Reflections on an interdisciplinary curriculum and pedagogical approaches in a public health course

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 54-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/CS2150

Julian Azfar & Rayner Kay Jin Tan

Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

The notion of interdisciplinary health(care) education is an emerging, though not novel concept (Allen, Penn, & Nora, 2006). The module Social Determinants of Health was introduced in the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health in 2018. The module covered important foundational concepts in the study of social determinants of health and explored examples of such determinants over 13 weeks. The module adopted an interdisciplinary approach to public health, drawing from biomedical, psychological and sociocultural perspectives informed by both the natural and social science disciplines. Coursework took the form of student-led seminars, opinion editorial (Op-Ed) and reflective essays, and a fieldwork project involving a chosen group in the community. While the adoption of such an interdisciplinary approach, or the use of the chosen pedagogical approaches are not novel, we present our reflections on the implementation of a novel, interdisciplinary course in public health for undergraduates in Singapore who do not have prior knowledge or expertise in the subject area.

II. AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FRAMEWORK

Past literature on interdisciplinary pedagogies have highlighted the importance of introducing interdisciplinary subjects in the curriculum, drawing on students’ varying backgrounds or disciplines in collaborative learning, and the focus on problems or issues instead of concepts (Friedow, Blankenship, Green, & Stroup, 2012), which have been incorporated in the present module. For example, module content was divided into three sections: “Environments and Communities”, “Globalisation and Work” and “Culture and Being”, providing opportunities for the exploration of public health issues from diverse perspectives. In addition, the focus on student-led seminars and essays, which emphasised the application of concepts to case studies or real-world contexts, helped further students’ understanding of the social determinants of health.

III. ASSESSMENT AND PEDAGOGICAL APPROACHES

The module’s teaching and learning approach was anchored in three main principles – constructivism, critical thinking and questioning, and experiential learning.

A. Constructivism

Constructivism, as a learning theory, posits that individuals engage in meaning-making through interactions between new and their pre-existing knowledge (Piaget, 1971). Each lesson began with a student seminar exploring a guiding question related to the week’s topic, followed by a lecture. Students were given an opportunity to construct their own understandings of the topics based on the assigned readings and compare these interpretations to those of the teacher. In addition, as part of individual written assessment, the Op-Ed and reflective essays further built on the constructivist approach by enabling students to formulate and defend their own judgments in response to other author’s arguments in the Op-Ed essay, as well as synthesising content meaningfully for the reflective essay.

B. Experiential Learning

Experiential learning, which emphasises the role of engagement with real-life experiences and consequences for learning (Kolb, 1984), was also a key feature of the course. To encourage preliminary insights into the necessity for experiential learning in the understanding of social determinants of health, guest speakers such as academics, non-governmental organisation representatives, researchers and even Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioners provided students with first-hand insight into their work and the social contexts of health in Singapore and beyond. The end-of-semester fieldwork project was also an opportunity for students to apply concepts in a relevant way by exploring how social determinants implicated health outcomes for a chosen community in Singapore.

C. Critical Thinking and Questioning

Critical thinking and questioning was an approach that undergirded the conduct of lessons, as well as the different modes of assessment in the module. Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956), for example, was used to scaffold questioning in teacher-led discussions and student seminar presentations. Particularly, in presenting their fieldwork projects, students were also assessed on the types of questions they fielded to presenting groups and the ability to defend their own arguments. Students were tasked with the responsibility of driving the process of class discussions, with the teacher only playing the role of a facilitator.

IV. REFLECTIONS ON COURSE EFFECTIVENESS

Both quantitative and qualitative feedback were obtained from students following the end of the course. Of the 73 students who had taken the course and were invited to provide feedback, a total of 32 students responded (43.8% response rate). Quantitative feedback focused largely on the effectiveness of the course instructors and did not yield rich insights into the effectiveness of the course relative to the qualitative feedback, and thus are omitted here. Qualitatively, students were asked to provide feedback on what they felt were positive aspects of learning in the course. Thematic analysis of the qualitative feedback generated three specific areas where students felt they were positively impacted; firstly, opportunities for creative thinking via assessment methods were favourable; secondly, real-world application of content helped to sharpen knowledge, skills, values; and lastly, flexibility in assessment and choice of topics engaged students more. A summary of these themes and corresponding quotes may be found in Table 1.

|

Themes |

Corresponding quotes |

|

Opportunities for creative thinking via assessment methods were favourable |

“Creativity as a point of marking for presentations, I feel that it stretched our brains and allowed me to think out of the box.” |

|

Real-world application of content helped to sharpen knowledge, skills, values |

“Raised my social awareness of many issues… applicable to our daily lives.”

“Something about health we can share with family and friends…” |

|

Flexibility in assessment and choice of topics engaged students more |

“Seminar-style… presentations were interesting…”

“The module is interesting because it allowed me to explore various aspects of health.” |

Table 1. Themes and corresponding quotes from qualitative responses as positive feedback on design, pedagogy and assessment of the course

V. CONCLUSION

Social Determinants of Health is establishing itself as a popular course amongst undergraduates from different backgrounds. This stems from the constructivist approach that has informed course design, as well as opportunities for critical thinking and questioning, and authentic experiences in teaching, learning and assessment. It is envisioned that by making more disciplinary connections and scaffolding critical thinking and communication throughout the module, the course will continue to enrich the learning experiences of undergraduates from an even more diverse range of specialisations.

Notes on Contributors

Julian Azfar is currently an instructor at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. He teaches courses related to the health humanities and is interested in using interdisciplinary curricula to promote critical thinking, perspective-taking and an appreciation of diversity in his courses.

Rayner Kay Jin Tan is a PhD student at the Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health. He has assisted in the planning and teaching of Social Determinants of Health and has been a key facilitator of learning activities throughout the entire duration of the course.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all students, guest lecturers, and coordinators who have contributed to the design and management of the course. The authors would also like to thank the staff at Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health for their support.

Funding

There is no funder for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors confirm that the manuscript is original work of authors which has not been previously published or under review with another journal. The authors confirm that all research meets legal and ethical guidelines and that all possible conflict of interest for this paper has been explicitly stated even if there is none. The authors are not using third-party material that requires formal permission.

References

Allen, D. D., Penn, M. A., & Nora, L. M. (2006). Interdisciplinary healthcare education: Fact or fiction? American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 70(2), 39. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1636929/

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York, NY: Longman.

Friedow, A. J., Blankenship, E. E., Green, J. L., & Stroup, W. W. (2012). Learning interdisciplinary pedagogies. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 12(3), 405-424. https://doi.org/10.1215/15314200-1625235

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Piaget, J. (1971). Psychology and epistemology: Towards a theory of knowledge. New York, NY: Grossman.

*Julian Azfar

Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health,

National University of Singapore,

12 Science Drive 2, #10-01,

Singapore 117549

Email: ephjam@nus.edu.sg

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 1-4

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/GP1084

Colm Bergin1 & Mary Horgan2,3

1School of Medicine Trinity College Dublin, Ireland; 2Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, Ireland; 3School of Medicine, University College Cork, Ireland

Abstract

Medical education and training has evolved over the centuries. Ireland has a long history of leading on aspects of training that remain relevant today, focussing on the apprenticeship model coupled with a robust modern medical education framework. The practice of medicine is changing rapidly driven by expanding knowledge, advances in technology and use of artificial intelligence, demographic shifts and the expectations of patients and society. Medical training and education need to adapt to ensure that our current knowledge and future medical workforce is prepared for modern-day patient-centric practice. Ireland has emerged as a world leader in medical device technology, pharmaceutical research and development and social media technology support which offer the opportunity for the future of medical training. Knowledge, emotional intelligence, critical thinking, compassion, resilience and leadership are key attributes to which we as a profession aspire. There is an opportunity to leverage Ireland’s global position in technology and finance to train our modern-day medical workforce whilst retaining the attributes of the compassionate practice of the art of medicine. This paper explores the past, present and future of medical education and training in Ireland.

Practice Highlights

- Ireland has a history of leading in medical education.

- Training focusses on the blended apprenticeship model.

- Ireland is now a world leader in medical device technology, pharmaceutical research and social media technology.

- Agility, diversity and flexibility are embedded in the modern day medical training model.

- Compassion and communication remain pivotal to the practice of medicine.

I. INTRODUCTION

Ireland is a small island on the westerly fringe of Europe separated from Great Britain by the Irish Sea and with a population size similar to Singapore. Although Ireland is a small nation, its global impact is large due to the high value we, as a nation, put in educating our population. Ireland now ranks fourth in the world in the UN’s Human Development Index, a widely accepted measure of living conditions or quality of life across the globe. Ireland is ranked second to Singapore in reading performance in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2019) rankings. The enrolment of 17-year-olds in Ireland’s secondary education system is 99.3%, with well over the OECD average continuing on to tertiary level education. Ireland is a hub for many major pharmaceutical, medical devices and technology companies which has allowed growth in research. Partnerships between industry and Irish universities facilitate innovation and research in the medical and life sciences sectors. There are six medical schools in the Republic of Ireland, one of which dates from the 17th century and four from the 19th century. Ireland is justly proud of the history and quality of its medical education. This article outlines the past, present and future of undergraduate and postgraduate education in Ireland.

II. THE PAST

Ireland has a long history of being at the forefront of medical education. Many of the Presidents of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI), which was founded in 1654, have played eminent roles in innovation in medical education since the 17th century (Coakley, 1992). Medical education started in Ireland with the appointment of John Stearne as the first professor of medicine at Trinity College in the 1650s. The School of Anatomy in Trinity College did not open until 1711; however, following its opening, the medical school flourished.

Worldwide, doctors and medical students associate the name of Robert Graves with the disease of the thyroid gland however few are aware of the key role he played in the development of bedside teaching. During the early 19th century, Graves introduced two elements of radical change in medical education: the distribution of the care of patients to senior medical students and the changing of teaching from the lecture room to the bedside of the patient. These fundamental changes in medical education developed the skill of observation and ensured that errors in clinical judgement were corrected on the spot (Coakley, 1992). Grave’s method of teaching was adopted in the English-speaking world and continues to this day. Graves constantly exhorted students to spend time on the wards gaining practical experience. Graves appreciated the importance of what is now called continuing professional development by stating that “if a teacher is to maintain the credibility of his students he must keep up with modern advances” (Coakley, 1992, p. 91).

While Graves and his colleague Dr Stokes (the condition Cheyne Stokes respiration bears his name) “were not the first to make use of beside teaching, they did so consistently and so successfully that it was adopted by clinical teachers elsewhere” (p. 94) according to Professor Daniel Reisman writing in the Medical History of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1921 (Coakley, 1992).

In the late 19th century, the first generation of women doctors found the Irish medical hierarchy to be unusually open-minded with regard to the question of women’s admission in contrast to the policy in Great Britain. The Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (previously known as King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland) was the first institution in the British Isles to admit women who had taken their studies abroad to their licentiate examinations in 1877 thereby allowing the first registration of female doctors in Great Britain and Ireland. Sophia Jex Blake, a leading campaigner for women’s admission to the medical profession from the 1860s, remarked that this decision was “the turning point” in the societal shift to gender equality in medicine as a profession.

III. THE PRESENT

A. Undergraduate Medical Education

Medical education in Ireland is provided by six medical schools. In 2006, the Irish government commissioned a report “Medical Education in Ireland: A New Direction”, the Fottrell report (Working Group on Undergraduate Medical Education and Training, 2006), which addressed core issues such as funding, selection criteria for medical school entry and intake numbers, curriculum reform, clinical training and oversight of undergraduate education. The implementation of the report resulted in, 1) expanded and new access routes to medical school with the addition of Graduate Entry Medical programmes in four of the schools, 2) curricular reform with outcomes linked to objectives, content, delivery methodologies, and assessment thereby expanding the methods by which education is delivered in line with international standards, 3) increased funding for faculty and infrastructure, 4) expansion of teaching to primary care facilities and, 5) accreditation of all clinical sites in partnership with Ireland’s national health service, the Health Service Executive (HSE).

Admission to medical school for Irish students is highly competitive, with ten applicants for each place. For school leavers, places are awarded on the basis of a combination of marks achieved in their high school exit examination and the recently introduced Health Professions’ Aptitude Test Ireland. Graduate entry students must achieve at a minimum upper second class honours primary degree and are then admitted on the basis of performance in the Graduate Medical School Admissions Test. Places at Irish medical schools are highly sought after by international students because of the international reputation for high-quality medical education in Ireland, and the safe, welcoming nature of the country. Students apply through international agents and are offered places based on academic performance, interviews and personal statements.

The Medical Council of Ireland regulates undergraduate medical education in accordance with the World Federation for Medical Education Standards. Irish medical schools have long been recognised for their strengths in providing an excellent grounding in foundational sciences, coupled with high-quality clinical teaching, experiential training and an emphasis on professionalism. Recent decades have seen innovation in the areas of inter-professional learning and team-based practice, research and innovation skills, the humanities in medical education, simulation and other forms of technology-enhanced learning. The universities have established academic units specifically dedicated to medical education and offer masters level qualifications in medical education.

Undergraduate medical education in Ireland shares many challenges with other jurisdictions including the continued provision of high-quality clinical learning environments for placements, supporting students’ health and wellbeing, and ensuring that graduates are well prepared for modern-day practice. Irish medical schools have retained the formal observed examination of bedside practice and communication as a significant component of the final year medical examinations.

International partnerships to support medical student exchange programmes are underpinned by memoranda of understanding. These facilitate high-quality research and clinical electives to enhance the student experience and prepare them for future practice in differing healthcare settings.

B. Postgraduate Medical Education

The governance of postgraduate education and training is under the remit of the Royal Colleges which are funded by the HSE to provide training on clinical sites. There are 13 postgraduate training bodies across all domains of practice. The RCPI is the largest training body with 1500 trainees in the specialities of medicine: paediatrics, obstetrics and pathology. Following a year’s internship, trainees enter two years of general professional training (residency) followed by a five-year fellowship of speciality training during which many trainees undertake formal research training to the level of MD/PhD. Partnership between the universities and the postgraduate training bodies has led to the establishment of structured training programmes to train academic clinicians such as the Irish Clinical Academic Training Programme.

The tradition of Irish doctors doing part of their training overseas is a well-established practice. Since the 1950s, the well-educated Irish diaspora have emigrated to develop professionally and return to Ireland to contribute their new knowledge and skills to society. Specifically, the Irish healthcare system has benefitted greatly from these medical graduates returning to Ireland bringing not only the expertise of their particular medical speciality but also the benefits gained from the experiences of working in different health systems.

In recent years, the Irish government published two reports on postgraduate medical education and training: “Preparing Ireland’s Doctors to Meet the Health Needs of the 21st Century”, Buttimer report (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Group, 2006) and “Strategic Review of Medical Training and Career Structures”, McCraith report (Department of Health, 2014). These reports address the global challenges of doctor recruitment and retention, emerging healthcare needs of the population and the need for medical training and practice to incorporate use of modern-day technologies and fiscal responsibility and stewardship.

IV. THE FUTURE

There are three key elements to consider in the future planning of medical education and training: the modern-day workforce, the patient and the workplace environment. The increased financial challenge from rising healthcare costs is a central consideration for the future of medical education and training. Medical training needs to provide diversity in who we train and what we train doctors for, flexibility in training and work practice, and agility in how we respond to new challenges. We need models of collaboration with the sharing of learning material across borders, avoiding “reinventing the wheel” in a resource-scarce world.

The modern-day workforce is the most educated of all generations. They embrace technology and look for opportunities to innovate. They want a work-life balance that ensures job satisfaction and avoids burnout. The “one size fits all” model of a doctor needs to be “retired” to allow smart young medical professionals to adapt to the needs of the modern-day work patient and work environment. The future will require doctors to leave their comfort zones and work with other professionals outside healthcare. To achieve this, medical training will need to embrace innovation and entrepreneurship, providing doctors with experiential learning in the disciplines of business, science, engineering and law. Ireland is well-positioned to leverage on experiential learning and internships with global pharmaceutical, medical technology and medical device companies, as most of the world’s major companies are based in the country. Programmes, such as Bioinnovate Ireland, establish teams of doctors, other healthcare professionals, engineers and business school graduates who partner to identify innovative solutions to healthcare delivery. Health Innovation Hub Ireland brings innovation in and out of the health service and is a partnership between the medical schools and teaching hospitals and is funded by the Irish government through Enterprise Ireland. Initiatives such as this offer a new funding structure through which these companies sponsor applicants. The output from such partnerships will ensure that doctors become skilled innovators who can provide leadership in tackling global health issues such as disparity and inequality in healthcare access and healthcare provision, embedded in a sustainable financial model.

The new generation of doctors wants the option to practice differently. Modern-day society and individuals have increasing expectations of the healthcare system and their doctors. Doctors need to be effective in managing these expectations through knowledge exchange and communication. The modern-day practice is impacted by external influences, some predictable such as demographic shifts and workforce and resource scarcity; others unpredictable, such as new technological and therapeutic breakthroughs and shifts in global economic power. What is certain is a finite healthcare budget, so cost-consciousness must be built into our training programmes. What is uncertain is how we can deal with the unpredicted nature of quality healthcare provision.

Notes on Contributors

Professor Colm Bergin is a consultant physician in Infectious Diseases at St James’ Hospital and a clinical professor of medicine at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. He is Director of Training Site accreditation RCPI and Censor in RCPI. He is the former director of Wellcome HRB Clinical Research Facility, Trinity College Dublin

Professor Mary Horgan is the president of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland and former Dean of the School of Medicine, University College Cork. She is a consultant physician in Infectious Diseases at Cork and has served on numerous government-appointed boards and Governor of University Board.

Acknowledgements

Professor Tim O’Brien National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG), Dr Carmel Malone NUIG, Professor Michael Keane University College Dublin (UCD), Professor Paula O’Leary University College Cork (UCC), Dr Deirdre Bennett UCC and Dr Roisin Craven Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (RCPI).

Funding

There is no funding involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Coakley, D. (1992). Irish masters of medicine. Dublin, Ireland: Town House.

Department of Health. (2014). Strategic review of medical training and career structure: Report on medical career structures and pathways following completion of specialist training. Retrieved from https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/317460

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2019). Population [Indicator]. https://doi.org/10.1787/d434f82b-en

Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Group. (2006). Preparing Ireland’s doctors to meet the health needs of the 21st century. Retrieved from https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/42920

Working Group on Undergraduate Medical Education and Training. (2006). Medical education in Ireland: A new direction. Retrieved from https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/43350

*Mary Horgan

Royal College of Physicians of Ireland,

19 South Frederick Street, Dublin 2, Ireland

Tel: +35 32149 01596

Email: m.horgan@ucc.ie

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 51-53

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/PV2171

Heng-Wai Yuen1,2,3 & Abhilash Balakrishnan2,3,4

1Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, Changi General Hospital, Singapore; 2Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 3National University of Singapore, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Singapore; 4Department of Otolaryngology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

I. INTRODUCTION

Big data (BD) involves aggregating and melding large and heterogeneous datasets, allowing searches and cross-referencing, and deriving insights and meaning from them. It has tremendous potential for application in medical education (ME) where the massive amounts of data that are generated and collected about learners, their learning, and the organisation of their learning can be analysed and interpreted to provide meaning and insights into various aspects of ME. This article briefly introduces BD, potential areas of application, and highlights the pitfalls and challenges surrounding the use of BD in ME (BDME) from the authors’ perspectives.

II. BIG DATA IN MEDICAL EDUCATION (BDME)

The concept of BD has its origins in commercial industries, and also academic and technical disciplines (e.g., astronomy and genomics) where enormous amounts of complex data and information are routinely collected, managed and analysed (Ellaway, Pusic, Galbraith, & Cameron, 2014; Schneeweiss, 2014). This information possesses characteristics denoted by the four Vs: high Volume, Variety, Velocity, and Veracity (validity); conventional database software tools are unable to fully capture, store, process, or analyse them (Ellaway et al., 2014). BD is relatively new in clinical medicine and applying BDME has been slow and limited (Cook, Andriole, Durning, Roberts, & Triola, 2010; Ellaway et al., 2014) Nonetheless, in the last few years, there are increased efforts to apply BD to ME (Chahine et al., 2018; Ellaway et al., 2014). To this end, ME is well suited for BD application as a massive volume of complex data is generated and collected constantly from different programs and educational institutions, and from multiple sources, both structured and unstructured: e.g., electronic medical records, assessment results and test scores, evaluation and feedback information, as well as curriculum and program evaluation (Chahine, et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010). By harnessing the power of BDME, information and data can be aggregated, integrated, and analysed, then interpreted and acted on if necessary (Ellaway et al., 2014; Schneeweiss, 2014).

III. POTENTIAL APPLICATIONS OF BDME

The potential of BDME includes both practical (e.g., program and curriculum assessment and evaluation) and research applications. Depending on the purpose and/or research question, the data mining may be on a broad, systems-level or a personalised small-scale basis. BDME application organises and crystallises the data to enable a better understanding of and insight into what happened, and what is currently happening. This may occur through various different ways of analyses including prospective longitudinal analysis, trend discovery, pattern recognition and predictive analytics. Hence, predictions or extrapolations might be made in regards to what may yet happen in curriculum, programs and educational practices (Chahine et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010; Ellaway et al., 2014).

For instance, BDME can facilitate decision-making in undergraduate ME, e.g., entry selection of medical students, or readiness of a medical student to graduate. In postgraduate ME, BDME can provide insights into data on learners’ experience and exposure, feedback information, as well as assessment data within and across programs (Chahine et al., 2018; Ellaway et al., 2014). This allows personalised feedback and individualised learning plans (Chahine et al., 2018), and facilitates the implementation of entrustable professional activities (EPA). Learning gaps and teaching lapses can also be identified to support improvement or changes to certain practices or contents. Applying BDME on these educational and other data (such as demographics, admission criteria or educational practices) in a longitudinal and cross-sectional manner allows benchmarking and accountability across different cohorts, programs, and institutions. This is vital for continuous quality assurance and improvement of ME practices (Chahine et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010; Ellaway et al., 2014), or for evaluation of upstream policies (Chahine et al., 2018; Schneeweiss, 2014). These same processes can also be performed across countries to inform ME from international or cross-cultural perspectives.

Another potential application of BDME is to investigate the (hitherto assumed) link between ME and patient care. Drawing on combined data from educational and clinical information repositories (e.g., correlating patient outcomes from hospital and clinic health information systems with different models of educations within and across institutions), one would be able to evaluate if, and to what extent, educational practices translate into improved health care outcomes for patient and society (Chahine et al., 2018). One example is the Jefferson Longitudinal Study of Medical Education (Callahan, Hojat, Veloski, Erdmann, & Gonnella, 2010) whereby data on 8000 students who were tracked over 40 years showed that MCAT examination performance is a valid predictor of medical school and residency performance. This and other studies confirmed the feasibility and utility of applying BD to inform current medical educational practices, and to bridge the gap between pedagogical theory and practice. Further, by enabling a longitudinal view of physicians’ progression and development through their education, and the career choices made, BDME can provide information and evidence to facilitate recommendations for important strategic policies and decisions, e.g., manpower planning or speciality development. These are subjects of interest for policy-makers, regulatory authorities, medical educators and researchers.

IV. POTENTIAL OBSTACLES AND PITFALLS

Whilst there are many potential fruitful applications of BDME, some challenges and issues must be critically addressed before the widespread adoption of BD into mainstream ME practice.

Data fragmentation, so common in healthcare systems, is a major obstacle to the widespread use of BDME (Ellaway et al., 2014; Schneeweiss, 2014). For a start, electronic health or medical records (EMR) are frequently incompatible and heterogeneous across hospital systems that store the data (Chahine et al., 2018; Ellaway et al., 2014). Practice standards and vocabulary are also not standardised. Also, healthcare systems are not required (or willing) to exchange and share data with each other. In addition, organisational policies regarding security and confidentiality limit data accessibility (Chahine et al., 2018; Ellaway et al., 2014). Further, there are ethical and medicolegal considerations. For instance, most of the patient data captured on EMR was not originally intended for education purposes, and does not include informed consent in this respect. Even if the data can be anonymised with identifiers removed, questions remain on what data is collected, how the data is stored and protected, how it is used and shared – by whom, and with whom. These issues extend to ME data too; confidentiality issues and access restrictions to data collected on learners, programs and institutions can limit the quality, analysis and value of BDME.

Hence, government and health authorities, EMR companies, hospitals and training institutions must cooperate to improve medical data and information systems, and strengthen data exchange and integration across organisations (Chahine et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010; Ellaway et al., 2014). Appropriate legislations or policies may be necessary. Investments in infrastructure, technologies and expertise to manage and protect data from different sources are also needed. The infrastructure and technological expertise (for collection, storage, processing and analysis) could be centralised in a ‘data warehouse’ – different institutions become data providers to this ‘central’ BD collective (Cook et al., 2010; Ellaway et al., 2014). It is likely that external partners (e.g., data science, informatics) will be involved to facilitate and optimise the use of BD. Under these circumstances, the governance, ownership of, and access to data are important issues to consider.

In using BDME to correlate training and clinical care outcomes, the challenge is being able to accurately link a learner’s (or a cohort of learners’) education and training with patient-level or system-level clinical outcomes (Chahine et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010). Given that multiple healthcare providers (students, residents, practicing physicians) may be involved in the care of a particular patient, innovative data analytical algorithms or techniques will be necessary in order to identify or ‘tag’ different aspects of clinical care or patient encounters, and accurately attribute these to specific providers over prolonged periods of time, and across institutional, clinical and educational boundaries (Chahine et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010). If successful, this will provide unprecedented potential for performance assessment and evaluation.

The application of BDME also has inherent limitations and fallibility (Chahine et al., 2018; Ellaway et al., 2014). The interpretations and conclusions (and the subsequent decisions and actions) based on BDME must be made with extreme caution. The standards and rigours of academic and scientific research must be applied and met – in the collection methods, precision, representativeness of data. There is intrinsic bias in BD due to the fact that information that cannot (or simply are not) be captured may be undervalued or ignored. Predicting trends and judging current and future potential and success of individuals or programs must similarly be tempered with caution (Chahine et al., 2018; Cook et al., 2010). Major decisions (especially summative) must be based on time-honoured, empirically proven principles: multiple data points, from multiple sources (triangulation), at different time points (reiterative), and after considering the dynamic nature of learning and education in reality.

There are real risks to the individuals and systems if BDME is used out of context, or for unintended purposes. For instance, should BDME be used to alter a learner’s (or a group of learners’) career path or choice? Should we judge learners based on ‘normal’ patterns of learner behaviour derived from BDME? Also, from the faculty’s perspective, it is tempting to use only those educational interventions that were ‘shown to work’ by BDME, at the expense of all others.

This article is not intended to propose solutions to the many issues surrounding the use of BDME. The permeation of BD into ME appears inexorable. It is time for the ME community to take the lead to critically appraise and shape the conversation surrounding BDME, so as to set the agenda and direction for the best use of BDME.

Notes on Contributors

Heng-Wai Yuen is an adjunct Associate Professor with the Duke-NUS Medical School and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD). He is the Director of Otology and Hearing Implants in the Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, and the Deputy Director of Undergraduate Medical Education at Changi General Hospital.

Abhilash Balakrishnan is an adjunct Associate Professor with the Duke-NUS Medical School and Clinical Associate Professor with the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore. He is also the Deputy Head of Department (Education) in the Department of Otolaryngology at Singapore General Hospital.

Funding

The authors declare no funding is involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Callahan, C. A., Hojat, M., Veloski, J., Erdmann, J. B., & Gonnella, J. S. (2010). The predictive validity of three versions of the MCAT in relation to performance in medical school, residency, and licensing examinations: A longitudinal study of 36 classes of Jefferson Medical College. Academic Medicine, 85(6), 980-987. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cece3d

Chahine, S., Kulasegaram, K., Wright, S., Monteiro, S., Grierson, L. E., Barber, C., … Touchie, C. (2018). A call to investigate the relationship between education and health outcomes using big data. Academic Medicine, 93(6), 829-832. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002217

Cook, D. A., Andriole, D. A., Durning, S. J., Roberts, N. K., & Triola, M. M. (2010). Longitudinal research databases in medical education: Facilitating the study of educational outcomes over time and across institutions. Academic Medicine, 85(8), 1340-1346. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e5c050

Ellaway, R. H., Pusic, M. V., Galbraith, R. M., & Cameron, T. (2014). Developing the role of big data and analytics in health professional education. Medical Teacher, 36(3), 216-222. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.874553

Schneeweiss, S. (2014). Learning from big health care data. The New England Journal of Medicine, 370(23), 2161-2163. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1401111

*Heng-Wai Yuen

Changi General Hospital,

2 Simei Street 3, Singapore 539889

Tel: +65 69366259

Email: yuen.heng.wai@singhealth.com.sg

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 48-50

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/PV2176

Neel Sharma1, Mads S. Bergholt2, Rosalia Moreddu3 & Ali K. Yetisen3

1Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham, United Kingdom; 2Centre for Craniofacial and Regenerative Biology, Faculty of Dentistry, Oral & Craniofacial Sciences, King’s College London, United Kingdom; 3Department of Chemical Engineering, Imperial College London, United Kingdom

I. INTRODUCTION

Medicine historically relied on astute history and examination skills. As technology was lacking, ward rounds focused on debate and discussion of diagnoses and possible differential diagnoses based on the history and physical examination. The technology movement into healthcare was never truly predicted. With its occurrence, came the ability to scan a patient from top to toe via computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Technology now serves as our main diagnostic tool (Patel, 2013).

‘When did the patient have their scan? Shall we repeat it? Maybe we are missing a subtle cancer?’ These are now common questions.

For those that enter medicine, we do so on the basis of the intellectual challenge, the desire to piece together a patient’s symptoms and examination findings and formulate a diagnosis. However, we have now become technicians. Patients are imaged and labelled depending on what the scan tells us. Has our critical thinking now gone (Hall, 2019)?

We urgently need to reinject the thinking into healthcare. Otherwise, retention and recruitment into the medical field will diminish. How can we achieve this? Technologies certainly will not die and patients want them. Hence, we envisage a change in the way doctors are trained. A system where future doctors not only gain clinical knowledge but engineering expertise. By developing a training system whereby engineering colleagues can provide medics an understanding of device and diagnostic development, we will not only be able to accurately diagnose and manage patients but also be able to keep the thinking alive. As clinicians can recognise the limitations in how patients are managed, they can solve these limitations once armed with engineering know-how.

II. METHODS

As the authors of this piece, we have launched the first global clinician engineering platform for medical undergraduates, the clinician engineer hub (www.clinicianengineer.com). The hub is led by one founding clinician NS and two founding engineers MSB and AKY. All members have global experience in their respective fields including internal medicine, gastroenterology, biomedical imaging and biosensors. Next came the decision to recruit an international advisory board, comprising senior experts and mid-level career individuals. Recognising the fact that medical students undertake sabbaticals abroad, it was essential to ensure an international angle. The focus of the first programme was on biomedical optics for early cancer diagnosis and wearable sensors for real-time health monitoring. The focus of the engineering content was based on consensus among the founders and advisory board with the decision to review the theme of the programme on a biannual basis. The programme took place over a two-week period. The first week involved clinical observation to understand the clinical problem and what potential limitations exist in terms of diagnosis and treatment. This involved exposure to patients in an outpatient setting and in the ward. The second week focused on theoretical aspects of engineering and device development. Additionally, it involved lectures and hands-on practical activities. Each learner gained appropriate credit for full participation in the programme with the opportunity to provide feedback on how to enhance the learning experience.

III. DISCUSSION

As the programme builds, our aim is to next integrate engineering training during medical school which can be done in a variety of ways. It could, for example, commence as an elective. Alternatively, of more value, during each attached clinical rotation, be it gastroenterology, cardiology, or respiratory medicine, there could be dedicated teaching time allied to limitations in current diagnostic practice and management strategies with time spent appreciating current engineering strategies and solutions, seamlessly integrated into the curricula (Tables 1 and 2). This way, both disciplines can be learnt simultaneously without prolongation of training time.

The clinician engineer training scheme can also be integrated into allied health care curricula. Globally, we are seeing healthcare being delivered by nurse specialists, physician assistants, and specialist prescribers. Nurse specialists, for example, exist in the field of heart failure management, diabetes, and asthma. Physician assistants play a significant role in the history and examination of patients as well as diagnosis forming. As these individuals enter their respective university programmes, their exposure to patient problems can also be of benefit to developing new diagnostic and treatment methods, alongside fellow clinicians, through an integrated engineering syllabus.

|

Cardiology |

Gastroenterology |

|

AM: Ward round |

AM: Ward round |

|

PM: Clinic |

PM: Endoscopy observation |

Table 1. Current teaching model during medical school

|

Cardiology |

Gastroenterology |

|

AM: Ward round/ Clinic (alternating) |

AM: Ward round/ Endoscopy (alternating) |

|

PM: Teaching on diagnostic and treatment limitations in cardiology with exposure to novel engineering-based solutions (e.g., wearable sensor construction for arrhythmia detection) |

PM: Teaching on diagnostic limitations in gastroenterology (e.g., limitations with current endoscopic equipment for cancer detection and possible solutions such as spectroscopy) |

Table 2. The proposed timetable for clinician engineering teaching at medical school

IV. CONCLUSION

Innovation in medical education is urgently needed. For decades, we have spent time and resources appreciating the most appropriate teaching strategy or way to assess our learners. We have now reached saturation in this regard. There is no one optimum way to teach a learner and no single optimum assessment method. What we now need is a stronger focus on healthcare deficiencies at a time where healthcare provision remains heavily invested in technology. Critics may highlight concerns allied to faculty resources, training of faculty as well as accreditation. However, it is our duty as educators to ensure our patients benefit from future doctors who have been trained in accordance with how healthcare is evolving. With expert clinicians and engineers already highly trained and guiding such programmes, full accreditation can be gained. The future is now not just clinical care but clinician engineering.

Notes on Contributors

NS is the founder of the clinician engineer hub and a clinician academic in gastroenterology.

MSB is a co-founder of the clinician engineer hub and lecturer in biophotonics.

AKY is a co-founder of the clinician engineer hub and senior lecturer in chemical engineering.

RM is a PhD candidate in biomedical engineering and instructor for the clinician engineer hub.

NS, MSB, AKY, and RM contributed to the article equally and agreed on the final version for submission.

Funding

The authors declare no funding is involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Hall, H. (2019, January 15). Critical thinking in medicine. Science-Based Medicine. Retrieved from https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/critical-thinking-in-medicine

Patel, K. (2013). Is clinical examination dead? BMJ, 346, f3442. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3442

*Neel Sharma

Department of Gastroenterology,

Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham,

Mindelsohn Way, B15 2TH

Tel: 0121 371 2000

Email: n.sharma.1@bham.ac.uk

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 45-47

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/PV1085

Chi-Wan Lai

Koo Foundation Sun Yat-Sen Cancer Center, Taipei, Taiwan

I. INTRODUCTION

Most medical education programmes in Taiwan accept students upon high school graduation. Medical education used to consist of seven years with the last year being an internship. Since 2013, medical students have graduated at the end of six years, and the internship has been moved to a postgraduate year. In both formats, students have been offered medical humanities courses in the “pre-med” phase, i.e. the first two years of medical school. From the third year onward, however, students rarely have exposure to subjects related to humanism, other than courses on medical ethics and some problem-based learning case discussions. Moreover, medical students have had very little exposure to humanities in high school. Such limited exposure to humanities during medical school can have detrimental effects on cultivating humanistic physicians in Taiwan.

It is known that the majority of medical schools in the U.S. are post-baccalaureate system, i.e. most of the medical students have already had exposure to humanities courses during undergraduate years. Yet research shows that medical students in the U.S. have problems with empathy decline as they advance through medical school (Neumann et al., 2011). The Arnold P. Gold Foundation has been advocating for infusing the human connection into healthcare, and Plant, Barone, Serwint, & Butani (2015) articulated very well the need to take humanism back to the bedside. Lacking these efforts, the empathy decline among medical students in Taiwan could conceivably be even more serious than in the U.S.

This paper advocates for the importance of instilling humanism at the bedside during clinical rotations to serve as “booster shots” to enhance the medical humanities learned by students in the pre-med phase.

II. MY PERSONAL EXPERIENCES IN LEARNING AND TEACHING AT THE BEDSIDE

Following my graduation from medical school at National Taiwan University School of Medicine in 1969, I completed a four-year residency in the Neurology & Psychiatry Department at Taiwan Medical University Hospital (1970-1974) and did an attending year before I went to the University of Minnesota to start another residency program in Neurology (1975-1978). In Minnesota, I was deeply impressed by the bedside teaching of my respected mentor, Dr. A. B. Baker, the chairman of the Neurology Department. I vividly remember one unforgettable incident – before he did a “straight leg raising test” (Swartz, 2014) on a female patient suffering from sciatica, he first asked for a towel to cover the area between the patient’s legs before raising her leg to test the possibility of sciatic nerve entrapment. He clearly demonstrated sensitivity to the patient’s potential feeling of embarrassment caused by performing such a test while surrounded by students and residents. Through several of these “enlightening moments” at the bedside, he demonstrated his famous quote: “Students learn from observing how you do, rather than from what you say.”

Since then, I have continued my interest in bedside teaching while teaching at the University of Kansas Medical Center (1979-1998) and upon my return to Taiwan in 1998.

It is my personal conviction that bedside teaching should include not only medical knowledge and skills but also bedside manner, sympathetic listening and empathetic communication. Such teaching can serve as “booster shots” during clinical years to enhance the humanism that medical students learn in earlier years. For more than a decade, I have been conducting regular bedside teaching in three teaching hospitals for 5th or 6th year medical students at National Yang Ming Medical University, National Taiwan University, and National Cheng-Kung University during their clerkship rotating through neurology.

I would like to present the following two cases to illustrate how to enhance students’ sensitivity to the suffering of others (patients and their families), while also teaching neurological examination techniques, differential diagnoses, and management.

III. CASE 1: A PATIENT WITH MYASTHENIA GRAVIS WHO SUFFERS FROM DIPLOPIA

The diagnosis was delayed by his presenting chief complaints as “dizziness,” for which he visited several ENT doctors, until finally he was referred to neurologists. Students were puzzled by how the patient could “confuse” diplopia (“double vision”) with dizziness. I then demonstrated to students how to self-induce diplopia by stretching out their left arm, with index finger pointed to the sky, and then continue to stare at this finger while trying to apply pressure to their right eyeball with their right hand. This would artificially create different positions of the eyeballs (dysconjugation), resulting in problems with the fusion of two images projected from the retinae to the brain. This caused “double vision” and a dizzy feeling, which was exactly what happened to this patient. Students then appreciated what the patient was suffering and understood why the patient could perceive “double vision” as “dizziness.”

IV. CASE 2: A PATIENT AT THE END-STAGE OF AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS, A DEVASTATING MOTOR NEURON DISEASE THAT HAS NO EFFECTIVE TREATMENT

After the student presented the history of the patient, I reminded students to find out how we could help such a seemingly “medically helpless” patient. After observing severe bulbar symptoms and demonstrating the coexistence of upper and lower motor neuron signs at bedside, I thought it might be a good case to lead the patient into a discussion of serious issues related to end-of-life.

So I posed a question – “What do you worry about the most?” – trying to lead the patient into a discussion of whether he would consider accepting emergent intubation followed by long term ventilation when he developed difficulty with breathing. Unexpectedly, the patient responded, “What I worry about the most is my daughters’ education.” He then went on to share with us his story of how his lack of formal education due to poverty led him to the life-long misery of humiliation at work. Consequently, he has tried to save as much money as possible for his two daughters’ college education. Unfortunately, his financial status had been seriously compromised by his loss of job and increasing medical expenses since he became ill, at a time when his two daughters would soon graduate from high school.

After we left the patient and started discussing the patient’s neurological findings, one student reminded us that we had not discussed how to help this patient. She went on to share with us her thoughts: she would like to see the patient’s daughters, discuss with them whether they themselves were interested in going to college, and if so, she would urge them to speak to their father about their desire to work in the daytime and to attend college through evening school.

We were all impressed by this student’s thoughtful proposal, and I went on to praise her, saying that she had beautifully illustrated the truth of the following statement: “Although there is nothing more that can be done for the body, this does not mean that there is nothing more that can be done for the sick person” (Cassell, 2004).

V. GENERAL DISCUSSION OF HOW I CONDUCT BEDSIDE TEACHING

At the end of my bedside teaching, I usually ask students to share what they have learned. Students tend to recall cognitive learning, i.e. medical knowledge of diagnosis and treatment as well as clinical skills in neurological exam. Then under prompting, they begin to share their observations of behavioral/affective aspects and express their empathy towards the suffering of patients and their families. Some of them voice their appreciation for bedside manner and communication skills demonstrated by the medical team. At the end, I have consistently tried to raise their sensitivity and draw attention to the patient’s suffering. Lately, I like to share with students the joy of reading Dr. Charon’s succinct article, “To See the Suffering,” in which she writes, “To see the suffering might be what the humanities in medicine are for, and that those who become capable of seeing the suffering around them in medical practice both experience the cost of countenancing the full burden of illness and death and, simultaneously, comprehend with clarity the worth of this thing, this life.” (Charon, 2017)

VI. MY PERSONAL PLEA FOR THE INTEGRATION OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND HUMANITIES IN MEDICAL EDUCATION PROGRAM

Attention to humanistic issues at the bedside demonstrates to students the relevance and application of humanities in individual cases and leads to a deeper appreciation of what they have learned about medical humanities during their pre-med years. Consequently, such bedside teaching can serve as “booster shots” to rekindle students’ interest in the humanistic aspects of patient care. However, it is difficult to expect lasting effects on the attitudes and behaviors of medical trainees unless such teaching can be frequently and widely practiced throughout clinical rotations.

Therefore, I would like to recommend that more attending physicians in teaching hospitals should be encouraged to teach humanism at the bedside. Medical schools should set a high priority for the clinical faculty to help students enhance their sensitivity “to see the suffering” and develop empathy towards patients. If possible, such efforts should be incorporated into faculty development programs for clinical teachers from all clinical departments in teaching hospitals.

Note on Contributor

Chi-Wan Lai, M.D. is the chair professor of medical education, attending physician in the Division of Neurology, Koo Foundation Sun Yat-Sen Cancer Center, Taipei, Taiwan.

Funding

The author declares no funding is involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

Cassell, E. J. (2004). The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine (2nd ed., p. 118). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Charon, R. (2017). To see the suffering. Academic Medicine, 92(12), 1668-1670. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001989

Neumann, M., Edelhäuser, F., Tauschel, D., Fischer, M. R., Wirtz, M., Woopen, C., … Scheffer C. (2011). Empathy decline and its reasons: A systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Academic Medicine, 86(8), 996-1009. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615

Plant, J., Barone, M. A., Serwint, J. R., & Butani, L. (2015). Taking humanism back to the bedside. Pediatrics, 136(5), 828-830. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3042

Swartz, M. H. (2014). Textbook of physical diagnosis: History and Examination (7th ed., p. 564). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

*Lai Chi-Wan

125 Lih-Der Road,

Pei-Tou District, Taipei, Taiwan

Telephone: +886 2 2897-0011

Email address: chiwanlai@gmail.com

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 57-58

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/LE2221

Muhammad Raihan Jumat

Office of Education, Duke-NUS Medical School

I read with great interest Samarasekera and Gwee’s article in TAPS (January, 2020) entitled: “Grit in healthcare education practice”. The authors cited Duckworth’s seminal studies on grit and its strong correlation with success. The authors suggested that grit be used to select for medical students and for healthcare systems to adopt organisational grit. I applaud the authors’ call for implementing organisational grit in healthcare. This is a step forward in working out the multiple issues plaguing healthcare. Interestingly, the call to implement organisational grit might not make it necessary to select for grit upon medical school admission.

Duckworth had posited that the mere assembly of gritty individuals might not necessarily create a gritty organisation (Duckworth, 2016). Students who test as gritty upon admission might be gritty in a different context than that of a medical school. Medical school has its own specific set of challenges which are not shared in many other pre-medical school experience. Hence, students who type as gritty on a medical school entry exam might not remain gritty in medical school.

Grit needs to be developed as a team within an organisation with a shared goal (Duckworth, 2016; Lee & Duckworth, 2018). This development starts with assembling a group of individuals with similar interests. These individuals are then encouraged to work together with chances to carry out deliberate practice and constant reminders of their shared purpose. This group should be even encouraged to fail and learn from those failures. This group will then develop grit as a unit (Duckworth, 2016).

Creating an environment which is demanding yet nurturing is key in promoting grit (Lee & Duckworth, 2018). Team-based or problem-based learning provides a conducive setting for such an environment to thrive in medical school. Students are grouped in teams and are faced with demanding challenges which would force them to work together over an extended period of time. These students are allowed to fail and learn from their mistakes. Over time, the team develops grit.

The formation of a culture which promotes and breeds grit within an organisation would be a stronger force to withstand the demanding challenges of healthcare than just a selection of gritty individuals. Structural changes in healthcare to allow for organisational grit to take root should be undertaken. Increased reports of physician burnout necessitate that healthcare workers be given support. Organisational grit would give healthcare workers the support they require.

Note on Contributor

Muhammad Raihan Jumat, PhD, is an Education Fellow in the Office of Educaiton at Duke-NUS Medical School. The author conceived the idea and wrote this letter.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Professors Scott Compton and Sandy Cook for their advice and encouragement in writing this letter.

Funding

No funding was involved in this letter.

Declaration of Interest

The author does not have any competing interests.

References

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance (First Scribner hardcover ed.). New York, NY: Scribner.

Lee, T. H. & Duckworth, A. L. (2018). Organizational grit. Retrieved from Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2018/09/organizationalgrit

*Muhammad Raihan Jumat

Office of Education,

Duke-NUS Medical School,

8 College Road,

Singapore 169857

Tel: +6 56516 4771

E-mail: raihan.jumat@duke-nus.edu.sg

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 41-44

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/SC2134

Sok Mui May Lim1,2, Zi An Galvyn Goh2 & Bhing Leet Tan1

1Health and Social Sciences Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD), Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore

Abstract

The use of standardised patients has become integral in the contemporary healthcare and medical education sector, with ongoing discussion on exploring ways to improve existing standardised patient programs. One potentially untapped group in society that may contribute to such programs are persons with disabilities. Persons with disabilities have journeyed through the healthcare system, from injury to post-rehabilitation, and can provide inputs based on their experiences beyond their conditions. This paper draws on our experiences gained from a two-phase experiential learning research project that involved occupational therapy students learning from persons with disabilities. This paper aims to provide eight highly feasible, systematic tips to involve persons with disabilities as standardised patients for assessments and practical lessons. We highlight the importance of considering persons with disabilities when they are in their role of standardised patients as paid co-workers rather than volunteers or patients. This partnership between persons with disabilities and educators should be viewed as a reciprocally beneficial one whereby the university and the disability community learn from one another.

Keywords: Standardised Patients, Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), Persons with Disabilities, Inclusion, Role-play, Script, Practical Lessons

I. INTRODUCTION

The use of standardised patients (SPs) has become integral to the contemporary healthcare and medical education sector. While an SP is commonly defined as a person trained to portray a scenario, an SP can also be an actual patient using his or her own history and physical exam findings (Kowitlawakul, Chow, Salam, & Ignacio, 2015). Presently, persons with disability (PWDs) have participated in SP programs, albeit less frequently and on a smaller scale (Long-Bellil et al., 2011; Minihan et al., 2004; Wells, Byron, McMullen, & Birchall, 2002). SPs with disabilities have also been used in Singapore hospitals, but mainly as patients to be examined for their own medical conditions. PWDs have a lot to offer in clinical education beyond sharing about their conditions.

A. Why Incorporate Persons with Disabilities into SP Programs?

There are many benefits in involving PWDs in SP programs. PWDs may be able to impart knowledge that ‘goes beyond the textbook’, due to their experiences of receiving services from various healthcare professionals – from the time the disability occurred to the post-rehabilitation phase of living independently in society. The input given based on their individual experiences would, therefore, be authentic (Wells et al., 2002). Students can get practice working with real PWDs in a safe setting where they can make mistakes and receive feedback before going for their clinical placements and meeting with real patients (Minihan et al., 2004). This can nurture a new generation of healthcare professionals who may be more proficient in treating PWDs, thereby raising the service delivery standard for the entire sector.

B. Perspectives Gained From Previous Experiential Learning Project

This paper is based on our experiences gained from a previous experiential learning research project. PWDs participated in a two-phase experiential learning research project that spanned two years (Lim, Tan, Lim, & Goh, 2018). In phase one, the PWDs acted as community teachers to occupational therapy student groups, interacting with them in the community while performing their daily activities. This paper draws from our experiences in Phase Two of the study, in which a group of PWDs were trained to and worked as SPs in practical classes and Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs). Upon the conclusion of the research project, PWDs continue to be part of the degree programme contributing as community teachers and SPs. The paper aims to provide practical helpful tips in bringing PWDs onboard as SPs.

II. DISCUSSION

A. Tip 1 – Interviewing and Selecting PWDs Who Are Suitable for Acting

PWDs were selected based on six criteria determined by faculty members in the health profession who have prior experience working with SPs. First, the PWD has an interest in healthcare education and wants to work with students for the purpose of educating them as future healthcare professionals. Second, the PWD should have come to terms and accepted their disability. It is very difficult for them to talk about their disability or role-play as a patient when they are still struggling emotionally with their own conditions. Third, the PWD does not have cognitive impairment and is able to understand and remember the script for role-playing. Fourth, he/she must be able to communicate clearly and coherently. Fifth, the PWD should be willing to learn the basics of acting or role-playing. Sixth, he/she must understand the objectives of the training or assessment, such as being impartial to all students and being honest in giving feedback when required.

B. Tip 2 – Training Should Be Conducted in Gradual Phases

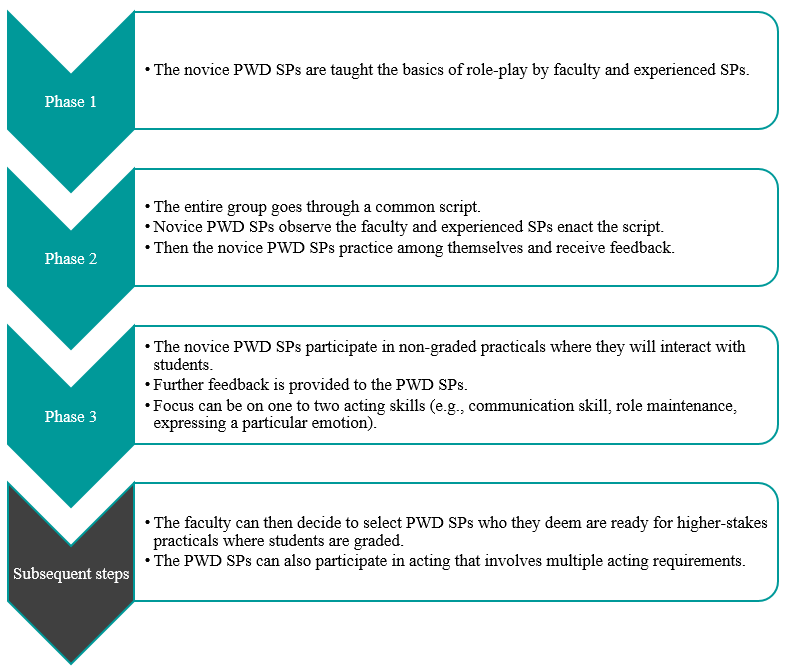

Training PWDs as SPs can be carried out in a gradual phase as outlined in details in Figure 1. In the first phase, novice PWD SPs are taught the basics of role-play by faculty and experienced SPs. In the second phase, the entire group goes through a common script. Novice PWD SPs observe the faculty and experienced SPs enact the script. Then, the novice PWD SPs practice amongst themselves and receive feedback.

After the training, faculty should speak to the PWDs individually to determine if they are comfortable with role-playing and address any queries that they may have. It is only after they attempt the role of an SP that they can personally assess their comfort level and confidence. This can ensure that the PWDs who participate are comfortable with their roles and feel engaged and respected by the institution.

In the third phase, PWD SPs can progress to non-graded practical lessons with students, which are less stressful for both students and PWD SPs. In subsequent phases, the faculty can then decide to select PWD SPs whom they deem are ready for summative assessments such as the OSCE.

C. Tip 3 – Start Novice PWD SPs with Simple and Suitable Scripts

Initial scripts should be simple and should not require complex acting skills. It takes time to gain confidence in memorising required lines, maintaining their roles as well as acting in scenarios which require more expression of emotions. Scripts that involve more sophisticated acting skills (e.g., maintenance of strong emotions) should be reserved for SPs who are experienced and confident with acting. The PWD SPs should be matched to suitable scripts that do not conflict with their disability. For example, a PWD SP who uses a wheelchair cannot be paired with a script that involves walking. The combination of progressing gradually and usage of suitable scripts allows for PWD SPs to refine their skills and ensure that their acting skills do not compromise the students’ learning experience.

D. Tip 4 – Prepare Students Not to Be Surprised By Real Disability

Prior to the interaction session, students should be pre-empted by the faculty that they would be working with PWDs who may have a range of disabilities. This is to prevent unnecessary surprise. In addition, students should be reminded that the disability may or may not be the focus of the scenario, depending on the instruction given to the student. For example, in an OSCE scenario, students may be tasked to explain a medical error or demonstrate a procedural skill instead of addressing the disability of the SP. This pre-empting can be complemented with teaching communication skills geared towards interacting with PWDs.

E. Tip 5 – Checking Accessibility – Within and Outside of the Venue

Ensuring accessibility prior to the session is important. This includes the route from the nearest public transport node (e.g., train station) to the venue. Things to take note of are the availability of ramps and lifts for wheelchair users and the presence of accessible parking lots. In addition, the venue where the lesson or assessment is going to take place needs to be inspected to ensure that the entrances and exits are wide enough for wheelchairs access.

Figure 1. Diagram to outline general recommended steps for training PWD SPs

F. Tip 6 – Pay PWDs at Market Rates and Accord Them Identical Contractual Rights

PWD SPs should be remunerated at market rates that are equal to SPs without disability. They also sign the same SP contract and fulfil the same legal obligations. In performing the role of the SP, they are treated as co-workers of the university, not volunteers or patients. This reflects the principles of equality and diversity, as well as the seriousness of their roles as active members of the healthcare and medical education system. If there are certain risks involved in their interaction with students, such risks should be made clear to the PWD SPs, so they can make an informed decision on accepting the job.

G. Tip 7 – Provide Opportunity for PWDs to Give Feedback

PWDs can be a valuable resource in providing feedback to faculty, scenario developers and other SPs. Similarly, they may be able to give insightful feedback to students. It is important to train the PWD SPs on the methods of providing feedback to students. Given their lived experience, they can provide insight into how real patients would respond and react while suggesting ways for trainee healthcare professionals to respond in a more patient-centred manner.

H. Tip 8 – Reflect and Improve

Carrying out an evaluation with the respective stakeholders, whether they are PWD SPs, faculty, or students, is key to the success of an inclusive SP program. This can also ensure quality assurance of the program. The following are several broad questions which can be considered in the evaluation. Firstly, whether the stakeholder faced any challenges during the session. Secondly, whether the scenarios or scripts worked well for PWD SPs to interact with students. Thirdly, whether there are any other ways that the learning experience can be improved. This can provide rich data for the SP program developers to reflect and improve upon the pedagogy. We have received positive feedback from both students and PWDs in this project.

III. CONCLUSION

It is important to empower PWDs and create a dynamic relationship between them and healthcare professionals/

educators. For an inclusive SP program to be effective, educators must change their own mindset about PWDs. We have to switch the lens from viewing them as patients to co-workers. This partnership should be viewed as a reciprocally beneficial one whereby the university and the disability community learn from one another. Through the process of engagement, both educators and students learn from PWD SPs about knowledge that goes beyond the textbook, and the factors that enhance or diminish the quality of healthcare/medical service delivery from individuals who have experienced going through the healthcare/medical system. With time and with more training institutions engaging PWDs as SPs, this can be a potentially viable employment option for PWDs.

Notes on Contributors

Associate Professor May Lim is the Director of the Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD) at the Singapore Institute of Technology, and a faculty in the Health and Social Sciences Cluster teaching occupational therapy.

At the time when this work was done, Mr Goh Zi An Galvyn was a research assistant in the Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD) at the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Associate Professor Tan Bhing Leet is the Deputy Cluster Director (Applied Learning) of the Health and Social Sciences Cluster, and Programme Director of the Bachelor of Science in Occupational Therapy degree programme at the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Singapore Institute of Technology Institutional Review Board for this project (IRB number: 20150002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all faculty, students, PWD and non-PWD standardised patients who were involved in the Singapore Institute of Technology Bachelor of Science in Occupational Therapy degree programme. In addition, we would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Associate Professor Tham Kum Ying, Education Director of Tan Tock Seng Hospital Pre-Professional Education Office and senior lecturers Miss Heidi Tan and Mr Lim Hua Beng from the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Funding

Funding was provided from the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE Tertiary Education Research Fund grant: R-MOE-A203-A002).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest concerning any aspect of this research.

References

Kowitlawakul, Y., Chow, Y., Salam, Z., & Ignacio, J. (2015). Exploring the use of standardized patients for simulation-based learning in preparing advanced practice nurses. Nurse Education Today, 35(7), 894-899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.03.004

Lim, S. M., Tan, B. L., Lim, H. B., & Goh, Z. A. G. (2018). Engaging persons with disabilities as community teachers for experiential learning in occupational therapy education. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(1), 36-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1569186118783877

Long-Bellil, L. M., Robey, K. L., Graham, C. L., Minihan, P. M., Smeltzer, S. C., Kahn, P., & Alliance for Disability in Health Care Education. (2011). Teaching medical students about disability: The use of standardized patients. Academic Medicine, 86(9), 1163-1170. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b5dc

Minihan, P. M., Bradshaw, Y. S., Long, L. M., Altman, W., Perduta-Fulginiti, S., Ector, J., … Sneirson, R. (2004). Teaching about disability: Involving patients with disabilities as medical educators. Disability Studies Quarterly, 24(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v24i4.883

Wells, T. P. E., Byron, M. A., McMullen, S. H. P., & Birchall, M. A. (2002). Disability teaching for medical students: Disabled people contribute to curriculum development. Medical Education, 36(8), 788-790. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01264_1.x

*Lim Sok Mui

Singapore Institute of Technology,

SIT@Dover, 10 Dover Drive,

Singapore 138683

Email: may.lim@singaporetech.edu.sg

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 32-40

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/OA2194

Suriyakumar Mahendra Arnold1, Sepali Wickrematilake2, Dinusha Fernando3, Roshan Sampath1, Palitha Karunapema4 & Pasyodun Koralage Buddhika Mahesh5

1Quarantine Unit, Ministry of Health Sri Lanka; 2Regional Director of Health Services Office, Matale, Sri Lanka; 3Regional Director of Health Services Office, Puttalam, Sri Lanka; 4Health Promotion Bureau, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka; 5Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Background: The duties of Public Health Inspectors (PHI) includes those related to food legislation. Effective methods are being explored in providing refresher training for them amidst the constraints of resources.

Objective: To assess the knowledge, attitudes and skills of the PHI on food legislation and to evaluate the effectiveness of a Distance Education (DE) programme in improving these.