Cross-Causeway Collaboration Raises Cure Rate for Childhood Leukemia

By Dr Khor Ing Wei,

Dean’s Office

“Cooperation is the thorough conviction that nobody can get there unless everybody gets there.”

– Virginia Burden

On the face of it, childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) appears to have been licked, with cure rates of between 80 and 90 per cent. However, the challenge remains to improve outcomes for the small proportion of patients who do not respond well to standard treatment for ALL and have very poor outcomes.

In 2002, four hospitals in Singapore and Malaysia pooled their paediatric patients with ALL, totaling more than 500, with the goal of solving this problem. This group of patients formed the basis of the seminal Malaysia-Singapore ALL 2003 (MS2003) study, which was a game changer in the treatment of ALL. Published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2012, the study showed that ALL patients could be classified into different groups by their risk of severity, and the intensity of their treatment tuned according to the risk level. The patients were classified using clinical characteristics, genetic mutations, and a marker called minimal residual disease (MRD), which is a measure of the proportion of cancer cells still remaining after treatment. This more accurate approach led to just as high a cure rate as for standard treatment, but with fewer side effects overall.

Another important finding from the 2003 study was that patients with a change (a deletion) in a gene called IKZF1 had a worse prognosis than those lacking the deletion. The IKZF1 gene produces the IKAROS protein, which is needed for B cells (the immune cells in our body that produce antibodies) to mature. However, the 2003 study did not consider IKZF1 deletion status when classifying patients for treatment.

Following up on this highly successful study, the team started a new study in 2009 (MS2010) that also evaluated children from one to 18 years old with newly diagnosed ALL. This time round, the researchers specifically enrolled children with B-ALL, a type of ALL that affects mainly B cells.

The MS2010 study, published in the 10 September 2018 issue of the Journal of Clinical Oncology, stratified the children with B-ALL similar to the earlier study, and also took into consideration whether they had the IKZF gene deletion. If a patient had this gene deletion, they were classified as “high risk,” even if they lacked conventional risk factors.

After classifying the patients, the researchers treated the high-risk group with more intensive therapy than the standard-risk and intermediate-risk groups. This mainly involved giving two blocks of an intensive three-drug regimen (fludarabine, cytarabine and daunorubicin) in the second phase of treatment, at around one month and two months after start of treatment. In addition, for two years, the researchers also gave a drug called imatinib (Gleevec®) to patients in the high-risk group who had the BCR-ABL1 gene abnormality, which is common in ALL. The team then followed the patients in the study for nine years until January 2017 to evaluate how well they did.

To assess whether the new treatment strategy was more effective than the one used in 2003 (which did not take into account the IKZF1 gene deletion), the research team looked at two main measures in B-ALL patients with the IKZF1 deletion and compared them between the MS2010 and MS2003 studies. Compared with MS2003, the new treatment approach in MS2010 reduced the five-year risk of relapse (risk of cancer recurring within five years after a period of remission) by half (from 30 to 14 per cent) and improved the five-year overall survival by one third (from 70 to 92 per cent) in this patient group. Patients who had the IKZF1 deletion but lacked the BCR-ABL1 abnormality saw their five-year risk of relapse cut down by half. Although the effect was even more dramatic in patients who had the IKZF1 deletion and were also BCR-ABL1 positive, this could have been due to the imatinib treatment.

This study, which is the first to use the IKZF1 gene deletion to determine treatment in children with ALL, was possible only because of the strong collaboration between researchers in Singapore and Malaysia. By each contributing their unique strengths and patient bases, they were able to discover a more effective treatment approach for an especially severe subset of high-risk ALL patients.

As Associate Professor Allen Yeoh of the Department of Paediatrics, NUS Medicine and the first author of both papers, sees it, “It is wonderful that working very closely together between NUS and University of Malaya and four hospitals, we can pick and answer critical treatment questions for the children of the world. Putting together our scientific and clinical capabilities between Singapore and Malaysia, the Ma-Spore group continues to give our children with leukaemia the best chance of cure.”

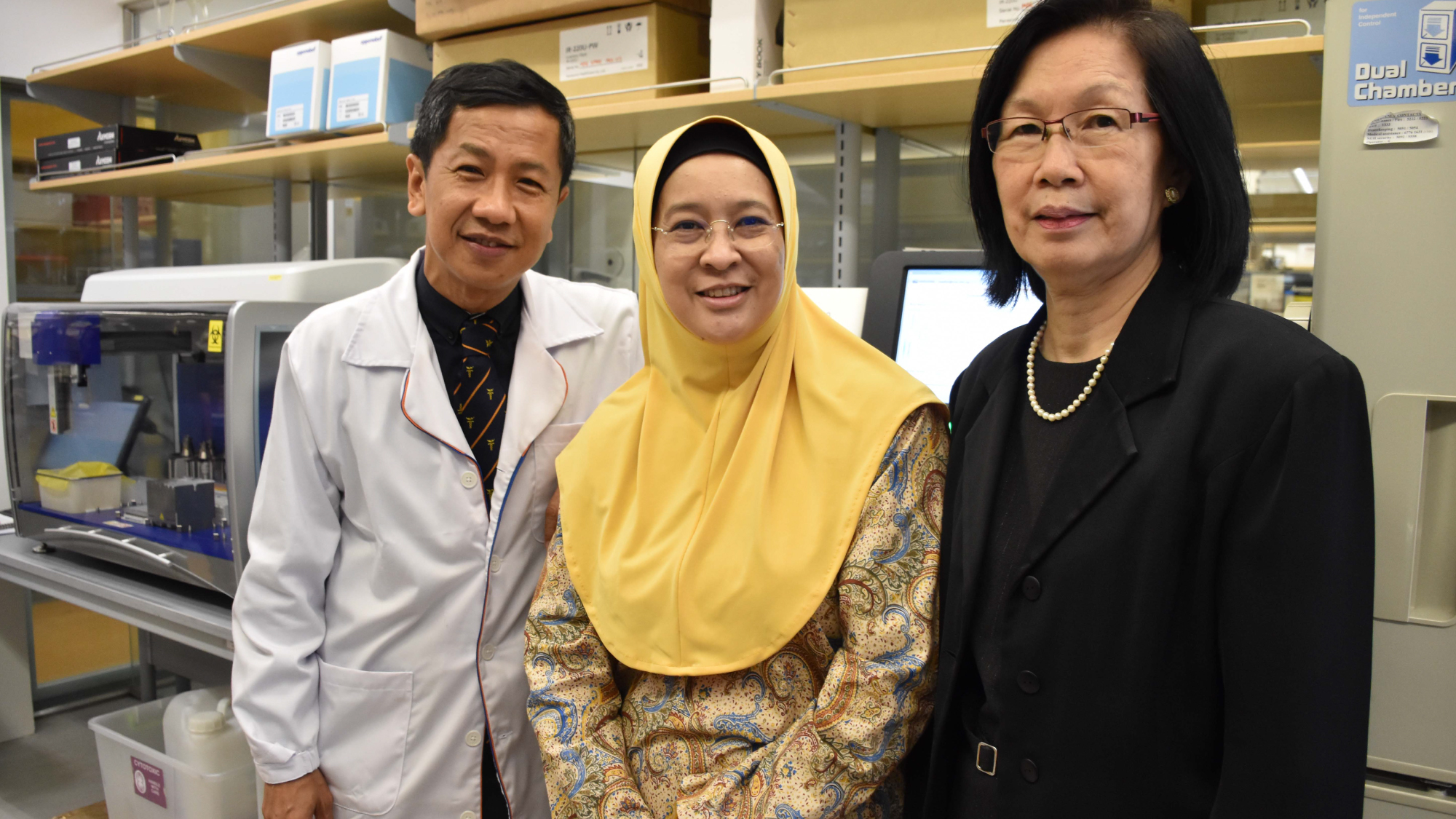

Associate Professor Allen Yeoh with his collaborators – Professor Hany Ariffin from the University of Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur,

and Associate Professor Tan Ah Moy from KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.