Not By My Hand Alone – A Surgeon’s Journey

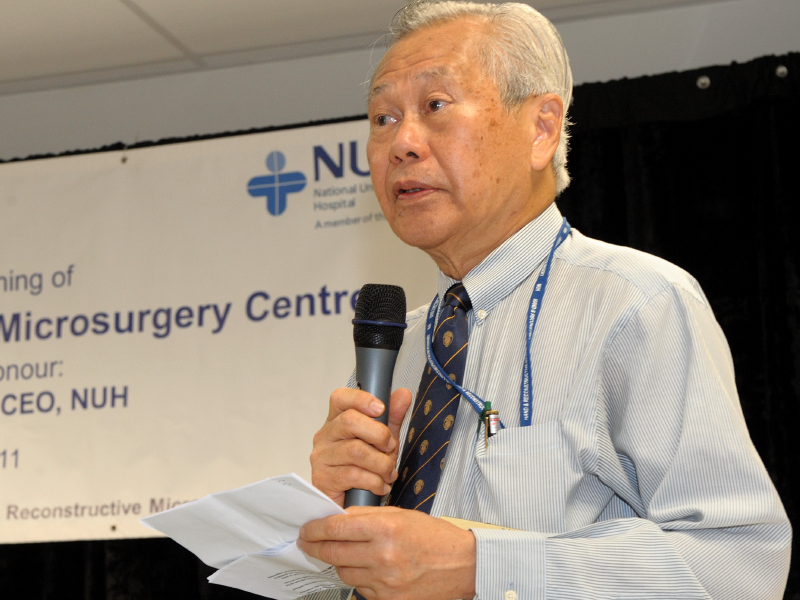

So-so medical student, struggling houseman, long-suffering orthopaedic and hand microsurgery training and tribulation in the Temples of Doom, Sacrifice and Respite, and final redemption – NUHS Physician-in-Chief Professor Aymeric Lim (Class of 1990) shares about the ups and downs, ins and outs, highs and lows of his multi-faceted life.

Pain and pleasure come to us not as opposites but as twins, strangely joined . . . a massage after a long day in the garden . . . a log fire after a hike in a snowstorm. . . . Nearly all my memories of acute happiness involve some element of pain or struggle.

– Paul Brand, Pain: The Gift Nobody Wants

Walking in Paul Brand’s Shadow

Good morning. My aims today are three: one, to thank all the people who’ve helped me on this journey. Two, to share what a great job surgery is, and three, to show all young residents that it is possible to be an academic surgeon. It can be very tough though, but they have to hang in there. I feel very proud that I’m part of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, which has such a great heritage.

If there’s a role model I have – it’s Dr Paul Brand, the English orthopaedic surgeon who transformed the treatment of leprosy sufferers through his ground-breaking surgical work. If there’s a journey that I would have wanted to emulate – well, part of it would have to be that of Paul Brand’s.

The son of missionaries, he was sent back to the UK because his parents stayed in India. He later returned to India where he started his leprosy work.

Paul was once greatly touched when unable to speak the local language, he gave a leprosy patient a friendly touch to assure him he would help him as much as he could. Tears started to stream down the man’s face and Brand asked a colleague what he had done to distress him. She replied “You touched him and no one has done that for years. They are tears of joy.”

Brand wrote in his book “Pain: The Gift Nobody Wants”, “Previously I had thought of pain as a blemish of creation, God’s one great mistake. But pain stands out as an extraordinary feat of engineering valuable beyond measure.”

Pain is part of medicine. Pain is a necessary part of one’s career. And pain is part of one’s life. So this is not just a metaphor for disease, it is a metaphor for our lives, and it is also a metaphor for the work that we do, which centres a lot around the relieving of pain.

A second quote by Brand elaborates the role of pain. “Pain and pleasure come to us not as opposites but as twins, strangely joined”, and he gives some examples.1 I think most of us would agree in our careers that more often than not, the greatest joys come after long periods of pain or suffering.

I have always wanted to be a surgeon since I was nine. My journey began in medical school and my medical school record is quite stark. Three or four re-exams, three re-vivas. I think I only got two Cs – one was for O&G. and one was for Anatomy, and the rest was all Ds. So it wasn’t a brilliant career in medical school. I struggled. But I had good times too, thanks to my friends Jui Lim, Ivor Lim, and Chayan.

Lifelong friends: Dr Jui Lim and Dr Ivor Lim

National Service in the army was a good break and working hard there gave me some credit for when I applied for a traineeship.

The Wonder of Anatomy

Though medical school was a struggle, I want to mention one of the most inspiring teachers I’ve ever had, and that’s Professor Rajendran K. He taught me the wonder of Anatomy. In those days before digitalisation, we had two PowerPoint projectors. He would place layers and layers of anatomical drawings upon each other. That wonder – it wasn’t just the teaching of anatomy – it was the wonder of it which has stayed in my head for all my life.

The Key to Understanding Medicine

Another person who gave me the key to understanding medicine is Associate Professor Yeoh Khay Guan. He doesn’t like this story, but I’ll tell it. I was a very confused fourth year medical student, we were in Ward 58 and we were all struggling. Khay Guan probably was a H.O. (House Officer) and we were all grumbling. But he said “No, medicine is simple”. And we said “What do you mean it’s simple?” He said “Look, everything is either infection; inflammation; infarct; tumour etc” – and we all know this. So, I think it took me about a month to digest and a month to actually believe it. But once I had that key, it actually became a lot simpler and I was able to pass my final year exams without too many problems

Another person who exercised huge impact in medical school was Prof Bala. There was a patient who came in with a limp, and I couldn’t identify the gait. So he grabbed hold of my ear, and during this time, he was making this poor patient with an antalgic gait walk up and down. He tugged at my ear till my head was on the table, then someone whispered “antalgic”, I said “antalgic” and finally, he let go of my ear.

I think we should return to this kind of teaching. I mean, right now with students and residents writing whistle-blowing reports when they’re scolded in the ward, I think it’s time to reset things a little bit!

Orthopaedic Traineeship

I went on next to Orthopaedic traineeship. After completing a posting in Orthopaedics NUH, I was still holding my forceps in a certain way and got scolded by Chew Soo Ping. He said “How can you hold instrument like this?” I said “I’ve never been taught how to hold it”. He taught me how to hold the instruments properly.

Abu Rauf and the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons

Next came Part 1 in Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons. It was in the anatomy dissection hall and again, I was struggling.

There was a really mean Scottish examiner and basically, my ship was sinking. He was asking question after question on the abdomen, and I was going down. The other examiner was Prof Abu Rauff. He kind of stepped in and took over. He asked me what are the lobes of the liver and I also could not remember! So I said they are like – which is true – the cantonments of Paris. That is actually how they were named. That’s all I could remember. Anyway, he realised that there were problems. He said “What’s this?” and I said “That’s the gall bladder” and he said “Very good, boy”. We kind of delayed things – it was delaying tactics – until the bell rang and I passed my Part 1!

Microsurgery

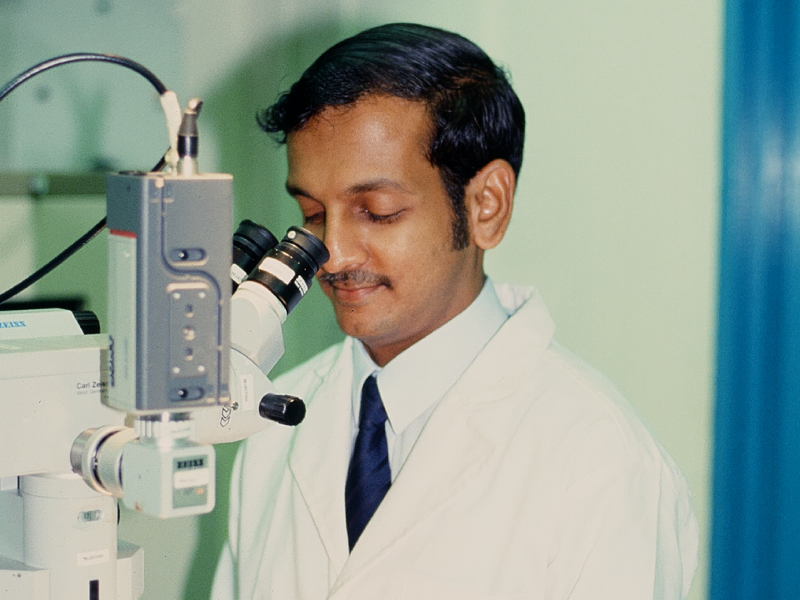

Then I was introduced to microsurgery. My first surgical procedure there was with Prof Kumar. We wheeled in the microscope and when I looked through it, there was a whole different world. I was completely fascinated. That’s where I decided – it was probably the most painful decision I ever took in my life – to try and join the Department of Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery.

People couldn’t understand why. My friend, Ivor Lim, was trying to get me in and I remember what Khong Kok Sun said: “Why you want to join that department?” I said “Because I want to do microsurgery. So, he said “Don’t worry, no one wants to join. In three years’ time, there’ll still be a position there”, because it was really tough.

So I asked to join the department.

The Three Professors – Pho, Satku, Kumar

Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery was a tough department for some wrong reasons and some right ones.

It was defined by the three professors – Prof Robert Pho, Prof Satku and Prof Kumar. It was a hard school. It was like going through the surgical version of the SAF’s Ranger course. I was doing 10 calls a month, and on the non-call days I often had to come back to help the senior registrar with microsurgery. That was really tough. There were many opportunities though. I think it is very important for young surgeons to do a lot of surgery. Because it’s just like golf or tennis – when you’re young, you play a lot, you’ll have the right strokes. I was taught how to do surgery by my professors.

The Awesome Threesome: (clockwise) Prof V. Prem Kumar, Prof Robert Pho, Prof Kandiah Satkunanantham.

Three Operating Theatres, Three Temples

So three professors, there were three operating theatres, and it felt like three temples. These were the Temple of Doom, the Temple of Sacrifice and the Temple of Respite.

The Temple of Doom – that was going to Prof Pho’s operating theatre. It’s hugely stressful. You go in, you scrub, and we all go and look – Prof Pho is analysing the case – but we go look at the x-ray box for about half an hour while Prof Pho thinks and discusses it. That’s what we used to call “praying to the x-ray god”. Then the surgery starts, and there was such an aura of mystique, it was almost mythical.

The second temple was the Temple of Sacrifice – that was Prof Satku’s O.T. And this was like a Mayan Inca temple. So often it was human sacrifice, and the human sacrifice was usually me. It felt like Groundhog Day, well, every week. That was the kind of recurring theme of my Orthopaedic training. But I must say, I did 50 T.K.R. (Total Knee Replacement) and I was taken through them by Prof Satku.

The third temple was the Temple of Respite. You know, Prof Kumar – he’s quite a fierce guy. So you can imagine going into his O.T. was considered a respite? But I remember that he taught me surgery and he taught me many things. One of the things he kept telling Prof Pho was – when Prof Pho was wondering how come I wasn’t doing any research, or not doing well or whatever – he kept telling Prof Pho “you can lead a horse to the water …” and all of you know the rest of the quote.

Major Surgical Influences: What They Taught Me

Prof Satku was a harsh disciplinarian. I think I needed it – not all of it – but I needed some. He taught me real respect for the patient, and healthy obsession for hygiene and the conditions around the surgery. There is one thing I always tell everybody, whenever we did the rounds, we would start in Ward 51, a subsidised patients’ ward. Prof Satku would treat his subsidised patients the same as his paying patients. I followed him closely for many years and I never, ever saw a difference. You know, just having a role model like that, just sets the tone for you for the rest of your life.

I’ll go next to Prof Kumar.

He was a fountain of goodness. He always said to give people the benefit of the doubt. With Prof Kumar, that was the joy of surgery and teaching. I remember one day in the OT many years later, he said “Aymeric, this is the best job in the world”. I asked him why, and he said he had just taught his registrar how to do a shoulder operation and he was just so happy about it. That was infectious, and that was very, very special. He taught me about shoulder surgery, which became very useful for brachial plexus surgery later.

Then there’s Prof Pho. I think without him and all his struggles getting a microscope in in the 70s – and I think that’s for the same reason, we should have a robot here. The robot of the 2000s is the microscope of the 70s. If he hadn’t struggled so hard, if he didn’t set us up at that level in the world, we would not be where we are. He’s the one who taught me how to use the knife – not as a knife, but as a brush.

I wouldn’t be where I am if it wasn’t for my teachers and mentors: Prof Pho let me have the scalpel, Prof Kumar would take us out for drinks at the Guild House, and Prof Satku actually fed me grange wine in the Tanglin Club. He also operated on both my knees! So the justice and mercy, it was tempered by that.

Then there was (Kour) Anam Kuah. He was a fantastic hand surgeon. And when he was teaching me how to stitch, he said “Every stitch should be your best stitch. Do you understand that?” And I said “Yeah, every stitch should be your best stitch”. “What does that mean?” I didn’t get it. Then he said, “It means that if every stitch is your best stitch, your best stitch becomes the norm”. That applies to everything in life. So in everything, do your best, and your best becomes your norm.

Another influential teacher was my mentor in France, Professor Michel Merle. He too has had a great influence on my career. Through his academic and surgical mentorship, I had many papers and also co-wrote two books with him, and edited two textbooks which are pretty good and have good diagrams, but are difficult to sell in Singapore!

I will now talk about leadership. A quote that aptly describes the values and qualities which I believe all leaders should possess is a verse from the Bible, Micah 6:8: “He has showed you, O man, what is good. And what does the Lord require of you? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.”

What are the elements there? To act justly – that also means rules and principles, and standards. To love mercy – that means you have to care for your people and your staff in what you are doing. And to walk humbly with your God – if you’re leading, you’re not leading for yourself, you are leading for a greater cause. If you have the opportunity to lead and if you have these three elements combined, it usually works.

The pain and suffering and joys when you are in leadership, they become more acute. I would say that you’ll always need 20% of people to stand in the gap for the rest of the population. I’m really happy to say that here at the NUH and NUHS, many of you are standing in the gap for our patients, our work, and our institution. So I’m very proud to be part of this.

Prof Aymeric Lim (left) with a patient in Afghanistan.

Missions

Another highlight of my professional life is going on medical missions. That’s where I feel I’m most alive. Last year I was in Cambodia and I was walking to the Angkor Hospital for Children, and I thought “God, this is what I was born to do”. There’s nothing that inspires me more than doing missions so I try and do two a year.

An exciting medical mission was the 2009 one to Afghanistan in Spin Boldak. We did some surgeries here, and this is me with one of the young soldiers in Afghanistan there at that time. And they said they were going to kill Western foreign aid workers, so I thought I would grow a beard. It worked, they said I looked like a Kazakh.

Another was with my close friend, Liew Shern-Ern who was in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery for some time in Zambia. There, your resources are minimal and you need to do a lot of new things with so much less.

To end, I have a profound sense of gratitude to all the people I’ve worked with and learned from. I have been very, very blessed to enjoy such a great career. This verse says it all: “Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.”

Thank you very much.