“Modified World Café” workshop for a curriculum reform process

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2019, 4(1), 55-58

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-1/SC2000

Ikuo Shimizu, Junichiro Mori & Tsuyoshi Tada

Centre for Medical Education and Clinical Training, Shinshu University, Japan

Abstract

Consensus formation among faculties is essential to curriculum reform, especially for the clinical curriculum. However, there is limited evidence on the model of workshop that is necessary for curriculum reform. In the current project, we aimed at developing a beneficial workshop method for building consensus and reaching educational goals in curriculum reform. We compared the two types of workshop models. First, we conducted workshops using standard group work model with fixed group members. Then we used a revised workshop model. In the revised model, all but one group member moved their seats after the first round of discussion. In addition, we reserved time for plenary presentations and discussions after each round. We called the model “Modified World Café” workshop named after World Café, a collaborative dialogue method. With this design, not only we were able to achieve significant improvement of appropriate products and better consensus, but also attained several educative goals. Since the model combines characteristics of the standard group work and World Café concept, it might be useful in facilitating the sharing of new knowledge and creating consensus.

Keywords: Curriculum Reform, Workshop, Consensus Building, World Café

I. INTRODUCTION

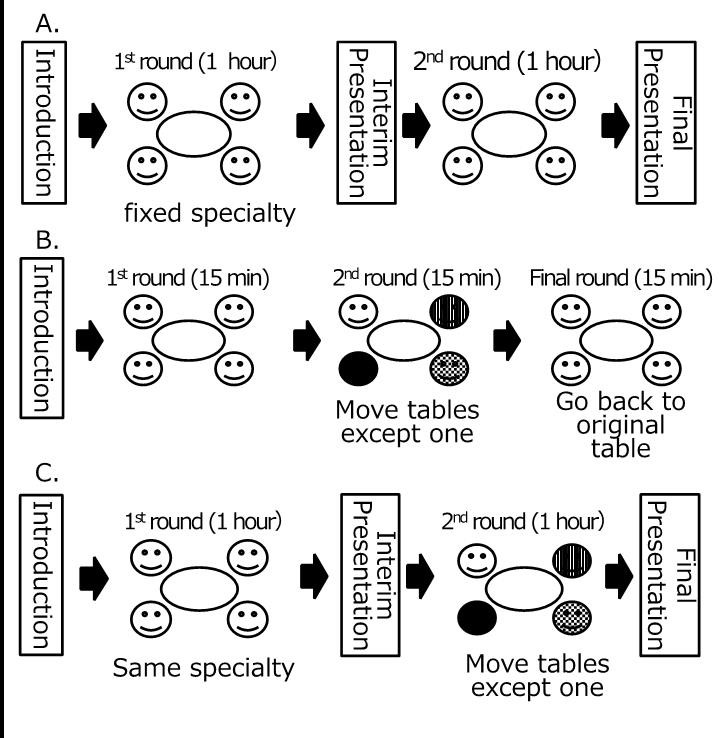

When medical education managers conduct the curriculum reform in medical schools, they must plan for an effective implementation of the new outcomes of the curriculum, especially in the curriculum reform of clinical years when more diverse community clinician-educators at various educational environments are involved (Takamura, Misaki, & Takemura, 2017). Therefore, it is desirable that the curriculum is reformed by taking into accounts of the opinions from stakeholders at multiple specialties and reaching a consensus among them. In medical education, workshops have been performed for such a reform (Steinert, 2014). The standard workshop consists of small group discussions with fixed members throughout the schedule (Figure 1A), however, the effectiveness of this workshop design has not been well explored.

The World Café (Brown & Isaacs, 2005), a series of short group dialogues with table rotations (Figure 1B), is useful for building consensus since it relies on a participatory and collaborative network of conversations (Health Profession Opportunity Grants, 2015). However, one concern to apply World Café for establishing outcomes is that it may not be suitable to establish a new curriculum since it is just a dialogue process rather than a workshop to construct valid products and short discussion time may make discussions superficial and unfruitful.

Therefore, we designed a hybrid program of the standard workshop described above and World Café: the “Modified World Café” (Figure 1C). In this design, participants started the first round by providing a goal within a group to work on. After the first round, they share the discussion in the interim plenary presentation, then all members except one in each group (a “host”) move to a new table and start a new round of discussion. Finally, they return to their original table to summarise their discussions and finalise the product with a final presentation. While “Modified World Café” is similar to World Café in terms of process whereby all members except for one in each group move seats, there are two major differences: (1) each round is longer to discuss more deeply, and (2) participants have to collect opinions twice for interim and final presentations. These revisions are intended to finalise the products. We aimed at (1) evaluating the effectiveness of the “Modified World Café” to mix the various opinions and reach better consensus on the expected outcomes among participants, and (2) exploring the participants’ perceptions.

Note: 1A. The standard workshop (i.e., the model without moving tables),

1B. World Café dialogues (Brown, 2005), and

1C. “Modified World Café” workshop.

Figure 1. Three types of workshop models discussed in this article

II. METHODS

A. Setting

Shinshu University School of Medicine in Japan extended its clinical clerkship program from 15 to 21 months in 2015, by adding a 6-month elective clerkship program. In the new program, students are expected to rotate among the community teaching hospitals to acquire clinical competencies. Because of this reform, we conducted workshops to establish the learning outcomes of the new clinical clerkship program and share the outcomes from the 2014 to 2015 academic year. The workshop participants are clinician-educators of community teaching hospitals who teach medical students in the clinical clerkship program. Every teaching hospital was asked that at least one clinician-educator per hospital participated in one of the series of workshops.

B. Design of workshop

In the workshops, we used the following two workshop models for comparison. Firstly, we conducted two workshops with the standard group work model (Figure 1A), in which the participants engaged in two rounds of small group discussions. The groups consisted of five to seven participants each and were formed according to their clinical specialty, and members were fixed. Each group was asked to establish outcomes of its specialty for the reformed curriculum during the couple of rounds. Faculties of Shinshu University Hospital participated and facilitated the discussions. There were two presentation opportunities: interim and final sharing on what they have discussed.

We, then, conducted three workshops using the “Modified World Café”. The expected product, number of participants, the number and length of rounds, and the presence of facilitators were the same as the standard group work model. As described in the Introduction part (Figure 1C), all members except one in each group (a “host”) move to a new table in the second round. Two presentations (interim and final) were performed. The participants were briefed on process at the beginning of each workshop.

C. Evaluation

To evaluate these workshop models, the participants were asked to complete two anonymous questionnaires. The first one was an open-response evaluation sheet designed for participants to write their own perceptions (e.g. benefits, demerits, suggestions) on the group work in the workshop. The comments were analysed using thematic analysis, which involved iteratively exploring the data and comparing and refining the identified categories. Two team members read the data iteratively and analysed them thematically using the affinity diagram method (KJ method) (Scupin, 1997), identifying, analysing, and reporting themes within the data and developing an interpretive synthesis of the topic.

The second survey used a questionnaire comprising the following items: (1) the degree of perceived usefulness of the products, and (2) the degree of perceived consent of the products, and (3) the degree of active participation in the workshop. The responses were collected with a 5-point Likert scale ranged from 1 for “strongly disagree” to 5 for “strongly agree,” which we analysed statistically with the t-test.

III. RESULTS

A total of 120 educators from 37 hospitals participated in the five workshops (71 at the initial model and 49 at the revised model). Among them, 77.5% had been involved in postgraduate (residency) clinical teaching. The response rate of the questionnaire was 89.4%.

Analysing the open-response sheet in the initial model enabled the identification of four themes: preference for outcomes, usefulness of collaboration, attitude for participation, and need of inter-specialty discussions. From the comments after the Modified World Café, two more themes were emerged in addition to the four themes in the initial model: (1) suggestive opinions about educational views (“How should we address the diverse characteristics of students?” “Near-peer learning with residents can be useful”) and (2) an educational impact (“teaching strategies at the workplace,” “the importance of outcome-based education,” “an overview of legitimate peripheral participation”), all of which are theoretical bases of clinical clerkships.

The rating of the items in the questionnaire on the 5-point scale revealed that the mean degree of the usefulness of the products significantly improved from 3.77 to 4.00 (p = 0.017). The mean degree of perceived consent of the products also significantly improved from 3.61 to 4.05 (p = 0.001). The degree of active participation in the workshop did not change (4.05 and 3.95; p = 0.256).

IV. CONCLUSION

Our “Modified World Café” workshop shows not only improved the perceived usefulness and built better consensus but also yielded educational achievement from the analysis of open-response sheet. It is probably because of a benefit of World Café, which can visualize and share collective intelligence (Brown & Isaacs, 2005). By hybridizing the characteristics of the standard group work and World Café, our “Modified World Café” workshop can be a more suitable design. The degree of active participation did not change probably because the participants did not join in the workshop voluntarily. Better achievements with the same degree of active participation will still indicate a merit of “Modified World Café”.

On the other hand, there are some limitations. Firstly, since the participants attended only one workshop, our results might not be from any experimental design. Also, only three items were used in the questionnaire, although we observed significant improvement in some perceptions.

Since workshop tends to be dependent on its context (Steinert, 2014), the educational innovation in its design has been hindered. With this regard, our “Modified World Café” workshop may be applicable in other contexts which require highly collective processes for consensus creation, such as patient safety and interprofessional management.

Notes on Contributors

Ikuo Shimizu MD, MHPE, is an assistant professor at the Centre for Medical Education and Clinical Training in Shinshu University. He is also involved in the safety management office at Shinshu University Hospital.

Junichiro Mori, MD, PhD, is a lecturer at the Centre for Medical Education and Clinical Training in Shinshu University.

Tsuyoshi Tada, MD, PhD, is a professor at the Centre for Medical Education and Clinical Training in Shinshu University.

Ethical Approval

This work was approved by the Institutional Research Board at Shinshu University and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki; in particular, anonymity was guaranteed and consented for analysis was obtained.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the other faculty members at the Centre for Medical Education and Clinical Training and the Shinshu University Hospital who contributed to the series of this workshop.

Funding

No funding is involved for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

Brown, J., & Isaacs, D. (2005). The World Café: Shaping our futures through conversations that matter. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Health Profession Opportunity Grants (2015). Using the World Café to Improve Instructor Engagement: A Guide for Health Profession Opportunity Grants Programs. Retrieved 1 March 2018, from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/using-the-world-cafe-to-improve-instructor-engagement-a-guide-for-health-profession-opportunity-grants-programs.

Scupin, R. (1997). The KJ method: A technique for analysing data derived from Japanese ethnology. Human organisation, 56(2), 233-237.

Steinert, Y. (2014). Faculty development: Future directions. In Faculty Development in the Health Professions. Springer Netherlands.

Takamura, A., Misaki, H., & Takemura, Y. (2017). Community and interns’ perspectives on community – Participatory medical education: From passive to active participation. Family Medicine, 49(7), 507–513.

*Ikuo Shimizu, MD, MHPE

Safety Management Office

Shinshu University Hospital

3-1-1 Asahi, Matsumoto 3908621, Japan

Tel: +81 263 37 3359

Email: ishimizu@shinshu-u.ac.jp

Announcements

- Best Reviewer Awards 2025

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2025.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2025

The Most Accessed Article of 2025 goes to Analyses of self-care agency and mindset: A pilot study on Malaysian undergraduate medical students.

Congratulations, Dr Reshma Mohamed Ansari and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2025

The Best Article Award of 2025 goes to From disparity to inclusivity: Narrative review of strategies in medical education to bridge gender inequality.

Congratulations, Dr Han Ting Jillian Yeo and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2024

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2024.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2024

The Most Accessed Article of 2024 goes to Persons with Disabilities (PWD) as patient educators: Effects on medical student attitudes.

Congratulations, Dr Vivien Lee and co-authors! - Best Article Award 2024

The Best Article Award of 2024 goes to Achieving Competency for Year 1 Doctors in Singapore: Comparing Night Float or Traditional Call.

Congratulations, Dr Tan Mae Yue and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors.