Issue 40 / November 2021

Ethically Speaking

Trustworthy Governance for Sharing Health

Related Data

ike many major health economies, Singapore is investing in precision medicine and health research.1 Precision medicine is an emerging approach aimed at optimising health outcomes with information from various sources to better tailor medicine and healthcare.2 Those sources include genome sequencing data that is linked with electronic health records and other lifestyle and environmental information.

Many large health datasets, including those used for precision medicine, use an opt-in model of broad consent for de-identified data to be shared with researchers and third parties. With broad consent, the research goals and future potential research uses are described to participants in broad strokes rather than in specific details. Programmes use broad rather than specific consent due to the impossibility of predicting, in advance, all the specific research projects the data might be accessed for in future. Data is typically de-identified and data security processes are used to protect the data during storage and when shared.

Health data research sharing raises several ethical issues, partly because of inherent trade-offs between competing ethical values. For example, while autonomy and privacy are important, these may sometimes be overridden. In the absence of specific consent, people responsible for governing health data must make decisions about how and when to share data in a way that respects public expectations in balancing the ethical trade-offs. The concept of a social licence refers to a privilege that is implicitly granted by society to an organisation or profession to operate, often in the absence of specific consent. Where there is social licence for an activity, people are willing to accept the activity as morally and socially permissible. However, public trust is eroded whenever the licence is breached, which negatively impacts future health data sharing initiatives.

Thus, it is important to understand what activities and data sharing arrangements are socially and morally acceptable for trustworthy data governance.

A mixed methods study

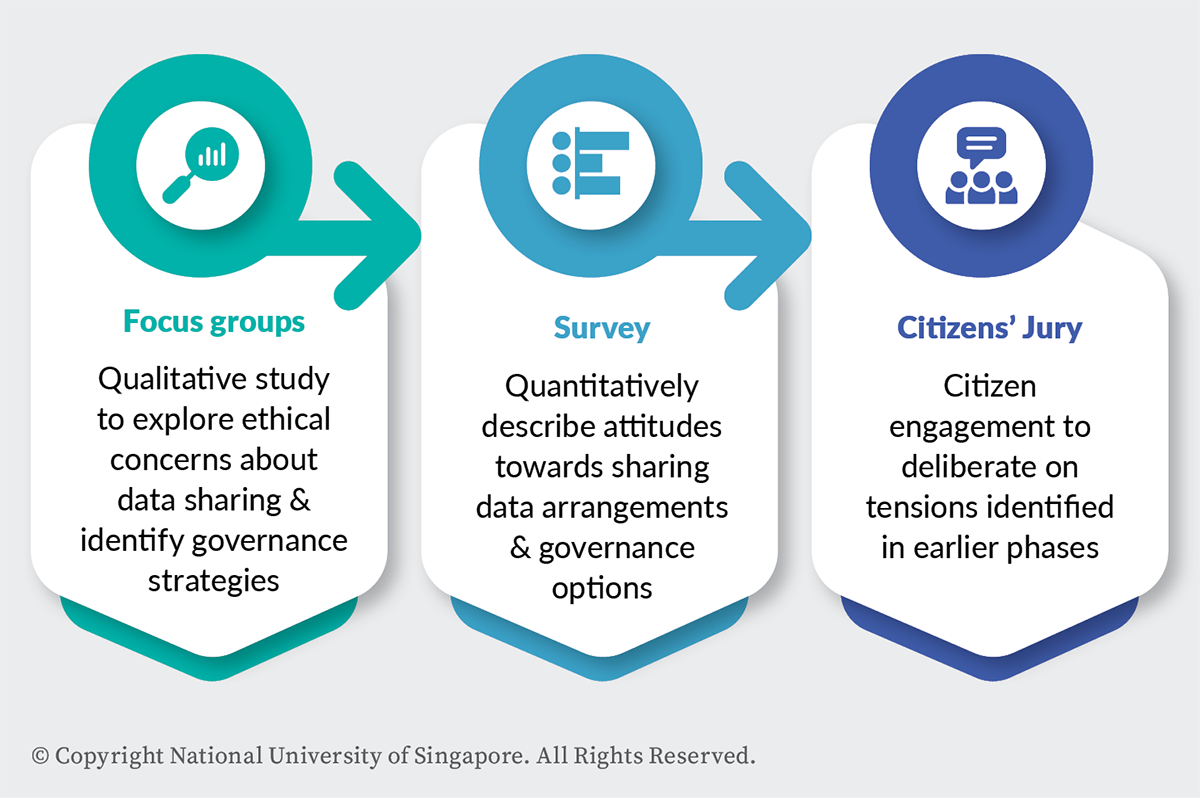

To address these issues, we conducted mixed methods research to examine the ethical trade-offs and make recommendations for designers of health data governance systems in Singapore. Our research provides important insights on the ethical views Singaporeans have about sharing health-related data for large-scale initiatives like precision medicine, and what trustworthy data governance might look like in this context. As summarised in Figure 1, the research was conducted over three phases:

Figure 1. Mixed methods tri-phase design

Phase 1. Focus groups

In 2019, we conducted seven focus groups with 62 participants in Singapore in three languages (English, Mandarin and Malay). The focus groups aimed to find out the ethical concerns Singaporeans have about data for precision medicine research and identify suggestions for governance strategies.

Phase 2. Survey

In 2020, we conducted a national survey of 1,000 Singapore residents in three languages (English, Mandarin and Malay). The survey measured public priorities and preferences for sharing health-related data. The survey was an adaptive choice-based conjoint analysis (ACBC)3-4 with four key values identified in the focus groups: uses, users, data sensitivity and consent.

Phase 3. Citizens’ Jury

In 2020 and 2021, we convened a four-day Citizens’ Jury with 19 Singaporeans. The Citizens’ Jury is a deliberative method for engaging the public in complex policymaking processes.5-7 This group of people should be diverse and inclusive of the community, although they do not aim to be ‘representative’ of the population. As jurors spend several days talking to experts and relevant stakeholders, and deliberating on the issues with one another, they can generate more informed recommendations than survey respondents or even focus group participants. A Citizens’ Jury is therefore useful because it allows non-experts to become familiar with a complex topic and offer informed policy advice. The aim of our Citizens’ Jury was to ask an informed group of Singaporeans to deliberate on the question:

Under what circumstances, if any, is it permissible for a national precision medicine programme to share data with private industry for research and development?

We developed this question for the Jury to consider with guidance from an advisory panel representing key stakeholders in the implementation of precision medicine in Singapore.

Key findings

The key findings from our qualitative focus groups suggest there would be conditional support for precision medicine research that shared genomic sequence data and information contained within electronic medical records, with university researchers and healthcare institutions. Support was conditional on the perceived social value of the research and appropriate de-identification and data security processes.

The discussions demonstrated relatively sophisticated understanding of the inherent risks of storing and sharing large linked datasets, and analysis of the trade-offs between possible harm and potential benefits of a hypothetical precision medicine programme. Compared to prior research reported overseas, our focus group participants projected an international outlook and similar attitudes towards the potential benefits of precision medicine. Although it was also suggested that an independent oversight body may help to strengthen public trust of data sharing arrangements for precision medicine research, that is governed under broad consent regimes.

Participants in the focus groups all expressed high levels of trust in government to ensure data security and privacy protections, despite several large-scale breaches having occurred in recent years, as in the cases involving SingHealth and the HIV Registry. This finding was consistent with outcomes of our national survey where government agencies and public institutions were the most trusted users of health-related data for research (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mean trust score for institutions using de-identified health data for IRB-approved research. A score of 6 represents “trust totally” and 1 represents “distrust totally”. The whiskers indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Most, but not all, of the survey respondents (64%) indicated that they would be willing to share de-identified health data for research that has approval from an Institutional Review Board (IRB) without needing to re-consent for each study (Figure 3). For the ACBC analysis, the most important values in respondents’ decision-making were the user of the data (39.5%) and the reasons why they were using it (28.5%). The least important values were the sensitivity of the data (19.5%), and what type of consent was obtained (12.6%). Most respondents indicated that it would acceptable for government agencies and hospitals to use de-identified data for health research with broad consent; more so than sharing with universities and pharmaceutical companies. Sharing health data with private insurance companies for any purpose, was unacceptable, even with specific consent.

Reasons for unwillingness to share

de-identified data include:

|

• |

215 (60%) reported that they want to have control at all times even if this means being asked for consent many times. |

|

• |

125 (35%) reported that they don’t trust the research processes and protections. |

|

• |

86 (24%) reported that there are potentially more risks than benefits. |

|

• |

12 (3%) reported other reasons. |

Reasons for willingness to share

de-identified data include:

|

• |

430 (67%) reported that the potential benefits of health research are greater than the potential risks. |

|

• |

348 (55%) reported that they trust the research processes and protections. |

|

• |

123 (19%) reported that it would be too troublesome to consent to every single research project. |

|

• |

10 (2%) reported other reasons. |

Figure 3. Willingness to share de-identified data for Institutional Review Board approved health research without needing consent for each study.

Finally, in response to the question we asked the Citizens’ Jury, they concluded that sharing data with private industry would be permissible under some circumstances. Those circumstances were set out in recommendations that were made with three prevailing assumptions:

|

1. |

Data shared with private companies should be de-identified. |

|

2. |

Users to be required to opt in to precision medicine and have the right to withdraw at any point. |

|

3. |

When people consent to the precision medicine programme, information should be comprehensible. |

While the Jury was generally open to sharing precision medicine data with pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, and technology companies, there was much resistance towards sharing with private insurance companies in the current regulatory environment.

Implications for trusted health data governance in Singapore

Across the three studies, four values emerged as key considerations for ethical and trusted health data governance in Singapore: public interest, fairness, accountability and transparency.

The core justification for data sharing was public interest. Participants in both our focus groups and Citizens’ Jury offered examples of public benefits: more accurate and beneficial medical care, fewer adverse events, cheaper medicines, extended longevity and better quality of life, improved understanding of the health of Asian populations, treatments for rare diseases, strengthening of Singapore’s research and development sector and job creation. Some suggested health and genomic data were “public resources” and should only be shared for the public good. Sharing data from a public resource with private companies solely for their commercial benefit would not be acceptable. Profiteering may be acceptable when there is corresponding public benefit for Singapore.

Focus groups and Citizens’ Jury participants expressed persistent concerns about social justice, particularly on perceived rising health and financial inequality in Singapore, the cost of healthcare, and potential genetic discrimination and/or stigmatisation. The benefits of precision medicine should be fairly accessible to those in need.

While study participants recognised the potential benefits of sharing data for precision medicine outweighed the potential harm; they were cognisant of various risks including data breaches, misdiagnosis, and group harm such as stigmatisation, discrimination, and loss of access to medical care. Accountability for data breaches and misuse are essential to mitigate these risks. Punishment should include criminal charges proportional to the offence, be punitive, and apply to individuals, teams and organisations, both local and overseas. Transparency would be crucial for demonstrating trustworthiness in data governance, to allow the various members of the public with stakes in precision medicine to assess the benefits and risks of data sharing for themselves, and decide whether the trade-offs are worth it.

Finally, an interesting finding was the de-emphasis of consent. Existing literature on public attitudes to health data sharing assumes consent is the decisive and over-riding ethical issue,8 and prior research suggests that individuals often prefer specific consent.9 However, consent was the least important concern in our survey and none of the Citizens’ Jury’s recommendations focused on consent. This finding suggests that resource intensive consent options (such as specific and dynamic consent) may not influence Singaporeans’ decisions to support data sharing or participate in precision medicine.

This research is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Social Science Research Council Thematic Grant (MOE2017-SSRTG-028), the National Research Foundation Singapore and the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council.

-

Garrido P, Aldaz A, Vera R, Calleja MA, de Alava E, Martin M, Matias-Guiu X, Palacios J. Proposal for the creation of a national strategy for precision medicine in cancer: a position statement of SEOM, SEAP, and SEFH. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(4):443-447. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1740-0.

-

Wang ZG, Zhang L, Zhao WJ. Definition and application of precision medicine. Chin J Traumatol. 2016;19(5):249-250. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.04.005.

-

Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, Johnson FR, Mauskopf J: Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health—a Checklist: A Report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value Health 2011, 14:403-413.

-

Almario CV, Keller MS, Chen M, Lasch K, Ursos L, Shklovskaya J, Melmed GY, Spiegel BMR: Optimizing Selection of Biologics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Development of an Online Patient Decision Aid Using Conjoint Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2018, 113:58-71.

-

Street J, Duszynski K, Krawczyk S, Braunack-Mayer A. The use of citizens’ juries in health policy decision-making: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2014 May; 109:1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.005.

-

Smith G, Wales C. 2000. Citizens’ juries and deliberative democracy. Political Studies 48: 51-65.

-

Bloor, M. & Wood, F. (2006). Citizens’ jury. In Bloor, M., & Wood, F. Keywords in qualitative methods (pp. 31-32). London: SAGE.

-

Fiore RN, Goodman KW. Precision medicine ethics: selected issues and developments in next-generation sequencing, clinical oncology, and ethics. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28(1):83-7.

-

Garrison NA, Sathe NA, Antommaria AH, Holm IA, Sanderson SC, Smith ME, McPheeters ML, Clayton EW: A systematic literature review of individu- als’ perspectives on broad consent and data sharing in the United States. Genet Med 2016, 18:663-671.