From Swords to Ploughshares

FROM SWORDS TO PLOUGHSHARES

The Afghanistan that much of the world pictures is that of a struggling country in a constant state of emergency: a land of dusty village houses, hostile, bearded men in turbans, fields of opium poppies, and all the while, a raging insurgency. Convinced that his medical knowledge should be the means to help alleviate suffering, Dr Wee Teck Young left his medical practice here in 2002 to join an NGO that was looking after Afghan refugees in Quetta, Pakistan. The experience showed him an Afghanistan that news reports failed to present – a land where people endure lives of hardship, sometimes with stoic humour, amidst the daily threat of violence and death. These days, medical practice takes a back seat as he serves with the NGO that he helped set up. It aims to help Afghans regain their dignity and find peace and restoration through various social enterprises.

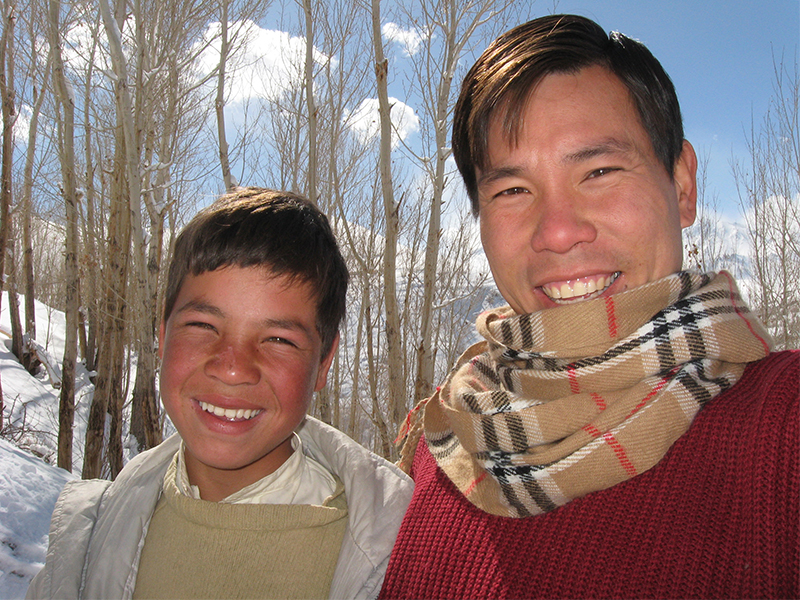

Home for the year-end holidays, Dr Wee (above) marvels at the frowning concentration of fellow train and bus passengers as they scroll and swipe their way through digital pages on their personal devices.

The NUS alumnus (MBBS Class of 1993) who in 2005 started and still works with the award-winning NGO, Afghan Peace Volunteers (APV) in Kabul, finds the fixation with mobile phones disturbing because it obstructs real human-to-human conversations – and relationships are best built and forged when there is actual interpersonal interaction. Relationships, he reasons, cannot be possible when people are cocooned in their own digital worlds, their real lives uninhabited and disintermediated by technology.

“There’s something in Singapore that I noticed over the years. In the MRT, besides people staring at their smartphones – which is a global phenomenon now – we have this idea that the phone makes my life more fulfilling and meaningful. How did we get to this, how did we believe that machines that we manufacture could do that, getting stuck in their phones in the MRT, not talking to one another, even at meal times in restaurants?”

Technology alienates and de-humanises

It is a totally different experience in Afghanistan, he says, because life is unfettered and uncluttered. The conspicuous consumption and pursuit of material wealth is absent over there because the focus of most Afghans is – to put it plainly – staying alive and finding the means to get back on their feet again. Here, “there’s too much of everything… we think we can go on living this way and not suffer its consequences, we think that if the consequences come to us because we eat and buy, we can solve it,” he says, eyes furrowed in exasperation and bewilderment.

War cannot usher in the peace

The 13 years that he has lived in Afghanistan, where he had planned to use his medical skills to serve locals there as part of an international public health NGO, made him acutely aware of the desperate conditions that the Afghan people endured, the poverty, illiteracy and daily violence that was just a bomb away. His journey and transformation from medical volunteer to peace advocate and self-sustaining social entrepreneurial champion is well-documented in numerous articles and news reports, including one in The Straits Times in July last year.

All recount how the doctor from Singapore travelled to a war-ravaged land to become a mentor to the Afghan Peace Volunteers, an inter-ethnic group of young Afghans dedicated to building non-violent alternatives to war. Kindness, mutual respect and recognition, courtesy – these are the fundamental ingredients to building lasting relationships; they are the key to resolving conflict, says Dr Wee, 48 and a fluent speaker of Dari, one of two main Afghan languages. He is also conversant in Pashtun, the other lingua franca.

Think of all the blood and treasure that the US and NATO have expended in trying to bring the insurgency to heel, or the attempts to destroy the opium trade. “The general approach of international governments is to wage war. Most recently, NATO’s head said we’re going to increase the war on drugs. There’s more drugs now than when we first started off. And the same applies to Mexico, Columbia, and many other things. There’s a global drug commission, it’s a body made up of five ex-presidents mainly from the South American countries.

“And for the past 10 years they have issued reports to say that the war on drugs has failed, we need to shift our method. These are not moral statements, these are statements of science that it doesn’t work, it’s not effective, so let’s try to change the approach.” What Dr Wee has in mind is a deliberate emphasis on nonviolence in the work and programmes of the Afghan Peace Volunteers. It is a repudiation of the seemingly endless cycle of violence and the grinding insurgent warfare that has gone on in the country since US troops invaded Afghanistan in the aftermath of the 2001 September 11 attacks in New York City.

Instead of guns, try saffron

“If these huge apparatus and machineries would think a little, question, then they would follow the path of many NGOs, in replacing opium with saffron (in encouraging people to explore agriculture to make a living). We have such great technologies nowadays, right?” It is the path that is being advocated by the Afghan Peace Volunteers and it harkens back to a recurring theme that Dr Wee, who was given the Afghan moniker, Hakim (meaning “doctor”), hammers away at throughout our conversation. He is convinced about the APV way to helping Afghan people be self-sufficient economically, with agriculture a possible lifeline for growth, and growth leading to self-sufficiency, pride and dignity.

“There is a story I can tell with regard to relationships: this was when I was working as a medical officer in a hospital in Singapore. I think it was close to midnight that I finally got some time to go see a patient in his room who was in his last days. He wanted to tell me something, which he indicated through a piece of paper and a pen. In those few moments he wrote a message for me – and I regret not having kept that piece of paper. The message was about relationships.

“He wrote, ‘I have enough wealth to last me a lifetime, and that of my next two generations. Yet all that is not very meaningful now. Please, please, please don’t, don’t pursue money; pursue relationships.” The note continued, “You will not regret another hour earning another $1,000; you will regret that you didn’t spend more time with your families or your friends.”

Transformational relationships

“Relationships with people have changed my life, have changed the group, and I believe can change the whole world,” Dr Wee says. One relationship that he has not embarked upon thus far however, doesn’t bother him. “I don’t plan to be single. I didn’t plan for either marriage or singlehood. I think if it comes, it comes, if it doesn’t… it doesn’t”.

It is the AFV that has got his wholehearted attention. “Our doors are open to any Afghan, both male and female, who is interested in joining the activities that promote nonviolence. We also have been deliberate in including the most vulnerable segments of Afghan society, the women who are illiterate, the impoverished, and the street kids. We want to continue to allow any person who wants to engage in the practice of non-violence, to be a member of the Afghan Peace Volunteers.”

It is a cause that this NUS Medicine alumnus is determined to serve till the every end. “I think I’ll do it as long as I’m alive. The circumstances may change, and my specific role and job even may change but I am passionately for this journey towards relationships. I feel that I am a relational being and I want to live my very, very short life in relationship with as many people as I can. I don’t have to be close to all of them, it’s not physically possible, but each person has got great value.”