If I had to do it all over again – Reflections of a clinician-educator

Published online: 7 January, TAPS 2020, 5(1), 76-78

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-1/PV1083

C. Rajasoorya

Department of General Medicine, Sengkang General Hospital, SingHealth, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Reflections represent exploration and explanation of events and may reveal anxieties, errors and weaknesses; they do however have positive influences highlighting strengths and successes for better future outcomes. The author reflects on his practice as a clinician-educator close to four decades and shares a perspective of his retrospectively pleasant but arduous journey into medical education.

II. BAPTISM INTO CLINICAL TEACHING

I embarked on teaching medical students because I did not want them to encounter the same struggles I had with learning voluminous medical facts and lists. Moving into clinical years and with more experience, I understood the importance and applicability of basic sciences with greater clarity. As a way of guiding juniors and preparing for my own higher examinations, I got interested in teaching clinical medicine. Repeatedly ringing in me is what a clinical-skills foundation teacher profoundly reminded us that teaching is a way to expose our knowledge gaps and help us remember better. Being fortunate to have been taught by some of the doyens of medicine as well as having a high clinical load, it surprises me on how much I learnt from both my students and patients.

III. REJUVENATION AND EVOLUTION

Once, I had wrongly succumbed to the idea “the new generation is different and is less interested in learning”. Disillusioned, I almost contemplated giving up teaching. Fortunately, I closely worked with a few brilliant, enthusiastic and hardworking interns who rekindled my interest in teaching and awakened in me the need to customise teaching to the generation we are dealing with (not vice versa). A teacher must accept that his experience in the early years will not mirror those of his students, rather than reminisce the past. The new generation is learning and practising in a different era where patient expectations are different, knowledge has been democratised and voluminous knowledge can be easily accessed via the internet and smartphones. Clinical teachers may take benefit to emphasise on clinical application and reasoning rather than factual content.

When I had a family of my own, the similarities between teacher-student and parent-child stirred in me the importance of ownership, responsibility, and avoidance of the remark “no time to teach”. It also dawned on me the extent of pressure we inflict on our students and how it contributes to vanishment of the joy of learning. I learnt that learning can be intuitive, varied and supplanted by metaphors of daily activities of life and knowledge application.

For a long time in my career, I used to go on an ordered line of questioning whenever I dealt with clinical groups. There was predictability who was going to be asked next. I learnt subsequently such an order of questioning stops the thinking process in all except the one in the “hot seat”; the rest passively “switched-off”. I have now adopted a routine (albeit, struggled) to get to know my students by name and ask questions in a random order which allows everyone to think; besides making them feel appreciated being called by their name.

I have found it useful to open difficult questions to the entire group – letting the student know it is a difficult question and providing a challenge to the brilliant to attempt it. At times I have openly admitted that I did not know the answer to that question at their age (or even later!). This resonates very well with students who feel teachers understand their difficulties. The dictum that no question is ever a stupid question cannot be overemphasised.

An experienced teacher can sense which student is struggling and distract attention quickly to another party so that the embarrassment to the individual struggling student is removed. It is important to recognise a student with the knowledge but hesitant to answer; cajoling the answer out of him is an art that comes with experience. Where a wrong answer is provided, it would be useful to ask for the reasoning rather than brush it aside with an emphatic “no”. A couple of years ago, I asked one of my rather always quiet students why she volunteered to be in the “hot seat” for a short clinical case – her answer of not being intimidated by me and having confidence that I would not embarrass her was a powerful lesson on how fear kills enthusiasm. I was fascinated to hear in later times that she had expressed a desire to be a clinical teacher!

Experienced teachers will be bold enough to admit they do not know. Admittedly, this was never easy for me during the growing years, until recent times. An occasional bright spark student may know the answer and he or she should be given credit for educating the teacher. Mutual respect promotes learning for all involved. Time and again, I had experienced and learnt from my colleagues (particularly from my overseas stints) of how protecting ego and hiding ignorance serves only to retard the process of learning. Eating humble pie may seem daunting and embarrassing, but I now accept it as fulfilling and enriching. Teaching and learning are intertwined and run in both directions – one must break the cultural barrier that the teacher has all the knowledge and the student some or none. It took a young medical officer to unravel a misconception I had for more than 20 years that chronic malaria and tropical splenomegaly syndrome were different entities.

We often do clinical teaching on cases we already know accompanied by its inherent biases. Teaching on cases we are blinded to is a mind-boggling experience. In the last few years, I have experimented and adventured with teaching on cases where I am blinded to the findings or diagnosis. Both the student and the teacher can learn a lot and we get better as we express our thoughts and disrobe our thinking processes openly. This to me is akin to practising clinical reasoning live.

Most of my initial clinical teachings concentrated on artificial situations where we selected “good cases” — this, unfortunately creates an artificial divide of what we see as clinicians and how patients present to us. I am even more convinced, over the years, that every case is a good case to teach; choosing the slant and emphasis in every situation is critical.

We tend to cram information to students, as much as I did in the past. Now, I ask myself before a tutorial or lecture on what is the primary target of my teaching. Teaching must be customised to the audience. I used to joke with my students in the early years whenever an examiner asks you for causes of a certain abnormality – a second-year student gives two, third-year student three and final year student gives five, as a rough rule. This joke highlights the need to avoid unintentionally submerging our students in a factual journey and overloading them, forgetting how we acquired skills in a graduated manner.

Leonardo da Vinci is attributed to suggesting that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication. Great teachers have a way of simplifying complex concepts. Nobel laureates Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein likened lipoprotein traffic to navigating the maze in the London underground system while explaining lipoprotein metabolism. Prober and Heath (2012) remind us of the importance of making lessons “stickier” by making it comprehensible and memorable. Efforts to make things “simple is often harder than complex”, as profoundly highlighted by Steven Jobs (as cited in Reinhardt, 1998).

IV. PRINCIPLES AND PHILOSOPHIES

Over the decades, I have gradually moulded myself into believing in some philosophical concepts on clinical teaching shared below:

- Clinical teaching can be likened to planting a seed in a soil (student in the health care environment). We need to ensure the presence of sunshine, rain (stimulus) and fertile soil (conducive environment); as in nurturing, the wind (pressure and currents) cannot be too strong. A clinical teacher must look after the student welfare in preventing burnout, disillusionment or wilting away.

- For busy clinicians, giving committed time and effort to teaching can be challenging. It is worthwhile reminding us that to be a “doctor” means “to teach”. With ownership, we never generally say we lack time or rewards to teach and guide. Sharing our experiences and difficulties make students feel they are in good company.

- Teachers must learn to squeeze the best out of their students rather than looking negatively at their lack of knowledge. Beneath every “F-student” is an “A student” waiting in line and time to pop-out! A teacher must take part-responsibility and embarrassment for students’ failures, as much as we take pride and pleasure in their successes.

- Teachers should take extra effort to simplify concepts and to remind themselves that if they face difficulty in understanding certain concepts, it is unreasonable to expect their students to grasp these same concepts easily.

- Teaching should not concentrate on voluminous facts that are so easily accessible. It must be customised to deal with diversity in the audience as well as cater to the level of expertise of the student. Clinical teaching should focus on clinical reasoning.

- We must be bold enough to try teaching methods to reflect the plasticity we have within ourselves to adapt, grow and regenerate our knowledge and its transmission.

V. CONCLUSION

Medical education has changed over the few decades that I have practised in. The fundamentals have remained – to train our doctors as future physicians and specialists. The core values must be preserved while stimulating progress incorporating new ways of practice. Experience and reflections are excellent tools in our armamentarium of methodologies. I have never regretted my adventure into clinical teaching.

Notes on Contributors

Professor Rajasoorya is a senior consultant, endocrinologist, Campus Education Director at Sengkang General Hospital; clinical professor at NUS School of Medicine; and adjunct professor of Duke-NUS Medical School. He has undertaken various leadership, administrative/advisory positions in medical education, curriculum development and is the recipient of numerous education and teaching awards.

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the inspiration, experience, and knowledge of my students, my patients and my teachers that has moulded my philosophy in teaching.

Funding

No funding was obtained in the preparation and production of the paper.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Reinhardt, A. (1998, May 25). Steve Jobs: ‘There’s sanity returning’. Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/businessweek

Prober, C. G., & Heath, C. (2012). Lecture halls without lectures – A proposal for medical education. The New England Journal of Medicine, 366(18), 1657-1659.

*C. Rajasoorya

Department of General Medicine,

Sengkang General Hospital,

110 Sengkang East Way,

Singapore 544886

Tel: +65 6930 2221

Email: c.rajasoorya@singhealth.com.sg

Published online: 7 January, TAPS 2020, 5(1), 70-75

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-1/SC2065

Carmel Tepper, Jo Bishop & Kirsty Forrest

Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University, Australia

Abstract

Bond University Medical Program recognises the importance of workplace based assessment as an integrated, authentic form of assessment. In partnership with a software company, the Bond Medical Program has designed and implemented an online Student Clinical ePortfolio, utilising a mobile-enabled, secure, digital platform available on multiple devices from any location allowing a range of clinically relevant assessments “at the patient bedside”. The innovative dashboard allows meaningful aggregation of student assessment to provide an accurate picture of student competency. Students are also able to upload evidence of compliance documentation and record attendance and training hours using their mobile phone.

Assessment within hospitals encourages learning within hospitals, and the Student Clinical ePortfolio provides evidence of multiple student-patient interactions and procedural skill competency. Students also have enhanced interprofessional learning opportunities where nurses and allied health staff, in conjunction with supervising clinicians, can assess and provide feedback on competencies essential to becoming a ‘work-ready’ doctor.

Keywords: Authentic Assessment, Interprofessional Learning, Technology-Enhanced Learning, Feedback, Workplace-Based Assessment

I. INTRODUCTION

The medical education community is rapidly embracing workplace based assessment (WBA) as a more authentic form of assessment of medical students’ clinical competence. These clinical interactions are complex, with integrated competencies observed in real-life settings. For the safety of patients, however, it is essential that medical schools have evidence that their graduates have attained sufficient standards in core skills and activities as indicated by their relevant accrediting institutions’ graduating doctor competency frameworks. This includes evidence not only of sufficient maintenance of compliance documentation, attendance in clinical settings and teaching sessions, but also the ability of the student to interact competently with a variety of patients.

Student clinical placements within medical schools are often undertaken in multiple locations with a variety of clinical supervisors. At Bond University, Australia this process involves over 150 locations with up to 800 clinical supervisors observing, assessing and providing feedback on student performance. Previous manual, paper-based processes were inefficient, time-consuming, prone to error, and limited the opportunity for real-time feedback to students. Difficulty aggregating information resulted in difficulty making pass-fail decisions on student performance on rotation and delayed intervention for students requiring remediation for either compliance, attendance or clinical performance.

Whilst clear and validated documentation of proficiency required of a “work-ready” graduate is often challenging to obtain, this aggregation of multiple data points to build a more complete picture of student competence is central to the concept of programmatic assessment (van der Vleuten, 2016). A portfolio of evidence with timely feedback on performance is seen as essential for demonstrating the growing development of student clinical skills.

An electronic, or ePortfolio, represents the technological evolution from paper-based to electronic clinical assessments (Garrett, McPhee, & Jackson, 2013). There are multiple ePortfolios and learning management systems available which can be used in the workplace and electronically collect in-progress assessments and accomplishments (Kinash, Wood, & McLean, 2012). Some ePortfolios also allow students to manage continuing professional development. Bond Medical Program, however, sought to develop an ePortfolio specifically designed for undergraduate medical students that could aggregate not only attendance and compliance but also competency assessment data in a meaningful way to build an accurate picture of student competency in the hospital setting.

The aim of this short communication is to describe why and how a new version of a bespoke electronic portfolio was designed and implemented.

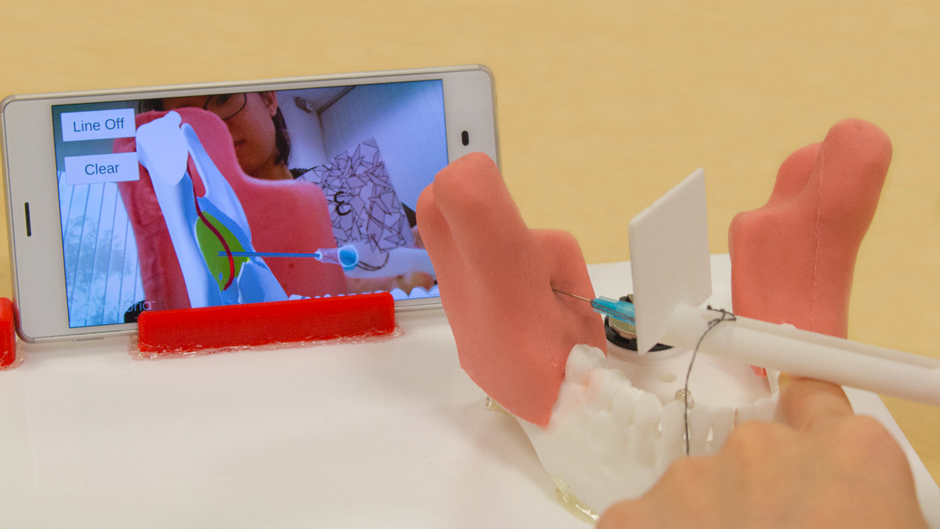

II. METHODS

Bond University partnered with a software company, which had healthcare experience, in the development of a digital student Clinical ePortfolio. The business requirement specification was for a fully mobile-enabled, secure, digital platform available on any device from any location that would allow a range of clinically relevant WBAs to be captured by clinicians “at the bedside” with the ability to provide immediate feedback to students. In addition, the software was to contain a process for students to provide evidence of compliance documentation and attendance at compulsory teaching sessions and on rostered placement shifts. The initial plan was to replicate all paper-based processes onto an electronic platform. The development of the software was iterative to the needs of the university using a road cycle improvement process. An app-based product was developed to house the clinical portfolio.

| Feature | Benefit | Replacing |

| Tablet and mobile phone-enabled clinical assessment | Readily available, user-friendly, allows for opportunistic assessment

Guest assessors (allied health and nursing) can participate in medical student education |

Paper assessment which had to be collected and collated |

| Compliance | Simple to scan and upload by students

Dashboard shows aggregate of compliance completion to ensure all required documentation has been provided |

Time-consuming, laborious paper trail of compliance documentation |

| Attendance with GPS tracking | Students take responsibility for being on rotation when rostered

Specific number of absences can trigger early student support processes Accurate record of which students attended compulsory classes |

Paper sign-on forms |

| Dashboard – Summary data | Student and clinical staff can view aggregated summary data showing attendance, compliance, student patient logs and WBAs | Multiple individual paper WBAs that could not be aggregated |

| Personal student learning | Students can log personal patient interactions as a record of their learning on rotation | Paper patient logs |

| Learning Modules with associated procedural skills assessment | Students watch a ‘best-practice’ learning module, demonstrate their understanding by answering a short quiz and then generate an assessment for a clinical supervisor. The clinical assessor guides and observes the skill performance and then provides a ‘trust level’ competency rating. Students can repeat the assessment until competency achieved | Skills performed in hospital setting not formally captured |

| Feedback to student | Voice recorded or typed, feedback is provided to student as soon as submitted by the assessor – timely and relevant to the performance | Verbal feedback or occasional comment on a form |

| CPD | Students can log personal continuing professional development to capture more fully their learning journey |

Table 1. Bond eportfolio features

In August 2017, the compliance portion of the portfolio was piloted with a single clinical year cohort of medical students and supervisors. In 2018, attendance and WBAs were conducted at the bedside of patients across all clinical years.

Delivering the project across many sites required the support of all supervisors, along with timely stakeholder engagement, and change management considerations. The needs of busy clinicians were surveyed, and a low-key launch by way of an online training video was preferred by the majority, with face-to-face on-site training available upon request. There are several barriers to timely feedback in the busy clinical environment with ‘opportunistic assessment’, multiple demands on clinician time and multiple students and/or trainees under supervision at any one time (Algiraigri, 2014). Feedback using the ePortfolio can be provided in the moment, recorded as either typing or voice recording and reviewed by students within their own time. Feedback from clinicians described it as “easy to complete on the go” and “easy to assess then and there (at the bedside)”. Table 1 describes the features and benefits of the Bond ePortfolio.

An example of the compliance dashboard, and the assessment portfolio front page is shown in the Appendix.

III. RESULTS

The new platform successfully delivered the required features through the Bond Student Clinical Portfolio. The Portfolio is accessible to both student and supervising clinicians using mobile phones or office desktop computers. Students indicate their attendance using a GPS geolocating attendance application. Compliance documents, clerked cases, reflections and other assessment components including the final in-training assessment are uploaded for supervisor assessment, whilst Mini-Clinical Evaluation Exercises are now completed by supervisors using a mobile phone at the patient bedside. All assessments are housed in one cloud-based portal, accessible to the decision-making committees.

An added advantage of this system is improving student digital literacy and self-directed learning, assisting them to become familiar with the process of self-documenting evidence of competence and skills obtained a valuable and highly sought-after skill for a graduated doctor.

A. Workplace Based Assessment

Evaluation of the 2018 pilot demonstrated significant efficiencies in documentation collection of WBA. Previously, professional staff would have collated 2,350 components of high-stakes assessment per year to be reviewed and presented to the Board of Examiners (BoE). Faculty can now track student progress during clinical rotation, with a process in place to identify students who require additional support to succeed. Faculty receive automatic notifications for review of submitted assessment items. During meetings of decision-making committees such as the BoE, student assessment items can be viewed by the committee to verify students who are borderline or those who receive commendations.

B. Attendance

Key members of the medical programme have a ‘dashboard’ on their homepage with ‘live’ attendance data. The Professional Staff Team can run reports when required but the platform will monitor students who meet the nominated ‘concern’ percentage of missed sessions which notifies the team that a support email may be required. In our experience, concerns around student well-being often present with non-attendance patterns. Supervisors in the clinical setting can now electronically track the progress of students allocated to their teams during rotations. In addition, they can identify students who require additional support in a timelier manner, helping to provide the best education experience possible.

C. Feedback

The clinicians’ ability to utilise their preferred method of feedback delivery allows flexibility and improved engagement in the process. For instance, the ability to voice record was introduced, enabling students to immediately access assessor feedback. This has resulted in increased communication between students and their assessors and a very positive response from the student body.

Feedback on students’ experience of this platform has been sought through ongoing discussion with the initial pilot group, and regular updates on their learning management system, and representative year specific feedback through staff-student liaison committees. The attendance monitoring has had mixed reviews from students who “appreciate not having to sign in on paper” but have been impacted by technical issues around non-syncing with certain mobile devices.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our belief is that assessment within hospitals will encourage learning within hospitals. Our intention is to remove Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) from the final year assessment to be replaced with authentic WBAs that are reliable and valid. OSCEs will continue to be used in the earlier years of the medical programme. There may be limitations as the very nature of the hospital environment is opportunistic. Students will have multiple patient (data) interactions to support their developing portfolio with evidence of competencies achieved. Students can personalise their studies and identify areas of focus for skill development during placement, to ultimately build confidence in their work readiness as a day one doctor. Ultimately, assessment information “should tell a story about the learner” (van der Vleuten, 2016, p. 888).

This platform offers many advantages over other platforms. The selection of the software partner was a competitive process. A full needs analysis and tender process was performed which for brevity has not been presented here. The advantages over other platforms identified at procurement were the opportunity to customise and the ability to have all the processes (compliance, attendance, placement and assessment) on one platform. Subsequent advantages made clear after implementation, and not delivered by other platforms included; the ability for students to take the portfolio into the workforce, a dashboard for attendance, and working with a partner based in health care who understood all stakeholder requirements, with an emphasis on safe patient care.

The next step will be to utilise the platform for training, progression and maintenance of competency of procedural skills before graduation. Specific procedural skills, required by accrediting bodies and relevant to the year of learning, will be assigned to the student for completion during a rotation. The student, in addition to the routine clinical practice of for example intravenous cannulation, will observe an interactive learning module about that skill, complete a short assessment to test their understanding of the module, and the system will then generate an assessment assigned to a clinical supervisor. The student will then perform the skill on the patient and the supervisor will submit the completed assessment on a ‘trust level’ scale of competency (ten Cate, 2013). If the student is not yet able to perform the skill sufficiently independently, there are opportunities to practice and repeat the assessment until competency is obtained.

V. CONCLUSION

Digitising the processes for monitoring attendance, conducting and collating compliance documentation, clinical assessment and delivering feedback at sites of clinical exposure has created significant efficiencies in the delivery of our programme. Preliminary feedback indicates that this leads to a vastly improved student experience with real-time, enhanced feedback on assessment performance and timely student remediation to assist students in becoming safe and competent ‘work-ready’ doctors. Live updates that notify of absenteeism allow for more timely support and personalised care. The aggregation of data into one personalised student clinical ePortfolio will allow decision-making bodies to make intelligent and safe pass-fail decisions based on evidence of student clinical performance.

Notes on Contributors

Carmel Tepper is the Academic Assessment Lead at Bond University. She has a special interest in exam blueprinting, item analysis and assessment technologies.

Jo Bishop is the Academic Curriculum Lead and Associate Dean, Student Affairs and Service Quality at Bond University. Jo is an expert on curriculum planning and development and has a passion for enhancing the student experience.

Kirsty Forrest is the Dean of Medicine at Bond University. She has been involved in medical educational research for 15 years and is co-author and editor of several best-selling medical textbooks including ‘Medical Education at a Glance’ and ‘Understanding Medical Education: Evidence Theory and Practice’.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required.

Acknowledgements

An e-poster presentation on some of this work was presented at 15th anniversary APMEC and awarded a merit.

Funding

There is no funding involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

Other institutional uptake of the new designed Student Clinical Portfolio may financially benefit Bond University.

References

Algiraigri, A. H. (2014). Ten tips for receiving feedback effectively in clinical practice. Medical Education Online, 19(1), 25141. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v19.25141

Garrett, B. M., MacPhee, M., & Jackson, C. (2013). Evaluation of an eportfolio for the assessment of clinical competence in a baccalaureate nursing program. Nurse Education Today, 33(10), 1207-1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.06.015

Kinash, S., Wood, K., & McLean, M. (2013, April 22). The whys and why nots of ePortfolios [Education technology publication]. Retrieved from https://educationtechnologysolutions.com/2013-/04/the-whys-and-why-nots-of-eportfolios/

ten Cate, O. (2013). Nuts and bolts of entrustable professional activities. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5(1), 157-158. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-12-00380.1

van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2016). Revisiting ‘Assessing professional competence: From methods to programmes’. Medical Education, 50(9), 885-888. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12632

*Carmel Tepper

Faculty of Health Sciences,

Bond University,

14 University Drive, Robina QLD,

4226 Australia

E-mail: ctepper@bond.edu.au

Published online: 7 January, TAPS 2020, 5(1), 61-69

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-1/OA2152

Yoshitaka Maeda1, Yoshikazu Asada2, Yoshihiko Suzuki1 & Hiroshi Kawahira1

1Medical Simulation Centre, Jichi Medical University, Japan; 2Center for Information, Jichi Medical University, Japan

Abstract

Students in the early years of medical school should learn the skills of clinical site risk assessment. However, the effect of this training on clinically inexperienced students is not clear, and it is difficult for them to predict risks from a wide range of perspectives. Therefore, in this study, based on Kiken-Yochi Training (KYT) for risk prediction using what-if analysis, we examined how to expand risk prediction among clinically inexperienced medical students. We divided 120 students in the first year of medical school into small groups of seven to eight students. First, each group predicted risks in the standard KYT (S-KY) method, stating what risks exist in the illustrations. Next, they conducted a What-If KYT (W-KY) analysis, brainstorming situations that differed from the illustrations, and again conducted risk prediction. Three kinds of illustrations depicting medical scenes were used. Last, each student proposed solutions to prevent risks. In this study, we clarify differences in risk assessment tendencies for students between W-KY and S-KY. We found that students could predict a wide variety of risks about illustrations using W-KY, particularly risks about patient and medical personnel. However, for risks regarding management, clinical rules, and stakeholders, prediction in both S-KY and W-KY was difficult due students’ lack of knowledge, but solutions proposed by students covered these elements. Improving the format of discussion in W-KY might allow students to predict risk from a wider range of perspectives.

Keywords: Patient Safety Education, Undergraduate Education, Risk Assessment Skill, Kiken-Yochi Training, KYT, Risk Prediction, Clinically Inexperienced Medical Students

Practice Highlights

- This method helps inexperienced students brainstorm various scenarios needed for risk prediction.

- It was possible for students to practice risk assessment using What-If Kiken-Yochi Training (W-KY).

- Students could predict a wide variety of risks regarding patients and medical personnel using W-KY.

- It was difficult to predict management, clinical rules, and stakeholders’ risks even with W-KY.

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Issues on Patient Safety Education for Medical Students in Japan

In Japan, students enrol at medical schools immediately after graduating from high school. Safety education is often provided only at higher levels (4th or 5th year) in over 60% of medical schools in Japan, when clinical practice begins (Ishikawa, Hirao, & Maezawa, 2008). The following are the reasons: (1) educational practical methods for clinically inexperienced students are not specifically referred to in any guidelines or papers for students in the early years; (2) the educational effect on such students is unclear; (3) higher grade students have sufficient medical knowledge and can immediately apply their patient safety knowledge in clinical practice; and (4) there are few teachers specialising in medical safety, thus making it easier to determine the theme of education for higher grade students. On the contrary, 70% of medical schools only teach the minimum medical safety knowledge through lectures to students who have not yet practiced safety in clinical practice. The main contents of the lectures are analysis tools to prevent the recurrence of incidents, such as Root Cause Analysis and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis, legal responsibility knowledge, ethics, and infection (Mayer, Klamen, Gunderson, & Barach, 2009). However, as there are certain things that can be included immediately in clinical practice, it is difficult to keep students motivated.

The Telluride Interdisciplinary Roundtable (Mayer et al., 2009) and Lucian Leape Institute (2010) indicated that patient safety education should be conducted through a longitudinal curricular approach (including patient safety education in the curriculum of all grades), and it is important to educate lower grade students who have no clinical experience. This would enable students to learn the necessity and importance of patient safety knowledge, and to consider patient safety as implementation science while continuously practicing patient safety skills (Nakajima, 2012). Ishikawa et al. (2008) also emphasised the importance of continuous patient safety education, starting with beginner students so they can acquire good safety habits.

The Telluride Interdisciplinary Roundtable (Mayer et al., 2009) and Lucian Leape Institute (2010) outlined the patient safety competencies that students should acquire. In particular, students lack education on “non-technical skills” (Nakajima, 2012). Some of the necessary non-technical skills students need when they start working after graduation are risk assessment (situational awareness) skills to prevent accidents. This involves advance awareness of safety weaknesses and threats (risks) in the workplace or operations and the ability to avoid these risks (Doi, Kawamoto, & Yamaguchi, 2012; Takahashi, 2010). The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Patient Safety Curriculum Guide shows in Topic 6 (Understanding & Managing Clinical Risk) that students have to take correct action when they see an unsafe situation or environment (Walton et al., 2010). For example, when they see wet steps, they should predict the possibility of patients falling. WHO’s guide outlines the four-step process to manage clinical risks: (1) identify the risk, (2) assess the frequency and severity of the risk, (3) reduce or eliminate the risk, and (4) assess the costs saved by reducing the risk versus the costs of not managing the risk. However, this guide does not explain the teaching methods to enable students to identify or predict risks.

B. Educational Method Issues for Risk Assessment in Japan

Kiken-Yochi Training (KYT), a type of risk prediction training, was created by Sumitomo Metal Industries Co., LTD in 1974 (Chen & Mao, 2011), and helps workers understand risks in many kinds of industries, including the medical field (Doi et al., 2012; Hirokane, Shiraki, & Ohdo, 2010). KYT originated in Japan (Ito, Taguchi, & Fujinami, 2014) and has become a common safety management method (Ji, 2014). It increases workers’ awareness of risks and motivation to practice in a team and improves their problem-solving skills (Chen & Jin, 2012). KYT also enables workers to easily conduct on-site risk assessment. In a metal auto parts factory, the accident rate fell by six percent one year after the implementation of KYT (Poosanthanasarn, Sriboorapa, Fungladda, & Lohachit, 2005). In recent years, KYT use has also begun to spread in the medical field in countries other than Japan (Noor, Irniza, Emilia, Anita, & Suriani, 2016). In standard KYT (S-KY), the facilitator presents the learner with illustrations or photographs depicting the work site and guides them through four steps: (1) extracting items and risks considered to be dangerous in the illustration, (2) rating each item’s risk, (3) planning solutions, and (4) selecting urgent solutions (Japan Industrial Safety & Health Association, 2008). In particular, an important skill for medical staff at clinical sites is the ability to predict a myriad of risks from a broad perspective using the illustration in Step 1. More effective KYT has recently been designed, such as KYT using video instead of illustrations and KYT applications for tablets that enable students to easily take risk assessment training alone, such as during breaks, and KYT combining medical simulations of real clinic situations (Kadoyanagi, 2016; Nagamatsu, Miyazaki, & Harada, 2011; Takahashi et al., 2017; Yoneda et al., 2017).

However, in S-KY, the ability of experts to predict risks is higher than that of novices because novices do not have enough knowledge of important areas in the illustrations (Murata, Hayami, & Moriwaka, 2009). Hirokane et al. (2010) pointed out that experts are able to predict risks specifically in order to consider effective solutions to prevent accidents. Therefore, KYT is usually conducted for clinically experienced students, and is rarely implemented for inexperienced students. The reasons are as follows: (1) in S-KY, risk prediction in the illustrations is limited to “specific circumstances”; (2) if medical students practice risk prediction using only these illustrations, they cannot accurately identify risks at clinical sites when they encounter a situation different from the “specific circumstances” in the illustration in the future; and (3) if teachers use illustrations of scenes from non-medical sites to avoid the inability to predict risks in clinically inexperienced students who do not have enough medical knowledge, it is difficult for students to link the risk prediction content with actual clinical sites, to become motivated to learn, and to obtain educational effects from the training.

C. Hypothesis: What-If KYT (W-KY) Applicability

What-If analysis is used as a brainstorming method. It is widely used in the field of service design and brainstorms what kind of things will occur if a particular situation changes (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2012). Based on this method, Mochizuki and Komatsubara (2016) propose a step 0 prior to the existing risk assessment in KYT that is aimed at traffic safety, letting the participants identify various alternate situations: “If the situation of the illustration were different”. Next, the participants perform a risk assessment for each situation developed in Step 0. For example, the facilitator shows participants illustrations depicting sunny daytime “driving scenes on a straight road”. Participants conduct what-if brainstorming and consider various situations, such as “if the weather is different from the illustration”, “if it was night-time”, or “if it is a mountain pass”. They then conduct a risk assessment for each situation. This modification is called the W-KY. The subsequent steps are the same as the S-KY (Steps 1 to 4). By adding Step 0, participants are then better able to predict various risks from the illustrations, and their risk sensitivity increases.

Based on these articles related to S-KY and W-KY, S-KY might be more feasible for clinically experienced students than inexperienced students. Therefore, W-KY might be feasible for clinically inexperienced students, because the What-If analysis (Step 0) might help students’ brainstorming. It also might increase motivation to practice and improve students’ problem-solving capabilities. The central question of this paper is whether the W-KY is effective and feasible for clinically inexperienced students. Existing studies have not adopted the W-KY to medical treatment, and the effect on clinically inexperienced students is unclear.

D. Purpose of This Study

In this study, based on the W-KY, we propose and implement a training method to help clinically inexperienced students predict risks. We also clarify differences in the risk assessment tendencies of students in W-KY versus the S-KY.

II. METHODS

A. Methods in W-KY

We conducted the S-KY and W-KY for 120 medical students half a year after admission in 70-minute compulsory classes. The purpose of these classes was to teach diversity of thinking and thinking of others through discussions in small groups of seven to eight people. The S-KY and W-KY were conducted over two classes (140 minutes). Specifically, the students conducted group work in the following order using three kinds of illustrations (Figure 1) depicting clinical sites. In our class, after individual students brainstormed ideas, they shared ideas with others and learned about the diversity of ideas.

Figure 1. Illustrations used in S-KY and W-KY (Courtesy of Japan Industrial Safety & Health Association [n.d.])

Step 1 (S-KY Step): Individual students predicted what risks exist in the three illustrations, then they used posters to share their prediction results with the group.

Step 2 (W-KY Step): Individual students brainstormed “situations that differed from the illustration” for each of the three illustrations. For example, in Illustration 1, one student thought of “a situation in which only one person was guiding the gurney”.

Step 3 (W-KY Step): Individual students predicted what risks exist in the situations they brainstormed in Step 2, then shared the results in their groups using posters.

Step 4 (S-KY and W-KY Steps): Each student considered solutions to mitigate the risks that they had predicted and submitted a report on them at the end of the class. Specifically, each student selected one risk considered to be the biggest risk in each illustration, and considered three solutions to prevent the risk.

B. Clarification of Differences in Risk Assessment Tendency of Students Between W-KY and S-KY

We compared the prediction results of S-KY in Step 1 and W-KY in Step 3 using the P-mSHELL model (Kawano, 2002). This model shows that factors of medical incidents are patient, management, software, hardware, environment, and liveware (individuals/ teams). P-mSHELL represents the initials of these factors. To evaluate the effectiveness of safety education, it is necessary to ensure that risks related to Human Factors can be predicted from a broad viewpoint. There are several models that explain the cause of Human Factors issues: Lewin’s equation model (human behaviour is determined by factors related to the person and their environment; Lewin, 1936), the 4M model (factors related to Man, Machine, Media, and Management), and Reason’s categories (factors related to patient and provider; task, technology, and tool; and team, environment, and organisation; Reason, 1997). All models consider both human and environmental factors as the background of Human Factors issues. Among these models, P-mSHELL is a highly detailed model that explains human and environmental factors in medicine, thus making it easy to evaluate the effectiveness of safety education. The P-mSHELL model is based on the SHEL model that has been used in analysis of Human Factors issues in aviation. Molloy and O’Boyle (2005) pointed out this model is useful in examining errors in clinical site, and may have some potential in training medical staff about Human Factors. Therefore, the P-mSHELL model is frequently referenced to understand human error in medical care. It is expected that the target students of this research will be able to predict the safety weaknesses (risks) in the clinical site from the point of view of P-mSHELL and to take preventative solutions. For this reason, this study verifies the educational effect by comparing the danger predicted by S-KY and W-KY using this model. We also summarise student brainstorming results in Step 2 “regarding situations that differ from the illustration” and examine its effect on student risk assessment. Then, we classify the solutions described in the report by students from the point of view of P-mSHELL.

C. Ethical Considerations in This Research

Regarding the ethical use of the results of S-KY and W-KY conducted in the class for research, we emphasised and explained to students that cooperation in this study was voluntary and that declining to cooperate would have no influence on their grades. We explained that students’ grades are scored based on the rubric described in the syllabus and that consent to cooperate in the research could be withdrawn at any time. It was explained that the results of this study may be published after processing, but the student’s personal information would not be revealed in the publication. The students entered their consent to use the results of S-KY and W-KY for this research in the e-learning system, Moodle, and 120 out of 123 students agreed to participate. In this research, we analysed data from students who agreed to participate. This study was considered exempt by the Jichi Medical University Review Board (protocol number 18-014).

III. RESULTS

A. Results of Predicted Risk by S-KY and W-KY

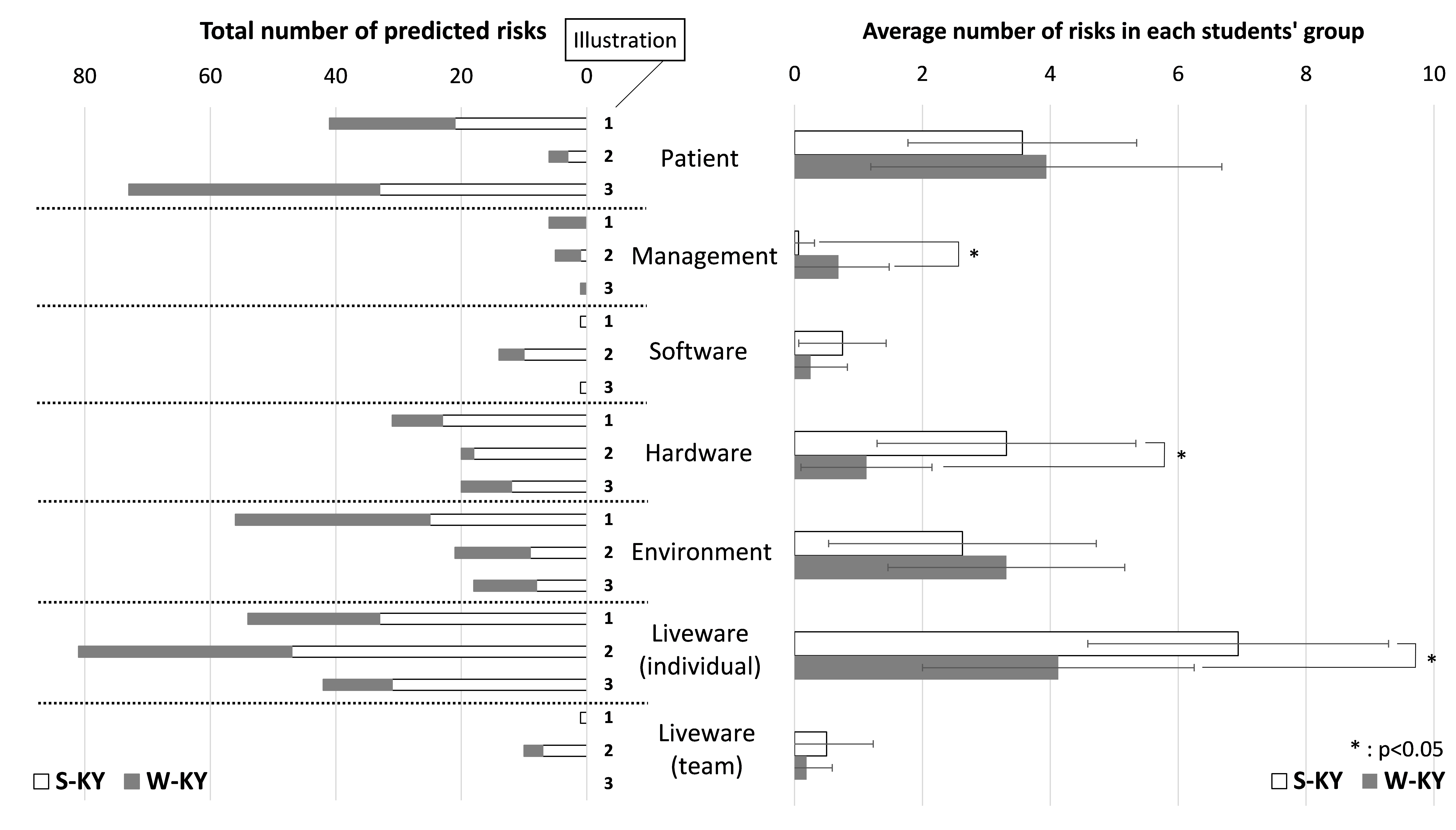

Figure 2 (left) shows the total number of risks predicted by students for each illustration. In addition, Figure 2 (right) shows the average number of predicted risks for each student group. We clarified the difference between S-KY and W-KY using the students’ t-test.

First, students were able to predict a variety of risks regardless of whether S-KY or W-KY was used. With the exception of liveware (team) in Illustration 3, the risks for all elements of P-mSHELL were predicted. In addition, the risks varied widely in the ease of prediction by the illustration (Figure 2, left). In Illustration 1, patient, environment, and liveware (individual) risks were predicted in S-KY and W-KY. In Illustration 2 predicted risks were liveware (person), and in Illustration 3, patient. Risks related to management, software, and liveware (team) were very few in both S-KY and W-KY, and for some illustrations, student groups predicted no risks in some categories.

Despite W-KY being implemented after S-KY, patient and environment risks had approximately the same number in S-KY and the W-KY. The number of liveware (individual) and hardware risks predicted in W-KY was less than in S-KY—liveware (individual): t(16) = 3.47, p < .05; Hardware: t(16) = 3.44, p < .05. In W-KY, many were predicted in Illustrations 1 and 2.

For example, in scenario 1, risks such as, “staff transferred patient to the wrong room” and “the patient would be injured if the stretcher breaks” were predicted in S-KY. In W-KY, risks such as, “If the corridor is dark, staff are not able to notice changes in the patient’s condition”, “If the corridor gets wet, the stretcher may slip and fall”, “If the patient is elderly, the patient will fracture a bone due to impact”, “If the patient has dementia, he forgets about treatment when he wakes up and removes the infusion tube himself”, and “If the staff is busy, he forgets to change the drip, emptying the drip and harming the patient” were predicted.

Figure 2. Result of predicted risk by S-KY and W-KY (Based on the classification of P-mSHELL)

Figure 2. Result of predicted risk by S-KY and W-KY (Based on the classification of P-mSHELL)

B. Results of Brainstorming Situations That Differed from the Illustration in Step 2

Table 1 shows how the students brainstormed situations that differed from each illustration in Step 2 as mentioned in the Methods section (refer to A. Methods in W-KY). In Table 1, the situations brainstormed by the students are organised based on each element of P-mSHELL.

First, the situations brainstormed by the students were remarkably diverse regarding patient, liveware (individual), hardware, and environmental factors. Although the number of liveware (individual) and hardware risks predicted in W-KY were less than in S-KY, the liveware (individual) risks predicted in W-KY were diverse.

On the other hand, the situation about management, software and liveware (team) were small in number (Table 1). This is also reflected in the low number of risks predicted for these factors (Figure 2).

| Description in the illustration | Situations brainstormed by students (in W-KY) | |

| Patient | One adult patient | Infants, elderly patients, infections, dementia, allergies, acute diseases, tall, obese patient, angry, sleeping, turning over many times, excited, removing the tube, patient with the same name exists, the patient’s family (child) is present, the operation is refused for religious reasons |

| Management | N/A | Staff shortage |

| Software | Directions | Mistaken, hard to read handwriting |

| Hardware

|

Gurney | Broken, screw loose, unstable |

| Bed | Narrow, nurse call button is broken | |

| Drip stand, tube | Fall, break, clogged tube, multiple drops exist | |

| Environment | Corridor | Crowded, wet in the rain, slippery, narrow, blackout |

| Room | Dark, bumpy, flickering, large number of patients | |

| Workspace | Messy | |

| Liveware (individual) |

One nurse | Fatigue, poor health, infection, lack of sleep, after working late, rushing, novice, lack of technology, lack of knowledge, presbyopia |

| Liveware (team) |

Nurse | Does not exist, bad relationship, noisy |

Table 1. Results of brainstorming in Step 2 about “situation different from illustration”

C. Solutions Proposed by Students to Mitigate the Risks

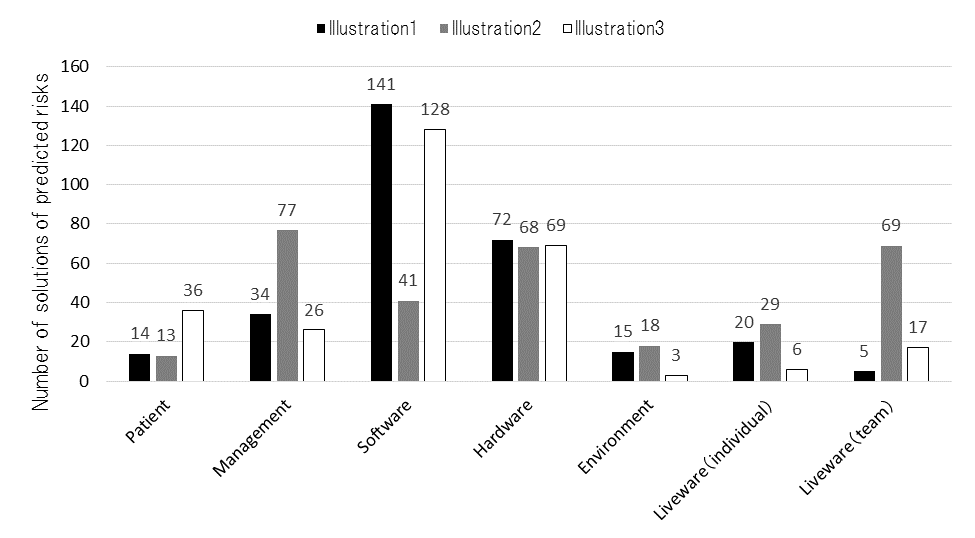

In Figure 3, the solutions proposed by the students to mitigate the risks were classified by P-mSHELL. In addition, Table 2 shows a concrete example of solutions for each element. In this paper, it has not been possible to analyse what kind of solutions were considered for each risk in S-KY and W-KY because students considered solutions in a post-class report.

In both S-KY and W-KY, students were able to consider a wide variety of solutions for almost all P-mSHELL factors. Although predicted risks related to management, software, and liveware (team) were very few, students were able to propose a lot of solutions related to them. There were many solutions, especially for software and hardware. For example, for software, double-checking, pointing and calling (occupational safety method), and creating a checklist were suggestion; in hardware, changing the shapes and names of the medicine in order to make it difficult to make mistakes was proposed.

| Patient | Patient participation Patient education Counseling, informed consent |

| Management | Work-life balance Rest management Staffing |

| Software | Creation of procedures (patient transport, patient fixation, dispensing, medication, patient assistance, etc.)

Examination of check method (pointing and calling, etc.) Efficiency of preparation work |

| Hardware

|

Improvement of hospital facilities

Improvement and computerisation of medical records and prescriptions Change of medicine shape and name Automation |

| Environment | Sorting Setting-in-order Shining Standardising Sustaining the discipline |

| Liveware (individual) |

Education and training Counseling Studying medical knowledge Attention/concentration Multitasking prevention Qualifications |

| Liveware (team) |

Good communication Thorough double check Establish a contact system |

Table 2. Examples of solutions considered by students

Figure 3. Result of solutions of predicted risks (based on the classification of P-mSHELL)

Figure 3. Result of solutions of predicted risks (based on the classification of P-mSHELL)

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Similarity and Difference Between S-KY and W-KY

Students should be able to predict risks in all elements of P-mSHELL as they can minimally experience the risks of each element in a clinical site. The results show that the elements of risk in P-mSHELL in both S-KY and W-KY are similar. Students could predict many patient and environment risks. These elements were drawn in advance in each illustration as shown in Figure 1. In other words, it was possible for students to brainstorm risks regarding stakeholders and medical devices drawn in illustrations in S-KY and W-KY. One of the possible reasons students could predict several patient and environment risks is that even a clinically inexperienced medical student has experience as a patient or has experienced the same situation (e.g., fatigue, immorality, lack of knowledge, etc.) as liveware (individual). Kazaoka, and Otsuka (2003) indicate that nursing students tend to recognise risks that they can imagine as their own and consider important, such as liveware (individual). On the other hand, management, software, and liveware (team) risks were very few in both S-KY and W-KY. The number of patient, environment, management, software, and liveware (team) risks had approximately the same number in S-KY and W-KY. The number of liveware (individual) and hardware risks in W-KY was less than in S-KY. In other words, it is considered that W-KY may cover the risks that can be predicted with S-KY.

Next, we discuss the strengths of W-KY. The risk description by students in W-KY included the risks and information related to various situations. Particularly in W-KY, students were able to brainstorm a wide variety of situations regarding patient, liveware (individual), hardware, and environmental risks (Table 1). This tendency is the same as the risk prediction tendency of S-KY and W-KY, and the reason for this tendency is considered to be the same. In W-KY, for example, regarding the transporting of stretchers, inexperienced students could consider various dynamic situations that can cause accidents, such as wet corridors, crowded corridors, violent or acutely ill patients, and lack of human resources. These situations that students brainstormed, listed in Table 1, are paraphrased as medical accident risks. In other words, in S-KY, students predict only medical accidents related to illustrations (results of accidents), whereas in W-KY, students were able to predict many high-risk situations that can cause medical accidents, and medical accidents (possible cause and results of accidents).

Through W-KY, students may have learned what a high-risk situation is and that clinical tasks can change into various dynamic situations that differ from illustrations. As a result, they may have learned the necessity of risk prediction in clinical practice and the significance of learning patient safety. These points will be explored in future research. In addition, Hirokane et al. (2010) pointed out that it is very important to predict risks specifically to prevent accidents. Therefore, it is possible that even inexperienced students can do this by using W-KY.

B. Limitations of W-KY

Only few students could predict risks management, software, and liveware (team) in S-KY and W-KY. However, students were able to consider solutions for almost all P-mSHELL factors (Figure 3). Contrary to the results of predicting risks in W-KY and S-KY, students were able to propose many solutions related to the aforementioned elements. This means that students can brainstorm these elements. In particular, regarding the software, students can mention the establishment and thoroughness of rules and manuals when planning solutions, and can think sufficiently from that viewpoint. Therefore, improving the format of discussion in W-KY may allow students to predict risks from a wider range of perspectives.

V. CONCLUSION

In this research, we proposed and implemented a training method to help clinically inexperienced students predict various risks. W-KY (brainstorming situations in illustrations and predicting risks based on them), as implemented in this research, allowed clinically inexperienced students to predict risks. We found that the elements of risk in P-mSHELL in both S-KY and W-KY are similar. Students could predict many patient and environment risks. However, with regard to management, software, and liveware (team) factors, S-KY and W-KY appeared to be difficult.

In addition, W-KY enables the prediction of high-risk situations that can cause medical accidents. This is important for predicting risks—including possible causes of accidents—specifically to prevent accidents.

In summary, W-KY can cover the risks that can be predicted by S-KY, and also allows students to consider various dynamic high-risk situations that can cause accidents. This suggests that W-KY can be used instead of S-KY.

In this study, it was not possible to analyse what kind of solutions to prevent risks were considered for each risk in S-KY and W-KY, as students considered solutions in a post-class report. Because this study was conducted as part of the class, we could not obtain data of student perspectives on learning outcomes or transferring learning to practice. The first-year medical school students in this research have the opportunity to receive medical safety education again when they are in the fourth year. At that time, we have plans to provide opportunities for practicing skills by applying W-KY in clinical practice, which will be explored in a future research. In addition, comparisons between students with clinical experience and inexperienced students and between W-KY/S-KY and other educational programs on accident prevention are also future topics of this research.

Notes on Contributors

Yoshitaka Maeda, PhD, is a research associate at the Medical Simulation Center at Jichi Medical University, Japan. He conducted the research supervision, class implementation, and data analysis.

Yoshikazu Asada, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Center for Information at Jichi Medical University, Japan. He contributed to the data compilation regarding the effect of this education.

Yoshihiko Suzuki, MD, is an assistant professor at the Medical Simulation Center at Jichi Medical University, Japan. He contributed to the design and planning of this class.

Hiroshi Kawahira, MD, is a professor at the Medical Simulation Center at Jichi Medical University, Japan. He gave advice on writing this paper and on data aggregation.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Jichi Medical University Institutional Review Board (Protocol number 18-014).

Funding

There is no funding involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

Chen, Q., & Jin, R. (2012). Safety4Site commitment to enhance jobsite safety management and performance. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 138(4), 509-519. http://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000453

Chen, N., & Mao, Y. (2011). Specific statistics and control method study on unsafe behavior in Chinese coal mines. Procedia Engineering, 26, 2222-2229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2428

Doi, T., Kawamoto, K., & Yamaguchi, K. (2012). Difference in the level of patient treatment safety analysed by the years of experience of the radiological technologies. Nihon Hoshasen Gijutsu Gakkai zasshi [Japanese Journal of Radiological Technology], 68(5), 608-616. http://doi.org/10.6009/jjrt.2012_jsrt_68.5.608

Hirokane, M., Shiraki, W., & Ohdo, K. (2010). Hazard prediction activities for safety education. Doboku Gakkai Ronbunshuu F/JSCE Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 66(1), 55-69. https://doi.org/10.2208/jscejf.66.55

Ishikawa, M., Hirao, T., & Maezawa, M. (2008). Study of patient safety education for undergraduates. Igaku Kyoiku / Medical Education (Japan), 39(2), 115-119. https://doi.org/10.11307/mededjapan1970.39.115

Ito, K., Taguchi, H., & Fujinami, K. (2014). Posing questions during experimental operations for safety training in university chemistry experiments. International Journal of Multimedia and Ubiquitous Engineering, 9(3), 51-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijmue.2014.9.3.06

Japan Industrial Safety and Health Association. (2008). Sugu ni jissen shirīzu Anzen wo Sakidori Kiken Yochi [Practice series: Ahead of safety, risk prediction]. Tokyo, Japan: JISHA.

Japan Industrial Safety and Health Association. (n.d.). Iryō kango | kiken yobō kunren (KYT) muryō irasutoshīto-shū [Medical/Nursing | Risk prediction training (KYT) free illustration sheet collection]. Retrieved from https://www.aemk.or.jp/kyt/iryo/page/5

Ji, H. J. (2014). A study on safety culture construction for coal mine. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 644-650, 5949-5952. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.644-650.5949

Kadoyanagi, T. (2016). Shūdan sanka taiken-gata kōshū-yō kizai (dōga KYT)-tō no un’yō jōkyō ni tsuite (tokushū jukō-sha no tokusei ni ōjita kōtsū anzen kyōiku) (Operation of group training equipment [Video KYT]. [Traffic safety education according to the characteristics of the students]). Gekkan Kōtsū, 47(7), 44-55.

Kawano, R. (2002). Iryō risuku manējimento seminā tekisuto [Medical risk management seminar text]. Tokyo, Japan: Tepco Systems.

Kazaoka, T., & Otsuka, K. (2003). Study of nursing students’ recognition of the risks of medical treatment accidents: Using the scenario of role playing drug misadministrations. Journal of Japan Society of Nursing Research, 26(5), 133-143. https://doi.org/10.15065/jjsnr.20030912009

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10019-000

Lucian Leape Institute. (2010). Unmet needs: Teaching physicians to provide safe patient care. Boston, MA: National Patient Safety Foundation.

Mayer, D., Klamen, D. L., Gunderson, A., & Barach, P. (2009). Designing a patient safety undergraduate medical curriculum: The telluride interdisciplinary roundtable experience. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 21(1), 52-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330802574090

Mochizuki, R., & Komatsubara, A. (2016). Proposal of traffic KYT with using What-if analysis. The Human Factors in Japan, 20(2), 79-82.

https://doi.org/10.11443/jphf.20.2_79

Molloy, G. J., & O’Boyle, C. A. (2005). The SHEL model: A useful tool for analyzing and teaching the contribution of Human Factors to medical error. Academic Medicine, 80(2), 152-155.

Murata, A., Hayami, T., & Moriwaka, M. (2009). Visual information processing characteristics of drivers in prediction of dangerous situation-comparison among novice, expert and non-licensed person. In Proceedings: Fifth international workshop on computational intelligence & applications, 2009(1), 254-257. Hiroshima, Japan: IEEE SMC Hiroshima Chapter.

Nagamatsu, I., Miyazaki, I., & Harada, C. (2011). Kango kiso kyōiku ni okeru kiken yochi torēningu (KYT) wo toriireta iryō anzen kyōiku ni kansuru kōsatsu: Dōga jirei o mochiita puroguramu no kōka [A study on medical safety education incorporating risk prediction training (KYT) in nursing education: Effects of programs using movie]. Nihon kango gakkai ronbun-shū. Kango kyōiku, 42, 158-161. Retrieved from

https://iss.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I023685394-00?ar=4e1f&locale=e

Nakajima, K. (2012). 4. Patient safety and quality improvement education for undergraduate medical students. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi [Journal of the Japan Society of Internal Medicine], 101(12), 3477-3483. https://doi.org/10.2169/naika.101.3477

Noor, A. Y., Irniza, R., Emilia, Z. A., Anita, A. R., & Suriani, I. (2016). Kiken yochi training (KYT) in reducing accidents at workplaces: A systematic review. International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences, 3(4), 123-132.

Poosanthanasarn, N., Sriboorapa, S, Fungladda, W., & Lohachit, C. (2005). Reduction of low back muscular discomfort through an applied ergonomics intervention program. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 36(Suppl. 4), 262-270.

Reason, J. T. (1997). Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Aldershot, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Stickdorn, M., & Schneider, J. (2012). This is service design thinking: Basics-tools-cases. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: BIS Publishers.

Takahashi, A., Mishina, M., Takagi, M., Shimazaki, K., Ishida, T., & Umezaki, S. (2017). Taburetto tanmatsu wo mochiita anzen kyōzai no kunren kōka to anzen kanri e no ōyō: Teisō jūtaku kenchiku genba wo taishō to shite [Effect of safety teaching materials using tablet and its application to safety management: For low-rise residential building]. Specific research reports of National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, 47, 39-44.

Takahashi, R. (2010). Nontekunikkusukiru torēningu e no chosen [Challenge to non-technical skills training]. In K. Nakajima, & Y. Kodama (Eds.), Iryō anzen koto hajime [Beginning of medical safety] (pp. 36-51). Tokyo, Japan: Igaku Syoin.

Walton, M., Woodward, H., Van Staalduinen, S., Lemer, C., Greaves, F., Noble, D., … Barraclough, B. (2010). The WHO patient safety curriculum guide for medical schools. BMJ Quality & Safety, 19(6), 542-546. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2009.036970

Yoneda, T., Itami, K., Seki, K., Kawabata, A., Kubota, Y., Yasuhara, O., & Maesako, T. (2017). Changes in nursing students’ risk awareness and understanding of medical incidents after exposure to a simulated incident. Japan Journal of Educational Technology, 41(Suppl.), 17-20.

https://doi.org/10.15077/jjet.S41011

*Yoshitaka Maeda

Medical Simulation Center,

Jichi Medical University,

3311-1, Yakushiji,

Shimotsuke-shi, Tochigi, Japan

Tel: +81 285 58 7455

Email: y-maeda@jichi.ac.jp

Published online: 7 January, TAPS 2020, 5(1), 54-60

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-1/OA2095

Min Jia Chua1, Gen Lin Foo2 & Ernest Beng Kee Kwek2

1National Healthcare Group, Ministry of Health Holdings, Singapore; 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Woodlands Health Campus, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Mentoring is a vital component of a well-rounded medical teaching environment, as evidenced by its implementation in many residency programmes. This study aims to evaluate the perceived value of mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring to the orthopaedic surgery resident.

Methods: An online survey comprising multiple choice questions and scaled-response questions with a few open-ended questions was created and distributed to all residents, from residency years 2 to 5, within an orthopaedic residency programme in Singapore to gather their views on a tiered mentorship programme.

Results: 100% of surveyed residents responded. 68.4% of junior residents had a senior resident mentor while 84.8% of all residents had a faculty mentor. Junior residents generally viewed senior resident mentors as being crucial and beneficial for training, with scores comparable to those for faculty mentors. Residents who had mentors, in particular those who had chosen their own mentors, tended to be more satisfied than their counterparts. The most desired characteristics of mentors among the residents included approachability, willingness to share, being able to give feedback and experience. 66.7% of residents felt that near-peer mentorship should be required in the residency programme but only 30.3% of them felt that it should be formalised. 78.8% of residents surveyed felt that mentorship by faculty was required.

Conclusion: Residents viewed mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring as being beneficial and crucial to their orthopaedic residency training. We propose that an ideal mentoring programme should be tiered, allow choice of mentors and include near-peer mentoring as a requirement but not necessarily monitored.

Keywords: Orthopaedic Surgery, Resident Education, Mentoring, Medical Teaching, Tiered Mentorship

Practice Highlights

- Study to evaluate value of mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring to orthopaedic surgery resident.

- Residents viewed mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring programmes as being beneficial and crucial.

- Ideal mentoring programme should be tiered and allow choice of mentors.

- Near-peer mentoring should be a requirement but not necessarily monitored.

I. INTRODUCTION

Mentoring has long been a crucial element of effective resident medical education (Sambunjak, Straus, & Marusic, 2006), with many programmes adopting mentoring by faculty as an integral component of their residency programme. Various models of mentoring and types of mentoring activities have been described including didactic sessions, regular mentor-mentee meetings and group projects (Kashiwagi, Varkey, & Cook, 2013). The benefits of mentoring have also been shown in various studies, by aiding personal and professional development during residency, helping with

career preparation (Ramanan, Taylor, Davis, & Phillips, 2006), improving professional and social skills (increased self-confidence, improved communication skills; Buddeberg-Fischer, & Herta, 2006).

There is however, little data looking at how Orthopaedic residents view mentorship programmes (Flint, Jahangir, Browner, & Mehta, 2009). Furthermore, most studies look at mentoring by faculty with little emphasis on near-peer mentoring. In fact, a literature review has shown that no studies have looked at and compared the two entities in orthopaedic residency programmes.

In our residency programme, a tiered mentorship framework, where both mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring are practised, has been in place since 2014. In the former, a mentor of associate consultant grade and above who is in post-fellowship training will mentor a resident while in the latter, a senior resident mentor will mentor a junior resident two residency years below him or her.

The objective of having a near-peer mentorship framework in our programme was to bridge some of the gaps in traditional mentorship. In mentorship by faculty models, there will inevitably be hierarchical distance between mentors and mentees and residents may not feel as at ease approaching their mentors for certain issues. Furthermore, there may be a shortage of faculty members who are also strapped for time and may not be able to devote enough time for holistic mentorship of residents. These mentors are also further away from their residency training years and may not be able to understand some of the issues their mentees face in the current residency climate. It was envisaged that senior residents who are near-peers on the ground will be able to address some of the abovementioned shortcomings in the traditional mentorship model.

Currently, mentorship by faculty is formally monitored by the programme and mandates at least bi-annual meetings with a mentoring form to be filled in while near-peer mentorship is a self-directed initiative by the residents which is more informal with no stipulated frequency of meetings and no compulsory documentation under the residency programme requirements.

Residents were either assigned mentors or chose mentors at the start of the second year of their residency but due to various factors including efflux of faculty mentors or other administrative reasons, some residents do not have either senior resident or faculty mentors or both.

The objectives of this study were to 1) evaluate the orthopaedic surgery residents’ perception of mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring and 2) establish factors perceived as being important in mentors and a successful mentoring environment.

II. METHODS

An anonymised online survey with voluntary participation was administered to all orthopaedic surgery residents, from residency years 2 to 5 (R2 to R5), in our orthopaedic surgery residency programme. No identifiers were collected to ensure protection of the privacy of survey respondents. The choice of survey as the tool was to maximise response rates without compromising on data collection through comprehensive survey questions. There were two sets of questions evaluating the residents’ perception of mentoring by faculty and near-peer mentoring. The near-peer mentoring questions differed depending on whether the resident was a senior or junior resident and whether the resident possessed a mentee or mentor respectively. The mentoring by faculty questions varied depending on the presence of a mentor. The survey questions presented to the respondent were modified real-time based on their initial answers to the previous questions, hence eliminating questions which were not relevant.

These survey questions were adapted from a census survey conducted by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (Flint et al., 2009) on residents with regard to their experience in, and opinion of mentorship programmes and the prevalence of such programmes.

The questions administered were largely multiple-choice questions and scaled-response questions with a few open-ended questions. The multiple-choice and scaled-response questions covered the characteristics and perception of the mentoring environment (including how beneficial and crucial they found the mentoring programme, their satisfaction with the programme, their ideal mentorship framework, etc.), the perception of the value of mentoring (for instance to what extent they felt it supported their educational experience, aided with networking and making career decisions) and the characteristics of an ideal mentor. For the scaled response questions, respondents were asked to rate the importance of and their satisfaction with the different facets of their mentoring experience or environment on a scale ranging from 1 to 5.

The open-ended section of the survey allowed residents to air what they had achieved or hoped to achieve through the mentorship programme as well as general comments about the programme and suggestions for improvement.

Standard institutional review board procedures were followed and ethics board approval was obtained. Data analysis was performed using SPSS.

III. RESULTS

The survey was administered to a total of 33 residents across the residency batches from R2 to R5 in the residency year, with a response rate of 100%. Of the respondents, 19 were junior residents (8 R2 and 11 R3) and 14 were senior residents (6 R4 and 8 R5).

Of the junior residents, 68.4% (13/19) of them had senior residents while 78.6% (11/14) of the surveyed senior residents had junior resident mentees, with two of the senior residents having two junior resident mentees. 84.8% (28/33) of surveyed residents had faculty mentors (further details in Table 1).

| Residency year | Number with faculty mentors | Number without faculty mentors | Number with SR mentors (R2 and R3) or mentees (R4 and R5) | Number without SR mentors (R2 and R3) or mentees (R4 and R5) |

| R2 | 6/8 (75%) | 2/8 (25%) | 7/8 (87.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) |

| R3 | 11/11 (100%) | 0/11 (0%) | 6/11 (54.5%) | 5/11 (45.5%) |

| R4 | 3/6 (50%) | 3/6 (50%) | 4/6 (66.7%) | 2/6 (33.3%) |

| R5 | 8/8 (100%) | 0/8 (0%) | 7/8 (87.5%) | 1/8 (12.5%) |

Table 1. Breakdown of residents with faculty and senior resident (SR) mentors/mentees

Of the junior residents with a senior resident mentor, 53.8% (7/13) of them chose their own mentors while the rest had their mentors assigned. Of the residents with a faculty mentor, 60.7% (17/28) of them chose their own mentors. 69.2% (9/13) of junior residents met up with their senior resident mentors at least twice a year while 82.1% (23/28) of residents met up with their faculty mentors at least half-yearly or more frequently.

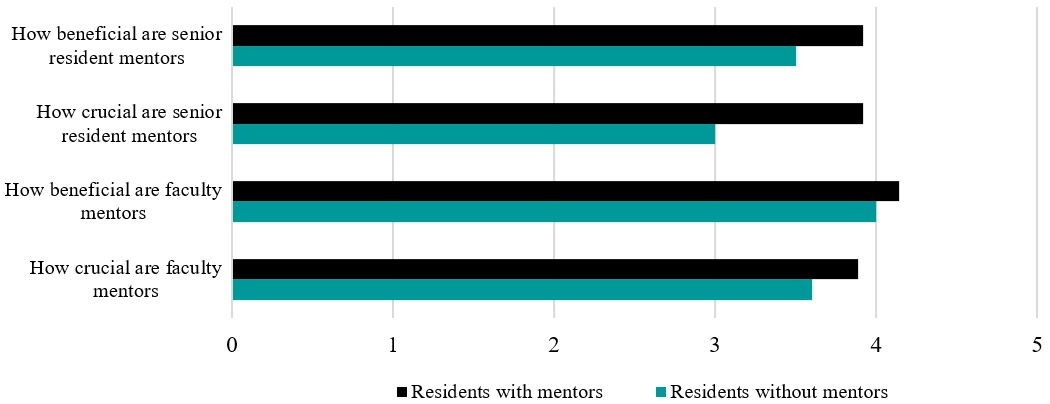

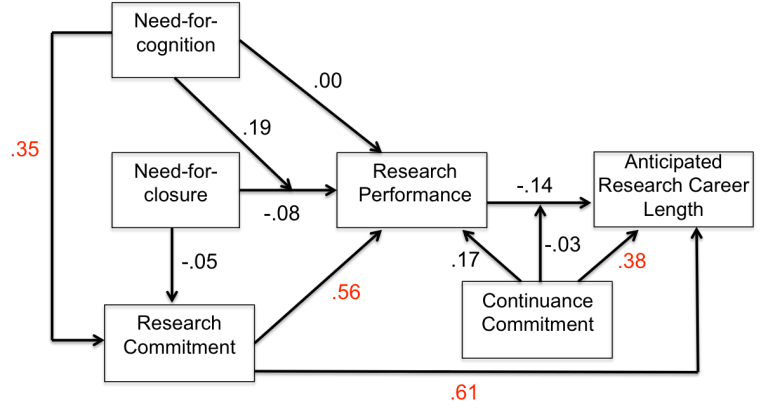

It was found that junior residents viewed senior resident mentors as being moderately beneficial and crucial to their training, with average scores of 3.92 on a scale of 1 to 5 (Figure 1). Of note, it was found that residents with senior resident mentors viewed near-peer mentorship as being more crucial and beneficial compared to their counterparts without senior resident mentors. Similar results were also echoed by the residents regarding their faculty mentors, with average scores of 3.89 and 4.14 for how crucial and beneficial faculty mentors were to residents with mentors and average scores of 3.6 and 4.0 for residents without mentors.

Figure 1. Chart showing how crucial and beneficial residents viewed senior resident and faculty mentors

In terms of satisfaction levels with the mentoring programme, residents with mentors (senior resident and faculty mentors) were also more satisfied with the mentoring programme than their peers without mentors, with average scores of 4.31 and 4.33 for residents with senior and faculty mentors respectively compared to average scores of 3.75 and 4.00 for residents without senior and faculty mentors.

A further subgroup analysis yielded that respondents with a self-selected mentor from both the senior resident and faculty mentor groups had higher scores for satisfaction levels (4.28 and 4.41 respectively) compared to those who had assigned mentors (4.16 and 4.20). Those with self-selected mentors in the faculty mentor group also felt that their mentor aided them more in supporting their educational experience and in making career decisions.

84.6% (11/13) of junior residents who had a senior resident mentor felt that their senior resident mentor was able to provide them with advice about career, employment, or difficult cases in the future while 89.3% (25/28) of residents with faculty mentors felt the same about their faculty mentors.

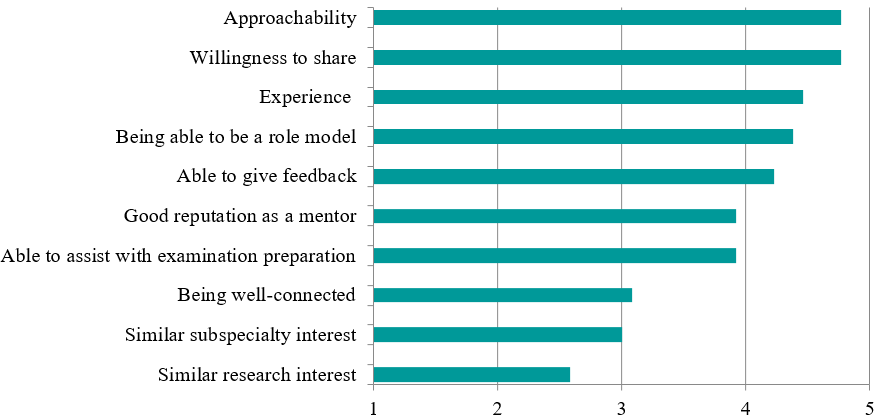

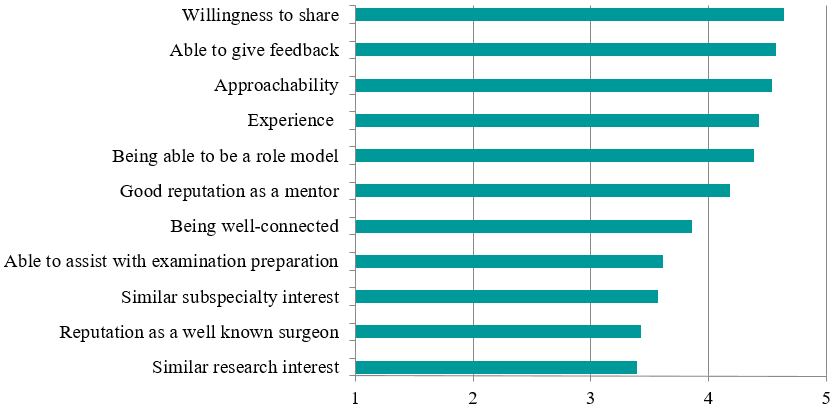

In terms of desired characteristics in a senior resident mentor, approachability, willingness to share and experience were the top three most desired characteristics (Figure 2A). Similar results were echoed in the results for faculty mentors, with ability to give feedback also highly valued (Figure 2B).

66.7% (22/33) of all residents felt that near-peer senior resident mentoring should be required in the resident programme but only 30.3% (10/33) thought that it should be formalised. Some of those who felt that near-peer mentoring should not be required expressed that they would like it to be up to the individual resident and that residents who are in need would approach senior residents directly of their own accord. 78.7% (26/33) of residents surveyed were of the opinion that faculty mentorship by faculty was required. Those who felt that faculty mentorship should not be required offered reasons including the hectic schedule of consultants and the unpredictable flow of faculty members into the private practice which would make it difficult for residents to maintain the same mentor throughout residency training.

Figure 2A. Chart depicting the desired characteristics scores in senior resident faculty mentors, ranked from most to least desired