Deeper conversations: Palliative care education for pharmacists makes a difference

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 22-31

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/OA2173

Andrea Thompson1, Tanisha Jowsey1, Helen Butler1, Augusta Connor2, Emma Griffiths2, Hadley Brown2 & Marcus Henning1

1University of Auckland, New Zealand; 2Mercy Hospice, Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to identify the impact of a series of palliative care educational packages on pharmacists’ practice for improved service delivery. We asked, what are the educator and learner experiences of a short course comprised of workshops and a series of palliative care learning packages, and how have learners changed their practice as a result of the course?

Method: Semi-structured interviews were conducted and transcribed verbatim. Interpretive thematic analysis was undertaken.

Results: Eight people participated in this study; five pharmacists who had completed learning packages in palliative care and three educators who facilitated teaching sessions for the learning packages. The teaching and assessment approaches were applied and transferable to the clinical setting. The teaching strategies stimulated engagement, enabling participants to share their ideas and personal experiences. Participants’ understanding of palliative care was improved and they developed confidence to engage in deeper conversations with patients and/or their families and carers. Although the completion of assessment for the learning packages enabled credit for continuing professional development, their impact on the long-term practice of pharmacists was not established.

Conclusions: The findings of this study suggest that interactive teaching methods assisted the interviewed pharmacists to further develop their understanding of palliative care, and communication skills for palliative care patients and/or their families/carers. Pharmacists were better equipped and felt more comfortable about having these potentially difficult conversations. We recommend educators to place more emphasis on reflective activities within learning packages to encourage learners to develop more meaning from their experiences.

Keywords: Palliative Care Education, Pharmacist, Hospice, Interactive Learning, Communication, Learning Packages

Practice Highlights

- The course studied informs pharmacists’ practice for improved service delivery.

- The course led to more meaningful palliative care conversations.

- Interactive teaching methods supports learner engagement.

- Educators sharing personal experiences supports learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

There have been recommendations in the literature for over 30 years that pharmacists should receive more education around end-of-life issues and care (Dickinson, 2013). While inadequate training and knowledge in palliative care leads to poor palliative care provision (Furstenberg et al., 1998; Vernon, Brien, & Dooley, & Spruyt, 1999), effective palliative education can positively transform care provision (Institute of Medicine, 2015).

Research shows that effective palliative care education for pharmacists can deepen their understanding of their role in symptom and therapy management and psychosocial care during end-of-life stages, including reducing death anxiety among patients (Atayee, Best, & Daniels, 2008; Dickinson, 2013; Needham, Wong & Campion, 2002). Learning about palliative care encourages collaboration and continuity in service provision, and appropriate, timely and individualised care (Dickinson, 2013). Additionally, with extra training, community pharmacists can become more actively involved in their palliative patients’ care, including providing patient education, prescribing advice to physicians and facilitating continuity between healthcare settings (O’Connor, Pugh, Jiwa, Hughes, & Fisher, 2011). Australian community pharmacists report that completing a flexible online palliative care education programme positively impacts their practice (Hussainy, Marriott, Beattie, Nation, & Dooley, 2010). Hussainy et al. (2010) recommend future educational courses to include face-to-face weekly workshops in order to increase participation. In New Zealand, undergraduate pharmacy students receive palliative care training and upon graduation they manage various palliative care needs. To booster pharmacist palliative care knowledge and communication skills, and in response to the call from Hussainy et al. (2010), in 2016, educators at a metropolitan hospice in New Zealand ran a short course for pharmacists. The authors, including the educator participants in this study, were not involved in the course design. Here we explore participant experiences of the course including application of new knowledge/skills to practice.

The seminal pedagogical approaches of Schön (1983), Kolb (1984) and Knowles (1984) are relevant. Learning occurs when professionals reflect on their tacit knowledge and make sense of their experiences; therefore reflective practice is a central pedagogical approach (Schön, 1983). With this in mind, opportunities for reflective practice ought to be integrated into the design of educational initiatives. Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning model suggests learners have a concrete experience and then reflect on it, enabling them to formulate abstract concepts and generalisations. Learners can then try out their new understanding through the process of active experimentation. The need to be self-directed, the role of the learner’s experiences, motivation, and readiness to learn are examples of assumptions embedded in Knowles’ adult learning theory (Knowles, Holton, & Swanson, 2015).

In this paper, we explore the course in terms of teaching delivery and learning. We undertook a small interpretive thematic study to explore the participants’ experiences of the course. It is important for educators to be involved in researching and reflecting on their own teaching (Henning, Hu, Webster, Brown & Murphy, 2015; Steinert, Cruess, Cruess, & Snell, 2005) and we therefore included the teaching staff as participants alongside learner participants in this study.

A. Research Questions

We asked, what are the educator and learner experiences of a short course comprised of workshops and a series of palliative care learning packages, and how have learners changed their practice as a result of the course?

II. METHODS

A. Participants and Description of Educational Intervention

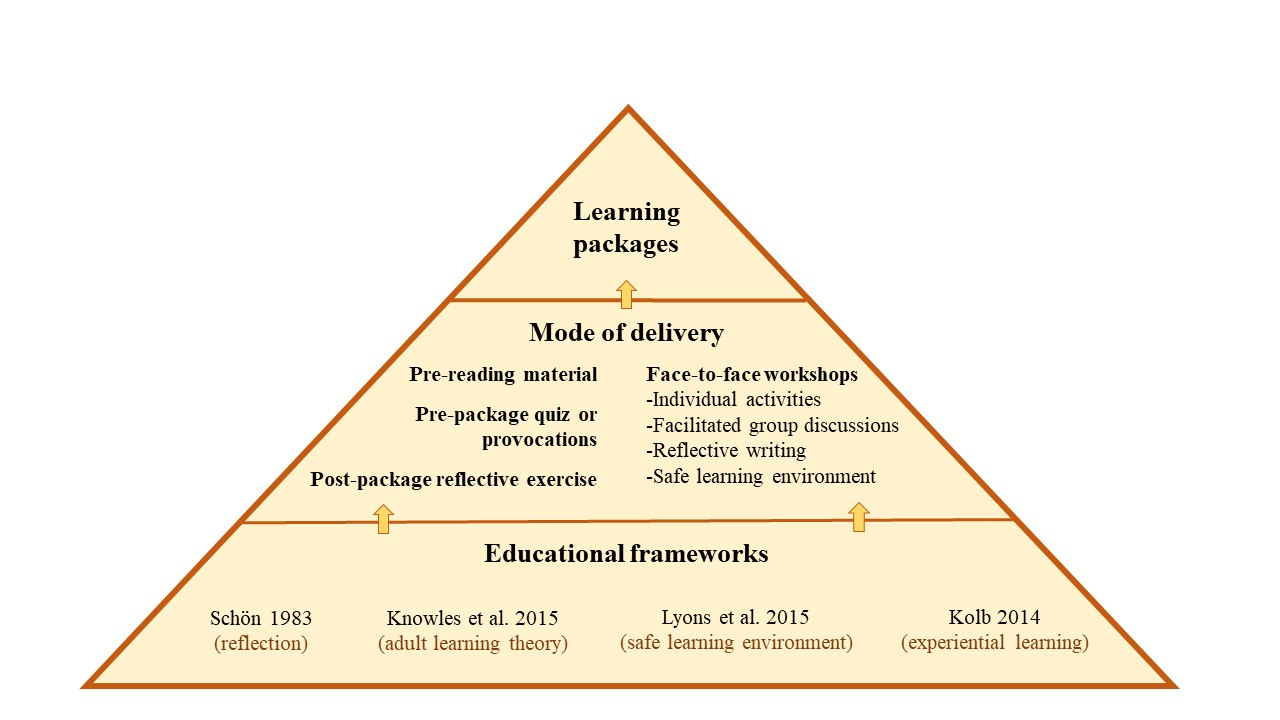

Learner participants were pharmacists who were enrolled in the course. The course learning packages were part of Hospice New Zealand’s Fundamentals of Palliative Care education programme (Appendix A). Figure 1 outlines the mode of delivery and educational frameworks for the learning packages. A two-hour workshop was offered for each learning package and the participants were given access to online resources such as a workbook, pre-reading and reflection activities. Learners were required to complete the pre-reading and reflection activities prior to each workshop. Learners engaged in classroom-based teaching activities, which largely included group discussions. The total number of learning packages that each learner participant completed is shown in Appendix A.

Figure 1. Mode of delivery and educational frameworks

Educator participants were three experienced facilitators (with pharmacy and nursing backgrounds) who were employed by the hospice. Each had an interest in education and had undertaken formal training sessions in palliative care delivery prior to facilitating the course.

B. Data Collection

Course educators and learners were invited via email to partake in a one-off face-to-face or phone interview to discuss their experiences of the course. One member of the research team (author 4) conducted all interviews following a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix B). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were collected between December 2016 and March 2017.

C. Data Analysis

Following Morse and Field (1995) and Saldaña(2016), we used general purpose interpretive thematic analysis. Transcripts were de-identified then uploaded into a qualitative data management system, QSR NVivo 11 software. Three members of the research team (authors 1, 2 and 7) read the transcripts and iteratively created a coding scheme. This involved looking for recurrent words, phrases and concepts within the data, which were termed codes. An initial coding scheme was developed iteratively containing primary codes, subsidiary codes and their definitions. There was a defined protocol for when to code the concepts. Two members of the research team (authors 1 and 2) independently coded each transcript and this coding was then checked by author 7 to ensure consistency and rigour. Two of our authors (3 and 5) were educator participants in this study. They were interviewed by a member of the research team, using the same questions posed to the third educator participant. To minimise bias, these authors were not involved in any aspect of the data analysis.

As the analysis progressed, some of the codes and sub-codes and their definitions were modified to ensure they conveyed the meaning participants had expressed during interviews. Assumptions about the relationships within and between concepts were proposed and explored. The codes were iteratively formed into themes and subthemes (Table 1). These themes were manually cross-checked for consistency. The QSR NVivo 11 software query functions were used to confirm relationships between themes and subthemes. These themes were discussed and refined between the three members of the analysis team.

|

Theme |

Subthemes |

|

A. Application to Practice |

1) Developing an understanding of palliative care 2) Developing empathy, listening and communication skills |

|

B. Learner Engagement |

1) Methods of teaching 2) Engagement – interactive style of teaching works 3) Drawing on personal experience 4) Feeling safe to share and learn |

|

C. Assessment and Evaluation |

1) The role of assessment and evaluation |

Table 1. Themes and subthemes of participant experiences

III. RESULTS

Eight females participated in this study, including five learners (course participants) and three educators. Their reflections on the course that they had attended as either an educator or learner rotated around three core themes: (1) application to practice, (2) learner engagement, and (3) assessment and evaluation (Table 1).

A. Application to Practice

Learner participants reported that the packages had increased their sense of preparedness for having real-life discussions with patients and family members/carers about death and dying/palliative care options, and ethical issues. Learners reported that this sense of preparedness had encouraged them to engage more deeply in conversations concerning palliative care.

1) Developing an understanding of palliative care: Educator and learner participants said the course enhanced their skills and understanding of communication with patients, their families/carers and other health professionals. Learners particularly valued information concerning the following subjects: the impact of a cancer diagnosis on significant others; medication; pharmacology; symptom and pain management; caring for palliative patients; ethical dilemmas; and dementia. A greater understanding of palliative care meant that learners reported they found they were able to make decisions about pharmaceuticals (without needing to check with another health professional), which they saw as likely to save time while maintaining quality of care. Further, learners’ understanding was influenced by the educators’ passion for teaching in the area of palliative care.

You might be thinking why on earth are they using Dexamethasone to increase this patient’s appetite – that doesn’t sound right. I need to ring the doctor. Whereas now they understand this is normal, this is the dose range, so they’re better equipped to supply the medication because they understand why. They’re not having to constantly ring the GP [general practitioner].

(Educator 1)

They [educators] know their topic inside out and they do their best to pass on … every ounce of knowledge that they have, which is great to see in colleagues. I just found it incredibly, inspiring to have that sort of passion for a topic.

(Learner 2)

2) Developing empathy, listening and communication skills: The learning modules enabled learner participants to develop awareness, empathy, and communication skills–particularly listening skills. They gave specific examples of empathic behaviour when dealing with patients and their families, for example, recognising and attempting to understand the multiple losses and life changes one might experience with a cancer diagnosis. Further, the content and delivery of the learning packages gave learners opportunities to be more prepared to engage in difficult conversations around death and dying.

It’s just being able to have more empathy for the people because you appreciate what they’re going through and what’s happening … just being a bit more available I suppose and realise in the end you spend time listening to what they have to say and trying to do the best for them.

(Learner 1)

And I guess when I’m talking to people, [recognising] that they’re going through a lot of losses and because of their cancer for example, they may have lost their job, I mean, if they can’t work anymore, their role in the family, they may have physical changes and loss around that.

(Learner 3)

The importance of ‘giving special time’ for conversation was an additional skill participants learned through completion of the modules. They recognised the importance of moving beyond the patient’s prescription and taking time to listen and engage in conversation with the patients and/or their families/carers.

Well actually at the time we had a customer–a man whose wife was dying of cancer, and I think instead of taking the prescription and things like that, you went out and took a special time and talked to them and spent a bit of time without actually asking too many specific questions.

(Learner 5)

In addition to communicating with patients and their families/carers, learner participants reported that the delivery of the learning modules helped equip and gave learners confidence to communicate more effectively with other health professionals.

“I deal a lot with rest homes and private hospitals so being able to assist the RNs [registered nurses] and to be able to relate to them.”

(Learner 2)

“And so, I sort of feel a lot more comfortable about that and comfortable talking to the doctors, you know, when something’s happening. So, I’ve learnt that.”

(Learner 4)

B. Learner Engagement

1) Methods of teaching: All participants discussed methods of teaching as having direct impact on their learning. Educator participants discussed teaching methods in more depth and greater frequency than pharmacist learner participants. They identified that when interactive strategies were utilised (videos, small group activities, case scenarios, demonstrations, and brainstorms), the learners absorbed/embedded more information and valued the teaching material more than when the information was presented didactically.

If I have to use a PowerPoint [slide presentation] I will learn it so that it’s behind me and I’m speaking to the audience and using eye contact, engaging from them their interest and whether they’re understanding. And I like to encourage questions to be asked as I’m talking because that then helps to add another layer of explanation. I also like case scenarios and preparing a case scenario or an ethical situation for groups to break off and discuss in their small groups and then to feedback so that each group can learn from everybody else.

(Educator 1)

The exception to this pattern was Educator 3’s observation that didactic teaching was an effective teaching strategy to begin the learning session, as it is a teaching format familiar to learners. Once the class was underway a more engaging method was needed.

“[Learners] were quite happy to be led initially, [using] didactic teaching. But I don’t think the sessions would have been as effective if we had continued that route.”

(Educator 3)

The relevance of content was also important to both the educator and learner participants. They valued material that was relevant and applicable to the pharmacists’ ‘specific care populations and practices of care.’

I was satisfied that I was able to provide consultant specialist advice and make it real for the pharmacists…. I put in a number of extra slides that were specific to pharmacists and some of the pharmacology of the drugs etcetera.

(Educator 1)

“It was kind of practical stuff [content] that you could easily translate when dealing with people when they came into the pharmacy.”

(Learner 1)

2) Engagement–Interactive style of teaching works: The teaching methods that learner participants had most to say about were interactive ones. This included facilitated whole-group conversation that was supported by small group activities.

There were a lot of different points of view and a lot of different people who were at different levels of experience in different areas and I think having the whole group there that were all pharmacists was really helpful. We all learned from each other.

(Learner 3)

In contrast, when educators discussed interactive teaching, they talked about it in terms of group dynamics and managing the discussions so that all learners had opportunity to voice their opinions.

There’s nothing worse than having somebody that just has to answer every question, has to share everything because they just need to be heard. So, you have to manage that and … manage the person that just sits there and doesn’t say anything.

(Educator 2)

3) Drawing on personal experience: Three educators and two learners reported that some educators drew on their personal experience–such as from the hospice pharmacist setting–to illustrate the relevance of material. When learners discussed their relevant personal experiences, it was equally valued.

“We all learned from each other.”

(Learner 3)

“We even had one pharmacist kind of stand up and say ‘This happened to me and I want you guys to learn from this’, so there was a lot of them talking about their experiences and sharing stuff.”

(Educator 3)

A learner reflected that the course material had value for her in her personal life.

I’d also gone through it [living and caring for a palliative care patient] with a flatmate early on and I felt that I hadn’t actually coped with it particularly well. So, it [the course] was a little bit for my own good as well.

(Learner 5)

Likewise, an educator made the observation that the course material was applicable to learners in their personal as well as their professional lives.

There was a strong feeling from pharmacists that they were also doing this to learn for their own personal lives because everybody will be touched by palliative care at some point in their lives, whether it be family or friends and it’s helped them to be better equipped with that.

(Educator 1)

The telling of personal experience can be linked with our first theme of Developing empathy, listening and communication skills. It is both telling and listening that comprises effective communication, which is core to pharmacist practices of care.

4) Feeling safe to share and learn: Feeling safe is important to supporting people’s learning. This was explicitly discussed by participants, and implicitly presented in other participants’ accounts.

She [Educator 2] talked to us, she encouraged you to give your opinion or your thoughts as well and you were never made to feel like what you said wasn’t right or was not significant. I thought she was great. It was very much an open forum, so you could relate, add bits in or ask questions and you felt comfortable doing that.

(Learner 4)

Educators were strategic in providing effective learning safe learning environments:

One of the skills of palliative care education is talking about topics that can be really quite difficult for some people if they’ve had a recent loss or they’ve had a situation in their personal life and it’ll trigger, so ground rules are really important to try and keep–to make sure people feel safe. So, you ensure when you start a session that people know that they can share stuff of a personal nature, but that information stays in the room and that it’s not to go outside. And you want people to be respectful.

(Educator 2)

C. Assessment and Evaluation

1) The role of assessment and evaluation: Educator participants highlighted the importance of assessment to enhance learning. Two assessment methods; reflective activities undertaken during the learning packages and quizzes completed at the end of the packages were formatively assessed methods. Educator participants pointed out there is a mechanism for assessment to be recognised by the Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand. In this case, successful completion of assessment therefore becomes a summative assessment.

“[The] Pharmaceutical Society approves questions and if participants gain more than 80% then … the Society awards them learning points that contribute to their compulsory continuing education.”

(Educator 1)

Along with the assessment methods described, the Hospice NZ programme gives learners the opportunity to complete an evaluation which includes questions about learning value for each learning package. The inclusion of assessment and evaluation methods fosters learners to think about how process (teaching delivery) and content have contributed to their learning.

Although educators promoted the merits of assessment comprising part of the learning modules, they acknowledged that assessment gauges learning only in the short term. It is not possible to determine the long-term impact on practice from the assessment and evaluation methods currently utilised. Further, participants identified some confusion around the reflective activities.

“We struggle with assessing their learning long-term – what have they taken away a year later? What are they using in their practice? That’s what we haven’t been able to establish.”

(Educator 1)

“Participants appeared confused about the requirements for the pre and post session reflective activities which they were required to complete in the learning packages.”

(Learner 1)

IV. DISCUSSION

Effective palliative education for pharmacists enables participants to understand their role in end of life care, reduces death anxiety, prepares them to relate to people who are dying and facilitates psychological and emotional competence (Dickinson, 2013). It offers people knowledge and confidence to engage in the types of conversations that enrich peoples’ lives by making them feel heard and cared for. Dau Voire said, “be brave enough to start a conversation that matters” (Bravery Sayings & Bravery Quotes, n.d.). Is it bravery for pharmacists to engage patients in conversations about life and death? It absolutely is because the conversation may necessitate reflecting on your own life, mortality, and wishes.

We have shown that pharmacists valued this palliative care course because it developed key skills–and increased their bravery–to engage in deeper, more meaningful palliative care conversations in their professional and personal lives. We discuss the findings in turn.

A. Learning Engagement

Teaching delivery, which is primarily focused on interactive teaching methods such as small group activities, case scenarios, demonstrations, discussions and brainstorms markedly supported learner engagement. They valued opportunities to learn through discussing learner and educator experiences. These findings are consistent with Knowles’ adult learning theory, which suggests that the learners’ experiences ought to be tapped into (Knowles, et al., 2015). Teachers can help learners by using experiential techniques to acknowledge and utilise learners’ experiences through group discussions, activities to foster reflection, simulation exercises, and problem-solving activities (Knowles et al., 2015; Kolb, 1984; Schön 1983). In our view, one of the strengths of the learning packages is that they align with key educational frameworks (Figure 1).

Learners and educators in this study promoted a safe learning environment to optimise participation and learning (Lyons et al., 2015). This is echoed by existing education literature (Brown, 1988; Douglas, 1976). A safe climate, atmosphere or environment enables participants to feel comfortable about discussing personal experiences, including those which are difficult or challenging.

B. Assessment and Evaluation

When reflection is not encouraged in the clinical setting learning opportunities may be lost (Branch & Paranjape, 2002; Schön, 1983). In this course, learning was promoted through reflection and this was valued by learners, although they reported confusion about requirements for reflection activities. The opportunity for completion of modules to contribute to pharmacists’ continuing professional development (CPD) requirements was a key driver for participants completing the summative assessment. It is unlikely that meeting CPD requirements is the sole requirement for engaging in CPD. Further motivators for CPD may be to enhance professional knowledge and competence (Ryan, 2003).

C. Application to Practice

Several elements of the course were reportedly taken forward by participants to change their practices of care which had the flow-on effect of reducing their need to contact another health professional (for example, the patient’s general practitioner) to assist in decision-making processes. This improved the patient’s continuity of care. The value of palliative education is supported by the evaluation of an online programme in palliative care for pharmacists which demonstrated that the programme positively influenced the knowledge, confidence and practice of community pharmacists (Hussainy et al., 2010).

Delivery of the learning packages enabled pharmacists to develop a greater understanding of the impact of life-limiting illnesses and fostered both their development of empathy and ability to communicate with patients and their families and/or carers. The need for developing communication skills was strongly emphasised in a study which examined the community pharmacist’s role in palliative care (O’Connor et al., 2011). Emotional issues were seen as a major source of stress for general practitioners in an earlier study that identified the importance of the need for training and education to support general practitioners in managing emotional responses for palliative care patients and their families (O’Connor, Fisher, & Guilfoyle, 2006).

D. Limitations

Only females consented to participate in this study. We cannot speak to male pharmacist experiences of the course. The number of course participants was small and we had difficulty recruiting people to our study, partly because the interviews were held several months after the conclusion of the course. Our sample size was therefore small and our findings may not be generalisable. To increase study participation, future research of palliative care pharmacy courses could seek to recruit participants on workshop days or within a week of the course conclusion. Two of the authors on this paper were participants in the study. They were not involved in any aspect of the data analysis but they did contribute to the introduction and discussion sections of this article. The study did not establish the longer-term impact of the educational initiative on pharmacists’ practice. This is an opportunity for future research.

V. CONCLUSION

It is clear that effective palliative care education such as the learning packages discussed here is valued by pharmacists and relevant to their practice. Pharmacists in this study found the learning packages enhanced their understanding of palliative care, sharpened their communication skills and bolstered their confidence to engage in deeper conversations with patients and their families/carers and other health professionals. The interactive teaching methods promoted participant engagement and gave them opportunities to share their ideas and personal experiences and to listen to the experiences of others. Improving communication was a key feature for participants in this study. We therefore recommend that community pharmacists continue to be offered effective palliative care education, and that promotion of communication skills remain central to course method and content. An increased focus on critical reflection activities within such courses needs to be encouraged so that pharmacists can make meaning of their experiences and learning opportunities are not lost.

Notes on Contributors

Andrea Thompson is a Professional Teaching Fellow at the Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland.

Tanisha Jowsey is a medical anthropologist and a Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland.

Helen Butler was formerly employed at a Hospice in New Zealand and is now a Professional Teaching Fellow in the School of Nursing at the University of Auckland.

Augusta Connor, was formerly a research assistant at a Hospice in New Zealand and now works in health economics in the United Kingdom.

Emma Griffiths works at a Hospice in New Zealand as a specialist palliative care pharmacist.

Hadley Brown was formerly employed at a Hospice in New Zealand and is now self-employed. He has been involved in management within in the New Zealand hospice sector.

Marcus Henning is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, University of Auckland.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Reference Number: 016800).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participants who shared their experiences of teaching and learning.

Funding

A research assistant who conducted and transcribed the interviews was funded by Mercy Hospice, Auckland, New Zealand.

Declaration of Interest

Two authors were participants in the study. Although they were involved in the design of the study and contributed to writing the paper they were not involved in analysis of the data.

References

Atayee, R., Best, B., & Daniels, C. (2008). Development of an ambulatory palliative care pharmacist practice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(8), 1077-1082. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2008.0023

Branch, T., & Paranjape, T. (2002). Feedback and reflection: Teaching methods for clinical settings. Academic Medicine, 77(12), 1185-1188. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200212000-00005

Bravery Sayings & Bravery Quotes (n.d.). Bravery sayings and quotes. Retrieved from http://www.wiseoldsayings.com/bravery-quotes/

Brown, G. (1988). Effective teaching in higher education. London: Methuen.

Dickinson, G. (2013). End-of-life and palliative care education in US pharmacy schools. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 30(6), 532-535. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909112457011

Douglas, T. (1976). Groupwork practice. London: Tavistock Publications.

Furstenberg, C., Ahles, T., Whedon, M., Pierce, K., Dolan, M., Roberts, L., & Silberfarb, P. (1998). Knowledge and attitudes of health-care providers toward cancer pain management: A comparison of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in the state of New Hampshire. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 15(6), 335-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00023-2

Henning, M., Hu, J., Webster, C., Brown, H., & Murphy, J. (2015). An evaluation of Hospice New Zealand’s interprofessional fundamentals of palliative care program at a single site. Palliative & Supportive Care, 13(3), 725-732.

Hussainy, S., Marriott, J., Beattie, J., Nation, R., & Dooley, M. (2010). A palliative cancer care flexible education program for Australian community pharmacists. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 74(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj740224

Institute of Medicine (2015). Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing, Key End-of-Life Issues. Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Knowles, M. (1984). The adult learner: A neglected species (3rd Ed.). Houston: Gulf Pub. Co.

Knowles, M., Holton, E., & Swanson, R. (2015). The adult learner. (8th Ed.). New York: Routledge.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall c1984.

Lyons, R., Lazzara, E. H., Benishek, L. E., Zajac, S., Gregory, M., Sonesh, S. C., & Salas, E. (2015). Enhancing the effectiveness of team debriefings in medical simulation: More best practices. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 41(3), 115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(15)41016-5

Morse, J. & Field, J. (1995). Qualitative research methods for health professionals (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Needham, D. S., Wong, I. C. K., & Campion, P. D. (2002). Evaluation of the effectiveness of UK community pharmacists’ interventions in community palliative care. Palliative Medicine, 16(3), 219-225. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216302pm533oa

O’Connor, M., Fisher, C., & Guilfoyle, A. (2006). Interdisciplinary teams in palliative care: A critical reflection. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 12(3), 132-137. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.3.20698

O’Connor, M., Pugh, J., Jiwa, M., Hughes, J., & Fisher, C. (2011). The palliative care interdisciplinary team: Where is the community pharmacist? Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14(1), 7-11. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0369

Ryan, J. (2003). Continuous professional development along the continuum of lifelong learning. Nurse Education Today, 23(7), 498-508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0260-6917(03)00074-1

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd Ed.). London: Sage.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Steinert, Y., Cruess, S., Cruess, R., & Snell, L. (2005). Faculty development for teaching and evaluating professionalism: From programme design to curriculum change. Medical Education, 39(2), 127-136.

Vernon, J., Brien, J., Dooley, M., & Spruyt, O. (1999). Multidisciplinary treatment paths and medication management of palliative care patients. Proceedings of the Australian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists and Toxicologists, 7, 74.

*Andrea Thompson

University of Auckland,

Building 599, Level 12,

Auckland City Hospital

Private Bag 92019,

Auckland 1142

Tel: +6499231906

Email: andrea.thompson@auckland.ac.nz

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.