Patients, Palliative Care and Lessons the Textbooks Don’t Teach

PROJECT HAPPY APPLES

Patients, Palliative Care and Lessons the Textbooks Don’t Teach

Head & Senior Consultant, Division of Palliative Care,

National University Cancer Institute, Singapore (NCIS)

When I was an undergraduate, there was a running joke that medical school was good at producing muggers. Nothing to do with robbery of course, “mugging” is colloquialism for rote learning, which Singaporean students are all too familiar with. Since then, styles of teaching and learning have evolved and it is no longer necessary – or even useful – to memorise reams of facts, especially when knowledge is changing so quickly and information is readily available at the touch of a button. What doctors need to know nowadays is how to access information and to be able to analyse, prioritise and navigate their way through complex situations and systems.

A few years ago, the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine undertook a comprehensive curriculum review for this very purpose of preparing graduates for the 21st century – streamlining, cross-referencing and curating, in order to provide flexibility and opportunities for students to learn according to their needs. But a considerable of learning is known to occur outside the formal curriculum, and contributes to the way undergraduates grow up and into their future professional selves.

That’s an Interesting Name…

Project Happy Apples or PHA started small, with two medical students who were then volunteering at Brightvision Hospital, and who came up with the idea of selling apples to raise funds for hospice patients. As the project was handed down to successive generations of students, more activities were added, and refinements made.

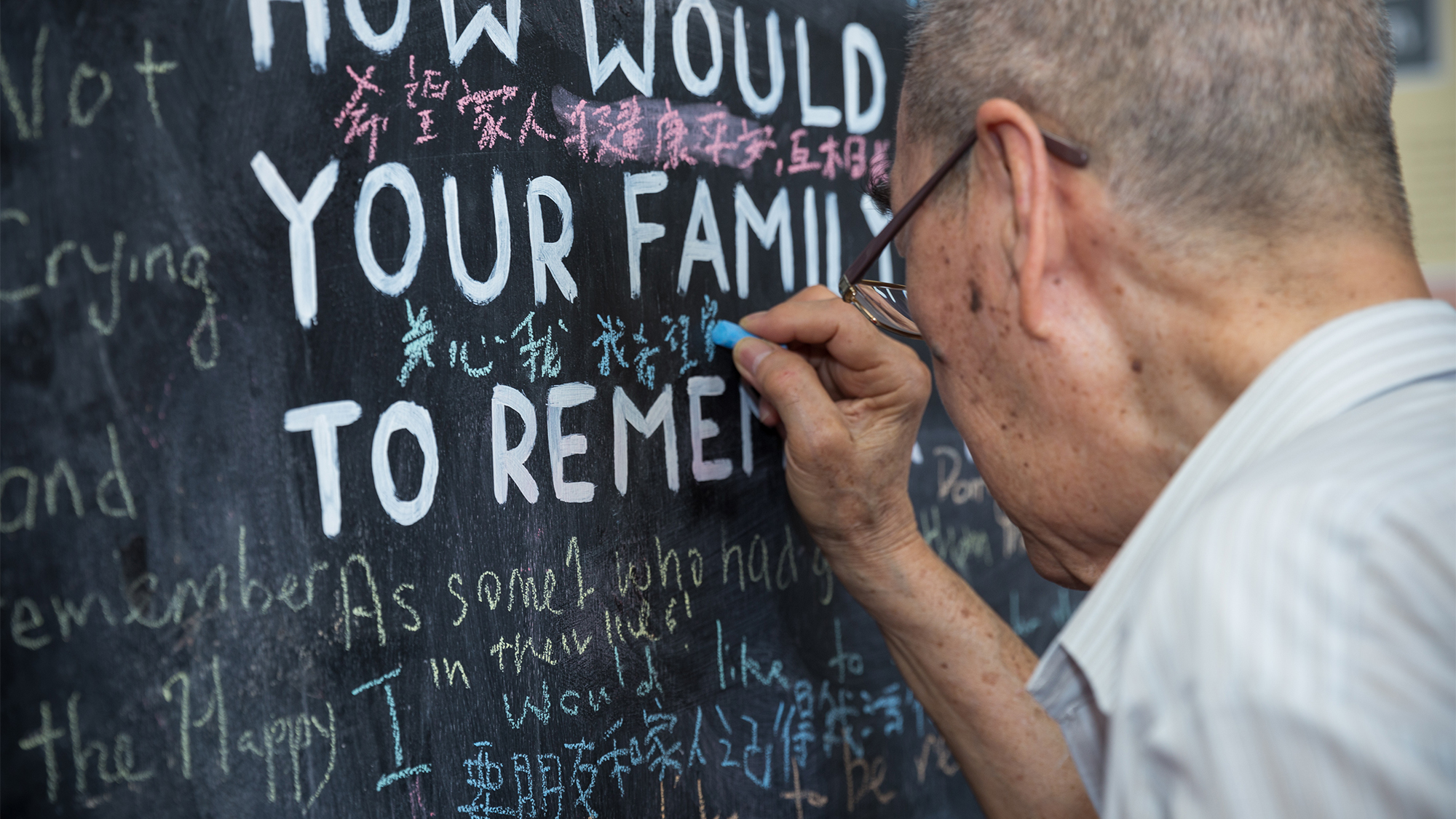

Currently PHA volunteers run various activities: befriending of patients; encouraging people to consider their end-of-life preferences through activities like “Before I Die” and a simulated “Telephone Booth” (to “call” your younger self); raising awareness of palliative care through patient stories and public exhibitions.

So what do students get out of PHA?

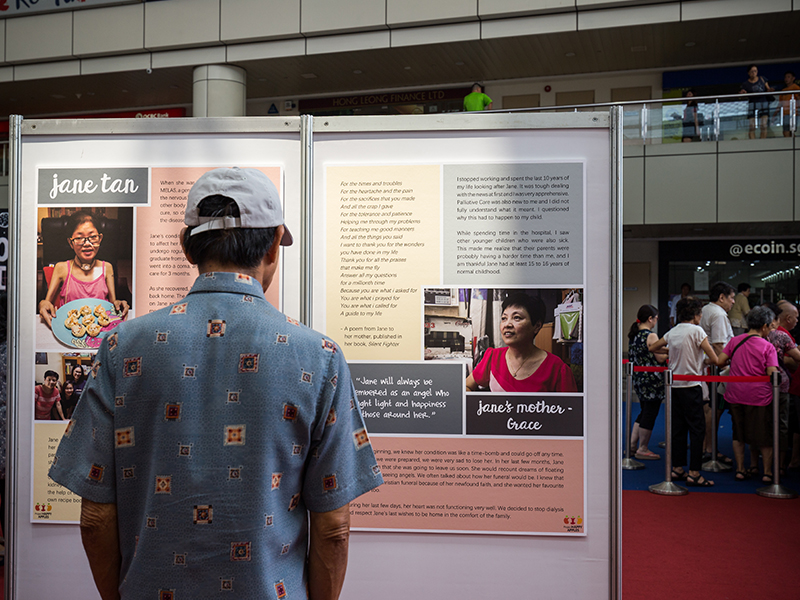

In October 2017, PHA ran a major public event at Toa Payoh Hub called Life Stories Exhibition which was attended not only by the PHA co-founders (who are now

residents), but also by previous years’ student volunteers. One can only surmise that PHA means something significant to them. The PHA volunteers are mostly in their second year at medical school, which means they would not have had formal teaching in Palliative care. Many of them come into the project full of curiosity, hoping to learn about Palliative care and how to interact with patients, but I would argue they come away with rather more. But don’t take my word for it, here are the some of the students’ impressions:

Zowie Khoo – Head of Volunteer Management

It has been a fulfilling journey with Project Happy Apples, though not without its ups and downs. But there’s not a thing I would change about the past year. Although my assigned role in the core committee was volunteer management, I’m thankful that I got the opportunity to do and experience much more.

One of my greatest worries was not being able to gather enough volunteers for the Life Stories Exhibition. Luckily, the response was good and we managed to have a capable bunch of volunteers to help us. Despite lacking background knowledge, they were able to pick up fast. Something that I realised was that the awareness of palliative care amongst the younger generation is still pretty low as it was their first time hearing about palliative care – even among medical students. It was a heartening experience to have my committee members and volunteers come together to serve a common cause of reaching out to the community to raise awareness about palliative care. Talking about palliative care not only requires knowledge but also sensitivity and a caring heart.

It was a novel experience for me to interact with people from different walks of life. The life stories that were shared inspired me to fight harder for my dream and to serve the community wholeheartedly. Besides that, it highlighted the importance of spreading the understanding of palliative care to allow the community know that there are many resources that they can turn to.

Philip Ong – Head of Research & Initiatives

We started the year full of energy, ready to make so many changes to our befriending programme, to ensure that our volunteers have the most enriching and memorable experience. However, our seniors quickly redirected us and patiently worked with us to refine our ideas. It was only later that we realised, in our eagerness to beef up the programme, we’d missed the big picture – there was beauty in the simple befriending experience.

As I headed on to the clinical years, I realised that this same thread holds true – it was so easy to be caught up in our many plans when talking to patients: learning more about the presentation of a disease, understanding the associated complications, or doing a physical examination. But, there were times when the patient just needed a listening ear, to share about something that was bothering them, and PHA has made me more aware and willing to explore these concerns with them, armed with the belief that a simple but heartfelt conversation can mean so much to them.

Benedix Sim – Head of Public Outreach

“Medicine is both an art and a science” – a commonly touted phrase within our field. But more often than not, a much greater emphasis is placed upon the scientific rigor of the subject and many of us get lost at sea, with our minds focused on finding a cure or diagnosing a disease. But as the saying goes “to cure sometimes, treat often but to comfort always.”

Working with patients undergoing palliative care was an eye-opener to say the least. Not every patient was like Morrie in Tuesdays with Morrie. Each had their own values and particularities. It was challenging at first, learning to adapt to each individual and discovering that there was never a one-size-fits-all approach that was described in our texts to help us. We often found ourselves at a loss, wanting to value-add and attempting to emulate a good doctor and to contribute to that patient. But more often than not, some company, a good listening ear and a kind word from time to time is all that our patients need.

Through organising Project Happy Apples, we aspire to bring forward the messages and stories that we learnt from these patients and to advocate for the public to learn to live life to the fullest. Life is short, and should never be taken for granted. We also hope that all our juniors going through the programme will reflect upon their values that guide them as future healthcare professionals, so as to develop better skills in providing holistic care for their patients and to finally understand what we mean when we say that “Medicine is both an art and a science.”

Tay Kuang Teck – Head of Volunteer Training

It was truly a blessing to be a part of Project Happy Apples – a platform to grow as a person, understand myself better, and develop new skills. I can still remember how motivated I was to make a positive change to the project at the beginning of the year. Back then, I thought I was clear about what I wanted to do for the project. Soon after, I began to realise how little I knew about befriending, the project and more importantly, about palliative care.

I learnt the most from the patient I befriended this year. Initially, I came in with the mindset of trying to do my best for the patient. Gradually, I began appreciating the meaning of befriending, which is about the rapport and friendship between us, enjoying each other’s company. It was a great privilege to be a part of her journey, understanding the patient behind the disease. I will remind myself not to be fixated on managing the illness only, but also do my best to promote the well-being of the patient.

My befriending experience had also been a source of motivation for me when I was helping with the running of public outreach events. I became more open-minded to new perspectives and learning opportunities. Every interaction with the public became an opportunity to understand them better and offer differing perspectives about end-of-life care. Ultimately, everyone is unique and we should not educate others on how to live life. We are there to provide a supportive platform for them to consider how they want to live their lives to the fullest.

The Project Happy Apples team (from left to right) Zowie Khoo, Benedix Sim, Tay Kuang Teck and Philip Ong