Assessment of medical professionalism using the Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX): A survey of faculty perception of relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness

Submitted: 17 April 2020

Accepted: 05 August 2020

Published online: 5 January, TAPS 2021, 6(1), 114-118

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/SC2358

Warren Fong1,3,4, Yu Heng Kwan2, Sungwon Yoon2, Jie Kie Phang1, Julian Thumboo1,2,4 & Swee Cheng Ng1

1Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 2Programme in Health Services and Systems Research, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 3Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 4Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to examine the perception of faculty on the relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the Professionalism Mini Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX) in the assessment of medical professionalism in residency programmes in an Asian postgraduate training centre.

Methods: Cross-sectional survey data was collected from faculty in 33 residency programmes. Items were deemed to be relevant to assessment of medical professionalism when at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8 on a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant). Feedback regarding the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX assessment was also collected from the faculty through open-ended questions.

Results: In total, 555 faculty from 33 residency programmes participated in the survey. Of the 21 items in the P-MEX, 17 items were deemed to be relevant. For the remaining four items ‘maintained appropriate appearance’, ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’, ‘solicited feedback’, and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’, the percentage of faculty who gave a rating of ≥8 was 78%, 75%, 74%, and 69% respectively. Of the 333 respondents to the open-ended question on feasibility, 34% (n=113) felt that there were too many questions in the P-MEX. Faculty also reported that assessments about ‘collegiality’ and ‘communication with empathy’ were missing in the current P-MEX.

Conclusion: The P-MEX is relevant and feasible for assessment of medical professionalism. There may be a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality and empathetic communication in the P-MEX.

Keywords: Professionalism, Singapore, Survey, Assessment

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical professionalism is one of the core Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies and forms the basis of medicine’s contract with society. Unprofessional behaviour during training of junior doctors has been shown to result in future unprofessional behaviour. Assessment of professionalism not only allows for timely feedback to residents to help them improve, but also allows for development of better curriculum to prevent lapses in medical professionalism. The Professionalism Mini-Evaluation Exercise (P-MEX) had previously been identified as a potential observer-based assessment tool (Kwan et al., 2018), but it has not been validated in a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural Asian context such as Singapore. According to International Ottawa Conference Working Group on the Assessment of Professionalism, professionalism varies across cultural contexts, and therefore cross-cultural validation of the assessment tool for medical professionalism is imperative (Hodges et al., 2011). The current assessment tools adopted in local institutions may not cover the entire continuum of medical professionalism. For example, in the Ministry of Health Holdings (MOHH) C1 form which is currently being used for the assessment of residents on a 6-monthly basis, the assessment of professionalism is summative and consists of only three items (1) Accepts responsibility and follows through on tasks, (2) Responds to patient’s unique characteristics and needs equitably, (3) Demonstrates integrity and ethical behaviour.

We aimed to (1) examine faculty perception of the relevance of the P-MEX for assessment of medical professionalism in the local context, and (2) determine the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX as an assessment tool for medical professionalism in Singapore.

II. METHODS

A. Design and Participants

We invited faculty in the SingHealth residency programmes to participate in the study by completing an online anonymous questionnaire in July 2018 to August 2018. Participants were given one week to complete the survey, with three reminder emails sent at one-week, two-weeks and one-month after the deadline for submission. SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study (Reference Number: 2016/3009). Implied informed consent was provided by participants before completing the online anonymous questionnaire.

B. Survey Questionnaire

The P-MEX consists of four domains (Doctor-patient relationship skills, Reflective skills, Time management and Inter-professional relationship skills) and 21 sub-domains. Faculty were asked to rate the relevance of each item in P-MEX using a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant). The faculty were also asked the following open-ended questions to determine the feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX- (1) “In your opinion, is a P-MEX form with 21 items too long, making it not feasible for routine use? If so, which items should be removed?” and (2) “In your opinion, are there any missing items (observable actions of a medical professional) that should be included in this form? If so, what new items should be added?” The questionnaire also included additional questions related to demographic characteristics (age, gender, specialty and number of years since becoming a specialist).

C. Analysis

Items were deemed to be relevant to the assessment of medical professionalism when at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8. This was determined by expert judgement and prior literature (Avouac et al., 2011). For the open-ended questions on feasibility and comprehensiveness, responses were categorised and the number of the respondents who deemed the 21-item P-MEX to be not feasible (too long) or not comprehensive (there were missing items that should be included) are presented.

III. RESULTS

In total, 555 faculty from 33 residency programmes participated in the survey (response rate 44%). The respondents were 59% male, median age 43 years old, age ranged from 30 to 78 years old. Specialists from medical and surgical disciplines made up 39% and 27% of the respondents respectively, with the remaining respondents coming from diagnostic radiology/nuclear medicine, anaesthesiology, paediatrics and emergency medicine (12%, 11%, 6% and 5% of the respondents respectively).

A. Relevance

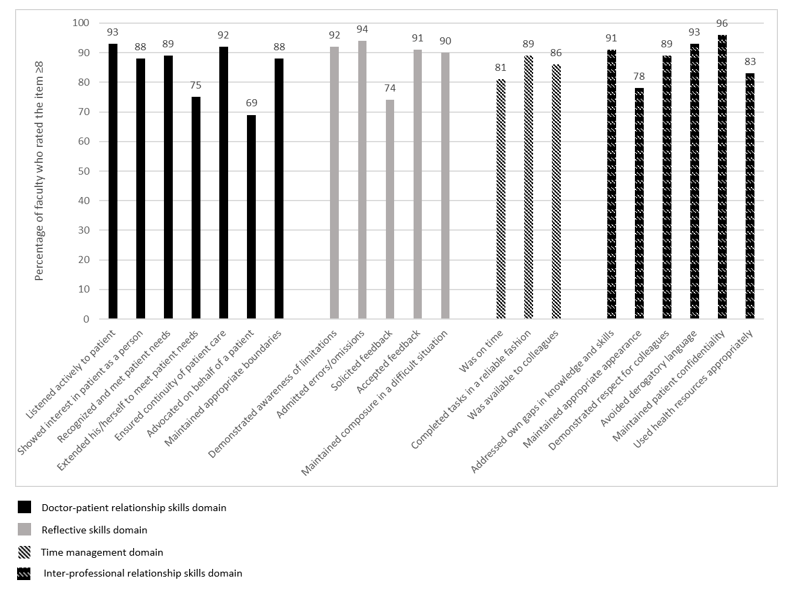

Of the 21 items in P-MEX, 17 items were deemed to be relevant (at least 80% of the faculty gave a rating of ≥8). For the remaining four items ‘maintained appropriate appearance’, ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’, ‘solicited feedback’, and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’, the percentage of faculty who gave a rating of ≥8 was 78%, 75%, 74%, and 69% respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of faculty (n=555) who rated the item ≥8 on the relevance of the item in assessment of medical professionalism using a 0-10 numerical rating scale (0 representing not relevant, 10 representing very relevant).

B. Feasibility

There were 333 respondents for the question “In your opinion, is a P-MEX form with 21 items too long, making it not feasible for routine use? If so, which items should be removed?”, of which 34% (n=113) felt that there were too many questions in the P-MEX assessment form. The top four items chosen to be removed were “solicited feedback” (n=36), “extended his/herself to meet patient needs” (n=27), “advocated on behalf of a patient” (n=25), and “maintained appropriate appearance” (n=23). 208 (62%) respondents felt that the number of questions in the P-MEX assessment form was appropriate.

C. Comprehensiveness

There were 307 respondents to the question “In your opinion, are there any missing items (observable actions of a medical professional) that should be included in this form? If so, what new items should be added?”, of which 28% (n=85) faculty felt that there were missing items. The most frequently mentioned missing items were regarding assessment of ‘collegiality’ (n=54) and assessment of ‘communication with empathy’ (n=12).

Examples of ‘collegiality’ provided by faculty— “Collaboration with other healthcare professionals in the patients’ best interest”, “Demonstration of collaborative behaviour”

Examples of ‘communication with empathy ‘provided by faculty— “Communicate with empathy and effectively to patient and family, taking into account their level of understanding, education and socioeconomic background”, “Communication skills…should embrace empathy, listening skills, discretion, sensitivity and intelligence… sufficient information, counselling, planning and advice regarding medical condition and options.”

207 respondents (67%) felt that the P-MEX was comprehensive for the assessment of medical professionalism.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study provides preliminary evidence on the relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX in the assessment of medical professionalism in an Asian city state. The current study is part of a larger project to culturally adapt and validate the P-MEX. Based on our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the faculty perception on relevance, feasibility and comprehensiveness of the P-MEX in the assessment of medical professionalism in a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic context.

There were four items that were deemed to be less relevant (extended his/herself to meet patient needs, advocated on behalf of a patient, solicited feedback, maintained appropriate appearance). These findings were also similar in a validation study performed in Canada, where the items ‘extended his/herself to meet patient needs’ and ‘advocated on behalf of a patient’ were also frequently marked as ‘not applicable’, suggesting that the two items may be less relevant (Cruess, McIlroy, Cruess, Ginsburg, & Steinert, 2006). Qualitative methods can be used to explore the reasons why these items were deemed to be less relevant. About one-third of faculty felt that P-MEX was too long. Further study is warranted to evaluate the possibilities for shortening the P-MEX to reduce response burden and enhance routine use of the P-MEX.

In addition, our study revealed a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality. Some faculty felt that ‘collegiality’ was missing in the P-MEX despite the presence of items such as ‘demonstrated respect for colleagues’ and ‘avoided derogatory language’. This suggests that collegiality may encompass actions other than demonstrating respect and avoiding derogatory language in the local context, and further reinforces the emphasis of interprofessional collaborative practice.

Faculty also felt that there was also a lack of assessment of ‘communication with empathy’ in the P-MEX. The importance of empathetic communication is also supported by a study in Indonesia, a country in the same region, which found that patients considered communication as the most important attribute of medical professionalism (Sari, Prabandari, & Claramita, 2016).

This study has some limitations. The non-response rate raises concern about possible selection bias. Non-responders may have been less enthusiastic about the assessment of medical professionalism. Medical professionalism is affected by socio-cultural factors, therefore the findings from this study may not be entirely generalizable to another socio-cultural context. In addition, we were unable to elucidate the reasons for disagreement with the relevance of some of the items in the P-MEX as many faculty did not provide feedback and comments. Nevertheless, the findings of this study can serve as basis for future research, especially in countries with similar multicultural backgrounds.

V. CONCLUSION

Faculty agreed that most of the items in the P-MEX were relevant in the assessment of medical professionalism. Majority of the faculty also felt that the P-MEX was feasible to be used routinely in the assessment in medical professionalism. There may be a need for greater emphasis on the assessment of collegiality and communication with empathy in the modified P-MEX.

Notes on Contributors

Warren Fong reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Yu Heng Kwan reviewed the literature, designed the study, collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Sungwon Yoon advised the design of study, analysed data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. Jie Kie Phang collected data, analysed data, and wrote manuscript. Julian Thumboo advised the design of study, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. Swee Cheng Ng advised the design of study, collected data, analysed data, and gave critical feedback to the writing of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this was granted by the SingHealth Institutional Review Board (Reference Number: 2016/3009).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank all the study participants for contributing to this work.

Funding

This research was supported by SingHealth Duke-NUS Medicine Academic Clinical Programme Education Support Programme Grant (Reference Number: 03/FY2017/P2/03-A47). Funder was not involved in the design, delivery or submission of the research.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Avouac, J., Fransen, J., Walker, U., Riccieri, V., Smith, V., Muller, C., … Matucci-Cerinic, M. (2011). Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: Results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 70(3), 476-481. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.136929

Cruess, R., McIlroy, J. H., Cruess, S., Ginsburg, S., & Steinert, Y. (2006). The professionalism mini-evaluation exercise: A preliminary investigation. Academic Medicine, 81(10), S74-S78.

Hodges, B. D., Ginsburg, S., Cruess, R., Cruess, S., Delport, R., Hafferty, F., . . . Ohbu, S. (2011). Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Medical Teacher, 33(5), 354-363.

Kwan, Y. H., Png, K., Phang, J. K., Leung, Y. Y., Goh, H., Seah, Y., . . . Lie, D. (2018). A systematic review of the quality and utility of observer-based instruments for assessing medical professionalism. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10(6), 629-638.

Sari, M. I., Prabandari, Y. S., & Claramita, M. (2016). Physicians’ professionalism at primary care facilities from patients’ perspective: The importance of doctors’ communication skills. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 5(1), 56-60. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.184624

*Warren Fong

SingHealth Rheumatology,

Senior Residency Programme,

20 College Road,

Singapore 169856

Tel: +6563214028

Email: warren.fong.w.s@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 17 March 2020

Accepted: 3 April 2020

Published online: 1 September, TAPS 2020, 5(3), 83-87

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-3/SC2238

Cristelle Chow1, Cynthia Lim2 & Koh Cheng Thoon3

1General Paediatrics Service, Department of Paediatrics, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 2Nursing Clinical Services, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore; 3Infectious Disease Service, Department of Paediatrics, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Background: Effective communication between doctors and patients leads to better compliance, health outcomes and higher doctor and patient satisfaction. Although in-person communication skills training programs are effective, they require high resource utilisation and may provide variable learner experiences due to challenges in standardisation.

Objective: This study aimed to develop and implement an evidence-based, self-directed and interactive online communication skills training course to determine if the course would improve learner application of communication skills in real clinical encounters.

Methods: The course design utilised the Kalamazoo Consensus framework and included videos based on common paediatric clinical scenarios. Final year medical students in academic year 2017/2018 undergoing a two-week paediatric clerkship were divided into two groups. Both groups received standard clerkship educational experiences, but only the intervention group (88 out of 146 total students) was enrolled into the course. Caregiver/patient feedback based on students’ clinical communication was obtained, together with pre- and post-video scenario self-reported confidence levels and course feedback.

Results: There were minimal differences in patient feedback between intervention and control groups, but the control group was more likely to confirm caregivers’/patients’ agreement with management plans and provide a summary. However, caregivers/patients tended to feel more comfortable with the intervention compared to the control group. Median confidence levels increased post-video scenarios and learners reported gains in knowledge, attitudes and skills in paediatric-specific communication.

Conclusion: Although online video-based communication courses are useful standardisation teaching tools, complementation with on-the-job training is essential for learners to demonstrate effective communication.

Keywords: Online Learning, Undergraduate Medicine, Professionalism, Communication Skills, Patient Feedback

I. INTRODUCTION

Effective doctor-patient communication leads to better compliance, health outcomes and higher doctor and patient satisfaction. Online video-based communication skills courses can be feasible, with learners reporting increased confidence in key communication skills (Kemper, Foy, Wissow, & Shore, 2008). However, these evaluation methods have been limited to the Kirkpatrick levels of “reaction” and “learning”, instead of “behaviour” and “results”, which are more reflective of applied learning.

While in-person communication skills training programs simulate clinical environments, they can have inconsistent delivery because facilitators and standardised patients provide variable training experiences. In order to replace traditional role-play sessions, this study aimed to develop and implement a pilot online communication skills course to provide standardised, video-based scenarios in a self-directed interactive learning format using an evidence-based framework.

Our research questions are as follows:

- Would an online communication course improve the application of communication skills in real clinical encounters?

- What is the impact of an online communication course on learner-rated confidence levels in paediatric-specific clinical communication encounters?

- What are the self-reported aspects of learning that participants of an online communication course experience?

II. METHODS

This course design utilised the Kalamazoo Consensus framework (Makoul, 2001) which included the essential elements of clinical communication: Open the discussion, gather information, understand patient’s perspective, share information, reach agreement and provide closure.

Through Bandura’s social learning theory, people learn through observing others’ behaviour. The attitudes and outcomes of those behaviours then guide subsequent actions. This course therefore utilised videos featuring positive doctor-caregiver interactions, to encourage modelling through observation. The 3-5-minute video scenarios acted by practicing healthcare professionals were based on commonly encountered general paediatric clinical situations.

The course was designed using Articulate© software. “Pop-up” prompts highlighting important clinical or communication points, a pre- and post-test and in-video multiple-choice questions were included to increase learner engagement. To evaluate the impact of the course on learner-rated confidence levels, students were shown a clinical vignette, and asked to rate their self-confidence on a 4-point Likert scale before and after each video. Each video concluded with a summary, emphasising the utilisation of the Kalamazoo Consensus Framework.

|

Q1: Did the student introduce his/ her name? |

Q2: Did the student allow you to express your concerns? |

|

⃝ Yes ⃝ No ⃝ Not sure |

⃝ Yes, ALL my concerns ⃝ Not really, only SOME of my concerns ⃝ No, NONE of my concerns |

|

Q3: How much was the student interested in your point of view (e.g. expectations, ideas, beliefs, values) when he/she was asking you questions? |

Q4: How much was the student interested in your point of view (e.g. expectations, ideas, beliefs, values) when he/she was planning and explaining things? |

|

⃝ Very interested ⃝ Somewhat interested ⃝ Somewhat uninterested ⃝ Not interested at all |

⃝ Very interested ⃝ Somewhat interested ⃝ Somewhat uninterested ⃝ Not interested at all |

Q5: Did you feel that the student listened to you? |

Q6: How well do you feel the student explained things to you? |

|

⃝ Listened all the time ⃝ Listened sometimes ⃝ Did not listen at all |

⃝ Very well – I understood all the explanation ⃝ Fairly well – I understood some of the explanation ⃝ Not well at all – I did not understand all of the explanation |

|

Q7: Did the student check if you were agreeable with the management plan? |

Q8: Did the student provide a summary of the problem/ plans at the end of the conversation? |

|

⃝ Yes ⃝ No ⃝ Not sure |

⃝ Yes ⃝ No ⃝ Not sure

|

|

Q9: Overall, how comfortable were you interacting with the student? |

Q10: What do you think this student could improve in? E.g. Be more courteous/ respectful, speak or explain more clearly, listen more, check my understanding, answer my queries etc. |

|

⃝ Very comfortable – I would like to have him/ her be my/ my child’s doctor ⃝ Somewhat comfortable ⃝ Somewhat uncomfortable ⃝ Not comfortable at all – I do not want him/ her to be my/ my child’s doctor |

|

Table 1. Caregiver/Patient Feedback Form

To evaluate the self-reported learning points from the course, students were asked upon course completion to provide course feedback, including free-text completion of the phrase: “Things I have learnt include…” To evaluate whether the course improved the application of communication skills in real clinical encounters, caregiver/patient feedback was obtained towards the end of the paediatric clerkship for all students, regardless of course participation (Table 1). This form was modified based on course content from a family feedback instrument utilised in a paediatric setting (Zimmer, Solomon, Siberry, & Serwint, 2008). Implied informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Final year medical students from a five-year Singapore undergraduate medical program were enrolled over one academic year (2017/2018). Alternate batches (2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th) were enrolled into the course. Each student was provided a unique username and password for course access on any internet-enabled device throughout his/her 2-week paediatric clerkship and course participation was strongly recommended. Students from other batches (1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th) were analysed as controls. All students integrated into paediatric clinical teams, participated in ward rounds and communicated plans to patients/caregivers.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS© Statistics version 25.0 and chi-square analysis was used for patient feedback analysis.

This study was exempted from formal Centralized Institutional Review Board review and implied informed consent was granted by the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board.

III. RESULTS

A total of 146 students were posted to the study institution in academic year 2017/2018 and 88 students were enrolled into the course. There were 80 (90.9%) attempts at the course, of which 76 (95%) students provided course feedback. The median time needed for course completion was 59 minutes. Patient feedback was successfully collected for 94 students, of which 44 (46.8%) attempted the course. Main reasons for unsuccessful collection were fast patient turnovers and patients/caregivers rejecting the request to provide feedback, usually due to perceived insufficient student contact time.

A. Application of Communication Skills – Evaluated via Patient Feedback

Although there were generally no differences in patient feedback between intervention and control groups, the control group was more likely to check with caregivers/patients whether they were agreeable with the management plan (76.0% vs. 56.8%, p<0.05) and provided a summary to the caregiver/patient (74.0% vs. 47.7%, p<0.05). Approaching statistical significance was the finding that caregivers/patients were more likely to feel very comfortable with the intervention compared to the control group (65.9% vs. 48.0%, p=0.062).

B. Course Impact on Self-Reported Confidence Levels

For scenario 1, the median confidence level increased from 3 (“somewhat confident”) to 4 (“very confident”). For the subsequent scenarios, this increased from 2 (“a little confident”) to 3 (“somewhat confident”).

C. Self-Reported Learning Points –Evaluated via Course Feedback

1) Knowledge: The majority of students mentioned learning about the clinical management and discharge advice for gastroenteritis and urinary tract infection, and the need for procedural sedation in uncooperative young children. Students reported that they had learnt general frameworks and principles for communication, and concepts of consent-taking. Students also frequently mentioned “practical”, in terms of “practical knowledge” and “practical tips” for communication.

2) Attitude: Students mentioned that they learnt about the importance of empathy. They also reported important aspects of patient-centred care, such as understanding the parent’s or patient’s perspective to formulate a treatment plan together and ensuring mutual understanding via “checking back to ensure the parent truly understands” and “to have a closed loop at the end of each communication”.

3) Skills: On a broader perspective, students described that they had learnt “how to properly structure communication with a patient’s parents” and “how to better communicate with parents using the various strategies”. Almost all students reflected that they had learnt specific communication skills, particularly with regards to dealing with challenging situations such as “how to approach parents who may not be cooperative/willing to listen to you” and “how to address angry parents” as well as “how to address their concerns and manage their expectations”. Two students also mentioned that they may not have been exposed to similar scenarios in their daily work: “… handle scenarios which are often not taught within lectures.”

IV. DISCUSSION

Computer-based communication courses have shown to improve students’ self-efficacy in performing communication tasks and assessments of students’ perceptions and practice of communication skills (Kemper et al., 2008), which was also demonstrated in this study’s improvement in self-reported confidence levels. It is however, expected that most students would experience increased confidence immediately after receiving new information about an unfamiliar topic.

This study provides an example of how a course that is traditionally delivered face-to-face can be designed to be delivered online, utilising less time and manpower resources while providing standardised teaching instruction in an evidence-based manner.

The qualitative findings in this study have not been replicated elsewhere, and provide an interesting perspective to student course perception. Students gained practical knowledge which is not readily available in clinical clerkships due to patient case variability and gained insight into an applicable framework for future clinical communication encounters. It is possible that the interactive nature of the course increased student presence and participation, resulting in improved learning outcomes in this aspect (Ammenwerth et al., 2019). Empathy, an important professional skill not easily taught but reflected as a learning point, was likely acquired through non-verbal communication demonstrated in the videos. Although it is not guaranteed that self-reported knowledge, skills and attitudes will translate into practice, future e-learning communication courses can be designed as pre-course material for traditional role-play facilitators to enhance learning experiences.

This study’s use of patient feedback provides unique insight into applied learning. Interestingly, the control group fared better in the actions of checking with caregivers/patients about management plan agreement and providing caregivers/patients with a summary. As clerkships also provide opportunities to observe healthcare professionals conducting clinical communication, it is likely that the control group learnt these behaviours from real-life encounters. Caregivers/patients tended to feel more comfortable with the intervention group, which could be explained through unmeasurable, subtle behaviours that the group may have learnt from the course, such as empathy, attentiveness and appropriate body language. Although the use of standardised patients for comparing both groups might have shown different results, it is known that how learners behave in the classroom and with real patients when unobserved is often less reflective of true workplace behaviours (Malhotra et al., 2009).

This study is limited by small participant and patient feedback numbers. Culturally, many patients forget their healthcare providers and experiences. An ideal situation would be direct clinical encounter observation, but due to the Hawthorne effect, a less truthful version of student behaviour may be observed instead.

V. CONCLUSION

Although online video-based communication courses can be used as a standardised teaching tool to improve student self-reported confidence levels and self-perceived knowledge, skills and attitudes, it remains to be proven if they can result in a change in student behaviour. It is likely that on-the-job experiences also contribute to their ability to demonstrate effective communication, which supports the supplementation, rather than the replacement of such practical experiences with online video-based course material.

Notes on Contributors

CC, CL and TKC contributed to the conception and design of the work. CC, CL and TKC also analysed data and drafted the work . CC, CL and TKC approved the final published version and are agreeable to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CC, CL and TKC collectively contributed equally to this paper.

Ethical Approval

This study was exempted from formal Centralized Institutional Review Board review by the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2017/2178).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the SingHealth Paediatrics Academic Clinical Programme in providing the grant funding for this project.

Funding

The study was funded by the SingHealth Paediatrics Academic Clinical Programme Tan Cheng Lim Fund Grant which was awarded in 2017 (Grant Reference: PAEDACP-TCL/2017/EDU/001).

Declaration of Interest

All authors disclose that there are no potential conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that could have direct or potential influence or impart bias on the work.

References

Ammenwerth. E., Hackl, W. O., Dornauer, V., Felderer, M., Hoerbst, A., Nantschev, R., & Netzer, M. (2019). Impact of students’ presence and course participation on learning outcome in co-operative online-based courses. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 262, 87-90.

Kemper, K. J., Foy, J. M., Wissow, L., & Shore, S. (2008). Enhancing communication skills for paediatric visits through on-line training using video demonstrations. BMC Medical Education, 8, 8.

Makoul, G. (2001). Essential elements of communication in medical encounters: the Kalamazoo consensus statement. Academic Medicine, 76(4), 390-393.

Malhotra, A., Gregory, I., Darvill, E., Goble, E., Pryce-Roberts, A., Lundberg, K., & Hafstad, H. (2009). Mind the gap: Learners’ perspectives on what they learn in communication compared to how they and others behave in the real world. Patient Education and Counseling, 76(3), 385-90.

Zimmer, K. P., Solomon, B. S., Siberry, G. K., & Serwint, J. R. (2008). Continuity-structured clinical observations: assessing the multiple-observer evaluation in a pae1diatric resident continuity clinic. Pediatrics, 121(6), e1633-1645.

*Cristelle Chow

Department of Paediatrics,

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

100 Bukit Timah Road,

Singapore 229899

Email: cristelle.chow.ct@singhealth.com.sg

Published online: 5 May, TAPS 2020, 5(2), 41-44

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2020-5-2/SC2134

Sok Mui May Lim1,2, Zi An Galvyn Goh2 & Bhing Leet Tan1

1Health and Social Sciences Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD), Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore

Abstract

The use of standardised patients has become integral in the contemporary healthcare and medical education sector, with ongoing discussion on exploring ways to improve existing standardised patient programs. One potentially untapped group in society that may contribute to such programs are persons with disabilities. Persons with disabilities have journeyed through the healthcare system, from injury to post-rehabilitation, and can provide inputs based on their experiences beyond their conditions. This paper draws on our experiences gained from a two-phase experiential learning research project that involved occupational therapy students learning from persons with disabilities. This paper aims to provide eight highly feasible, systematic tips to involve persons with disabilities as standardised patients for assessments and practical lessons. We highlight the importance of considering persons with disabilities when they are in their role of standardised patients as paid co-workers rather than volunteers or patients. This partnership between persons with disabilities and educators should be viewed as a reciprocally beneficial one whereby the university and the disability community learn from one another.

Keywords: Standardised Patients, Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), Persons with Disabilities, Inclusion, Role-play, Script, Practical Lessons

I. INTRODUCTION

The use of standardised patients (SPs) has become integral to the contemporary healthcare and medical education sector. While an SP is commonly defined as a person trained to portray a scenario, an SP can also be an actual patient using his or her own history and physical exam findings (Kowitlawakul, Chow, Salam, & Ignacio, 2015). Presently, persons with disability (PWDs) have participated in SP programs, albeit less frequently and on a smaller scale (Long-Bellil et al., 2011; Minihan et al., 2004; Wells, Byron, McMullen, & Birchall, 2002). SPs with disabilities have also been used in Singapore hospitals, but mainly as patients to be examined for their own medical conditions. PWDs have a lot to offer in clinical education beyond sharing about their conditions.

A. Why Incorporate Persons with Disabilities into SP Programs?

There are many benefits in involving PWDs in SP programs. PWDs may be able to impart knowledge that ‘goes beyond the textbook’, due to their experiences of receiving services from various healthcare professionals – from the time the disability occurred to the post-rehabilitation phase of living independently in society. The input given based on their individual experiences would, therefore, be authentic (Wells et al., 2002). Students can get practice working with real PWDs in a safe setting where they can make mistakes and receive feedback before going for their clinical placements and meeting with real patients (Minihan et al., 2004). This can nurture a new generation of healthcare professionals who may be more proficient in treating PWDs, thereby raising the service delivery standard for the entire sector.

B. Perspectives Gained From Previous Experiential Learning Project

This paper is based on our experiences gained from a previous experiential learning research project. PWDs participated in a two-phase experiential learning research project that spanned two years (Lim, Tan, Lim, & Goh, 2018). In phase one, the PWDs acted as community teachers to occupational therapy student groups, interacting with them in the community while performing their daily activities. This paper draws from our experiences in Phase Two of the study, in which a group of PWDs were trained to and worked as SPs in practical classes and Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs). Upon the conclusion of the research project, PWDs continue to be part of the degree programme contributing as community teachers and SPs. The paper aims to provide practical helpful tips in bringing PWDs onboard as SPs.

II. DISCUSSION

A. Tip 1 – Interviewing and Selecting PWDs Who Are Suitable for Acting

PWDs were selected based on six criteria determined by faculty members in the health profession who have prior experience working with SPs. First, the PWD has an interest in healthcare education and wants to work with students for the purpose of educating them as future healthcare professionals. Second, the PWD should have come to terms and accepted their disability. It is very difficult for them to talk about their disability or role-play as a patient when they are still struggling emotionally with their own conditions. Third, the PWD does not have cognitive impairment and is able to understand and remember the script for role-playing. Fourth, he/she must be able to communicate clearly and coherently. Fifth, the PWD should be willing to learn the basics of acting or role-playing. Sixth, he/she must understand the objectives of the training or assessment, such as being impartial to all students and being honest in giving feedback when required.

B. Tip 2 – Training Should Be Conducted in Gradual Phases

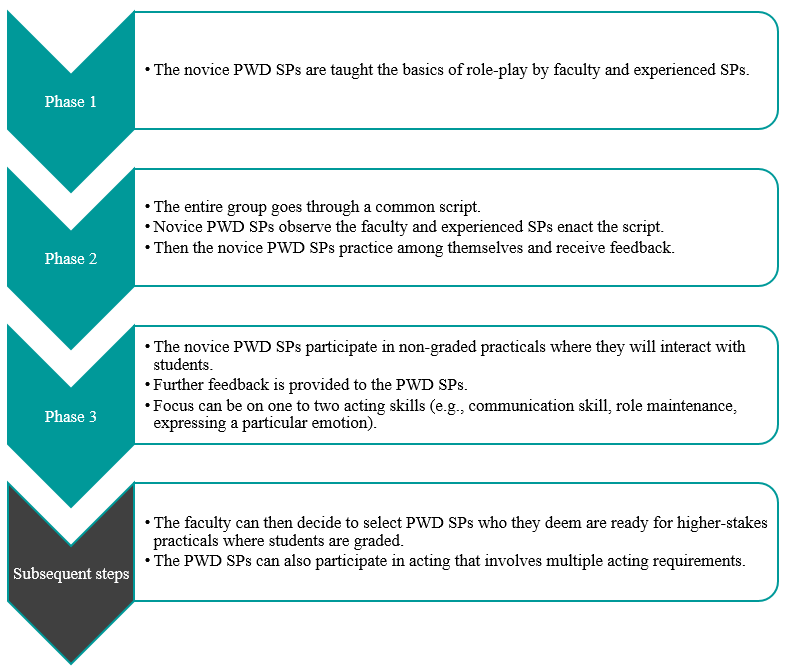

Training PWDs as SPs can be carried out in a gradual phase as outlined in details in Figure 1. In the first phase, novice PWD SPs are taught the basics of role-play by faculty and experienced SPs. In the second phase, the entire group goes through a common script. Novice PWD SPs observe the faculty and experienced SPs enact the script. Then, the novice PWD SPs practice amongst themselves and receive feedback.

After the training, faculty should speak to the PWDs individually to determine if they are comfortable with role-playing and address any queries that they may have. It is only after they attempt the role of an SP that they can personally assess their comfort level and confidence. This can ensure that the PWDs who participate are comfortable with their roles and feel engaged and respected by the institution.

In the third phase, PWD SPs can progress to non-graded practical lessons with students, which are less stressful for both students and PWD SPs. In subsequent phases, the faculty can then decide to select PWD SPs whom they deem are ready for summative assessments such as the OSCE.

C. Tip 3 – Start Novice PWD SPs with Simple and Suitable Scripts

Initial scripts should be simple and should not require complex acting skills. It takes time to gain confidence in memorising required lines, maintaining their roles as well as acting in scenarios which require more expression of emotions. Scripts that involve more sophisticated acting skills (e.g., maintenance of strong emotions) should be reserved for SPs who are experienced and confident with acting. The PWD SPs should be matched to suitable scripts that do not conflict with their disability. For example, a PWD SP who uses a wheelchair cannot be paired with a script that involves walking. The combination of progressing gradually and usage of suitable scripts allows for PWD SPs to refine their skills and ensure that their acting skills do not compromise the students’ learning experience.

D. Tip 4 – Prepare Students Not to Be Surprised By Real Disability

Prior to the interaction session, students should be pre-empted by the faculty that they would be working with PWDs who may have a range of disabilities. This is to prevent unnecessary surprise. In addition, students should be reminded that the disability may or may not be the focus of the scenario, depending on the instruction given to the student. For example, in an OSCE scenario, students may be tasked to explain a medical error or demonstrate a procedural skill instead of addressing the disability of the SP. This pre-empting can be complemented with teaching communication skills geared towards interacting with PWDs.

E. Tip 5 – Checking Accessibility – Within and Outside of the Venue

Ensuring accessibility prior to the session is important. This includes the route from the nearest public transport node (e.g., train station) to the venue. Things to take note of are the availability of ramps and lifts for wheelchair users and the presence of accessible parking lots. In addition, the venue where the lesson or assessment is going to take place needs to be inspected to ensure that the entrances and exits are wide enough for wheelchairs access.

Figure 1. Diagram to outline general recommended steps for training PWD SPs

F. Tip 6 – Pay PWDs at Market Rates and Accord Them Identical Contractual Rights

PWD SPs should be remunerated at market rates that are equal to SPs without disability. They also sign the same SP contract and fulfil the same legal obligations. In performing the role of the SP, they are treated as co-workers of the university, not volunteers or patients. This reflects the principles of equality and diversity, as well as the seriousness of their roles as active members of the healthcare and medical education system. If there are certain risks involved in their interaction with students, such risks should be made clear to the PWD SPs, so they can make an informed decision on accepting the job.

G. Tip 7 – Provide Opportunity for PWDs to Give Feedback

PWDs can be a valuable resource in providing feedback to faculty, scenario developers and other SPs. Similarly, they may be able to give insightful feedback to students. It is important to train the PWD SPs on the methods of providing feedback to students. Given their lived experience, they can provide insight into how real patients would respond and react while suggesting ways for trainee healthcare professionals to respond in a more patient-centred manner.

H. Tip 8 – Reflect and Improve

Carrying out an evaluation with the respective stakeholders, whether they are PWD SPs, faculty, or students, is key to the success of an inclusive SP program. This can also ensure quality assurance of the program. The following are several broad questions which can be considered in the evaluation. Firstly, whether the stakeholder faced any challenges during the session. Secondly, whether the scenarios or scripts worked well for PWD SPs to interact with students. Thirdly, whether there are any other ways that the learning experience can be improved. This can provide rich data for the SP program developers to reflect and improve upon the pedagogy. We have received positive feedback from both students and PWDs in this project.

III. CONCLUSION

It is important to empower PWDs and create a dynamic relationship between them and healthcare professionals/

educators. For an inclusive SP program to be effective, educators must change their own mindset about PWDs. We have to switch the lens from viewing them as patients to co-workers. This partnership should be viewed as a reciprocally beneficial one whereby the university and the disability community learn from one another. Through the process of engagement, both educators and students learn from PWD SPs about knowledge that goes beyond the textbook, and the factors that enhance or diminish the quality of healthcare/medical service delivery from individuals who have experienced going through the healthcare/medical system. With time and with more training institutions engaging PWDs as SPs, this can be a potentially viable employment option for PWDs.

Notes on Contributors

Associate Professor May Lim is the Director of the Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD) at the Singapore Institute of Technology, and a faculty in the Health and Social Sciences Cluster teaching occupational therapy.

At the time when this work was done, Mr Goh Zi An Galvyn was a research assistant in the Centre for Learning Environment and Assessment Development (CoLEAD) at the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Associate Professor Tan Bhing Leet is the Deputy Cluster Director (Applied Learning) of the Health and Social Sciences Cluster, and Programme Director of the Bachelor of Science in Occupational Therapy degree programme at the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Singapore Institute of Technology Institutional Review Board for this project (IRB number: 20150002).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all faculty, students, PWD and non-PWD standardised patients who were involved in the Singapore Institute of Technology Bachelor of Science in Occupational Therapy degree programme. In addition, we would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Associate Professor Tham Kum Ying, Education Director of Tan Tock Seng Hospital Pre-Professional Education Office and senior lecturers Miss Heidi Tan and Mr Lim Hua Beng from the Singapore Institute of Technology.

Funding

Funding was provided from the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE Tertiary Education Research Fund grant: R-MOE-A203-A002).

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest concerning any aspect of this research.

References

Kowitlawakul, Y., Chow, Y., Salam, Z., & Ignacio, J. (2015). Exploring the use of standardized patients for simulation-based learning in preparing advanced practice nurses. Nurse Education Today, 35(7), 894-899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.03.004

Lim, S. M., Tan, B. L., Lim, H. B., & Goh, Z. A. G. (2018). Engaging persons with disabilities as community teachers for experiential learning in occupational therapy education. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(1), 36-45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1569186118783877

Long-Bellil, L. M., Robey, K. L., Graham, C. L., Minihan, P. M., Smeltzer, S. C., Kahn, P., & Alliance for Disability in Health Care Education. (2011). Teaching medical students about disability: The use of standardized patients. Academic Medicine, 86(9), 1163-1170. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b5dc

Minihan, P. M., Bradshaw, Y. S., Long, L. M., Altman, W., Perduta-Fulginiti, S., Ector, J., … Sneirson, R. (2004). Teaching about disability: Involving patients with disabilities as medical educators. Disability Studies Quarterly, 24(4). https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v24i4.883

Wells, T. P. E., Byron, M. A., McMullen, S. H. P., & Birchall, M. A. (2002). Disability teaching for medical students: Disabled people contribute to curriculum development. Medical Education, 36(8), 788-790. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01264_1.x

*Lim Sok Mui

Singapore Institute of Technology,

SIT@Dover, 10 Dover Drive,

Singapore 138683

Email: may.lim@singaporetech.edu.sg

Published online: 1 June, TAPS 2016, 1(1), 23-25

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2016-1-1/SC1009

Richard Hays

University of Tasmania, Australia

Abstract

A curriculum is an important component of a medical program because it is the source of information that learners, teachers and external stakeholders use to understand what learners will experience on their journey to recognition as a medical graduate. While many focus on and debate the content of a medical curriculum, with some suggestions that there should be national curricula for each jurisdiction or even a global curriculum for all medical programs, the curriculum content is only one factor to consider when designing, revising or accrediting a curriculum. Just as important are the alignment with the program’s mission and health workforce needs, the presence of agreed graduate outcomes, the theoretical bases of the curriculum, the prior learning of commencing students, the curriculum implementation models, the assessment of student progress and program evaluation processes. This paper presents a framework for this more holistic approach to reviewing a curriculum, proposing triangulation of information from several sources – documents, websites, learners, teachers and employers – and considering several accreditation standards that impact on curriculum design and delivery.

Keywords: Curriculum design; curriculum review; accreditation; social accountability; program evaluation

I. BACKGROUND

In medical education the curriculum defines medical programs, guides the teaching by faculty and informs the learning by students of what is required to become a doctor. For basic medical education, the outcome is recognition as a novice practitioner, and for subsequent levels there are more specific outcomes related to particular specialties. The term ‘curriculum’ is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as ‘the subjects comprising a course of study in a school or college’, which suggests an emphasis on the content, whereas learning may depend significantly on how the content is delivered, learned and assessed.

The pace of medical curriculum review has increased globally due to several factors. Several new medical programs have been established, based on growing populations and rising health care standards, particularly in developing nations. Whether purchased from existing institutions or developed locally, new curricula have to be designed and most new programs face either mandatory or voluntary accreditation processes. Demographics are changing, particularly in developed nations, where the population is ageing and living with increasingly complex and chronic health care needs, requiring a larger and differently trained medical workforce (Duckett, 2005). Many universities are seeking efficiencies in program delivery, because the small group, clinician-led models preferred in medical education are expensive; leaders ask, perhaps not unreasonably, why medical education cannot be provided as effectively by less expensive methods, such as large group lectures supported by on-line resources and more junior faculty. We find ourselves in what might be termed a ‘post-PBL’ environment, where PBL programs have been criticised for gaps or lack of depth in anatomy, pathology and other foundation sciences, even though PBL models were developed in part to address the rapid increase in the knowledge base for medical practice, promoting peer-supported and self-directed learning (Dolmans et al, 2005). Can coping with this knowledge explosion be done differently?

Employers find that some medical graduates are not yet ‘work ready’, able to take responsibility for their actions or contribute to safe patient care without (ex-pensive) supervision and further training. Finally, regulators are becoming more vocal about challenges to the commonly used self-regulation model for the medical profession, amidst increasing complaints and concerns about competence and errors. Although most of these concerns relate to communication skills and professional behaviours of a small minority, regulators are increasing requirements for standards to be met by medical graduates outside of the traditional scientific knowledge domains. As a result, there are increasing requirements for accreditation or formal recognition of medical programs by regulatory authorities to ensure that programs produce the graduates needed to provide medical care. Arguably, the strongest accreditation systems are conducted by the General Medical Council for the UK, the Australian Medical Council for Australia and New Zealand, and the Liaison Committee for Medical Education (USA and Canada), but many other jurisdictions have, or are developing, strong accreditation processes. There are also global standards developed and promoted by the World Federation of Medical Education (WFME), which map reasonably well to most standards. While the World Federation of Medical Education is not an accrediting body, there are moves to mandate that accreditation standards and processes must comply with the WFME global standards for graduates to be eligible for recognition across jurisdictional borders (Karle, 2006).

There are therefore two broad categories of curriculum review. The first is that conducted by medical schools, new and old, to develop, maintain or refresh curricula that are current and fit for purpose. This should be a continuous process, with changes based on some kind of evidence, ideally evaluation data. The second category is that conducted by regulatory bodies during accreditation processes, in which the curriculum is always a major focus. For both categories, a broader, more holistic view of a curriculum, rather than just content, should be adopted. This means that a curriculum review should seek information or data from much more than just descriptions of the subject content. This paper presents a framework for achieving this more holistic approach.

II. METHOD

This paper is based on an analysis of the structure of standards and accreditation protocols of the General Medical Council, the Australian Medical Council, the Liaison Committee for Medical Education and the World Federation for Medical Education. In each case medical programs are measured against several standards, where only one standard might specifically address curriculum content, but other standards address delivery, assessment and evaluation. Sources of evidence for a curriculum review may therefore be found when considering almost all standards.

A. A framework for reviewing a medical curriculum

Although a curriculum should be well described in writing, such documents are a single source of information about what is intended. Judgements about curriculum content and process are best made through triangulation of information and data from a combination of potential sources that reflect a wide range of issues, as summarised in Table 1. Most of these sources should be readily accessible, although requires both electronic access (through a guest log in account) and a physical visit to inspect the facilities. Further information, particularly about implementation, can be obtained through observation of aspects of program delivery, such as teaching sessions and clinical examinations.

Constructive alignment of a curriculum, from the vision and mission through curriculum delivery and assessment, is important because it demonstrates that the curriculum is a more holistic, ‘connected’ entity. It shows that curriculum content, process and intended outcomes are planned and designed with an explicit intention to produce a particular kind of graduate. Ideally, the outcomes are the same as those of the accreditation body, although many schools will add some of their own. For example, while all schools in a particular jurisdiction may plan to produce ‘work ready’ graduates safe to enter postgraduate training, some may have additional outcomes relating to elite research performance or to meeting the needs of underserved populations, following the growing international trend towards social accountability (Boelen and Woollard, 2009).

There should be evidence of purposeful, theory-based educational design (Prideaux, 2003). There is a spectrum of pedagogical models, from separate subjects delivered to large groups by lectures, through to highly integrated (vertically and horizontally) programs delivered through interactive, small groups, following a case-based or problem-based learning model. While educators may have a preference for a particular model, all can work, so long as the content, delivery and assessment methods are done well. It is important to design the curriculum content and process to match the learners’ characteristics at entry. For example, school leaver programs tend to be longer and to have adjustment to university life and introductory foundation sciences early, followed by more integrated, clinically-immersed learning, whereas graduate entry programs commence with an assumption that students are ready to commence with the more integrated, clinically-oriented approach.

An additional consideration is cohort size, because interactive, small group models are difficult to deliver unless group size is appropriate (8-10 maximum?). This has implications for the physical facilities and intranet-based Learning Management System (LMS), because small group, interactive learning required larger numbers of tutorial rooms that are appropriately furnished and equipped, and accessible, flexible and interactive repositories of electronic learning resources.

Ideally, all learning outcomes are measurable – this may be a matter of wording – and then form the basis of assessment practices, such as method selection, blueprinting, item bank development and standard setting. It is important that an integrated curriculum has integrated assessment, otherwise students may focus on non-integrated sources (a ‘hidden curriculum’) rather than the curriculum. Finally, there should be evidence of evaluation processes that monitor the curriculum content and delivery. A medical curriculum should be a continuously evolving entity, with decisions for change based on the best available evidence. Such evidence may come from both the routine, annual or semester-based program-wide data on participation, and the more reflexive and exploration of specific questions or concerns that arise during academic years. There should be evidence of evaluation feedback being formally considered, with decisions to make changes and then evidence that the change has taken place and participants advised of the results of the evaluation.

|

Curriculum feature |

Information | sources | ||||||

|

Website /LMS |

Program outline | Unit/subject outlines | Assessment reports* | Faculty | Students* | Stakeholders |

Facilities Tour |

|

| Aligned with Vision & Mission | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Measurable graduate outcomes | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Purposeful design | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Appropriate for admission point | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Suitability of facilities and LMS | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Aligned with assessment | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Evaluation explicit and built-in | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Table 1. Framework for reviewing a medical curriculum

Table 1 includes the potential sources of information that should be sought when a curriculum is reviewed. This demonstrates the potential weakness of reviews based on only documents, because the documents describe what is intended to take place, not necessarily what does take place. Hence speaking with faculty (including part-time clinical teachers), students, employers and regulators can provide different information that describes the curriculum-in-action. Also important is the direct observation of teaching sessions of various types and of clinical assessment, both in the workplace and in OSCEs. It is not unusual for application to vary widely due to local ‘modifications’, despite apparently similar, ‘standard’ descriptions.

III. CONCLUSION

Reviewing a curriculum should be a continuous activity to maintain currency and fitness for purpose. The review should adopt a more holistic approach that includes curriculum content, delivery and assessment practices, as well as resourcing. This paper presents a framework to guide curriculum reviewers the issues to consider and the potential sources of information on which to base judgements.

Notes on Contributors

Richard Hays is an experienced medical educator with qualifications in both medicine and education. He has contributed to or led the design of several medical education programs and has also conducted formal medical program reviews at approximately 20 institutions in the United Kingdom, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval is not sought because there is no data presented and no possibility of identification of individual patients or students.

Declaration of Interest

There is no conflict of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

Boelen, C. & Woollard, R. (2009). Social accountability and accreditation: a new frontier for educational institutions. Medical Education, 43, 887-894.

Dolmans, D., De Grave, W., Wolfhagen I. & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2005). Problem-based learning: future challenges for educational practice and research. Medical Education, 39, 732-741.

Duckett, S. (2005). Health workforce design for the 21st century. Australian Health Review Quarterly, 29, 201-210.

Karle, H. (2006). Global standards and Accreditation in medical education: a view from the WFME. Academic Medicine, 81, S43-S48.

Prideaux, D. (2003). ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Curriculum design. British Medical Journal, 326, 268-270.

Published online: 1 June, TAPS 2016, 1(1), 20-22

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2016-1-1/SC1011

Fong Jie Ming Nigel1*, Gan Ming Jin Eugene1*, Lim Yan Zheng Daniel1*, Ngiam Jing Hao Nicholas1*, Yeung Lok Kin Wesley1* & Tay Sook Muay2

1Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Department of Anaesthesia, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

* Joint first authors

Abstract

The surgical physical examination is a fundamental part of medical training. We describe our experience with a near-peer teaching program for surgical physical examination skills, which involved senior medical students tutoring junior students starting their clinical rotations. We assessed scores on an Objective Structured Clinical Examination of the abdominal, vascular, and lumps examination before and after teaching. There was improvement in scores for all examinations and overall positive feedback from all students. This suggests that near-peer teaching may be a useful adjunct to faculty-led teaching of clinical skills.

Keywords: Near Peer Teaching; Physical Examination; Surgery

I. INTRODUCTION

Bedside clinical examination is fundamental to the practice of medicine. All 2nd year medical students at the National University of Singapore (NUS) undergo a 1 month Clinical Skills Foundation Course at the end of the academic year. This course is their maiden clinical posting and aims to introduce fundamentals of history taking and physical examination before they transit to their clinical years (3rd to 5th year). Unfortunately, it is challenging for faculty to effectively impart these skills due to increasing student numbers, busy clinical workloads and time constraints, leading to inadequate opportunities for learners’ active participation (versus passive observation), providing feedback, reflection and discussion (Spencer, 2003).

Near-peer teaching (NPT), using senior students to teach juniors, may supplement faculty-led teaching and ameliorate these difficulties. It has shown success in both case-based learning and teaching physical clinical examination (Blank et al, 2013). Beyond circumventing faculty constraints, NPT may promote a greater degree of active learning, knowledge application, and opportunities to correct misconceptions. Near-peer tutors may better understand learner challenges and share personal experience in overcoming these challenges (cognitive congruence), and promote a conducive, collaborative learning environment (social congruence) (Lockspeiser et al, 2008). Tutors who become role models may also benefit from deeper learning of content (Ten Cate et al, 2007) coupled with the development of higher cognitive skills whilst tutoring – to teach is to learn twice!

We describe a NPT initiative to teach surgical physical examination skills to students who are encountering clinical patients for the first time, in the ward via (i) a practical examination skills workshop and, (ii) the use of a novel course-book developed by the near-peer tutors as a teaching aid.

II. METHODS

Forty second-year students undergoing their maiden clinical posting at the Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, participated in a one-day workshop with IRB approval and written consent (Singhealth Centralised IRB Exemption 2015/2248, 27 March 2015). Students were divided into three groups and participated in three 2-hour long physical examination stations in a round-robin format. The stations were – (1) Abdominal examination, (2) Peripheral vascular examination, and (3) Lumps (skin, neck, breast, and groin). Five final-year students planned the workshop and served as near-peer tutors. A course book that served as a learning aid was written by near-peer tutors and vetted by faculty members. It was designed with the goal of encouraging the student to move beyond knowledge acquisition to application and synthesis of knowledge. Each section of the book introduced the sequence and rationale behind the steps of each surgical physical examination via a series of questions. These questions aimed to facilitate: (1) Understanding of the clinical significance and relationship between examination findings, (2) Clinico-pathological correlation and (3) Reasoning from first principles.

Instruction was modelled on Peyton’s four-step approach. Near-peer tutors explained the background to each examination, demonstrated the examination steps once, and discussed the technique, rationale, and possible findings in each step. Students then practiced on each other under supervision. To consolidate learning, near-peer tutors conducted post-tests based on objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) templates provided by the National University of Singapore, and provided qualitative feedback. Students also undertook identical OSCE pre-tests for comparison, and voluntarily completed anonymous feedback forms that made use of a 5-point Likert scale (Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree) to evaluate various aspects of the workshop.

Statistical analysis was performed in R. Test scores were percentages of maximum possible score. Paired differences between individual pre-test and post-test scores were analyzed using Bayesian Estimation on weakly informative normal priors. Posterior probability distributions were approximated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo with 100,000 resamples.

III. RESULTS

| Exam | Mean pre-test score, out of 100 | Mean post-test score, out of 100 | Mean Paired Difference, absolute (95% credible interval) |

| Abdomen (n=40) | 73.3 | 91.4 | + 17.3 (10.0 – 24.6) |

| Arterial (n=40) | 41.6 | 91.3 | + 49.7 (41.7 – 57.8) |

| Lumps (n=38)* | 55.7 | 90.3 | + 34.7 (27.6 – 41.5) |

Table 1. Summary of pre-test and post-test results, and paired difference indicating the improvement from pre- to post-test

*Two students had to leave early

OSCE scores improved after teaching (Table 1), most markedly in the arterial examination (+49.7, credible interval 41.7-57.8), and also in the lumps (+34.7, credible interval 27.6-41.5) and abdominal examination (+17.3, credible interval 10.0-24.6). The abdominal examination started with the highest mean pre-test scores (73.3%), compared to the arterial (41.6%) and lumps examinations (55.7%). This may reflect greater exposure to the abdominal examination during prior faculty-led tutorials.

Out of the thirty-four students who provided feedback. 33 (97%) students agreed that the workshop helped them to pick up basic physical examination skills, and 32 (94%) were now more confident in performing these examinations on a real patient. Notably, all 34 students (100%) described better understanding of the rationale behind each clinical examination step, as opposed to performing the examinations mechanically; all (100%) found the small-group format conducive for learning. While all (100%) would encourage their juniors to attend this workshop next year, only 12 (35%) expressed interest to be a mentor themselves.

IV. DISCUSSION

We describe a student-initiated NPT initiative that supplements a faculty-led two-week surgical clinical rotation and physical examination teaching for students commencing their maiden clinical posting. This initiative has benefits to both students and near-peer tutors.

With regards to students, this initiative improved OSCE scores and was well received. The marked improvement in OSCE scores in areas less well-covered during faculty-led tutorials suggests that NPT sessions focusing on these gaps may complement and augment faculty-led tutorials particularly well. Physical examination stations with poorer OSCE scores may also highlight and objectively reflect areas in curriculum where faculty should focus on and refine. While it is encouraging that a number of students were keen to be mentors in the future, we are unsure as to why this aspiration was not a unanimous one amongst the entire student group. Possible reasons may include a lack of familiarity with the expectations of clinical teaching and lack of confidence given that this is their maiden clinical exposure.

Although the benefits to near-peer tutors were not formally evaluated, we propose that preparation of the course book and execution of the workshop required them to revisit their pre-clinical knowledge, understand its application to their current clinical knowledge, and synthesize and crystalize all the information to present it effectively, thus reinforcing their own learning.

With regards to the use of teaching aids, near-peer tutor developed examination revision notes for final year students accompanying NPT has been described (Rashid et al, 2011). Our course book, however, is a unique intervention that is primarily aimed at facilitating the building of links between pre-clinical knowledge and first clinical exposure. Future evaluation is necessary to determine the objective benefits of such a teaching aid.

Study limitations include a small sample size, potential observer bias because workshop tutors were OSCE assessors, and the lack of a comparison arm (e.g. Faculty teaching). These limitations can be addressed in the future by: Increasing our sample size by gradually extending subsequent editions of the workshop to all local teaching hospitals, recruiting more near-peers to serve as independent assessors to eliminate observe bias, and designing a study to compare faculty teaching alone against NPT in addition to faculty teaching.

We hope to highlight this valuable, yet under-utilized teaching modality which may be uniquely valuable in addressing the challenges faced in teaching clinical skills. We are optimistic that future studies may detail its academic, non-academic, and logistical benefits to students, near-peer tutors and faculty members alike.

Notes on Contributors

Fong Jie Ming Nigel, Gan Ming Jin Eugene, Lim Yan Zheng Daniel, Ngiam Jing Hao Nicholas and Yeung Lok Kin Wesley are final year medical students at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine. They have an interest in medical education and have been involved in coordinating and implementing various near-peer teaching efforts in medical school. They conceived this initiative and were responsible for its implementation and preparation for publication.

Associate Professor Tay Sook Muay is a senior consultant anesthesiologist at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH), and the current Associate Dean for NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, SGH Campus. She is highly active in local and international teaching programs, education meetings and pedagogical committees. She is the faculty mentor for this near-peer teaching initiative.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge Cheng Kam Fei, Melissa Tang, and Krissie Chin from the Singapore General Hospital Associate Dean’s Office, for logistical support for the program.

Declaration of Interest

This is an unfunded study. All authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Blank, W. A., Blankenfeld, H., Vogelmann, R., Linde, K., & Schneider, A. (2013). Can near-peer medical students effectively teach a new curriculum in physical examination? BMC Med Educ, 13, 165.

Lockspeiser, T. M., O’Sullivan, P., Teherani, A. & Muller, J. (2008). Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 13(3), 361-72.

Rashid, M. S., Sobowale, O., & Gore, D. (2011). A near-peer teaching program designed, developed and delivered exclusively by recent medical graduates for final year medical students sitting the final objective structured clinical examination (OSCE). BMC Med Educ, 11, 11.

Spencer, J. (2003). Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. BMJ, 326(7389), 591-4.

Ten Cate, O., & Durning, S. (2007). Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach, 29(6), 591-9.

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore

1E Kent Ridge Road,

NUHS Tower Block, Level 11, Singapore 119228

Tel: 67723737

Email: nigelfong@gmail.com

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2017, 2(1), 25-28

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2017-2-1/SC1001

Dipanshi Patel1, Namrata Baxi2, Abhishek Agarwal2, Kenyetta Givans1, Krystal Hunter2, Vijay Rajput3 & Anuradha Mookerjee2

1Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey, United States of America; 2Cooper University Hospital, Camden, New Jersey, United States of America; 3Ross University School of Medicine, Miramar, Florida, United States of America

Abstract

Introduction: In graduate medical education, trainees have different academic and professional growth needs throughout their career, but these needs have not been well studied (Gusic, Zenni, Ludwig & First, 2010). Traditional mentoring programs in many disciplines including medicine, science, law, business and education report individuals with mentors having higher earnings, higher job satisfaction and higher rates of promotion, compared to individuals without mentors (Bussey-Jones et al.,2006; Sambunak, Straus & Marusic, 2010).

Methods: We developed a structured mentoring program in the Department of Medicine in Cooper University Hospital which encourages both academic and professional growth through a major emphasis on academic scholarship. We created a 21 questions survey to evaluate mentee satisfaction towards their assigned mentors. The questions fit into four categories consisting of the mentor’s personal attributes and action characteristics and mentee’s short term and long term career goals. Sixty junior trainees (Post Graduate Year 1-3) and 39 senior trainees (Post Graduate Year 4-7) completed the survey.

Results and Conclusions: Senior trainees were more satisfied with their mentors’ intrinsic qualities (96%) compared to junior trainees (93%), c2 (1, N=980) = 5.72, p=0.017. Additionally, senior trainees were more satisfied with their mentors’ action characteristics (95%) compared to junior trainees (91%), c2(1, N=677) = 4.03, p=0.045. Junior trainees had a lower satisfaction rating, compared to their senior colleagues, which might imply that their needs and desires were not properly addressed by their mentors. Both junior and senior trainees identified the lowest satisfaction rates in their mentors’ communication skills and ability to challenge them. This was an area of weakness within the mentorship program which requires further research and attention.

Keywords: Mentoring; Graduate Medical Education; Assessment

Practice Highlights

- Traditional mentoring programs in many disciplines including medicine, science, law, business, and education report mentees having higher earnings, higher job satisfaction and higher rates of promotion, compared to individuals without mentors (Bussey-Jones et al., 2006; Sambunak et al., 2010).

- There have been many variations to the mentorship framework, but there is a lack in scientific evidence to conclude which aspects of such a program holds the most beneficial characteristics (Bussey-Jones et al., 2006; Gusic et al., 2010).

- The professional and personal development needs for trainees change as they progress in their medical training.

- There is need for faculty development to enhance communication skills between mentor and mentee.

I. INTRODUCTION

Mentoring is an integral part of academic medicine and professional development during graduate medical education (Sambunak et al., 2010). Traditional mentoring programs in many disciplines including medicine, science, law, business, and education report individuals with mentors having higher earnings, higher job satisfaction and higher rates of promotion, compared to individuals without mentors (Bussey-Jones et al., 2006; Sambunak et al., 2010). Unfortunately, mentoring in academic medicine is often undervalued and not well studied (Sambunjak et al., 2006). Additionally, while many trainees and faculty form mentoring relationships independently, there is a lack of formal mentoring of postgraduate trainees in medicine (Sambunjak et al., 2006).