General dental practitioners’ perceptions on Team-based learning pedagogy for continuing dental education

Submitted: 14 April 2021

Accepted: 24 June 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 98-101

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/SC2517

Lean Heong Foo & Marianne Meng Ann Ong

Department of Restorative Dentistry, National Dental Centre Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Team-based learning (TBL) pedagogy is a structured, flipped classroom approach to promote active learning. In April 2019, we designed a TBL workshop to introduce the New Classification of Periodontal Diseases 2017 to a group of general dental practitioners (GDPs). We aimed to investigate GDPs feedback on learning this new classification using TBL pedagogy.

Methods: Two articles related to the 2017 classification were sent to 22 GDPs 2 weeks prior to a 3-hour workshop. During the face-to-face session, they were randomly assigned to five groups. They participated in individual and group readiness assurance tests. Subsequently, the GDPs had inter- and intragroup facilitated discussions on three simulated clinical cases. They then provided feedback using a pen-to-paper survey. Based on a 5-point Likert scale (1-strongly disagree to 5-strongly agree), they indicated their level of agreement on items related to the workshop and their learning experience.

Results: Majority (94.7%, 18 out of 19 GDPs) agreed the session improved their understanding of the new classification and they preferred this TBL pedagogy compared to a conventional lecture. All learners agreed they can apply the knowledge to their work and there was a high degree of participation and involvement during the session. They found the group discussion and the simulated clinical cases useful.

Conclusion: A TBL workshop is suitable for clinical teaching of the New Classification of Periodontal Diseases 2017 for GDPs. Its structure promotes interaction among learners with the opportunity to provide feedback and reflection during the group discussions. This model might be a good pedagogy for continuing dental education.

Keywords: Team-based Learning, General Dental Practitioners, New Classification of Periodontal Diseases

I. INTRODUCTION

Team-based learning (TBL) is a flipped classroom, structured learning pedagogy that was introduced by Larry Michaelsen and has gained popularity among healthcare educators recently. TBL is learner-centric and dialectic based, and practices logical discussion used for determining the truth of a theory or opinion (Michaelsen et al., 2008). It provides the opportunity for peer-teaching by group members and can assist weaker students in understanding course materials.

Several dental educators have utilised TBL in undergraduate dentistry programmes and observed higher engagement among learners, less student contact time and faculty time, and higher course grades (Haj-Ali & Al Quran, 2013). General dental practitioners (GDPs), unlike undergraduate dental students, juggle between busy dental practice and family life. Hence, GDPs might seek active learning with direct knowledge application to manage their continuing dental education needs efficiently. The World Workshop of Periodontology recently revamped the diagnosis of periodontal diseases and proposed a new classification of staging (Stage I-IV; based on severity of disease) and grading (Grade A-C; based on disease progression) for periodontitis (Tonetti et al., 2018). We aimed to investigate GDP feedback on learning this new classification using TBL pedagogy.

II. METHODS

This is a descriptive study on GDPs’ feedback on learning the New Classification of Periodontal Diseases 2017 using a TBL approach. 22 GDPs attended the TBL workshop in April 2019.

Two articles related to the new classification were sent to the GDPs 2 weeks prior to the 3-hour workshop. Five multiple-choice questions were crafted from the two articles (Individual Readiness Assurance Test, IRAT) to assess learners’ basic understanding of the new classification. Learners were divided into five groups to discuss IRAT and provide answers using the immediate feedback assessment technique card (Group Readiness Assurance Test, GRAT). Faculty then highlighted key elements of the new classification. Three clinical periodontal cases crafted based on the 4S framework principles i.e. same problem, significant problem, specific choice, and simultaneous reporting, were used in the application process (Michaelsen et al., 2008). The key question was to diagnose the periodontal condition based on the staging and grading criteria. Lastly, learners provided implied consent by answering an anonymous pen-to-paper survey voluntarily. They answered based on their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (5 indicating strongly agree, 1 indicating strongly disagree). The survey comprising 13 education-related statements: two statements related to programme content, two to presentation, six to learning experience, and three about the workshop. Three qualitative questions in the survey were: “What do you like most about the workshop?”, “What aspects of the session could be improved?” and “Other comments and feedback”.

III. RESULTS

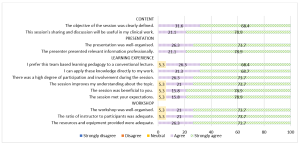

Nineteen out of the 22 GDPs who attended the TBL workshop responded to the survey (response rate 86.4%). Results are summarised in Figure 1. We conducted a reliability analysis on the perceived task values scale comprising two subscales (learning experience and workshop) with at least three items.

Figure 1. Learners’ feedback about the workshop

A. Content (Two items)

During the workshop, we highlighted the staging and grading criteria for the new classification. Learners provided a mean score of 4.74 (standard deviation, SD, 0.446; median 5) in two statements related to content. In general, 68.4% of them strongly agreed and 31.6% agreed the objective of the workshop was clearly defined. There were 78.9% and 21.1% of learners who strongly agreed and agreed respectively that the sharing and discussion during the workshop was useful to their clinical work.

B. Presentation (Two items)

Learners gave a mean score of 4.76 for presentation (SD 0.431; median 5). There were 73.7% learners who strongly agreed and 26.3% who agreed that the presentation was well-organised. In addition, 78.9% and 21.1% of the learners strongly agreed and agreed respectively that the presenter presented relevant information professionally.

C. Learning Experience (Six items)

Cronbach’s alpha for the learning experience subscale reached acceptable reliability at α = 0.81. The mean score for learning experience was 4.70 (SD 0.531; median 5). There were 68.4% learners who strongly agreed and 26.3% who agreed that they prefer TBL pedagogy to a conventional lecture. Also, 68.7% of the learners strongly agreed and 31.3% agreed they could apply the knowledge directly to their work. All learners agreed that there was a high degree of participation and involvement during the session. 18 learners (94.7%) agreed that the session met their expectations and improved their understanding about the topic.

D. Workshop (Three items)

The mean score for learners’ feedback on the workshop was 4.71 (SD 0.533; median 5). 18 learners (94.7%) agreed that the workshop was well organised with an adequate ratio of instructor to participants (2:22). There were 73.7% learners who strongly agreed and 26.3% who agreed that resources and equipment provided were adequate. Cronbach’s alpha for the workshop subscale reached acceptable reliability at α = 0.75.

E. Qualitative Feedback

The learners cited the following themes as their favourite component of the workshop: “group interaction and discussion” (4), “clinical case discussion” (3), “useful and relevant clinical cases” (1), “interesting readiness assurance test” (1), and “pre-reading material” (1). They also cited “active learning” (1), “correct wrong understanding” (1), “discussion improves my understanding” (1), and “great information and lecturer” (1) as positive learning experiences. Three different learners provided feedback of “best workshop ever attended”, “well done”, and “very good” respectively. One learner commented that the air-conditioning in the room was cold. One learner commented on small font size in dental charting and another learner suggested “less tests at the start”.

IV. DISCUSSION

The flipped classroom concept in TBL was suitable for GDPs to study the pre-reading articles at their own pace. The structured workshop enabled them to correct any misconception immediately and deepen their understanding about the new classification. This observation concurs with the finding that all GDPs agreed they could apply the knowledge to their work and preferred this pedagogy over a traditional lecture. This active learning process differs from a conventional didactic lecture, which is faculty-centric with less feedback and interaction. Hence, this pedagogy can be applied for some continuing dental education programmes by improving the delivery and application of new concepts. The 4S framework in the application cases are key elements to promote productive and logical discussion similar to a debate facilitated by faculty. The problem-solving aspect of TBL, along with the scaffolding and guidance by faculty, can enhance the metacognition process among learners (Hrynchak & Batty, 2012). Almost all learners agreed there was an adequate ratio of faculty to participants, emphasising the benefit of using TBL workshops to teach a large group of learners with less faculty. However, faculty needs to work more in planning and preparing the teaching materials, executing, and facilitating the session following the TBL structure and process. In addition, hurdles in conducting TBL include acceptance from faculty and learners, difficulty in supervising a large group, the customisation of the course content, and adequate training and expertise to conduct TBL effectively.

The learners also cited “group interaction and discussion” as their favourite component of the workshop. The learning theory underpinning TBL is the constructivist learning theory where the faculty exposes knowledge inconsistency during group discussion, subsequently allowing a new mental framework to be built upon the new understanding (Hrynchak & Batty, 2012). TBL is useful in healthcare education since it can promote good critical thinking and teamwork. In addition, the intra- and intergroup formal discussion provides the opportunity to reflect, give feedback, and enable peer-teaching. Self-reflection enables learners to make a judgement when modifying their existing knowledge. Peer-to-peer teaching in TBL enhances learning and aids weaker learners to understand the course material (Park et al., 2014).

Some limitations of our study were that the sample size was small, reporting participants’ self-perception on how they felt after attending the workshop and the lack of longitudinal follow-up on retention of knowledge. In addition, we did not have a separate didactic lecture on the new classification as a control group to truly compare the two different modes of teaching. Future recommendation includes having two groups of GDPs to collate their perceptions as well as include a pre and post assessment to investigate the difference in improvement and in knowledge retention comparing TBL workshop and traditional didactic lecture, and include peer evaluation in TBL to increase accountability among learners. Besides, ethnographic research method can be explored to provide insight to researchers to understand the essence of how dental professionals learn during TBL. It would be meaningful to follow up this group of GDPs to assess the accuracy of their periodontal diagnoses based on the new classification to investigate the effectiveness of the TBL workshop. Of note, TBL workshops can be adapted into an online format; this is particularly useful during the current COVID-19 pandemic to engage learners and promote active learning in an online setting.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, TBL pedagogy may be another mode of teaching for GDPs in continuing dental education where participants are actively engaged, and direct application of knowledge gained can be made. During this pandemic, where face-to-face sessions are minimised, educators can consider adopting TBL pedagogy on an online platform to improve learning experience and engagement of their learners.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Lean Heong Foo is a Consultant Periodontist in Department of Restorative Dentistry and Head to the Dental Surgery Assistant Certification Programme in National Dental Centre Singapore. FLH reviewed the literature, contributed to study conception, data acquisition, data analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Dr Marianne M. A. Ong is a Senior Consultant Periodontist & Director of Education in National Dental Centre Singapore. MO contributed to study conception, data acquisition and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

This study was exempted from formal Centralised Institutional Review Broad review by SingHealth Institutional Review Board (CIRB Ref: 2021/2133).

Data Availability

Data is deposited at Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14411858

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Ms Safiyya Mohamed Ali for providing editorial support.

Funding

There was no funding involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Haj-Ali, R., & Al Quran, F. (2013). Team-based learning in a preclinical removable denture prosthesis module in a United Arab Emirates dental school. Journal of Dental Education, 77(3), 351–357.

Hrynchak, P., & Batty, H. (2012). The educational theory basis of team-based learning. Medical Teacher, 34(10), 796–801.https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.687120

Michaelsen, L. K., Parmelee, D. X., McMahon, K. K., & Levine, R. E. (2008). Team-based learning for health professions education: A guide to using small groups to improving learning. Stylus.

Park, S. E., Kim, J., & Anderson, N. K. (2014). Evaluating a team-based learning method for detecting dental caries in dental students. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 3(2), 100-105. https://doi.org/10.5430/jct.v3n2p100

Tonetti, M. S., Greenwell, H., & Kornman, K. S. (2018). Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. Journal of Periodontology, 89(Suppl 1), S159–S172. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0006

*Foo Lean Heong

National Dental Centre Singapore,

5, Second Hospital Avenue,

168938 Singapore

Email: foo.lean.heong@singhealth.com

Submitted: 29 March 2021

Accepted: 28 September 2021

Published online: 4 January, TAPS 2022, 7(1), 102-105

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-1/SC2508

Mairi Scott & Susie Schofield

Centre for Medical Education (CME), School of Medicine, University of Dundee, Scotland, United Kingdom

Abstract

Introduction: The switch to online off-campus teaching for universities worldwide due to COVID-19 will transform into more sustainable and predictable delivery models where virtual and local student contact will continue to be combined. Institutions must do more to replace the full student experience and benefits of learners and educators being together.

Methods: Our centre has been delivering distance blended and online learning for more than 40 years and has over 4000 alumni across five continents. Our students and alumni come from varied healthcare disciplines and are at different stages of their career as educators and practitioners. Whilst studying on the programme students work together flexibly in randomly arranged peer groups designed to allow the establishment of Communities of Practice (CoP) through the use of online Discussion Boards.

Results: We found Discussion Boards encouraged reflection on learning, sharing of ideas with peers and tutors, reduce anxiety, support progression, and enable benchmarking. This led to a highly effective student sense of belonging to each other, our educators, and the wider University, with many highlighting an excellent student experience and maintaining a thriving CoP within the alumni body.

Conclusion: Despite being based on one large postgraduate programme in medical education, our CoP approach is relevant to any undergraduate programme, particularly those that lead to professional qualification. With our mix of nationalities, we can ‘model the way’ for enabling strong CoP’s to share ideas about best practice with a strong student and alumni network which can be shared across the international healthcare community.

Keywords: Communities of Practice, Sense of Belonging, Student Experience

I. INTRODUCTION

The sudden switch to online, dual delivery and on-campus/off-campus teaching for Universities worldwide will not be reversed at the end of the current COVID-19 crisis but will transform into a more sustainable and predictable delivery model where virtual and local student contact will continue to be combined. The switch, known as Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) (Hodges et al., 2020) achieved much in a short timeframe but institutions need to do more to truly replace the full student experience and benefits of learners and educators being together on-site. The need for this new approach is acute in professional-based courses such as medicine where students need to learn complex skills within the context of healthcare delivery. These skills are acquired through multiple interactions with clinical colleagues in the workplace which, although often brief, are focused in real-time.

Given that the learning environment is dependent on the institutional ‘personality, spirit, and culture’ (Holt & Roff, 2004, pp. 553), human interaction is necessary to create that culture. We must develop new approaches to delivering medical education by merging established educational technologies with virtual approaches to establish on-line interaction with peers and senior colleagues such as can be achieved in Communities of Practice (CoPs) (Lave & Wenger, 1991). CoPs are social structures where people can share ideas, stories, and experiences relevant to the community’s activities. They help participants make sense of new knowledge and enable novices to benefit from working with experts, thus reducing anxiety, supporting progression, and enabling benchmarking. These components lead to the creation of a rich environment for information-sharing which has become increasingly important within healthcare delivery organisations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We have built on over 40 years’ experience of delivering distance, blended and online Masters-level accredited medical education learning across five continents to ‘model the way’ to providing a strong student experience for online learners. Our students and alumni come from various interdisciplinary healthcare disciplines, at different stages of their career as educators and practitioners.

II. METHODS

Several Discussion Boards (DBs), usually one per study week plus one for assignment questions are created in each 12-week Moodle-based module. Students are randomly assigned to groups to work together flexibly within these peer groups. Each discussion has a ‘prompt’ linked to that week’s work, designed to create CoPs and a highly effective student sense of belonging (SoB) to each other and programme educators. In the first module students are actively encouraged to participate, with emphasis being on the ‘safe space’ created that allows them to learn effectively from and with each other. DB comments are used as part of programme enhancement and quality assurance. Students give informed consent to their evaluation comments within DBs being extracted for overall programme review.

III. RESULTS

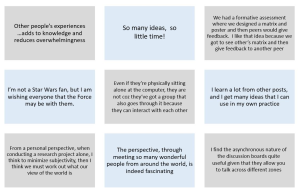

As students move from legitimate peripheral participant to experienced member, they often express increased confidence that their posts will allow them to share their view and help colleagues. The forum posts have been analysed as part of a much larger study; the following diagram (Figure 1) highlights some of the benefits.

Figure 1. Sample of comments in DBs posts

Our experience over the last four years is that student levels of interaction increase the further into the programme they go, suggesting that they value and enjoy it. Overall, when asked specifically if that assumption is correct, feedback from students is exceptionally positive and they comment on their achievement of a SoB through engagement with the DBs. Many highlight the excellent student experience. Another indirect indication of success is that student module success rate averages 93% across the modules, which is high for an online learning programme.

The benefits of using DBs are threefold:

- They allow for reflection on learning in real-time due to regular module-specific weekly activities requiring students to reflect on that week’s educational materials and post their thoughts on the DBs.

- They allow sharing with peers and tutors, establishing CoPs: The DB posts create peer-to-peer dialogue, encouraging students to practise the language of the discipline in a safe, supported environment. Learning activities are based on the principle of linking previous experience with the interpretation of new knowledge, thus enabling an escalation of the complexity of questions to enhance deeper connection and dialogue. Although essentially (and importantly) it is the students as peers who are encouraged to respond to each other’s questions and comments, the tutors do monitor posts, providing input when necessary and desirable. In some modules, students are required to give peer feedback on draft assignments using a 1:4 ratio to encourage a range of views and expertise, increasing the depth and extent of their critical thinking and analysis. This also gives them practice in giving and receiving feedback, an essential skill for future medical educators.

- CoPs build trust in colleagues and a SoB within the learning environment, leading to an excellent learning experience. Students state that they value the tutor contribution as this increases the confidence they have in their own online comments, sometimes shifting the discussion to a more profitable area for new learning in a way that was not pre-planned or even at times expected.

IV. DISCUSSION

Our approach to the creation of CoPs is based on the principle that in order to establish student trust and a SoB DBs are an essential tool. Management research describes trust within organisations as being multifaceted, with the main components being capability, well-meaning intent, and integrity (Ridings et al., 2002). It is accepted that within our programmes both tutor and student capabilities have been established. Integrity is established by clearly explaining the expected mode of student behaviour at the outset and demonstrated as students work through the programme. Well-meaning intent is demonstrated by acts of positive reciprocation built up over time by asking students to give peer feedback frequently and around increasingly complex activities. Both integrity and well-meaning intent therefore need to have a continued focus during module design and delivery and throughout the assessment process.

Now that medical education has been forced to re-evaluate the place of online learning as a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis, it seems inevitable that many of the discovered benefits will lead to significant changes in the way we teach and learn. Davis (2018) explored a future medical school being one ‘without walls’ by which he meant that the artificial separation of the ‘classroom and the clinic’ would inevitably diminish as we embraced flipped classrooms and online collaborative learning.

If we adopt this approach for student learning it may also change the way we think about faculty development, as we could create extensive networks of faculty development special interest grouped CoPs beyond the ‘walls’ of our own schools. A recent study by Chan et al. (2018) in McMaster describes the creation of a Faculty Incubator – a virtual CoP which uses a longitudinal, asynchronous, online platform to deliver a one-year curriculum to support early-to mid-career educators from 30 different locations with their professional development. This widespread (geographically) collaborative approach was found to be well received, with lively interactions which broke down some of the boundaries that normally prevent early career academics from approaching unknown colleagues in different locations, colleagues they would normally never have met in person.

An additional challenge created by the COVID-19 pandemic was the necessity for healthcare professionals to make clinical decisions in an ‘evidence-poor’ disease by gathering emerging data (often by word-of-mouth) and treating patients without the certainty of a knowledge base built up over decades of robust randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence. This is described by Rosenquist (2021, pp. 8) as a kind of “Bayesian fatigue”: a stress-induced dysphoria experienced when the corpus of knowledge that is the foundation of one’s work acquired over decades, becomes less important than information being gathered from disparate sources in real time.’ The ‘disparate sources’ referred to here are groups of widely dispersed practitioners (within current and new CoPs) who are sharing individual and collective rapid learning by experience that has become necessary when treating patients with COVID-19. These CoPs are based on the collective trust healthcare professionals express in valuing the views of colleagues struggling with similar challenges. This helps reduce that ‘Bayesian’ impact when it comes to making difficult clinical decisions in real time with limited evidence. However, trust within a CoP also comes from previous positive experience of being within other CoPs, and so it is important that we as medical educators enable our students to have experience of the value of sustainable CoPs in their own learning. Despite the limitations of the range of the study comments, we believe that given the extent of the sudden switch to ERT our findings of use of DBs to establish much appreciated CoPs justifies early dissemination through this short communication.

V. CONCLUSION

As medical educators we must have the skills necessary to establish strong and sustainable CoPs to educate current and future healthcare professionals in this effective way of learning from each other. This can be done as effectively with online learning as with on-campus interaction, allowing the possibility of the widespread creation of truly effective international CoPs sustainable for years to come.

Notes on Contributors

Professor Mairi Scott reviewed the literature, selected the data, wrote the manuscript, created the presentation and presented the materials virtually to the Conference. Dr Susie Schofield reviewed the literature, advised on the selection of the data and gave critical feedback on the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approved was granted by School of Medicine & School of Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 4HN on 03/05/19. Application Number: 19/41.

Data Availability

Ethical approval specified that raw data would not be made available for others out with the Centre ‘beyond the anonymised published or reported versions within the dissemination strategy’.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr Thillainathan Sathaananthan (PhD student) and Dr Linda Jones (PhD supervisor, Senior Lecturer) CME, University of Dundee, who produced some of the outcomes as part of research into student experiences with online learning and the use of Discussion Boards.

Funding

No grant or external funding was received for this work.

Declaration of Interest

Both authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Chan, T. M., Gottlieb, M., Sherbino, J., Cooney, R., Boysen-Osborn, M., Swaminathan, A., Ankel, F., & Yarris, L. M. (2018). The ALiEM faculty incubator: A novel online approach to faculty development in education scholarship. Academic Medicine, 93(10), 1497–1502. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002309

Davis, D. (2018). The medical school without walls: Reflections on the future of medical education. Medical Teacher, 40(10), 1004–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1507263

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/%20articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Holt, M. C., & Roff, S. (2004). Development and validation of the Anaesthetic Theatre Educational Environment Measure (ATEEM). Medical Teacher, 26(6), 553-558. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001711599

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Ridings, C. M., Gefen, D., & Arinze, B. (2002). Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities: The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(3-4), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0963-8687(02)00021-5

Rosenquist, J. N. (2021). The stress of Bayesian medicine—Uncomfortable uncertainty in the face of COVID-19. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(1), 7-9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018857

*Mairi Scott

Centre for Medical Education,

University of Dundee

Email: m.z.scott@dundee.ac.uk

Submitted: 15 January 2021

Accepted: 12 April 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 142-145

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/SC2489

Anne Thushara Matthias1, Gam Aacharige Navoda Dharani1, Gayasha Kavindi Somathilake2 & Saman B Gunatilake1

1Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Gangodawila, Sri Lanka; 2 National Centre for Primary Care and Allergy Research, University of Sri Jayewardenepura, Sri Lanka

Abstract

Introduction: Multiple factors influence doctor-patient communication. A good consultation starts with an introduction of him or herself by the doctor to the patient. The next step is to address patients in a manner they prefer. There is a paucity of data about how best to address patients in an Asian country. This study investigates how patients prefer to be addressed by doctors.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study conducted from July 1st to August 31st, 2020 at a single Centre: Colombo South Teaching Hospital in Sri Lanka.

Results: Of 1200 patients, 63.25% reported that doctors never introduced themselves and 97.91% of patients reported, doctors never inquired how to address them. 49.9% preferred to be addressed informally (as mother, father, sister) than by the name (first name, last name, title). The older female patients, married patients, patients of lower education, and lower monthly income preferred to be addressed informally.

Conclusion: Most doctors did not introduce themselves to patients during medical consultations and did not inquire how patients wish to be addressed.

Keywords: Doctor-Patient Relationship, Medical Consultation, Professionalism, Introduction, Doctor’s Name Badge, South Asian, Sri Lanka

I. INTRODUCTION

Professionalism plays an important role in the practice of medicine. The Charter on Medical Professionalism has a set of 10 commitments. Commitment to professional responsibilities is one of them. It includes the way doctors dress and conduct themselves during a consultation (Blank et al., 2003). Abiding by these principles, doctors can improve their interaction with patients resulting in a better outcome (Gillen et al., 2018) A good introduction will facilitate a positive attitude from the patient towards the doctor. “#hellomynameis” campaign in the UK was initiated to create awareness about the importance of an introduction (Egener et al., 2017).

Professionalism is impacted by social, cultural, and economic factors. It is believed that the translation of professionalism concepts across the world should consider national cultural difference. Studies from western populations have shown that most patients prefer being addressed by their first name and for the doctor to be introduced by their full name and title (Egener et al., 2017). There is a paucity of data on how Asian patients wish to be addressed.

The Sri Lankan society is hierarchical based on age, caste, wealth, educational qualifications, and profession. Respect for doctors comes naturally in this system. Doctors are treated with great respect in rural communities. It is quite common to find doctors not introducing themselves to the patient and expecting them to know who you are. In Sri Lanka, doctors tend to address the patients mostly informally addressing the patient as a family member- ‘father, mother, uncle, sister, etc.’, in the local language assuming it would connect with the patient better. This study explores the way doctors address patients in an Asian cultural setting and the patient’s expectations.

II. METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted from 1st July to 31st August 2020 at the Colombo South Teaching Hospital. A total of 1200 patients were selected from the wards in a sequential, systematic manner with a skip interval of one. Informed verbal consent was obtained from the participants. The first part of the questionnaire contained demographics. Some questions asked the participants about how they wish to be addressed and how doctors addressed them and how they would like their doctor to introduce themselves. Informal methods of address were mother, father, sister, etc. Formal methods were the use of the first name, last name, or titles.

Statistical analysis including the statistical significance tests was performed using SPSS IBM SPSS Statistics Version 20 IBM Corp. (2017), IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. Pearson Chi-Square Association Test was used to identify the statistically significant associations between the categorical variables at a confidence level of 95%.

III. RESULTS

A. Demographics

(See Table 1)

Of the 1200 participants, 868 (72.33%) were female. Of the sample, 1022 (85.16%) were from urban areas.

|

Characteristics |

Number of participants (%) |

||||

|

Informal method

|

First name

|

Last name

|

No preference

|

||

|

Total |

|

599 |

427 |

77 |

79 |

|

Age |

Below 40 (< 40) (664) |

253 (38.10%) |

312 (46.99%) |

33 (4.97%) |

49 (7.38%) |

|

Above 40 (> = 40) (536) |

346 (64.55%) |

115 (21.46%) |

44 (8.21%) |

30 (5.60%) |

|

|

Education Level |

Post Graduate & Graduate (147) |

54 (36.73%) |

56 (38.1%) |

10 (6.8%) |

9 (6.12%) |

|

|

Grade 6-A/L (986) |

501 (50.81%) |

359 (36.41%) |

60 (6.09%) |

66 (6.69%) |

|

|

Grade 1-5 & Not educated (67) |

44 (65.67%) |

12 (17.91%) |

7 (10.44%) |

4 (5.97%) |

|

Income |

>100,000 (61) |

15 (24.6%) |

23 (37.7%) |

4 (6.56%) |

6 (9.84%) |

|

|

20,000-100,000 (982) |

490 (49.9%) |

357 (36.35%) |

66 (6.72%) |

64 (6.52%) |

|

|

<20000 (157) |

94 (59.87%) |

47 (29.93%) |

7 (4.45%) |

9 (0.75%) |

|

Occupation |

Skilled Occupations (581) |

251 (43.2%) |

230 (39.59%) |

40 (6.88%) |

84 (14.46%) |

|

|

Unskilled occupations (591) |

339 (57.36%) |

178 (30.11%) |

37 (6.26%) |

37 (6.36%) |

|

|

A/L & Uni students (28) |

9 (32.14%) |

19 (67.86%) |

– |

– |

Table 1. Difference between how patients wish to be addressed and vice versa

B. How Doctors Addressed Patients

Of the 1200 patients, 1175 (97.91%) reported that doctors never inquired how to address them at the beginning of the consultation (Matthias, 2021). A large proportion, 1124 (93.66%) reported that doctors have addressed them informally and 599 (49.9%) preferred being addressed informally, 427 (35.58%) preferred to be addressed by their first name, and 77 (6.41%) by their last name. Only 18, preferred to be addressed by their title (Dr/Rev).

More females preferred to be addressed informally when compared to the males (451/868 (51.96%) vs 148/332 (44.58%) (Pearson Chi-Square = 4.345, p = 0.037). Married patients preferred to be addressed informally when compared to the unmarried/divorced/separated (578/1089 (53.1%) vs 21/111 (18.9%), Pearson Chi-Square = 54.339, p < 0.001). The ethnicity of the patients and the area they are from (Urban/Rural) had no significant impact on how they desired to be addressed.

Over 65% of the patients (44/67) with a lower level of education preferred being addressed in an informal way whereas only 36.7% (54/147) of the graduates/post graduates preferred the informal way (Pearson Chi-Square = 23.264, p < 0.001). Monthly family income was a statistically significant variable and patients with a higher family income (Over LKR 100,000) preferred to be addressed more formally when compared to patients with an income below LKR 20,000 (40/61 = 65.57% Vs 54/157 = 34.39%, Pearson Chi-Square = 23.928, p < 0.001). The occupations of the patients are also a significant factor which affected their preference in the way being addressed with 57.4% of the patients with unskilled occupations (UN) and 43.2% of the ones with skilled occupations preferring the informal way (339/591 = 57.36% vs 251/581 = 43.20%, Pearson Chi-Square = 34.771, p < 0.001). Older patients (40 and above) preferred to be addressed informally when compared to others. (346/536 = 64.6% Vs 253/664 = 38.1%, p < 0.001).

Of 1059 patients, 495 (46.7%) preferred being addressed the informal way as they felt it made the doctor-patient relationship more personal and 627 (59.2%) patients felt the doctor treated them as their relative. Of the Doctors, 759 (63.25%) did not introduce themselves to the patients and 865 patients (72.08%) prefer doctors to wear a name badge. 718(59.8%) wanted doctors to introduce themselves with the title, doctor’s designation and specialty. 246(20.5%) wanted doctors to tell their title and first name. Only 4(0.3%) didn’t want doctors to introduce themselves.

IV. DISCUSSION

One important finding from our study was that doctors did not introduce themselves to patients. In most state sector hospitals in Sri Lanka, doctors do not wear a white coat or a name badge at present. A study done in the UK showed that 59.1% of patients and in our study 72% felt that doctors should wear name badges as a form of identification (Van Der Merwe et al., 2016). In our study, 98% of patients reported that doctors never inquired how to address them at the beginning of the consultation. To improve this aspect, these areas should be included in the objectives of the medical curriculum and continuous medical education programs of young doctors. The “Personal and professional development stream” which is taught in the medical faculty at Sri Jayewardenepura in Sri Lanka is an avenue that can be used for this purpose.

Social, cultural, ethnic, and other demographic factors can influence preferred modes of address. In our study, 50% prefer to be addressed in the informal way. There are several possible reasons for this. Sri Lankan people have long-standing cultural and religious beliefs. Sri Lankan traditions revolve around two dominant religions Buddhism & Hinduism. Filial piety, respect for one’s parents and elders, is a concept that is present in Asian countries. Addressing a person as a mother, father, son, etc. is considered as showing respect. The patients feel the doctors treat them as their own family or relative when they are addressed this way.

In studies done in most western countries, patients wish to be addressed by their first name. The higher the income and higher the education level of the patient, the lower is their preference for being addressed the informal way as they might perceive it as less professional. To solve the dilemma of whether to call the patient formally or informally and to make sure the patient is addressed according to their preference, the best approach would be to question the patient about their preferred name during their initial consultation and to record that in the patient’s records.

A. Strengths and Limitations

The large number of participants and recruiting from different wards; medical, surgical, paediatric, gynecology, and obstetrics to cover patients who were in the hospital for different illnesses are strengths. Not only did the study examine the patients’ preferred method of address, it examined the reasons behind the preference.

V. CONCLUSION

Our findings support a patient preference for informal greetings from their doctors in half the study population. It is not safe to assume that the patient can be addressed anyway the doctor deems right and it is good practice to ask patients how they prefer to be called at the beginning of the consultation. Doctors should introduce themselves clearly to patients and the current rates of introduction are inadequate. Majority of the patients prefer doctors to wear a name badge. In order to address patients in a culturally appropriate and patient preferred method it is always useful to ask the patient how they wish to be addressed.

Notes on Contributors

Anne Thushara Matthias was involved in conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Gam Aacharige Navoda Dharani was involved in investigation and data Curation, Gayasha Kavindi Somathilake was involved in formal analysis and Saman B Gunatilake was involved in writing final draft and review.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was from the Ethics Review Committee of the Colombo South Teaching Hospital(ERC 873/2020). There were no ethical issues. Informed consent was taken from the participants.

Data Availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request https://figshare.com/s/e6db9a7246f9ef08474a10.6084/m9.figshare.13633949 (Matthias, 2021).

Funding

No funding sources are associated with this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Blank, L., Kimball, H., McDonald, W., & Merino, J. (2003). Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter 15 months later. Annals of Internal Medicine, 138(10), 839–841. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00012

Egener, B. E., Mason, D. J., McDonald, W. J., Okun, S., Gaines, M. E., Fleming, D. A., Rosof, B. M., Gullen, D., & Andresen, M. L. (2017). The charter on professionalism for health care organizations. Academic Medicine, 92(8), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001561

Gillen, P., Sharifuddin, S. F., O’Sullivan, M., Gordon, A., & Doherty, E. M. (2018). How good are doctors at introducing themselves? #hellomynameis. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 94(1110), 204–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135402

Matthias, T. (2021). Patient preferences of how they wish to be addressed in a medical consultation – Study from Sri Lanka. https://figshare.com/s/e6db9a7246f9ef08474a

Van Der Merwe, J. W., Rugunanan, M., Ras, J., Röscher, E. M., Henderson, B. D., & Joubert, G. (2016). Patient preferences regarding the dress code, conduct and resources used by doctors during consultations in the public healthcare sector in Bloemfontein, free state. South African Family Practice, 58(3), 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2016.1187865

*Anne Thushara Matthias

Faculty of Medical Sciences,

University of Sri Jayewardenepura

Email: thushara.matthias@sjp.ac.lk

Submitted: 21 January 2021

Accepted: 16 April 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 135-141

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/SC2484

Caroline Choo Phaik Ong1,2, Candy Suet Cheng Choo1, Nigel Choon Kiat Tan2,3 & Lin Yin Ong1,2

1Department of Paediatric Surgery, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, SingHealth, Singapore; 2SingHealth Duke-NUS Academic Medical Centre, Singapore; 3Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute, SingHealth, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated use of technology like videoconferencing (VC) in healthcare settings to maintain clinical teaching and continuous professional development (CPD) activities. Sociomaterial theory highlights the relationship of humans with sociomaterial forces, including technology. We used sociomaterial framing to review effect on CPD learning outcomes of morbidity and mortality meetings (M&M) when changed from face-to-face (FTF) to VC.

Methods: All surgical department staff were invited to participate in a survey about their experience of VC M&M compared to FTF M&M. Survey questions focused on technological impact of the learning environment and CPD outcomes. Respondents used 5-point Likert scale and free text for qualitative responses. De-identified data was analysed using Chi-squared comparative analysis with p<0.05 significance, and qualitative responses categorised.

Results: Of 42 invited, 30 (71.4%) responded. There was no significant difference in self-reported perception of CPD learning outcomes between FTF and VC M&M. Participants reported that VC offered more convenient meeting access, improved ease of presentation and viewing but reduced engagement. VC technology allowed alternative communication channels that improved understanding and increased junior participation. Participants requested more technological support, better connectivity and guidance on VC etiquette.

Conclusion: VC technology had predictable effects of improved access, learning curve problems and reduced interpersonal connection. Sociomaterial perspective revealed additional unexpected VC behaviours of chat box use that augmented CPD learning. Recognising the sociocultural and emotional impact of technology improves planning and learner support when converting FTF to VC M&M.

Keywords: Teleconferencing, Morbidity and Mortality Meeting, Continuous Professional Development, Sociomaterial Theory

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic instigated worldwide social distancing and rapid uptake of technology to replace face to face (FTF) communication. Healthcare professionals at clinical workplaces adopted educational technological tools to maintain teaching for students, trainees and continuous professional development (CPD) activities (Cleland et al., 2020). Likewise, our hospital-based department pivoted from FTF to interactive web-based videoconferencing (VC) (Zoom) to continue patient-care quality audits and CPD learning.

Before the pandemic, there was limited interest in teleconferencing for health professions education apart from remote learning and formal CPD webinars (Chipps et al., 2012). VC for informal CPD like the Morbidity and Mortality meeting (M&M) was mentioned only to boost attendance of faculty based at distant campuses. The M&M is a regular audit practice of surgical departments that constitutes an important type of informal CPD for individual and organisational learning (de Feijter et al., 2013). Many guidelines exist for FTF M&M but there are none for VC M&M.

Sociomaterial theory examines the mutual relationship of humans with sociomaterial forces and the resultant changes i.e., humans acting on and influenced by objects, nature, culture and/or technology. It provides a useful perspective to evaluate the effect of VC CPD learning and practice by highlighting the importance of materiality – in this case, technology – that is overlooked by other human-centric sociocultural educational theories (Fenwick, 2014). Using sociomaterial framing, we aimed to review the impact of changing from FTF to VC M&M in terms of CPD learning outcomes and user experience.

II. METHODS

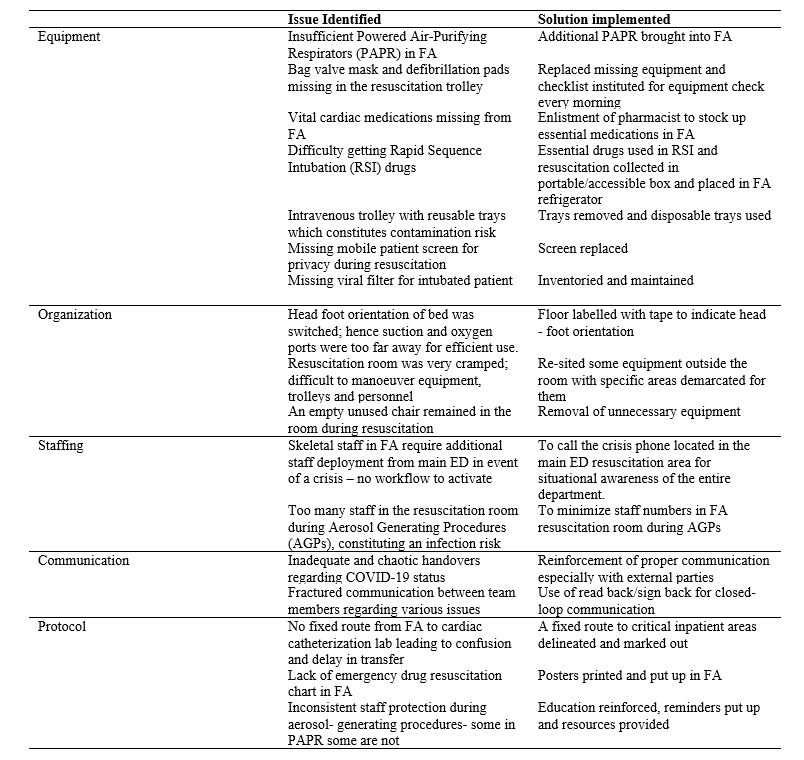

A. Description of Context

On 7 Feb 2020, Singapore declared Orange Alert (severity level 3 out of 4) on the national Disease Outbreak Response System in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nationwide infection control measures required staff social distancing in public hospitals. Our department (Appendix A: department context and demographics) organises weekly Journal club and M&M as regular CPD; these were converted from FTF to VC meetings from 25 March 2020 till present. Singapore has widespread digital literacy and familiarity with computer usage; our hospital has used electronic health records since 2018. These factors facilitated our rapid pivot to VC meetings.

B. Description of Study

With institutional research board ethics waiver (CIRB Ref: 2020/2697), we sent an email inviting all department staff to participate in a survey about their experience of VC M&M compared to FTF M&M. The sampling frame comprised 18 permanent staff and 24 temporary staff on rotation in the department, from 1 April to 30 June 2020.

The primary outcomes of the survey were self-reported perceptions comparing FTF and VC M&M, addressing categories of CPD learning relevant to M&M: knowledge, practice change, attitude, user outcomes and intention to change (Table 1: Q1-Q3). We asked additional questions (Q4-14) about the FTF/ VC learning environments to elicit possible technological effects on primary outcomes. Face validity of the questionnaire was assessed by authors CCPOng, NCKTan and LYOng who are physicians familiar with M&M.

Recruitment, data collection, data entry and de-identification was performed by author CSChoo (clinical research coordinator) who is outside the department clinical hierarchy. Survey non-responders were given two reminders by CSChoo before the final 3-week deadline. Consent was implied if participants returned the completed survey. Authors CCPOng and CSChoo analysed the de-identified data. Participants responded whether they agreed with the statement, using a 5-point Likert scale. We carried out Chi-squared comparative analysis on 3 grouped categories: (strongly agree+ agree); (neutral) and (disagree+ strongly disagree).

III. RESULTS

A. Descriptive Demographics

We received responses from 30 people out of 42 invited (71.4%) with similar response rates for permanent staff 13/18 (72.2%) and temporary staff 17/24 (70.8%). Appendix A provides details on age, gender, job grade of respondents and prior familiarity with VC.

B. Survey Findings

The participants had attended on average 18.7 (SD 13.4) FTF M&M and 15.1(SD 8.3) VC M&M in the preceding 12 months. Apart from VC M&M, all had attended some other VC event such as administrative meetings, tutorials, webinars and non-work-related workshops or dinners.

|

Q |

Perception |

Analysis* group |

FTF M&M |

VC M&M |

p-value |

|||||||||

|

Strongly disagree & Disagree |

Neutral |

Strongly Agree & Agree |

Strongly disagree & Disagree |

Neutral |

Strongly Agree & Agree |

|||||||||

|

Q1 |

I learnt new medical knowledge |

whole |

0 |

5(16.7) |

25 (83.3) |

1 (3.3) |

0 |

29 (96.7) |

0.043 |

|||||

|

sub |

0 |

1 (4.2) |

23 (95.8) |

1 (4.2) |

0 |

23 (95.8) |

0.368 |

|||||||

|

Q2 |

I learnt new skills (e.g. clinical, teaching, communication, research, team, practical) |

whole |

0 |

7 (23.3) |

23 (76.7) |

1 (3.3) |

5 (16.7) |

24 (80.0) |

0.508 |

|||||

|

sub |

0 |

3 (12.5) |

21 (87.5) |

1 (4.2) |

3 (12.5) |

20 (83.3) |

0.599 |

|||||||

|

Q3 |

I would change my practice based on what I learnt |

whole** |

0 |

7 (24.1) |

22 (75.9) |

1 (3.3) |

3 (10.0) |

26 (86.7) |

0.233 |

|||||

|

sub** |

0 |

3 (13) |

20 (87.0) |

1 (4.2) |

2 (8.3) |

21(87.5) |

0.548 |

|||||||

|

Q4 |

Junior staff are comfortable presenting |

whole |

2 (6.7) |

8 (26.7) |

20 (66.7) |

1 (3.3) |

3 (10.0) |

26 (86.7) |

0.184 |

|||||

|

sub |

2 (8.3) |

3 (12.5) |

19 (79.2) |

1 (4.2) |

2 (8.3) |

21 (87.5) |

0.729 |

|||||||

|

Q5 |

Participants are comfortable to ask questions to clarify |

whole |

4 (13.3) |

9 (30.0) |

17 (56.7) |

3 (10.0) |

7 (23.3) |

20 (66.7) |

0.728 |

|||||

|

sub |

4 (17.7) |

5 (20.8) |

15 (62.5) |

3 (12.5) |

6 (25) |

15 (62.5) |

0.890 |

|||||||

|

Q6 |

Participants are comfortable to raise concerns or disagree with management |

whole |

3 (10.0) |

10 (33.3) |

17 (56.7) |

4 (13.3) |

5(16.7) |

21 (70.0) |

0.328 |

|||||

|

sub |

3 (12.5) |

6 (25.0) |

15 (62.5) |

4 (16.7) |

4 (16.7) |

16 (66.7) |

0.750 |

|||||||

|

Q7 |

Tone of discussion is respectful |

whole |

4 (13.3) |

10 (33.3) |

16 (53.3) |

1 (3.3) |

6 (20.0) |

23 (76.7) |

0.132 |

|||||

|

sub |

3 (12.5) |

6 (25.0) |

15 (62.5) |

1 (4.2) |

5 (20.8) |

18 (75.0) |

0.506 |

|||||||

|

Q8 |

Participants are engaged during the meeting |

whole |

2 (6.7) |

9 (30.0) |

19 (63.3) |

6 (20.0) |

8 (26.7) |

16 (53.3) |

0.314 |

|||||

|

sub |

2 (8.3) |

4 (16.7) |

18 (75.0) |

6 (25.0) |

7 (29.2) |

11(45.8) |

0.105 |

|||||||

|

Q9 |

I can see the slides clearly |

whole |

0 |

9 (30.0) |

21 (70.0) |

2 (6.7) |

1 (3.3) |

27 (90.0) |

0.01 |

|||||

|

sub |

0 |

4 (16.7) |

20 (83.3) |

2 (8.3) |

1 (4.2) |

21 (87.5) |

0.148 |

|||||||

|

Q10 |

I can follow the discussion well |

whole |

0 |

5 (16.7) |

25 (83.3) |

3 (10.0) |

3 (10.0 |

24(80.0) |

0.172 |

|||||

|

sub |

0 |

1 (4.2) |

23 (95.8) |

3 (12.5) |

3 (12.5) |

18 (75.0) |

0.100 |

|||||||

|

Q11 |

It is easy to provide comments during the meeting |

whole |

3 (10.0) |

8 (26.7) |

19 (63.3) |

6 (20.0) |

6 (20.0) |

18 (60.0) |

0.519 |

|||||

|

sub |

3 (12.5) |

3 (12.5) |

18 (75.0) |

6 (25.0) |

6 (25.0) |

12 (50.0) |

0.202 |

|||||||

|

Questions about VC M&M only |

||||||||||||||

|

Q12 |

I find it easy to navigate the buttons/ commands |

Strongly disagree & Disagree |

Neutral |

Strongly Agree & Agree |

||||||||||

|

3 (10%) |

3 (10%) |

24 (80%) |

||||||||||||

|

Q13 |

I prefer to ask questions / comment by |

Typing |

No preference |

Audio |

||||||||||

|

15 (50%) |

12 (40%) |

3 (10%) |

||||||||||||

|

Q14 |

I prefer to have the video on/ off for |

Myself |

Host |

Presenter |

Participant |

|||||||||

|

On |

4 (13.3%) |

12 (40%) |

21 (70%) |

2 (6.7%) |

||||||||||

|

Off |

22 (73.3%) |

3 (10%) |

1 (3.3%) |

8 (26.7%) |

||||||||||

|

No preference |

4 (13.3%) |

15 (50%) |

8 (26.7%) |

20 (66.7%) |

||||||||||

Table 1. Results of the survey

Table 1 shows the collated responses to survey questions comparing experience of FTF and VC M&M (Q1-11) and questions specific to VC technology (Q12-14). There were six participants who either had zero experience of FTF M&M or had experienced FTF M&M only in other departments, not ours. We carried out subgroup analysis excluding these 6 persons to remove possible influence of other M&M styles, since the study focus was on impact of VC technology.

In general, self-reported perceptions of CPD outcomes were similar for both FTF and VC M&M. Participants appreciated that VC allowed us to continue M&M practice during the pandemic while acknowledging both positive and negative technological influences on process. Two questions (Q1 and Q9) had minor differences that were significant on whole group analysis but not significant on subgroup analysis. There was a trend towards decreased engagement for VC M&M compared to FTF M&M (Q8) that was not statistically significant.

When using VC (Table 1: Q12-14; Appendix B qualitative responses), more participants preferred to ask questions or comment by typing in the chat box than speaking on microphone. The most common reason given was to avoid interrupting meeting flow; some highlighted that the chat box facilitated junior staff participation. A few felt that keeping ‘video-on’ for all participants improved engagement but the rest preferred to have own ‘video-off’ with presenter ‘video-on’ to reduce distraction. Participants felt that while technology offered easier meeting access and simplified scheduling, it sometimes reduced engagement and interfered with community-building. Participants preferred more technological support, clearer guidance on expected VC behaviours, better infrastructure and connectivity.

A copy of the informed consent, survey questions and anonymised database are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13611611.v1.

IV. DISCUSSION

Sociomaterial perspectives offer new ways to conceptualise health professions education beyond individual cognitive and sociocultural educational lenses (Fenwick, 2014). Underpinned by diverse theories like cultural-historical activity theory, actor-network theory, and complexity theory, it recognises that “objects and humans act upon one another in ways that mutually transform their characteristics and activity” (Fenwick, 2014). Therefore, sociomaterial perspectives illuminate how technology (VC) and related infrastructure (devices and internet connectivity) interact with humans to modify the VC CPD learning environment.

In our context, widespread device penetration and free hospital Wi-Fi access aided rapid adoption of technology. Institution policy mandates internet separation from patient electronic health records, so staff use personal devices instead of hospital computers for meeting access, but it was otherwise straightforward to convert to VC M&M. Nevertheless, some unanticipated issues and VC behaviours manifested.

Introducing new technology is commonly associated with distress with learning how to use it. We chose Zoom as the most user-friendly VC platform because majority had no prior experience with VC. Unfortunately, early issues like ‘Zoom-bombing’ induced the company to make frequent user-interface changes that confused some users. A few participants (both younger and older) felt inadequately supported during their learning curve. We had provided a simple guidance document with link to online Zoom technical support but most preferred trial and error and asking for help during meetings.

Technical support alone is insufficient to address discomfort caused by social aspects of changed processes. We anticipated that uncertainty about protocols or inappropriate participant behaviours could lead to disengagement with poor CPD outcomes. We preempted these risks by following the same CPD framework as FTF M&M (e.g. moderator controls discussion, presentation template, focus on peer review learning without blame) and instituted additional VC safeguards for patient confidentiality by limiting patient identifiers, preventing recording and confirmation of attendee identity for meeting admission. We naturally evolved VC etiquette of queueing using the ‘raise-hand’ button while the moderator invites discussants by name and manages their order.

An ethnographic study of distributed VC in undergraduate medical education found that unintended ‘technologies of exposure’ – visual, curricular and auditory, discomforted the faculty and students (MacLeod et al., 2019). Similarly, many in our study disliked having their ‘video-on’. Although ‘video-on’ could improve interpersonal trust, visual exposure discomfort may interfere with aims of improved engagement and relationship-building. Originally, our department encouraged but did not mandate universal ‘video-on’. Gradually, it became the norm for all to have ‘video-off’ except the host and presenter. Despite ‘video-off’, we can maintain honest conversations necessary for M&M because of trust built through years of training and working together. Prolonged loss of FTF contact may erode trust, hence we created a departmental WhatsApp chat group to enhance social connection.

VC technology afforded unexpected learning contributions. The chat box promotes participation of reticent staff, both senior and junior, especially those preferring written expression; it augments understanding of audio discussion and allows sharing of links to supporting literature. The ease of participation empowers juniors and shifts focus from the vocal few who dominated FTF M&M. While the VC constraint of turn-taking for speakers slows down discussions, it improves interprofessional respect and meeting discipline when host can ‘mute’ the recalcitrant interrupter.

V. CONCLUSION

Sociomaterial perspectives highlight how VC technology changes the CPD learning environment of the M&M. VC provides improved access for participation and alternative communication channels but potentially reduces engagement. Recognising constraints and trade-offs of technology-driven enhancements allows better planning and learner support in VC CPD.

Note on Contributor

Caroline Choo Phaik Ong reviewed the literature, designed the study, analysed de-identified data and wrote the manuscript. Candy Suet Chong Choo performed data collection and de-identification, analysed the data and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript. Nigel Choon Kiat Tan reviewed the literature, advised the design of the study and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript. Lin Yin Ong advised design of the study and gave critical feedback to the writing of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approve the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study received institutional research board ethics waiver (CIRB Ref: 2020/2697).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the participants of the survey for sharing their responses freely.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

All the authors have no declarations of conflicts of interest.

Data availability

A copy of the informed consent, survey questions and anonymised database are available at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13611611.v1 under CC0 licence.

References

Chipps, J., Brysiewicz, P., & Mars, M. (2012). A systematic review of the effectiveness of videoconference-based tele-education for medical and nursing education. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 9(2), 78-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2012.00241.x

Cleland, J., Tan, E. C. P., Tham, K. Y., & Low-Beer, N. (2020). How COVID-19 opened up questions of sociomateriality in healthcare education. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 25(2), 479-482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09968-9

de Feijter, J. M., de Grave, W. S., Koopmans, R. P., & Scherpbier, A. J. J. A. (2013). Informal learning from error in hospitals: what do we learn, how do we learn and how can informal learning be enhanced? A narrative review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 18(4), 787-805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-012-9400-1

Fenwick, T. (2014). Sociomateriality in medical practice and learning: Attuning to what matters. Medical Education, 48(1), 44-52. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12295

MacLeod, A., Cameron, P., Kits, O., & Tummons, J. (2019). Technologies of exposure: Videoconferenced distributed medical education as a sociomaterial practice. Academic Medicine, 94(3), 412-418. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002536

*Caroline CP Ong

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital,

100 Bukit Timah Road,

Singapore 229899

Tel: +65 63941113

Fax: +65 62910161

Email: Caroline.ong.c.p@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 27 January 2021

Accepted: 1 April 2021

Published online: 5 October, TAPS 2021, 6(4), 131-134

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-4/SC2478

Lean Heong Foo & Marianne Meng Ann Ong

Department of Restorative Dentistry, National Dental Centre Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused the COVID-19 pandemic which started in 2020. This resulted in a disruption to educational activities across the globe. Dental education, in particular, was affected because of its vocational nature where learners come into close contact with patients when performing dental procedures.

Methods: This is a narrative review with no research data analysis involved.

Results: Social distancing measures introduced to curb the spread of the infection revolutionised the advancement of online education as the virtual environment is a safer place to conduct teaching compared to face-to-face teaching. In this article, we share our experience at the National Dental Centre Singapore (NDCS) in ensuring the safety of our faculty and learners when conducting didactic and clinical education during the pandemic. Didactic lectures were conducted in the virtual environment via synchronous and non-synchronous teaching. Essential clinical education was conducted in small groups with safe management measures in place. In addition, we provide guidelines to highlight the importance of meticulous planning, thorough preparation, and seamless delivery in conducting effective synchronous teaching.

Conclusion: Safe management measures put in place to ensure the well-being of our faculty and learners can ensure dental education continuity during the pandemic.

Keywords: Dental Education, Education Continuity, COVID-19

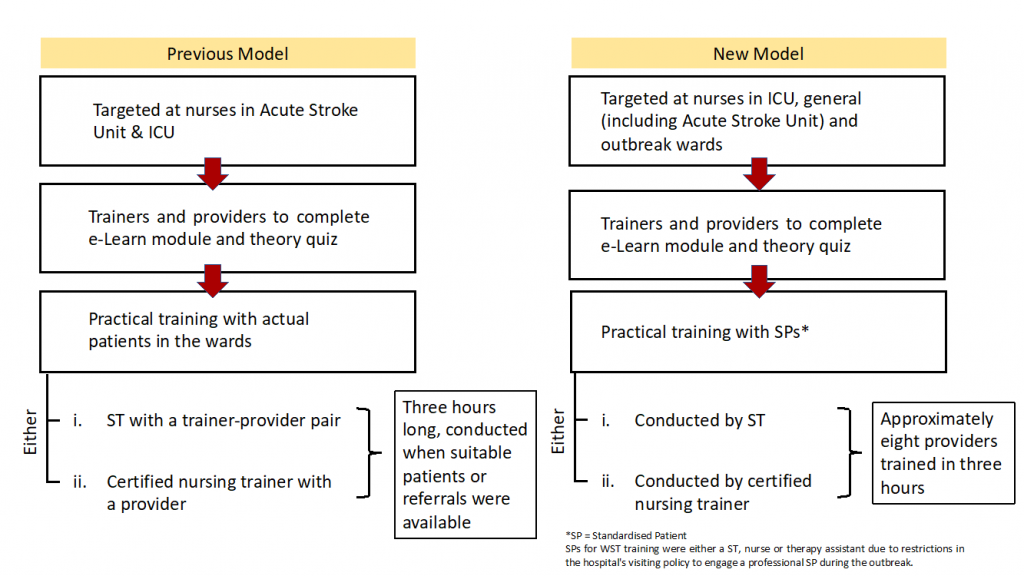

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic is severely affecting dental professionals since the Department of Labor Occupational and Health Administration United States of America (USA) published guidelines associating aerosol-generating procedures (AGP) in dentistry with SARS-CoV-2 virus spread. Many dental schools in the USA and Asia Pacific have desisted clinical practice and simulation sessions, causing severe disruption in dental training (Chang et al., 2021). Innovative guidelines were developed to conduct dental education during the pandemic (Hong et al., 2021). Singapore has undergone five phases during the pandemic: Pre-pandemic, Circuit Breaker (CB), Phase 1, Phase 2, and Phase 3 (current). We share our experience in continuing dental education for oral healthcare team learners (residents, dental technicians trainees, dental assistant trainees) in NDCS during the pandemic.

II. CLINICAL ADJUSTMENTS

After the Ministry of Health Singapore (MOH) raised the Diseases Outbreak Response System Condition (DORSCON) level from yellow to orange on 7th February 2020 (Pre-pandemic), NDCS senior management immediately adopted team segregation by establishing three self-contained teams comprising clinicians, dental surgery assistants, lab technicians, patient service associate executives, and health attendants (Tay et al., 2020). Learners at NDCS were also assigned to teams. All staff and learners were briefed on safe management measures to observe during clinical sessions. They were required to wear a surgical mask at all times except during meals, perform hand hygiene with an alcohol-based hand sanitiser, and report their temperature twice daily online. Triage and risk assessment of patients were carried out (Hong et al., 2021; Tay et al., 2020) and dental procedures were limited to emergency procedures to relieve pain, ongoing dental treatment, and dental clearance before medical procedures during CB. Use of personal protective equipment (PPE) comprising an eye shield, N95 mask or respirator, surgical gown, and gloves were indicated for all AGP while the use of an eye shield, surgical mask, and surgical gown was indicated for non-AGP following a risk-based assessment (Tay et al., 2020). Patients with suspected COVID-19 or who had close contact with a confirmed case were treated in a negative pressure room with proper PPE. All patients were required to rinse with cetylpyridinium chloride mouth rinse before their procedure. A 15-minute window in between patients was implemented to disinfect the operatory until Phase 3.

III. EDUCATION PROGRAMME ADJUSTMENTS

We conduct three structured education programmes in NDCS–National Institute of Technical Education (NITEC) Dental Assisting (DA), NITEC Dental Technology (DT), and National University of Singapore Master of Dental Surgery Residency Training Programme (RTP) for six dental specialties. In addition, Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) Diagnostic Radiography (DR) students have observation attachments at NDCS. During CB, Phase 1, and Phase 2, we postponed the new intake of learners for DA due to logistic issues with our collaborators. The posting of DR learners to our centre was also halted. All existing DA and DT learners were allocated to the same clinical team and completed their programme during the pandemic. Residents in the RTP were divided into two groups; one group was based in NDCS and the other in National University Centre for Oral Health Singapore during the 7-week CB. From Phase 1 onwards, the two groups of residents started weekly alternating rotations for their clinical sessions between the two institutions.

NDCS education activities are classified into didactics and clinical sessions. We conducted didactics using synchronous and non-synchronous formats while clinical sessions gradually resumed from Phase 1 to 3 following prevailing MOH and institutional policies. Synchronous teaching and seminars were carried out using Zoom and WebEx online platforms. Voice annotated presentations and e-learning modules were launched in the SingHealth e-learning platform, Wizlearn, for non-synchronous teaching. Clinical sessions were conducted with a small clinical supervisor-learner ratio (1:5), triage of patients, use of complete PPE with an N95 mask, hand hygiene, and high suction evacuator for AGP (Tay et al., 2020). Face-to-face sessions for essential hands-on clinical skills building were organised in Phase 2 and 3 with safe management measures in place such as small instructor-learner ratio, safe distances between learners and instructors, segregation of learners and instructors in groups, donning of surgical masks, meticulous hand hygiene, and proper disinfection after equipment use (Tay et al., 2020).

IV. GUIDELINES FOR ONLINE SYNCHRONOUS TEACHING

Mayer’s theory of multimedia learning (Mayer, 2002) describes the learning process in online education by highlighting the dual channels (auditory and visual) and three stages of memory (sensory, working, and long-term) for processing information. The learner’s eyes and ears capture diagrams and text in the multimedia presentation with sensory memory input. These are converted into a pictorial and verbal mode respectively in the working memory and integrated with prior knowledge from the long-term memory. Educators should prevent cognitive overload in content planning, as learners have limited capacity to hold the pictorial and verbal mode in working memory. A three-phase guide highlighting salient information for conducting effective online synchronous teaching is provided.

A. Meticulous Planning

To understand learners, faculty can adopt a 5W and 1 H concept [(who (the learners), where (location of teaching), why (learning objectives), what (lesson content), when (duration), and how (online platform in this context)] when planning a teaching module. Besides, faculty can construct the learning objectives and teaching activities using Bloom’s taxonomy based on learning outcomes. Bloom’s taxonomy covers six cognitive domains in the following order: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, where a higher-order is more complicated for the learners to master and demonstrate.

B. Thorough Preparation

Apart from teaching material, a faculty guide is recommended. It should contain the schedule and details of the teaching session, teaching activities, and probing questions and answers for reference; to ensure all the teaching tasks are completed within the planned schedule. Handouts are used to reduce cognitive overload and as a backup when the connection is down. Generally, a good camera, laptop or smartphone, internet connection, a simple background with light, and a quiet room are sufficient for online teaching.

C. Seamless Delivery

Good online synchronous teaching platforms include Zoom, WebEx, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Mikogo, and Slack with breakout rooms and annotation board features that are included in the premium subscription of these platforms. A dry run is recommended to familiarise oneself with the functions on the various platforms. Setting the learning climate during the session by preparing learners to respond at appropriate times is crucial. The faculty should look at the camera frequently to keep eye contact with learners. Backup plans that include standby internet access and soft copy handouts are useful when connection is down. Increased feedback and communication between faculty and learners is crucial in online teaching and can be achieved by:

i) Using a learning management system such as GoSoapBox to allow learners to input text individually, particularly useful for clinical case discussion.

ii) Using Slido or Poll Everywhere to conduct needs analysis or summative or formative assessment between teaching.

iii) Utilising the question and answer segment to assess learners’ responses and check progress.

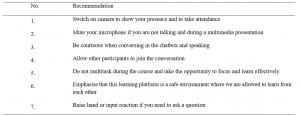

iv) Using the chatbox to allow learners to post questions and comments.

Teleconferencing has limited non-verbal cues coupled with milliseconds delay in observation by other participants that can subconsciously force our brain to restore the synchrony present in face-to-face contact. This overworking can lead to tiredness and discomfort from virtual teleconferencing tools, termed as ‘Zoom fatigue’. Recommendations to reduce Zoom fatigue include taking a rest in between brief lessons and turning off the camera when muted to reduce stimulus and mental fatigue. Netiquette, a blend of ‘internet etiquette’, refers to a code of good behaviour for both educators and learners (Table 1) that should be practised in an online environment (Lateef, 2020) to promote courteous communication between learners and educators for a pleasant learning experience. Evaluation of online education can be conducted during the session by performing formative and summative assessment; assessing quality and completion rate of learners’ assignment; analysing learners feedback from the post-session questionnaire as well as learners’ grade during module assessment and performance in the clinic.

Table 1. Netiquette for online education

Note: Adapted from “Computer-based simulation and online teaching netiquette in the time of COVID 19,” by F. Lateef, 2020, EC Emergency Medicine and Critical Care, 4(8), 84-91.

V. MOVING FORWARD

It may take years to return to pre-COVID-19 normalcy, where physical interaction and large gatherings were social norms. Moving forward, we can consider a hybrid or blended learning module alongside limited face-to-face sessions confined to essential skill-based training. However, the effectiveness of online learning compared to traditional modes of clinical teaching has not been elucidated. Dentistry is a practical vocation that requires developing surgical and psychomotor skills to perform specific tasks. Online learning addresses the delivery of didactics but translating theory into practice which involves hands-on skills, teamwork and communication are challenging in the virtual setting. Virtual and augmented reality programmes such as Spatial, coupled with simulation video demonstration, may be suitable for skill-based training in dental education in the virtual environment. Psychological support for faculty and learners and forming a digital technology community of practice among educators can help to improve resilience and coping mechanisms during this challenging period. With safe management measures in place to ensure the well-being of our faculty and learners, we can adapt and continue education activities while looking for innovative ways to deliver clinical teaching effectively in dentistry amidst this pandemic.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Lean Heong Foo is a Consultant Periodontist in the Department of Restorative Dentistry and Head to the Dental Surgery Assistant Certification Programme. FLH reviewed the literature, contributed to the conception, data acquisition, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

Dr Marianne Meng Ann Ong is a Senior Consultant Periodontist & Director of Education in National Dental Centre Singapore. MO contributed to the conception, data acquisition and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

This is a narrative review related to dental education continuity during the COVID-19 pandemic and no ethical approval is required.

Data availability

This paper is a narrative review with no data analysis.

Acknowledgement