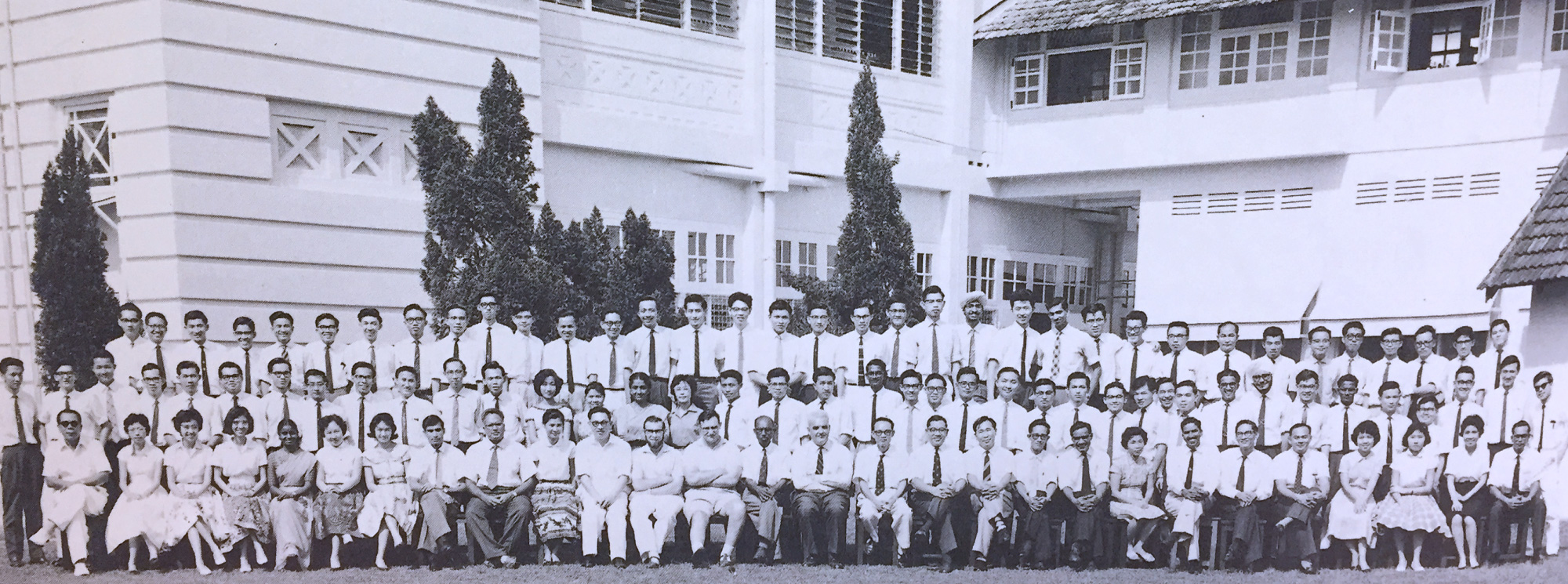

A young Dr Low Lip Ping (back row, ninth from the right) in medical school in 1961.

When Dr Low went to study in Duke University in 1972 for a year, he, as well as other local doctors, learnt how to do coronary angiograms, echograms for the first time. These doctors returned home and started offering diagnosis and treatment using these techniques in the late 1970s.

And this was only the start of many more cutting edge procedures and medical knowhow in the field of coronary care in Singapore.

Dr Low was part of the first medical team to insert a catheter and a pace maker for a patient in Singapore.

“Nobody had actually put in a catheter to do temporary cardiac pacing or implanted cardiac pace maker. But I saw these patients all needing it because some would come into the hospital with very slow heartbeats, and if don’t help them, then eventually they would collapse and die. So I went to the library and I took a book that described cardiac pacing by one of the pioneers in the UK, London. I read it from cover to cover three times, and went to source for pacing catheters that we could use for cardiac pacing,” he said.

His team managed to seek funding from the Osaka Rotary Club through the Singapore National Heart Association for the equipment, and they prepared for the first patient who needed cardiac pacing.

In 1968, a patient with a very slow heart rate and had to be resuscitated every now and then, was transferred from the Toa Payoh Hospital to SGH. Dr Low inserted a temporary pacing wire, which could not be taken out unless she had a permanent pacemaker implanted After raising funds for the permanent pace maker, and reading up on the medical procedure, Dr Low placed a pace maker in the same patient, together with his team. The first pace maker lasted 11 months, and he subsequently performed two more procedures and kept the patient alive for another six years.

“Unfortunately after five to six years the patient died, not because of a heart problem, but a stroke,” he said.

In the early 1970s, defibrillators were scarce, and there was no optimum method of performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

SGH’s coronary care unit owned a defibrillator, which Dr Low put to good use when a patient suffered a cardiac arrest in the hospital. This patient then became Singapore’s first patient to be successfully defibrillated from the procedure.

And having a President for a patient

During his stint as a fellow in SGH’s coronary care unit, he also had the honour of defibrillating Singapore’s first president Yusof Ishak not once, but twice. President Ishak went to Australia and developed atrial flutter-fibrillation while he was there. He then saw a cardiologist in Melbourne who told him to return to Singapore for medical treatment, as it was too heavy a burden to bear if anything happened to Singapore’s head of state while he was in Australia

“I asked them (President Ishak’s physicians) what would happen if something adverse were to happen while he did the electrical cardioversion, and they said, “Then you would have to leave the service.” But I did it on him (President Ishak) and his heart went back to normal rhythm,” Dr Low recalled. He defibrillated President Ishak within five minutes, and the procedure was successful.

“Well it was a stressful moment, but I wouldn’t say it was the toughest because I had done other patients with similar problems,” he added. Dr Low performed the same procedure a second time for President Ishak a year before he passed on.

In 1980, Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre was just established and they were looking for doctors to start private practice in its premises. Dr Low left SGH to venture into private practice, where he has remained to this day. It’s a career that sports a most resounding coda – his daughter and 21-year-old grandson are following in his footsteps: she is a family physician who graduated from NUS Medicine and he a Phase III student at NUS Medicine.