Perceptions of clinical year medical students on online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic

Submitted: 22 February 2022

Accepted: 3 August 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 47-50

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/SC2764

Kye Mon Min Swe1 & Amit Bhardwaj2

1Department of Population Medicine, University Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia; 2Department of Orthopaedics, Sengkang General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: During the era of COVID-19 pandemic, online learning has become more prevalent as it was the most available option for higher education training which has been a challenging experience for the students and the lecturers especially in the medical and health sciences training. The study was conducted to determine the perceptions of clinical year medical students on online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: A cross sectional study was conducted to clinical year medical students at University Tunku Abdul Rahman. The validated Online Learning Environment Survey (OLES) was used as a tool to conduct the study.

Results: Total 84 clinical year students participated in the study. Among four domains of OLES questionnaire, the domain; “Support of online learning” had the highest mean perception scores, 4.15 (0.55), followed by “Usability of online learning tools” 3.89 (0.82), and “Quality of Learning; 3.80 (0.68) and the domain “Enjoyment” was the lowest mean perception scores 3.48 (1.08). Most of the students (52.4%) rated the overall satisfaction of online teaching experiences “Very good” while (13.1) % rated “Excellent”.

Conclusion: In conclusion, the perceptions of clinical year medical students on online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic were satisfactory although there were challenging online learning experiences during the pandemic. It was recommended to include qualitative method in future studies to provide more useful in-depth information regarding online learning environment.

Keywords: Online Learning Environment, Perceptions, Medical Students, Malaysia, COVID-19

I. INTRODUCTION

Online learning is defined as learning via web-based technology and students interact with their peers and educators through web-based communication tools (Bonk & Reynolds, 1997). The usability of the web-based learning system is important as are its applications such as interactive video, forums, chat rooms, email, and document sharing systems (Klein et al., 2006).

Online learning is regarded nowadays as a new way of interaction in the educational process and online learning facilities offer various opportunities to get new knowledge and develop students’ skills through engagement and interaction in new learning environments. (Samoylenko et al., 2022)

Due to the novel coronavirus pandemic, all the higher education training has converted to online teaching and assessments including medical programs. To fulfil the student physical learning time requirement, the academic year of MBBS clinical year programmes (Year 3 to Year 5) has been divided into Phase 1; purely online teaching as medical students were not allowed to be posted to hospitals followed by Phase 2; face to face physical clinical training at the hospital. Phase 1 teaching for clinical years include, online task-based learning, online lectures and online case-based discussion, online clinical skill, and procedures. This research study was conducted to evaluate the online learning environment of clinical year students and to find out differences in students’ perceptions between the academic years.

II. METHODS

A cross sectional study was conducted to (total=135) Year 3 to Year 5 clinical year medical students. 43 students were in Year 3, 49 students were in Year 4 and 43 students were in Year 5 at University Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Selangor, Malaysia. All the clinical year students were invited to participate in the study by sending electronic invitations emails, informed consent was taken. Data was collected via google form and the information was anonymised.

A validated Online Learning Environment Survey (OLES) (Pearson & Trinidad, 2005) was used to evaluate the online learning environment of medical students of UTAR during Phase 1 of purely online teaching. The questionnaire consists of two sessions. Section (I) general demographic information, Section (II) contains 50 items of OLES questionnaires developed by Pearson and Trinidad (2005). The validity of the tool was recorded as Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficient value of 0.79 to 0.90. The OLES consists of nine scales: Computer Usage (CU); Teacher Support (TS); Student Interaction & Collaboration (SIC); Personal Relevance (PR); Authentic Learning (AL); Student Autonomy (SA); Equity (EQ); Enjoyment (EN); and A-synchronicity (AS) which can further classified into four domains: (1) Support for learning; (2) Quality of learning; (3) Usability of online learning tools; and (4) Enjoyment. Responses were recorded against a five-point scale with the following representations: 1- Never; 2- Seldom; 3- Sometimes; 4- Often; and 5- Almost Always. (Pearson & Trinidad, 2005)

Data were analysed by using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) for Windows, version 26.0. The categorical variables were described by frequency and percentage. Student t-test and Analysis of variance (Anova) test was used to compare means between the groups of different academic years. Ethical approval was acquired from the Scientific Ethical Review Committee of the UTAR.

III. RESULTS

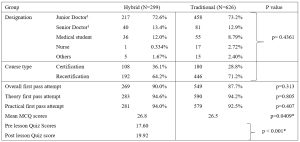

A total of 84 clinical year medical students participated from Year 3 to Year 5. There were 27 out of 43 Year 3 students (62.79%), 26 out of 49 Year 4 students (53.06%), 31 out of 43 Year 5 students (72.09%) who completed the questionnaire. Approximately 82 (97.6%) students were aged between 21 to 25 years and (63.1%) were female students.

The online learning environment survey (OLES) tool consists of four domains to evaluate student online learning environments such as “Support of Online learning”, “Usability of online learning tools”, “Quality of Learning” and “Enjoyment”. Among four domains of OLES tool, the domain; “Support of online learning” had the highest mean perception scores 4.15 (0.55), followed by “Usability of online learning tools” 3.89 (0.82), and “Quality of Learning; 3.80 (0.68) and the domain “Enjoyment” was the lowest mean perception scores 3.48 (1.08).

|

Domains of perceptions of online learning environment |

Subscales of perceptions of online learning environment |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

|

Support for learning |

Computer Usage |

4.24 (0.64) |

4.15 (0.55) |

|

Teacher Support |

4.09 (0.78) |

||

|

Student Interaction and Collaboration |

4.02 (0.78) |

||

|

Equity |

4.25 (0.82) |

||

|

Quality of learning |

Personal Relevance |

3.60 (0.87) |

3.80 (0.68) |

|

Authentic Learning |

3.66 (0.82) |

||

|

Student Autonomy |

4.16 (0.76) |

||

|

Usability of online learning tools |

A-synchronicity |

3.89 (0.81) |

3.89 (0.82) |

|

Enjoyment |

Enjoyment |

3.48 (1.08) |

3.48 (1.08) |

Table 1: The mean perception scores of domains and subscales of online learning environment

Regarding the relation between academic year and student perception on different domains of the online environment, Year 5 students 3.89 (1.01) enjoyed the online learning as compared to Year 3 3.25(0.95) and Year 4 students 3.22 (1.18) respectively and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.027). Year 4 students perceived more positive on domains support of learning (P=0.658) and quality of learning (P=.396) and Year 5 students perceived online learning tools were useful (P=0.681).

The students were asked to rate their online learning experience via 5 points scale, poor to excellent and (52.4%) of the students found online learning experiences very good followed by (29.4%) good and (13.4%) rated excellent. The data for this research can be accessed at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19322297

IV. DISCUSSION

During COVID-19 pandemic era, medical clinical teaching via online was a challenging experience for both clinical lecturers and clinical year students and this study was to determine the perceptions of clinical year medical students on online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A. Evaluating Online Learning Environment

In the literature, there were quite several tools which have been developed to specifically evaluate online learning environments such as Constructivist On-Line Learning Environment Survey (COLLES), Web-Based Learning Environment Inventory (WEBLEI), Technology-Rich Outcomes-Focused Learning Environment Inventory (TROFLEI), and Online Learning Environment Survey (OLES). The OLES instruments have been used to evaluate the university’s online learning environment and found to be a useful tool to evaluate online learning environments as the questionnaires were applicable to our local setting of online teaching. The OLES tool consists of four domains to evaluate student online learning environments such as Support of Online learning, Usability of online learning tools, Quality of Learning and Enjoyment. (Chew, 2015) The scores on scales which received specific attention for online educators to monitor the online learning environment provided for students.

1) Support of online learning: This domain includes four sub scales and it is the most important part for the students to be able to cope with the online learning environment. Regarding support for computer usage, the findings indicate the students received good support from the university regarding online learning such as the providing internet package for students, laptops, online learning tools and platforms such as Microsoft team. The support from lecturers and peers were also important in regarding clinical case discussion and group works. But in some cases, the students need to go and use internet at their relative’s house. On the “Lecturer Support Scale” and “Equity scale”, that the students got support and equivalent chances to contribute in class discussion. (Chew, 2015)

2) Usability of online learning tools: This domain includes asynchronicity subscale. Asynchronicity allows students to learn on their own schedule, within a certain timeframe. In this study, there were high mean scores for the “Asynchronicity” scale which indicates that the students found it easier to communicate online. But the result was contrary to a study by Chew (2015), found out that the students found it challenging to communicate online depends on the availability of internet and usage of social media.

3) Quality of learning: This domain includes three subscales: Personal Relevance, Student Autonomy, and Authenticity learning. The findings indicate that the students were able to manage and play significant roles in their learning in the online learning climates.

4) Enjoyment: The Enjoyment scale was used to evaluate the extent of enjoyment of learning in an online learning environment. Among all four domains, the enjoyment was the least mean perception score which indicated that although the students received support from university and lecturers, they enjoyed less with the online classes as the classes were entirely online. The result was similar to a study by Chew (2015), stated that the students had limited enjoyment in online learning environments due to lack of motivation and technical problems.

B. Limitations of the study

The study was conducted in a private medical university and quantitative approach. A mixed methods approach with larger sample was recommended for future investigations. Validation of the survey recommends carrying out for local setting.

C. Implication of the study

The present study evaluates the online learning environment experienced by clinical year medical students which found to be useful by giving them different learning opportunities and this can be used to implicate future clinical teaching as hybrid mode to create an effective and safe learning environment. The information from this study about the students’ perceptions on online learning, provided significant implications in the field such as implementation of hybrid learning, telemedicine in medical curriculum.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the perceptions of clinical year medical students on online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic were satisfactory although there were challenging online learning experience during the pandemic. It was recommended to include qualitative method in future studies to provide more useful in-depth information regarding online learning environment.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Kye is the corresponding author for this paper. She designed the study, analysed the data, prepared the manuscript working together with the co-author.

Dr Amit Bhardwaj made substantial contributions to the design, editing and preparation of the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The research study was approved by Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman Scientific and Ethical Review committee on 20th July 2020 (Approval number: U/SERC/92/2020).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of the study are openly available at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19322297

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the clinical medical students of UTAR (Academic Year 2020/2021) for voluntary participation in this study.

Funding

There was no funding for this research study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships.

References

Bonk, C. J., & Reynolds, T. H. (1997). Learner-centred web instruction for higher order thinking, teamwork, and apprenticeship. In B. H. Khan (Ed.), Web-based instruction (pp.167-178). Englewood Cliffs.

Chew, R. (2015). Perceptions of online learning in an Australian University: Malaysian students’ perspective – Support for Learning. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 5(8), 587-592. https://doi.org/10.7763/ijiet.2015.v5.573

Klein, H. J., Noe, R. A., & Wang, C. W. (2006). Motivation to learn and course outcomes: The impact of delivery mode, learning goal orientation, and perceived barriers and enablers. Personnel Psychology, 59(3), 665–702. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00050.x

Samoylenko, N., Zharko, L., & Glotova, A. (2022). Designing online learning environment: ICT tools and teaching strategies. Athens Journal of Education, 9(1), 49-62. https://www.athensjournals.gr/education/2022-9-1-4-Samoylenko.pdf

Pearson, J., & Trinidad, S. (2005). OLES: An instrument for refining the design of e-learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21(6), 396- 404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2005.00146.x

*Kye Mon Min Swe

Jalan Sungai Long, Bandar Sungai Long,

43000 Kajang, Selangor

+601115133799

Email: drkyemonfms@gmail.com

Submitted: 29 May 2022

Accepted: 16 August 2022

Published online: 3 January, TAPS 2023, 8(1), 43-46

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-1/SC2807

Kirsty Foster

Academy for Medical Education, Medical School, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Abstract

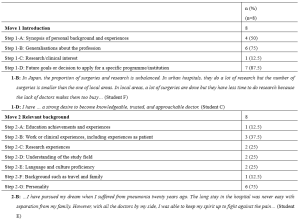

Introduction: A series of workshops was held early in our MD curriculum redesign with two aims: gaining stakeholder input to curriculum direction and design; engaging colleagues in the curriculum development process.

Methods: Workshops format included rationale for change and small-group discussions on three questions: (1) Future challenges in healthcare? (2) our current strengths? (3) Future graduate attributes? Small-group discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed and fieldnotes kept and thematically analysed. We conducted a literature review looking at best practice and exemplar medical programs globally.

Results: Forty-seven workshops were held across 17 sites with more than 1000 people participating and 100 written submissions received. Analysis showed alignment between data from workshops, written submissions and the literature review.

The commitment of our medical community to the education of future doctors and to healthcare was universally evident.

Six roles of a well-rounded doctor emerged from the data: (1) Safe and effective clinicians – clinically capable, person-centered with sound clinical judgement; (2) Critical thinkers, scientists and scholars with a thorough understanding of the social and scientific basis of medicine, to support clinical decision making; (3) Kind and compassionate professionals – sensitive, responsive, communicate clearly and act with integrity; (4) Partners and team players who collaborate effectively and show leadership in clinical care, education and research; (5) Dynamic learners and educators – adaptable and committed to lifelong learning; and (6) Advocates for health improvement – able to positively and responsibly impact the health of individuals, communities and populations

Conclusion: Deliberate stakeholder engagement implemented from the start of a major medical curriculum renewal is helpful in facilitating change management.

Keywords: Medical Education, Medical Curriculum, Stakeholder Engagement, Collaboration

I. INTRODUCTION

The quality of the medical education we provide to future doctors is directly related to the quality of care they will provide to their future patients (Torralba & Katz, 2020). It is the responsibility of those involved and of medical schools to promote the highest standards of medical education and medical student learning. At the University of Queensland, a major reimagining of the MD Program is underway to ensure that our already strong medical program remains informed by best practice in both medicine and in education. This is crucial to enabling our medical graduates to be optimally equipped for their internship, pre-vocational and specialist training. It is our responsibility to enable our graduates to be ready for the future medical needs of the people and communities they serve.

Medical programs are complex and involve many people. As well as University academic and professional staff, medical students are taught, supervised and supported by a wide variety of doctors and other health professionals during the four years of our postgraduate degree. At our university we have approximately 4,500 affiliates who may have a role in teaching, supervising or otherwise influencing one or more medical students at some point during their four-year MD program. Many of these are clinical teachers or supervisors who work for the health services with which UQ has a student placement agreement in place. Cognisant that major curricular review is challenging we implemented a deliberate strategy of engagement with as many of our stakeholders as possible from the start of the MD Design project in 2019. In the first stage we planned a series of engagement workshops with key stakeholders and this is the basis of the study.

The purpose of our study was twofold:

Firstly, to gain input from a wide range of stakeholders early in the process to futureproof our curriculum – that is, to inform the vision on what our graduates need to be able to know, do, and be, to succeed in internship and beyond.

Secondly, to involve our key stakeholders in the curriculum design process as a component of change management.

II. METHODS

A series of stakeholder workshops was held. The format of each workshop was to start with a brief outline of the drivers and rationale for curricular change, followed by small-group interactive discussions focusing on three questions:

- What are the major future challenges in relation to healthcare?

- What are our current strengths as a Medical Program, as a university and as a health community?

- What are the important attributes for our future graduates to achieve to best prepare them for their careers?

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval number 2019001725). At the start of each workshop attendees were provided with information about the study and given the opportunity to withdraw. Their participation in the workshop was regarded as consent. All small-group discussions were overseen by KF, audio-recorded and transcribed. KF and the administrative team kept field notes capturing any elements additional to the spoken word such as the general atmosphere of the workshop. KF and JH analysed the transcripts thematically identifying key elements in each focus area. In parallel a literature review was conducted looking at best practice medical education and exemplar medical programs across the globe were explored.

III. RESULTS

Over a period 15 months between July 2019 and January 2021 47 workshops were held across 17 sites with more than 1100 people participating. More than 100 written submissions were received and 5814 people and organisations contacted. Analysis demonstrated general agreement that major change was needed and there was good alignment between feedback received from stakeholder workshops, written submissions and the key findings from the current state analysis as outlined above. There were some stakeholders who felt that they needed to see more substantial evidence that the current curriculum needed refreshing. This group felt reluctant to embark on further change in view of modifications already made in recent years. They were also concerned that ‘change fatigue’ may be a challenge especially among our health service colleagues who contribute to the program.

A key finding was that the passion and commitment of our medical community to the education of future medical doctors and to make a positive contribution to healthcare was universally evident.

The resulting vision for our new MD program is:

To nurture and educate future medical graduates who are clinically capable, team players, kind and compassionate, serve responsibly and are dedicated to the continual improvement of the health of people and communities in Queensland, Australia and across the globe.

To enhance the capability of our graduates to meet the needs of their future patients a set of six roles of the all-round high-quality doctor was developed from the data. These roles map to the four domains that the Australian Medical Council require for primary medical degrees (Australian Medical Council (AMC), 2012), and have been adopted as the vertical themes of the new MD program. They are:

- Critical thinkers, scientists and scholars who have a thorough knowledge and understanding of the social and scientific basis of medicine, and able to apply evidence and research to inform and support clinical decision making.

- Dynamic learners and educators who continue to adapt, are curious, agile, motivated, self-directed, with the ability to honestly and humbly appraise their own learning needs, and have a commitment to lifelong learning.

- Advocates for health improvement who stand with people and are able to positively and responsibly impact the health of individuals, communities and populations. Are able to apply an understanding of health inequalities to strive for health equity, and incorporates prevention and advocacy into clinical practice in all settings.

- Partners and team players who collaborate effectively and show leadership when appropriate in the provision of clinical care and health-related education and research.

- Kind and compassionate professionals who are sensitive, responsive, communicate clearly and act with integrity. Compassion and professionalism are linked not only to improved patient outcomes but to better practitioner outcomes including job satisfaction and to better institutional outcomes.

- Safe and effective clinicians who are clinically capable, person-centred and demonstrate sound clinical judgement – and who can see that they cannot be safe and effective unless they are also capable in all other roles.

The new MD program is structured as five fully integrated courses, three year-long and two semester long courses in final year, with assessment focused on growth and development of knowledge skills and attitudes through active engagement in learning. Assessment for learning as well as of learning is fundamental in enabling all students to reach their full potential. The project has progressed through development of staged learning outcomes for each year of the program and now into detailed and appropriately sequenced learning activities.

Figure 1. The six roles of a well-rounded doctor

IV. DISCUSSION

Communication throughout a period of major change is challenging especially where there are many diverse stakeholders across a large and complex organisation like a medical school (Velthuis et al., 2018). Our strategy was a deliberate one to retain connection and involvement during a lengthy process. Our initial engagement work reported here gave us a good start by actively involving as many people as possible from the beginning of the project. As the project has progressed stakeholders have remained engaged and have been particularly keen on seeking the detail needed to assist in implementation of the new curriculum. This has, on occasion, been challenging when tension between some specialist discipline areas protecting their ‘patch’ and the needs of medical students at primary medical degree level emerge. We also found that education is not regarded as a specialist field by some of our experienced clinical teachers. A lack of understanding about the iterative process of outcomes-based curriculum development contributed to colleagues seeking answers about what is to be taught being frustrated at what they saw as a laborious process of careful scaffolding and integration. This contesting of curriculum is recognised within institutions where it can inhibit development of more effective curricula which promote learning and are more than simply identification of content to be taught (Prideaux, 2003). By engaging with stakeholders from the earliest stage of the curriculum development process we feel that we have minimised this effect.

V. CONCLUSION

Our experience demonstrates that a deliberate stakeholder engagement strategy implemented from the start of a major curriculum renewal is helpful in maintaining key stakeholder involvement. We found that facilitating a collective discussion about the direction and underpinning values of an innovative medical curriculum was a helpful strategy although some stakeholders felt that, since their wishes had not been adopted, they had not been involved. Despite this, we found that, in most cases, stakeholder involvement from the start led to ongoing collaboration in the change management of implementing a new medical program.

We must ensure that our graduates are optimally prepared to begin their careers as medical practitioners over the next 30 to 40 years, and are ready to meet the needs of the people of Queensland, Australia and globally. We are confident that our early engagement on MD Design will help to achieve that goal.

Notes on Contributors

KF conceptualised, led the workshops where data were collected, contributed to data analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics Approval for the study was obtained from the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee, Application number 2019001725 granted June 2019. Potential participants were provided with study information prior to the workshops and their active participation in the ensuing workshop was taken to indicate consent.

Data Availability

Data is not currently stored in the UQ Data repository because of its nature, as transcripts of meeting discussions where the partipants may be identified would breach the conditions of ethics approval.

Acknowledgement

The curriculum design project described in this study is an endeavour involving a large number of people. The author would especially like to thank Professor Stuart Carney, Dean of the Medical School for his support in many of the engagement sessions, Dr Jane Hallos for her assistance with data collection, analysis and literature review, Ms Alexandra Longworth for assistance in data collection and all workshop participants for their input.

Funding

The study was funded as part of the MD Design project led by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Queensland. There was no specific grant funding but the Mayne Bequest supported medical education research expenses.

Declaration of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

References

Australian Medical Council (AMC). (2012). Standards for assessment and accreditation of primary medical programs by the Australian Medical Council 2012. Australian Medical Council Ltd.

Prideaux, D. (2003). ABC of teaching and learning in medicine: Curriculum design. BMJ, 326(7381), 268-270. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7383.268

Torralba, K. M. D., & Katz, J. D. (2020). Quality of medical care begins with quality of medical education. Clinical Rheumatology, 39, 617-618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04902-w

Velthuis, F., Varpio, L., Helmich, E., Dekker, H., & Jaarsma, A. D. C. (2018). Navigating the complexities of undergraduate medical curriculum change: change leaders’ perspectives. Academic Medicine, 93(10), 1503-1510. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002165

*Kirsty Foster OAM

Academy for Medical Education, Medical School,

Level 6, Oral Health Centre,

288 Herston Road

Herston QLD 4006 Australia

+61 7 3346 4676

Email: Kirsty.foster@uq.edu.au

Submitted: 8 January 2022

Accepted: 26 April 2022

Published online: 5 July, TAPS 2022, 7(3), 51-56

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/SC2738

Yiwen Koh1, Chengjie Lee2, Mui Teng Chua1,3, Beatrice Soke Mun Phoon4, Nicole Mun Teng Cheung1 & Gene Wai Han Chan1,3

1Emergency Medicine Department, National University Hospital, National University Health System, Singapore; 2Department of Emergency Medicine, Sengkang General Hospital, Singapore; 3Department of Surgery, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 4Department of Nursing, National University Hospital, National University Health System, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore, clinical attachments for medical and nursing students were temporarily suspended and replaced with online learning. It is unclear how the lack of clinical exposure and the switch to online learning has affected them. This study aims to explore their perceptions of online learning and their preparedness to COVID-19 as clinical postings resumed.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among undergraduate and graduate medical and nursing students from three local universities, using an online self-administered survey evaluating the following: (1) demographics; (2) attitudes towards online learning; (3) anxieties; (4) coping strategies; (5) perceived pandemic preparedness; and (6) knowledge about COVID-19.

Results: A total of 316 responses were analysed. 81% agreed with the transition to online learning, most citing the need to finish academic requirements and the perceived safety of studying at home. More nursing students than medical students (75.2% vs 67.5% p=0.019) perceived they had received sufficient infection control training. Both groups had good knowledge and coping mechanisms towards COVID-19.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated that medical and nursing students were generally receptive to this unprecedented shift to online learning. They appear pandemic ready and can be trained to play an active part in future outbreaks.

Keywords: Medical Students, Nursing Students, COVID-19, Pandemic, Online Learning, Survey

I. INTRODUCTION

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore, the government implemented safe distancing and movement restriction orders in a bid to flatten the epidemiological curve. These measures from 7th April to 1st June 2020 were coined the “circuit breaker” period. Clinical attachments for medical and nursing students were suspended to lower the risk of COVID-19 transmission and to focus the hospitals’ efforts towards dealing with the outbreak.

Before the pandemic, students were embedded within clinical teams where they received bedside teachings, practised communications with patients and acquired practical skills. Students perceive online learning during the pandemic to be less effective for acquiring clinical skills due to the absence of patient interaction and real-world practice (Wilcha, 2020). As the pandemic situation stabilised in Singapore, healthcare students gradually returned to the hospitals from May 2020. In one study, students were concerned about returning to the clinical settings as they perceived themselves as untrained and worried about the risks they might introduce to patients (Hernández-Martínez et al., 2021). This may arise from a lack of pandemic preparedness, which is not commonly incorporated into the medical and nursing school curriculum.

To date, there are no studies evaluating the perceptions of both local medical and nursing students towards the disruption of their studies by the pandemic, and whether these perceptions would be similar to those cited in the aforementioned study. Specifically, we aim to describe the perceptions of online learning and pandemic preparedness of medical and nursing students in Singapore during the “circuit breaker” period. Understanding this will help us create more effective learning strategies and reinforce their preparation for future pandemics.

II. METHODS

A. Study Design and Setting

This was a cross-sectional survey involving medical and nursing students from Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSOM) and Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies (ALCNS), National University of Singapore (NUS); Duke-NUS Medical School (Duke-NUS); and Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine (LKCSOM), Nanyang Technological University (NTU). Students doing clinical attachments in healthcare institutions during the “circuit breaker” period were sent a link to a self-administered, anonymous online questionnaire. Participation was voluntary. Ethics approval for waiver of written informed consent was obtained from NUS Institutional Review Board (Reference number: NUS-IRB-2020-129).

B. Study Instrument

The questionnaire comprised six parts with a total of 74 questions: (1) socio-demographic characteristics; (2) attitudes towards halting clinical attachments and shift to online learning; (3) anxieties towards the pandemic; (4) coping strategies; (5) perceived pandemic preparedness; and (6) specific knowledge about COVID-19. Responses were collected on Likert scales and the questionnaire was adapted from previous studies with permission. Minor modifications were made to standardise the terms used to refer to COVID-19 and online learning and to ensure understandability in Singapore’s context, while preserving the original intent of the source studies. Content validity of the questionnaire was examined by three board-certified emergency physicians involved in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education.

C. Survey Dissemination

The survey was disseminated to eligible students via email by each school’s administrative staff, who were not part of the study team. Four reminder emails were sent from September to October 2020.

D. Statistical Analysis

Results were analysed using Stata 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Categorical variables were reported as proportions in percentages and analysed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as indicated. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

III. RESULTS

A total of 316 students were recruited between September and December 2020. 64.2% (203/316) were medical students, most of whom were from YLLSOM (147/203, 72.4%). The majority were between 21 and 29 years of age (250/316, 79.1%).

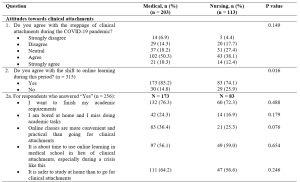

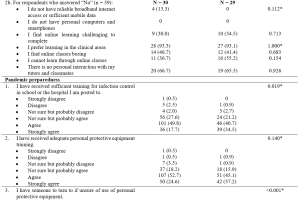

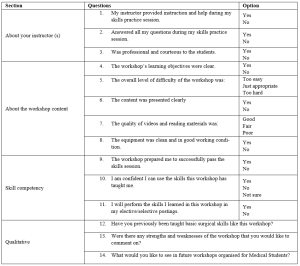

Table 1 details the respondents’ attitudes towards clinical attachment and their perceived pandemic preparedness. Overall, 57% (180/316) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with stopping clinical attachments. 81% (256/316) agreed with the shift to online learning. The two main reasons for preferring online learning were the need to finish academic requirements and the perceived safety of studying at home. Of those who disagreed, most preferred learning in the clinical areas and felt there was a lack of personal interaction with tutors and classmates via online learning.

With regards to pandemic preparedness, more nursing students agreed or strongly agreed they had received sufficient infection control training in school or the hospitals they were posted to (75.2% vs 67.5% p=0.019) and had someone to turn to for advice on the use of personal protective equipment if uncertain (p<0.001), compared to the medical students. They were also more likely to have received influenza vaccination (p<0.001) or were recommended to do so (p=0.020).

More than 70% of students used healthy coping strategies such as participating in relaxation activities and interacting with family and friends for support. More than 90% were aware of the basic facts about COVID-19, such as its origin, symptoms, transmission, and prevention methods. Supplementary tables of the complete survey results have been made openly available online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19646340 .

Table 1. Attitudes towards clinical attachments during Singapore’s circuit breaker period (7 April to 1 June 2020) and their perceived pandemic preparedness

*Fisher’s exact test

Cronbach’s alpha for 9 items of pandemic preparedness = .60

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Paradigm Shift to Online Learning

Our study found that the majority were agreeable with transitioning to online learning during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, given Singapore’s digital connectivity, students in this study did not lack a reliable internet connection or access to technological devices – reasons why students in other countries found virtual teaching challenging (Wilcha, 2020). Among those who disagreed with the transition to online learning, more than 90% indicated they preferred learning in the clinical areas. They were also concerned about the lack of personal interaction with tutors and classmates. These were similar concerns reflected by medical and nursing students in other studies, who felt that online teaching could not adequately replace clinical teachings and learning of practical clinical skills, in the absence of direct patient contact. Lack of physical interaction with tutors and classmates can also result in reduced student engagement levels which may lead to less effective learning (Wilcha, 2020).

To address the perceived weaknesses of online learning, educators worldwide have increasingly adopted novel teaching methods. These include virtual simulations and ward rounds where students can interact with real patients, and simulated set-ups at home for clinical skills practice. In several studies, positive feedback was cited in terms of an increase in medical knowledge, clinical reasoning, and communication skills with these teaching methods (Wilcha, 2020). Our study focused on their perceptions of online learning in the initial phase of the pandemic. As the pandemic persists and with more experience in these innovative ways of online engagement, it is unclear whether the students may view online learning differently now.

It is also uncertain whether online learning is less effective in acquiring knowledge compared to clinical placements. Weston and Zauche (2021) found no difference in standardised assessment scores between nursing students who completed an in-person paediatric clinical practice versus those who used high-fidelity virtual simulation software with pre-briefing and debriefing components. More research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of technology-assisted education in imparting clinical competency compared with traditional bedside teaching.

B. Pandemic Preparedness

In this study, we found most of the medical and nursing students felt they were prepared for the pandemic. However, a greater proportion of nursing students perceived they had received sufficient infection control training or had someone to seek advice on the use of personal protective equipment. More had also received the influenza vaccination or were recommended to do so. A previous study found that nursing students were superior to medical students in hand hygiene performance (Cambil-Martin et al., 2020). This was attributed to curriculum differences and less practical training in the healthcare setting for medical students. Our results may reflect similar curriculum disparities, suggesting a need to narrow this gap in pandemic preparation education.

A systematic review by Martin et al. (2020) found that medical students were keen to assist in responses to pandemics and other global health emergencies, in both clinical and non-clinical roles, citing social responsibility and an obligation to help. Having adequate training and knowledge were some factors encouraging their participation. In this study, we did not directly examine if students were willing to serve in the pandemic should the need arise. They however did demonstrate satisfactory basic knowledge about COVID-19 and had healthy coping strategies. This suggests they may be pandemic-ready and may be recruited to play a more active part in future outbreaks.

C. Limitations

Our study has its limitations. First, the voluntary survey results are subjected to non-response bias. However, the demographics of responders were similar to the entire student body and should be representative of the cohort. Second, a cross-sectional survey does not allow the tracking of changes in responses over time. Third, the results may not be generalisable to other countries at varying stages of socio-economic development. Lastly, the results cannot capture responses outside the pre-set questionnaire. For this, qualitative studies would be required to further explore the impact of COVID-19 on the students’ perceptions towards online learning and pandemic preparedness.

V. CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the education of medical and nursing students in Singapore, causing an unprecedented shift from classroom teaching and bedside clinical attachments to online learning. Although this study demonstrated that medical and nursing students were generally receptive towards this paradigm shift, there is a need to continue implementing and refining online learning methods, especially in teaching clinical skills that are traditionally acquired at the bedside. Additionally, our study found that local medical and nursing students may be pandemic ready and can be trained to take an active part in future outbreaks.

Notes on Contributors

Yiwen Koh reviewed the literature, designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. Chengjie Lee performed data collection, analysed the data and critically revised the manuscript. Mui Teng Chua advised on statistical analysis methods, analysed the data and critically revised the manuscript. Beatrice Soke Mun Phoon performed data collection and critically revised the manuscript. Nicole Mun Teng Cheung designed the study instrument and critically revised the manuscript. Gene Wai Han Chan reviewed the literature, conceptualised the overall design of the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval for waiver of written informed consent was obtained from the NUS Institutional Review Board (Reference number: NUS-IRB-2020-129).

Data Availability

The ethical approval by NUS Institutional Review Board was based on the conditions that only study team members will have access to the raw data that will be stored in a password-protected file. A copy of the survey questions and the additional tables of survey results are openly available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19646340

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the administrative staff of the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Duke-NUS Medical School, Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine and Alice Lee Centre for Nursing Studies for their kind assistance with this study.

Funding

No funding sources were used for this research study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Cambil-Martin, J., Fernandez-Prada, M., Gonzalez-Cabrera, J., Rodriguez-Lopez, C., Almaraz-Gomez, A., Lana-Perez, A., & Bueno-Cavanillas, A. (2020). Comparison of knowledge, attitudes and hand hygiene behavioral intention in medical and nursing students. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 61(1), E9–E14. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2020.61.1.741

Hernández-Martínez, A., Rodríguez-Almagro, J., Martínez-Arce, A., Romero-Blanco, C., García-Iglesias, J. J., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2021). Nursing students’ experience and training in healthcare aid during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Journal of Clinical Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15706

Martin, A., Blom, I. M., Whyatt, G., Shaunak, R., Viva, M., & Banerjee, L. (2020). A rapid systematic review exploring the involvement of medical students in pandemics and other global health emergencies. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.315

Weston, J., & Zauche, L. H. (2021). Comparison of virtual simulation to clinical practice for prelicensure nursing students in pediatrics. Nurse Educator, 46(5), E95–E98. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000946

Wilcha, R. J. (2020). Effectiveness of virtual medical teaching during the COVID-19 crisis: systematic review. JMIR Medical Education, 6(2), e20963. https://doi.org/10.2196/20963

*Chengjie Lee

110 Sengkang East Way,

Singapore 544886

Email: lee.chengjie@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 7 June 2021

Accepted: 20 January 2022

Published online: 5 July, TAPS 2022, 7(3), 46-50

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/SC2715

Pilane Liyanage Ariyananda, Chin Jia Hui, Reyhan Karthikeyan Raman, Aishath Lyn Athif, Tan Yuan Yong, Muhammad Hafiz

International Medical University, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: We aimed to find out how medical students coped with online learning at home during the COVID 19 pandemic ‘lockdown’.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was carried out from July to December 2020, using an online SurveyMonkey Questionnaire®, with four sections: biodata; learning environment; study habits; open comments; sent to 1359 students of the International Medical University, Malaysia. Responses of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree and strongly agree for the closed-ended questions on the learning environment and study habits, were scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Percentages of responses were obtained for the closed ended questions.

Results: There were 323 (23.8%) responses. This included 207 (64%) students from the preclinical semesters 1 – 5 and 116 (36%) students from clinical semesters 6 – 10. Of the respondents, more than 90% had the necessary equipment, 75% had their own personal rooms to study, and 60% had satisfactory internet connections. Several demotivating factors (especially, monotony in studying) and factors that disturbed their studies (especially, tendency to watch television) were also reported.

Conclusion: Although more than 90% of those who responded had the necessary equipment for online learning, about 40% had inadequate facilities for online learning at home and only 75% had personal rooms to study. In addition, there were factors that disturbed and demotivated their online studies.

Keywords: Online Learning, Self-directed Learning, Self-regulated Learning, Learning Environment, Malaysian Medical Students

I. INTRODUCTION

In response to the COVID 19 pandemic, the government of Malaysia imposed a movement control order which is referred to as a lockdown, on 18, March 2020. The International Medical University (IMU), which is a private medical university in Malaysia has been relatively resourceful with respect to e-learning even before the occurrence of the lockdown as it had Moodle®, an online Learning Management System (LMS) platform, in its e-learning portal. Like most educational institutions, the IMU, within a short period of time, had to shift the teaching and learning process from a face-to-face mode to an online mode using Microsoft Teams® most of the time during the lockdown.

The objectives or our study were: to describe the learning environment and the study habits of undergraduate medical students while attending online learning sessions during the lockdown; to determine whether undergraduate medical students used the online resources to practice clinical skills (such as communication skills, physical examination skills) and to develop clinical reasoning.

II. METHODS

A literature search was done in PubMed and Google Scholar using search words: online learning, self-directed learning, self-regulated learning, and learning environment. Study setting and sample selection: Our study population was undergraduate medical students of the IMU. Sample size was calculated to be 293, using the formula provided by Fluid Surveys (2020), for a population size of 1359, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. A cross-sectional study was carried out using an online SurveyMonkey Questionnaire®, from July to December 2020. As online surveys are well known to have high non-response rates, the questionnaire was sent to all the undergraduate medical students in the IMU, during the lockdown. Data collection and analysis: Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. The questionnaire had four sections: biodata; learning environment; study habits and open comments. There was a total of 12 questions with questions 4, 10 and 11 being closed-ended and having 4, 5 and 14 subsidiary questions, respectively within them. Responses to the closed-ended questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale: strongly disagree; somewhat disagree; neither agree nor disagree; somewhat agree; strongly agree. Percentages of responses were calculated for the closed-ended questions. Data were analysed using software SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation), and summarised, and descriptive statistics are presented.

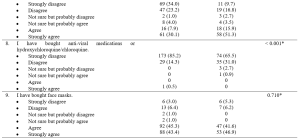

III. RESULTS

Data that support the study are openly available in Figshare at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 16909384 (Ariyananda et al., 2021). 323 students (23.7%) responded. This included 207 (64%) students from the preclinical semesters 1 – 5 and 116 (36%) students from clinical semesters 6 – 10. 75% were in their homes and the remainder were in rented accommodation close to the university. Data mentioned below are summarised in Table 1. More than 98% had either a laptop or a tablet and a smart phone. 93% had Internet and WiFi connections, but the internet connection was stable only for 59.4% and only 64.7% had uninterrupted power supply. The locations of their study areas were as follows: personal room 75%; common ‘living room’15.8%; twin shared room 6.5%; varying locations 2.7%. The following demotivating factors were reported: monotony in studying (70.6%); lack of access to real patients (56.3%); lack of support from peers and mentors (50.5%); inadequacy of e-learning resources (25.7%). In addition, 85.7% reported a variety of other causes as demotivating factors. Factors that distracted were watching television (83.6%); sleeping (55.4%); distractions from other members of the family (40.2%) and house chores (40.2%). For demotivating factors and distractions students were invited to offer one or more responses. Ability to obtain feedback, learn clinical skills, learn clinical reasoning and to prepare for assessments were rated as insufficient (scored as strongly disagree, somewhat disagree or neither agree or disagree) as 55.1, 80.5, 57.2 and 56.6 percent, respectively. Those who strongly agreed or somewhat agreed or neither agreed or disagreed that following issues impair their study performances were: inability to access educational resources physically (62.8%) and deterioration of self-discipline (74.3%).

To determine which online resources were statistically significant with respect to their perception of adequacy to learn and practice clinical skills, an independent sample t test was used to compare the mean score on perception of adequacy of different online resources for 63 (19.5%) students who answered ‘yes’ (strongly agree & somewhat agree) against 260 (80.5%) who answered ‘no’ (strongly disagree, somewhat disagree & neither agree nor disagree). A similar statistical comparison was done regarding learning clinical reasoning during online learning to 138 (42.7%) students who answered ‘yes’, with 185 (57.3%) who answered ‘no’ with respect to perception regarding adequacy of resources. Both comparisons yielded highly significant p values.

|

Statement |

Strongly Disagree n (%) |

Somewhat Disagree n (%) |

Neither Agree nor Disagree n (%) |

Somewhat Agree n (%) |

Strongly Agree n (%) |

|

There was adequate lighting for me to study |

5 (1.5) |

15 (4.6) |

9 (2.8) |

81 (25.1) |

213 (65.9) |

|

I had adequate workspace study |

8 (2.5) |

22 (6.8) |

10 (3.1) |

86 (26.6) |

197 (61) |

|

There were no external distractions around my study |

48 (14.9) |

95 (29.4) |

53 (16.4) |

66 (20.4) |

61 (18.9) |

|

Comfort factor (prepared meals and clean laundry) helped to make a more productive studying environment |

22 (6.8) |

19 (5.9) |

37 (11.5) |

77 (23.8) |

168 (52) |

|

The inability to access resources (textbooks, quiet study environment etc.) from a physical library affected the quality of my studies. |

59 (18.3) |

61 (18.9) |

70 (21.7) |

88 (27.2) |

45 (13.9) |

|

I required supervision from lecturers to effectively study. |

84 (26) |

86 (26.6) |

77 (23.8) |

49 (15.2) |

27 (8.4% |

|

I struggled with self-discipline to concentrate fully on my studies while at home. |

33 (10.2) |

50 (15.5) |

39 (12.1) |

97 (30) |

104 (32.2) |

|

I prefer studying in groups rather than in isolation. |

68 (21.1) |

81 (25.1) |

75 (23.2) |

49 (15.2) |

50 (15.5) |

|

I was able to manage my time better during the lockdown for my studies. |

54 (16.7) |

64 (19.8) |

75 (23.2) |

93 (28.8) |

37 (11.5) |

|

I am confident to use online resources for my studies. |

0 (0.0%) |

19 (5.9%) |

51 (15.8%) |

133 (40.9%) |

120 (37.2%) |

|

IMU e-learning resources were adequate to facilitate my studies. |

17 (5.3) |

37 (11.5) |

88 (27.2) |

131 (40.6) |

50 (15.5) |

|

I was able to navigate my way through IMU e-learning to get the materials required for my studies. |

6 (1.9) |

29 (9) |

60 (18.6) |

143 (44.3) |

85 (26.3) |

|

I found online teaching sessions helpful to me to achieve the learning outcomes. |

20 (6.2) |

44 (13.7) |

89 (27.6) |

109 (33.7) |

61 (18.6) |

|

Scheduled online sessions helped me organize my time for my studies. |

27 (8.4) |

43 (13.3) |

67 (20.7) |

108 (33.7) |

78 (23.8) |

|

Scheduled online sessions helped me motivate myself to do my own self-study. |

32 (9.9) |

48 (14.9) |

75 (23.2) |

99 (30.7) |

69 (21.4) |

|

I was able to participate in online discussions with ease. |

19 (5.9) |

43 (13.3) |

76 (23.5) |

123 (38.1) |

62 (19.2) |

|

I was able to receive relevant feedback from my mentors on my performance through online sessions. |

25 (7.7) |

63 (19.5) |

90 (27.9) |

84 (26) |

61 (18.9) |

|

I was able to learn clinical skills (previously through CSSC sessions / Clinical Postings) through online sessions. |

122 (37.8) |

93 (28.8) |

45 (13.9) |

48 (14.9) |

15 (4.6) |

|

I was able to apply clinical reasoning in cases discussed through online sessions. |

32 (9.9) |

58 (17.6) |

94 (29.7) |

110 (34.1) |

29 (8.7) |

|

I was able to prepare well for assessments through online sessions. |

31 (9.6) |

66 (20.4) |

86 (26.6) |

101 (31.3) |

39 (12.1) |

|

I had stable Internet connection for online sessions. |

30 (9.3) |

44 (13.6) |

57 (17.6) |

108 (33.4) |

84 (26) |

|

I did not experience any power outages which interrupted online sessions. |

19 (5.9) |

61 (18.9) |

34 (10.5) |

81 (25.1) |

128 (39.6) |

Table 1. Information about the online resources and learning environments.

IV. DISCUSSION

Although more than 90% of those who responded had the necessary equipment, about 40 % had inadequate facilities for online learning at home and only 75% had personal rooms to study. This is a substantial minority of students who are not equipped to carry out online learning effectively and it is a matter of concern. Areas that need urgent attention to improve online learning which would cater to 40% that lack facilities are: providing reliable power supply and fortification of web-based infrastructure and services (expansion of internet bandwidth and expansion of WiFi facilities, subsidized access to internet) and subsidizing hardware. It is known that use of the internet by medical students has not translated into improved online learning behaviour (Venkatesh et al., 2017). Previous studies suggest that self-study can be both efficient and inefficient depending on how the learners behave (Evans et al., 2020).

Majority of students strongly agreed and somewhat agreed with regards to adequacy of environmental factors/comforts such as illumination (91%), workspace (96.6%); and prepared meals and clean laundry (75.8%). Studies have shown that temperature, lighting, and noise have significant direct effects on university students’ academic performance (Realyvásquez-Vargas et al., 2020).

Furthermore, there were factors that disturbed and demotivated their online studies such as monotony in studying; lack of access to real patients; lack of support from peers and mentors and inadequacy of e-learning resources. Monotony when studying alone may be overcome by getting students to interact through peer online discussion groups and by providing gamified/interactive learning material online. Gaps due to lack of access to real patients may be reduced by use of photos (especially in dermatology and ophthalmology), images (such as radiographs, CT and MRI scans), video clips (in neurology to demonstrate involuntary movements and seizures), audio clips (to listen to abnormal heart sounds and murmurs) and by studying case scenarios. Examining parents and siblings at home may help to practice clinical examination techniques of different body systems. Role play by teachers and peers on predetermined scripts will help to develop clinical reasoning and communication skills. As non-verbal cues contribute to a great extent in data gathering during history taking, there is a high chance of students missing this aspect, as online learning is two-dimensional compared to three-dimensional experience they would get in real life. Our observations with regards to perceptions on learning clinical reasoning online is better than for learning clinical skills, as many as 42.7% perceive those resources at their disposal as adequate to learn clinical reasoning. This finding may be supported by the understanding that clinical reasoning can be learned without actual physical contact with patients.

However, these methods will not be able to substitute the kinaesthetic experiences of palpating abdominal lumps and uterus (at different stages of foetal development) as well as vaginal examination in normal and diseased states as done in clinical settings. As for learning clinical procedures, although theoretical aspects can be learned remotely, procedural skills cannot be properly acquired without performing in clinical settings. Simulations closely matching clinical settings using artificial intelligence, AR and VR technologies are available and would be further developed in the future.

Limitations: The main limitation of this study is the low response rate of 23.7% despite an email reminder and persuasion by the leader of each cohort. Although the sample exceeded the minimum sample size of 293, the findings may not be generalizable to the rest of the students at the IMU. The study does not address findings specific to different cohorts as subgroup analysis has not been done as sample sizes of cohorts were too small to arrive at valid conclusions. Since majority (64%) of students who responded are from the pre-clinical phase (whose clinical training is much less compared to clinical phase), pooled data regarding ability to learn clinical skills and clinical reasoning online would not be generalizable across all semesters.

V. CONCLUSION

It is concerning to find that 40% did not have stable internet and one-fourth did not have personal study rooms despite 90% possessing hardware. Furthermore, there were factors that disturbed and demotivated online studies. These should be remedied by providing reliable power supply and fortification of web-based infrastructure and services and by providing subsidised hardware.

Although acquisition of clinical reasoning and clinical skills were perceived to be possible, through online teaching/learning sessions, by one in five and two in five students respectively; every possible effort should be made to remedy shortcomings of the remaining students.

As the pandemic is likely to prevail for some time, we recommend further studies, especially to obtain perceptions of medical students studying in other medical schools in Malaysia and in poorly resourced countries and in the subset of clinical students.

Notes on Contributors

Pilane Liyanage Ariyananda contributed to the conception, design of the study, interpretation of data, and preparation of the paper. Chin Jia Hui, Reyhan Karthikeyan Raman, Aishath Lyn Athif, Tan Yuan Yong, Muhammad Hafiz contributed to conception, acquisition and analysis of data.

Ethical Approval

Permission was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (Project ID No.: IMU: CSc/Sem6 (34) 2020) of the IMU to collect and analyse the data.

Data Availability

A copy of the informed consent form, survey questionnaire and anonymized database are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16909384%20 under CC0 license.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to IMU of Malaysia for permitting us to acquire and analyse data and to Professor IMR Goonewardene for his insightful comments on the manuscript. We thank students who participated in the study.

Funding

This work was supported by the International Medical University of Malaysia (Project ID No.: IMU: CSc/Sem6 (34) 2020).

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

References

Ariyananda, P. L., Hui, C. J., Raman, R. K., Athif, A. L., Yong, T. Y., & Hafiz, M. (2021). Online learning during the COVID pandemic lockdown: A cross sectional study among medical students [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 16909384

Evans, D. J. R., Bay, B. H., Wilson, T. D., Smith, C. F., Lachman, N., & Pawlina, W. (2020). Going virtual to support anatomy education: A STOPGAP in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education. 13,279-283. http://doi:10.1002/ASE.1963

Fluid Surveys. (2020). http://fluidsurveys.com/university/survey-sample-size-calculator

Realyvásquez-Vargas, A., Maldonado-Macías, A. A., Arredondo-Soto, K. C., Baez-Lopez, Y., Carrillo-Gutiérrez, T., & Hernández-Escobedo, G. (2020). The impact of environmental factors on academic performance of university students taking online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability, 12(21), 9194. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219194

Venkatesh, S., Chandrasekaran, V., Dhandapany, G., Palanisamy, S., & Sadagopan, S. (2017). A survey on internet usage and online learning behaviour among medical undergraduates. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 93, 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134164

*Pilane Liyanage Ariyananda

Clinical Campus,

International Medical University,

Jalan Rasah, Seremban 70300

Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia

Email: ariyananda@imu.edu.my

Submitted: 26 February 2022

Accepted: 22 April 2022

Published online: 5 July, TAPS 2022, 7(3), 42-45

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-3/SC2766

Gabriel Lee Keng Yan, Lee Yun Hui, Wong Mun Loke, & Charlene Goh Enhui

Faculty of Dentistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Nurturing preventive-minded dental students has been a fundamental goal of dental education. However, students still struggle to regularly implement preventive concepts such as caries risk assessment into their clinical practice. The objective of this study was to identify areas in the cariology curriculum that could be revised to help address this.

Methods: A total of 10 individuals participated and were divided into two focus group discussions. Thematic analysis was conducted, and key themes were identified based on their frequency of being cited before the final report was produced.

Results: Three major themes emerged: (1) Greater need for integration between the pre-clinical and clinical components of cariology; (2) Limited time and low priority that the clinical phase allows for practising caries prevention; and (3) Differing personal beliefs about the value and effectiveness of caries risk assessment and prevention. Participants cited that while didactics were helpful in providing a foundation, they found it difficult to link the concepts taught to their clinical practice. Furthermore, participants felt that they lacked support from their clinical supervisors, and patients were not always interested in taking action to prevent caries. There was also heterogeneity amongst students with regards to their overall opinion of the effectiveness of preventive concepts.

Conclusion: Nurturing preventive-mindedness amongst dental students may be limited by the current curriculum schedule, the prioritisation of procedural competencies, the lack of buy-in from clinical supervisors, and a perceived lack of relevance of the caries risk assessment protocol and should be addressed through curriculum reviews.

Keywords: Dental Education, Caries Risk Assessment, Cariology, Preventive Dentistry, Qualitative Study, Clinical Teaching, Cariogram

I. INTRODUCTION

According to the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019, dental caries in permanent teeth affects an estimated 2 billion people globally yet it is largely preventable. Thus, nurturing preventive-minded dental students has been a fundamental goal of dental education, and a recurring topic of discussion among dental educators (Pitts et al., 2018). Apart from the operative management of dental caries with fillings, dental students are taught to conduct caries risk assessments for their patients. This enables students to construct a tailored caries prevention plan leveraging the use of fluoride varnishes or dietary advice to prevent the onset or progression of carious lesions. However, studies have reported that while students are taught to assess patients’ risk for dental caries and customising preventive plans as part of the Cariology curriculum, they struggle to regularly incorporate prevention into their clinical practice (Calderon et al., 2007; Le Clerc et al., 2021).

The objective of this study was to identify areas in the Cariology curriculum that could be enhanced to help dental students become more prevention orientated in their clinical practice.

II. METHODS

A. Cariology Curriculum at NUS

The Faculty of Dentistry, National University of Singapore offers a four-year Bachelor of Dental Surgery (BDS) programme, mainly divided into pre-clinical and clinical phases. The Cariology curriculum begins in Year 1, where pre-clinical students are equipped with an understanding of the aetiology and pathogenesis of dental caries, along with its preventive and operative management. In Year 2, behavioural science and oral health education and promotion strategies are introduced. Commencing the clinical phase, Year 3 students are taught to utilise the Cariogram electronic assessment tool (D Bratthall, Computer software, Malmö, Sweden), to systematically assess a patient’s caries risk by using self-reported information on plaque control, dietary habits, fluoride exposure, and other caries-related risk factors. From the Cariogram results, a patient’s caries risk profile is generated to guide the development of a targeted caries prevention plan for the patient and aid in the delivery of patient education. A summative assessment is held during the final term of Year 4 where students are required to submit three patient case logs with caries risk assessments and prevention plans documented for one-to-one discussion with faculty members involved in the Cariology curriculum.

B. Study Design

An e-mail invitation was sent to the cohort of 2020 (N=55) within a month after the final examination results were released. Ten individuals responded, willing to participate and giving consent. Participants were divided into two groups where focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted, held on a teleconferencing platform (Zoom Video Communications), facilitated by one study team member using a discussion guide. Audio recordings of the FGDs were transcribed by the facilitator and two other study team members. All the study team members conducted the thematic analysis. Key themes were identified based on their frequency of being cited.

III. RESULTS

Three major themes emerged from the FGDs.

A. Greater Need for Integration between the Pre-clinical and Clinical Components of Cariology

Participants felt that the pre-clinical lectures provided a foundational understanding of dental caries that they could draw from during their clinical phase of training. However, they suggested that the clinical application of Cariology, such as the use of the caries risk assessment (CRA), can be further emphasised at the beginning of the clinical phase of the BDS programme to reinforce its relevance and significance in the context of overall patient care.

“…not really on our mind when we enter clinics. Maybe the staff can run through the CRA assessment forms before entering clinics.”

[P6]

Participants also highlighted that the three cases due in Year 4 could be submitted and discussed with faculty staff earlier in the clinical phase of the course to concretise concepts and allow an opportunity to implement suggested modifications to their patients’ preventive plans.

“But CRA presentation could have been done earlier like in Year 3. Only after the discussion did it really stick in.”

[P10]

“By the time it made sense, clinic was over.”

[P6]

B. Limited Time and Low Priority to Practice Dental Caries Prevention in the Clinical Phase of Training

Participants shared that the main emphasis of a dental student’s limited clinical time was on operative procedures, as it would mean fulfilling clinical competency requirements essential for graduation.

“As students, we’re slow, so we want to maximise time for treatment rather than talking about prevention.”

[P2]

“…there are other more important requirements.”

[P9]

The low priority dental students accorded to dental caries prevention was also influenced by their clinical supervisors. Some participants noted that their clinical supervisors did not appear keen to discuss caries risk assessment findings during the clinical sessions and did not provide guidance on developing caries prevention plans.

“It is just a two-way thing between patients and students, and not with assessors”.

[P3]

“In the clinics no one really checks our caries risk assessments.”

[P1]

Participants also perceived a lack of interest among patients regarding prevention which discouraged them from providing advice.

“Out of the 30 (patients) I saw, only one was interested in oral hygiene instructions and good oral practices.”

[P2]

C. Differing Personal Beliefs about the Value and Effectiveness of Caries Risk Assessment and Prevention

There was a diverse spread of beliefs among participants about the value and effectiveness of caries risk assessment and caries risk management in clinical practice. Several participants saw the value of caries risk assessments and preventive management as necessary tools to help patients prevent the onset and progression of dental caries.

“Caries risk and prevention is what dentistry is about. It would shape preventive strategies and conversations.”

[P10]

“Knowing how to assess risk for the individual is meaningful as it helps employ more time-effective approaches to managing the patient.”

[P5]

Contrastingly, some participants felt that performing caries risk assessments had little added benefit in guiding their preventive advice as,

“…in the end the advice given is the same regardless…”

[P1]

“I didn’t really have to go through the caries risk assessment to tell them what good habits to have.”

[P7]

IV. DISCUSSION

The findings present several perceived barriers that students face from having a more prevention oriented clinical practice. As dental schools focus heavily on procedural competencies, students will place a larger emphasis on fulfilling these requirements and less on assisting their patients with preventive regimes. Furthermore, the duration of the clinical phase of dental training is insufficient to see the results of the preventive advice given, such as a reduction in incidence of new carious lesions, resulting in students finding its impact less meaningful or tangible as compared to placing a filling or extracting a tooth. One solution is to implement formative grading systems in place of the current summative assessments where students would actively identify patients at risk of caries and conduct one-to-one case discussions with their supervisors throughout the clinical phase and be graded accordingly. This system allows for opportunities to reinforce caries prevention concepts and patient management skills throughout the duration of the clinical training instead of only at the end. To address the scepticism some of the students may have with regard to caries risk assessment, steps to address misconceptions may need to be established (Maupome & Isyutina, 2013). A clearer delivery of concepts at the lecture sessions and opportunities during one-to-one case discussions could be implemented in the revised curriculum.

A frequent theme that emerged was the lack of buy-in from the clinical supervisors about carrying out caries risk assessments and preventive management in the student clinics. This may not be surprising as similar sentiments were reported in a recent qualitative study among practising dentists (Leggett et al., 2021). Majority of clinical supervisors are not involved in teaching Cariology and hence it may be necessary to align them with the teaching of caries management paradigms and their roles in informing preventive treatment plans. This can enable them to reinforce such concepts when they supervise the students in the clinics.

The lack of interest in preventive advice among the participants’ patients is similarly observed in other countries – patients know about prevention but are not interested to change (Leggett et al., 2021). Clinical supervisors can encourage dental students to consider different methods of patient engagement through techniques such as Motivational Interviewing, or even take the opportunity to exploit behavioural change models to effect a more pro-prevention lifestyle. In so doing, patients may appreciate better the importance of prevention from various perspectives including the associated cost savings with a reduction in the operative management of dental caries.

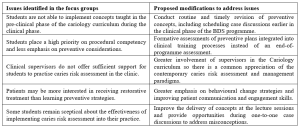

The issues highlighted through the FGDs are summarised in Table 1 together with possible modifications.

Table1. Issues identified in the FGDs and possible mitigating modifications to the current cariology curriculum

V. CONCLUSION

Nurturing preventive-mindedness among dental students may be limited by the current curriculum content and delivery, the prioritisation of procedural competencies, the lack of buy-in from clinical supervisors, and a perceived lack of relevance of the caries risk assessment protocol. Nevertheless, prevention remains the best cure for dental caries and the issues raised through the FGDs can be addressed through curricular modifications discussed earlier. This will, in turn, enhance the preventive-mindedness of the dental students.

Notes on Contributors

GLKY conceptualised the study, participated in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published.

LYH conceptualised the study, participated in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published.

WML conceptualised the study, critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript

CGE designed the methodology, participated in data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the NUS Institutional Review Board (IRB No: S-20-141E).

Data Availability