Should Medicine Go “All In” on Ageing?

By Professor Brian Kennedy,

Director, Centre for Healthy Ageing,

National University Health System (NUHS)

Perceptions of ageing are changing radically. In historic times, when an elder was a rarity, the tradition was often to show great respect and rely on the wisdom and experience that someone who lived through many challenges acquired.

In the 20th century, however, the advent of many healthcare and societal changes led to a dramatic decline in age-extrinsic causes of mortality. The number of elders (that is those over 65) in the population has grown dramatically.

Today, even centenarians are not a rarity. In fact, they are among the fastest growing segments of the Singapore population. Yet, modern societies, whether Eastern- or Western-based, have turned toward a youth revolution, and elders are not consulted as much as in the past. With as much as 30% of the population over the age of 65 in the near future, it is time for societies to re-evaluate ageing and the aged. How will

Singapore, a progressive-minded country, find ways to keep elders healthy and empowered to contribute?

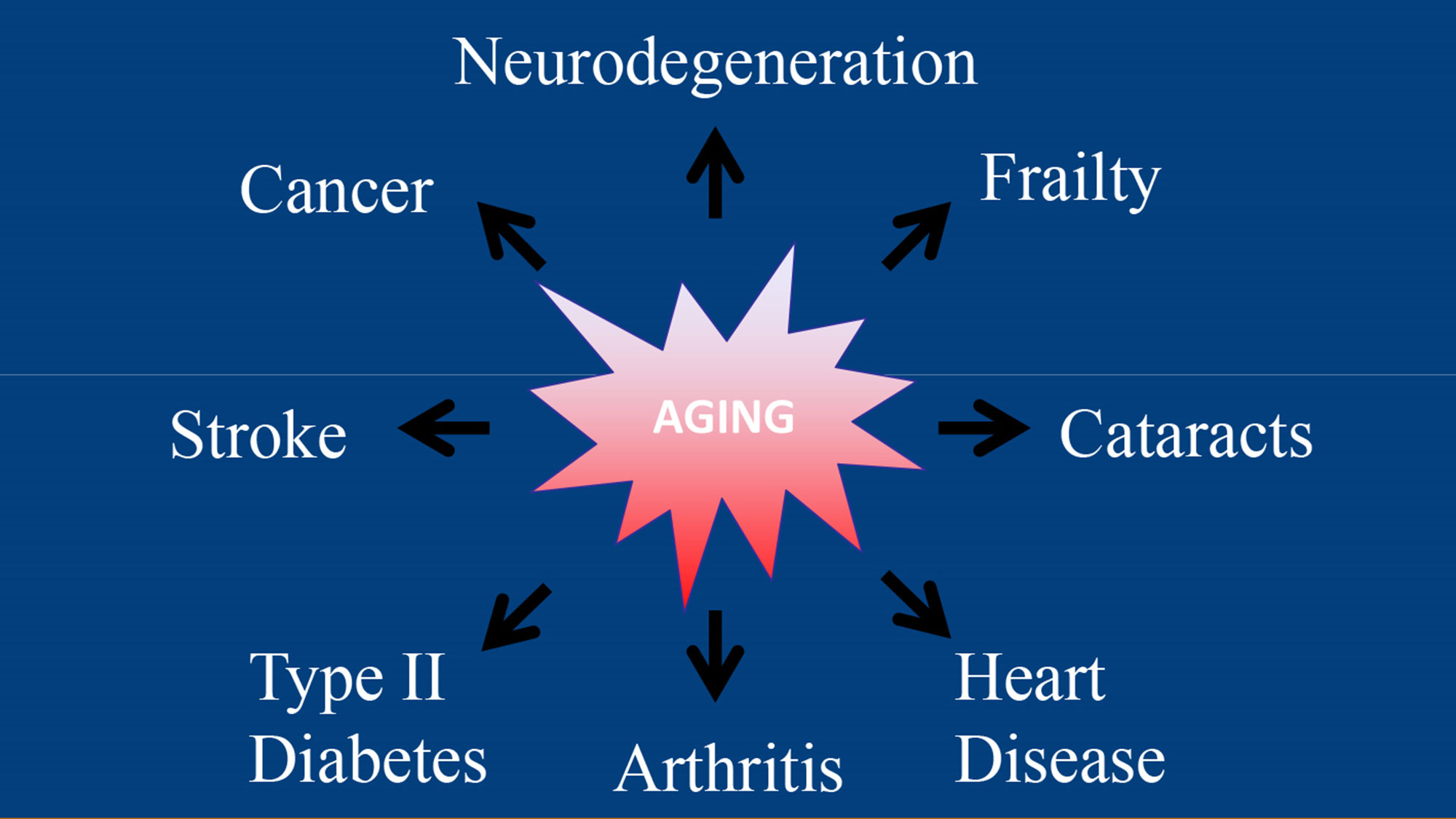

In medicine, ageing is also treated differently, or put more directly, mostly ignored. This stems from a perception that ageing is unalterable. Everybody ages and nothing is to be done. Compare that to someone who diagnosed with cancer. Say “cancer”, and doctors pull out all the stops. If successful, a person is said to “beat cancer.” Rather, if a largely healthy older person says that they are trying to live longer, they are attempting to “cheat ageing.” By way of another illustration, there are more oncologists than gerontologists in Singapore, even though cancer rates are way below ageing rates.

Nothing illustrates the point better than the Framingham risk score, which predicts the likelihood of coronary heart disease. Points are assessed (or taken away) based on a number of variables, with higher points indicating more risk.

Most of us know that high cholesterol is a major player. Take the example of a 44-year-old unhealthy woman. She has moderately high cholesterol (200-239mg/dL; +6 points), smokes (+7 points), low HDL (<40mg/dL; +2 points), and has high untreated systolic blood pressure of (>160mm Hg; +4 points). That is a total of 19 points, giving her an 8% chance of being diagnosed with coronary heart disease in 10 years.

Compare her score to that of a relatively healthy 75-year-old woman, who has relatively normal total cholesterol levels (160-199mg/dL; +1 point), doesn’t smoke (0 points), has normal HDL (50-59mg/dL), and has untreated systolic blood pressure between 130 and 139 mm Hg (+2 points). It looks great, but she gets +16 points based on her age alone, for a total of +19 and an identical 10 year risk. Physicians would mobilise with the younger woman, recommending lifestyle interventions and pharmacologic interventions. With the older woman, they would say she is doing ok, with perhaps minor recommendations about diet and exercise.

It is now possible to extend not only lifespan in animals, but also healthspan, the disease-free and functional period of life.

Why ignore the biggest risk factor for CHD (age) and treat the lesser ones? One could argue that the older woman has lived her life and the younger one has many years left, although this is really ageism. Everyone should get best of care. A second argument

brings us back to the beginning – ageing is not alterable. But all evidence points otherwise. In animal models, ageing researchers have found a range of strategies to slow ageing, from lifestyle interventions to supplements to drugs, and limited studies in humans suggest that some of these interventions will translate well. Put simply, it is now possible to extend not only lifespan in animals, but also healthspan, the disease-free and functional period of life. The time has come to test this strategy in humans, since successful extension of healthspan will have extensive economic benefits in Singapore and dramatically improve life quality with age.

The National University Health System recently established the Centre for Healthy Ageing to develop a multi-faceted approach to ageing in Singapore. It will oversee clinical trials with interventions hypothesised to slow ageing, validating their efficacy and ensuring safety. The Centre will perform research to redefine state-of-the-art geriatric care for elders, promoting the prevention of age-related decline and managing life quality after the onset of morbidity. It will also promote education in healthy ageing and, as part of this goal, look for more reports in coming months about the interventions linked to longevity and what it means for our life choices today.

Ageing is arguably the biggest medical challenge of the first half of the 21st century and with resources and effort, the challenge can be successfully met in Singapore. Imagine a goal of being “healthy at 100.” It may sound a bit far-fetched, but it could be possible for most people alive today. With a fallback strategic outcome of “not bad at 90,” it seems clear that we should be “all in” when it comes to healthy ageing.