Entrustable Professional Activities implementation in undergraduate allied health therapy programs

Submitted: 24 January 2023

Accepted: 2 August 2023

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2024, 9(1), 42-48

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2024-9-1/SC2997

Rahizan Zainuldin1 & Heidi Siew Khoon Tan1,2

1Health and Social Sciences Cluster, Singapore Institute of Technology, Singapore; 2Pre-Professional Education Office, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Singapore Institute of Technology’s undergraduate (UG) occupational therapy (OT) and physiotherapy (PT) programs are one of the first implementors of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) in the respective allied health professions training. The aim of the paper is to report the outcomes of the first year of EPAs implementation in clinical practice education (CPE) and share next steps refining implementation.

Methods: A quality improvement (QI) study using the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle was conducted. UG OT Year 2 and Year 3 students, UG PT Year 3 students and their clinical educators (CEs) who experienced the use of EPAs for the first time were surveyed at the end of the clinical block.

Results: There was generally high agreement (>70% agreed or strongly agreed) among all groups in using EPAs to better understand the learning objectives of CPE and practice expectations as future entry-level practitioners at conditional-registration. More than 70% of OT respondents but less than 50% PT respondents found the EPA assessment forms easy to use. Less than 60% of both program CEs did not include colleagues for EPA assessments. 55% of both OT and PT CEs found the EPA training and resources adequate. Overall, PT respondents showed lower agreement than OT respondents in five survey items.

Conclusion: The first implementation cycle of EPA in the undergraduate OT and PT CPE had mixed acceptability to the EPA assessment tools. Three strategic changes were made for the second implementation cycle., i.e., redesign of EPA-based assessment forms, training focus and ‘just-in-time’ training with streamlined resources.

Keywords: Clinical Training, Entrustable Professional Activities, Occupational Therapy, Physiotherapy, Undergraduate, Workplace-based Assessment

I. INTRODUCTION

In 2021, the occupational therapy (OT) and physiotherapy (PT) undergraduate programs at Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) added a novel assessment, Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs), to the extant competency-based assessment tools in clinical practice education (CPE). EPAs are units of professional activities entrusted to a learner determined by five levels of supervision, once the learner has demonstrated the required competence (ten Cate & Taylor, 2020). OT EPAs and PT EPAs (Zainuldin & Tan, 2021) were developed and introduced to SIT CPE as part of the Ministry of Health’s review of healthcare professions’ training standards. EPA-based assessments are relevant in CPE where students perform professional activities at workplace, supervised by onsite clinical educators (CEs). Previous CPEs assessed only OT and PT student competencies using the validated Student Practice Evaluation Form-Revised Edition (SPEF-R) (Turpin et al., 2011) and the Clinical Competency and Reasoning Assessment (CCRA), respectively. Conceptually, the pairing of EPAs with SPEF-R or CCRA potentially offer CEs an opportunity to empower students through graduated levels of entrustment supported by appropriate proficiency levels. Operationally, EPA assessment does not add new activities. OT and PT CEs can utilise routine observations of students’ tasks, case discussions and case-notes documentation as sources to inform entrustment levels in EPAs.

No EPA implementation in any OT and PT curricula has been documented. At SIT, EPA implementation in CPE needs evaluation. Recognising that implementing process changes requires an iterative approach, SIT embarked on a quality improvement study using the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle. This paper reports the results of operationalising EPAs for the first time in OT and PT CPE, including the use of EPA-based assessment forms. The Methods section describes the Plan and Do, followed by the Results section reporting outcomes of the Check and the Discussion section highlighting the Act to improve implementation.

II. METHODS

A. CPE Structure

OT CPE consists of four blocks of seven weeks each and interspersed between academic modules in Years 2, 3 and 4. PT CPE consists of five consequent blocks (four core and one elective) of six weeks each, begins only after all academic modules are completed in Year 3 and continues to Year 4. OT and PT students complete different clinical settings for each CPE block.

B. Participants and Study Design

OT Year 2 and Year 3 students, PT Year 3 students and their CEs who experienced EPA use for the first time were surveyed at the end of a clinical block. An online EPA survey is incorporated with routine post placement feedback for both students and CEs, therefore no consent was required. The QI study was exempt from ethics review (SIT Institutional Review Board, No. 2022122). Survey results were extracted from February to December 2021.

C. PDCA Cycle: Plan-Do

OT and PT have five core EPAs each. EPA-based assessment activities are short practice observations, entrustment-based discussions and case-notes evaluations. These activities serve as sources of information (SOIs), or workplace-based assessments (WBAs) in OT CPE, to inform entrustment decision-making. OT CE assesses EPAs by documenting in a single patient case form with all three WBAs per EPA. PT CE assesses EPAs for every patient case anchored by three different SOI forms with written justifications. OT and PT CEs and students were trained on nuts and bolts of EPAs and on using WBA/SOI forms in CE training workshops and student pre-CPE briefing, respectively.

Each OT EPA requires a total of six patient cases entrusted to students at Level 3 entrustment (indirect supervision) across four CPE blocks. Each PT EPA requires six cases at Level 3 entrustment at each core clinical block, which totals 24 cases by end of the program. Appendix 1 and 2 provides visualisation of EPA implementation across multiple CPE blocks.

The EPA survey has ten items. The first eight items are scored on a 4-point Likert-scale (strongly disagree-strongly agree). The final two questions seek qualitative feedback on benefits and challenges and suggestions for improvements. Unless indicated, items are phrased in the same manner in both student and CE surveys.

D. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were counted as proportions of respondents who agreed (pooled response from ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’) and proportions disagreed (pooled from ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’). The authors grouped the qualitative narrative into benefits and challenges.

III. RESULTS

A. PDCA Cycle: Check

There were 99.0% response rate from OT Year 2 students (105/106), 97.7% from Year 3 OT students (85/87), 93.2% from PT Year 3 students (137/147), 98.5% from OT CEs (199/202) and 92.5% from PT CEs (247/267). Proportion of respondents who agreed with each item statement is shown in Table 1. Data on item scores for each student and CE are available at online repository, http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21941288

|

Survey Items |

OT Year 3 students |

OT Year 2 students |

PT Year 3 students |

OT CEs

|

PT CEs

|

|

(n = 85) |

(n = 105) |

(n = 137) |

(n = 199) |

(n = 247) |

|

|

Q1 – Using EPAs in CPE helps me better understand and meet future conditional-registration requirements.

|

90.6 |

98.1 |

75.2 |

89.4 |

71.7 |

|

Q2 – The EPA documents help me to better understand the learning objectives in CPE.

|

84.7 |

98.1 |

72.3 |

75.9 |

71.7 |

|

Q3 – The WBA/SOI forms are easy to use.

|

76.5 |

85.7 |

38.7 |

73.4 |

47.8 |

|

Q4 – CE: The WBA/SOI forms are adequate for me to determine students’ competence and entrustment level. / Student: The WBAs/SOIs help me to better gauge my progress and level of competence.

|

91.8 |

97.1 |

70.1 |

72.9 |

64.6 |

|

Q5 – I understand the connection between OT EPAs and SPEF-R2 competencies or PT EPAs and CCRA.

|

84.7 |

97.1 |

72.3 |

69.8 |

83.0 |

|

Q6 – CE: I use the EPA documents explicitly with students during clinical teaching and assessment. / Student: I use the EPA documents to guide my learning goals during CPE.

|

62.4 |

92.4 |

51.1 |

87.9 |

59.1 |

|

Q7 – CE: I involve other colleagues in doing WBAs/SOIs to calibrate students’ entrustment level. / Student: Besides my CE, I also received feedback from other OTs or other PTs who were involved in my WBAs/SOIs.

|

44.7 |

66.7 |

54.0 |

58.8 |

45.3 |

|

Q8 – I feel the current briefing/training/resources are adequate for me to incorporate the use of EPAs in CPE. |

70.6 |

89.5 |

56.2 |

55.3 |

55.9 |

Table 1. Proportion of OT and PT students and CEs who agree with the EPA survey items

PT CEs and students were almost unanimous that SOI forms were difficult to use (Q3). Common to OT and PT CEs, many did not involve colleagues in EPAs (Q7) and felt that training to understand EPAs was inadequate (Q8).

Qualitatively, both disciplines benefitted from the use of WBA/SOI forms to scaffold learning through structured feedback and action plans when addressing identified competency gaps. Feedback from OT and PT students below closely exemplified the appreciation:

“EPAs allow me to track my progress over the weeks and transfer my reflections into action when given the opportunity to receive objective and qualitative feedback from the EPA form.”

OT Student#45

“The discussions with the CE on what to do if the situation was different made me realise the importance of planning even for the worst-case scenario…enabled me to identify the gaps in knowledge and skills that had to be worked on.”

PT Student#67

However, PT groups cited complicated forms design and copious paperwork from numerous SOIs time-consuming and stressful. Ambivalence on its practicality was best summed by PT CE#31, “As a first-time user of the SOIs, I found it quite difficult to navigate the forms, took me some tries to understand how I can determine the students’ competence and entrustment level. As there were many forms, it was quite confusing, and hence stressful and time-consuming. Otherwise, they are useful tools.”

The most common challenge among OT CEs was assessing certain EPAs, such as planning care transition, in some settings. “Some EPAs are harder to do in some settings, for example, in the hands therapy setting; it is harder to do the handover/discharge EPA as there are less of these patients.” (OT CE#32). Calling for more support, one CE suggested “SIT go through a round of training on the different EPAs and give relevant case examples to help us better understand them.” (OT CE#4).

IV. DISCUSSION

Response rates were excellent. The convergence of high agreement rates with narrative feedback on using EPAs and WBA/SOIs for teaching/learning, understanding the CPE learning objectives and meeting practice expectations as future entry-level practitioners suggest early indication that EPAs may facilitate SIT OT and PT students transit to new practitioners. The positive experience in this regard resonated with other EPA survey on final-year dietetics students and their clinical supervisors in Australia (Bramley et al., 2021). Practical challenges with the SOI forms, resulting in onerous and time-consuming evidence collection; low levels in involving colleagues in EPA assessments; and inadequate EPA training/resources for CEs were identified as key areas for change in both disciplines.

A. PDCA Cycle: Act

First, to reduce assessment burden, WBA and SOI forms were redesigned and harmonised in preparation towards a standardised EPA online assessment system currently developed in-house. Multiple WBA/SOI forms were combined into a single-page checklist form with a small open-ended section. A checklist was similarly suggested for nursing EPAs assessment, citing convenience as a reason (Lau et al., 2020). On the single-page form, CEs tick entrustment levels for each WBA/SOI associated to each EPA with all EPAs on the same page. The only narrative section is where CEs describe key justifications supporting their entrustment decisions, followed by students’ reflections. Second, to bridge assessment expectations among clinicians and increase propensity to share EPA assessments with colleagues, EPA training was refined to emphasise balance of supervision control with autonomy and clearer definitions between entrustment levels 2 (direct supervision) and 3 (indirect supervision) through case examples. Third, ‘just-in-time’ refresher training was added to activate volition in assessing EPAs. Toolkits containing briefing videos and streamlined resources in short bites, such as 3-minute videos, powtoons, form samplers and frequently-asked-questions, were released for OT and PT CEs closer to placement block. PT CEs also received a refresher at early weeks of every placement block.

V. CONCLUSION

The PDCA cycle is used to inform and make iterative adaptations to each cycle of EPA implementation. The Plan-Do stage completed the first implementation cycle of EPA in the undergraduate OT and PT CPE in 2021. The Check stage revealed mixed experiences to EPA use. The lowest agreement was the ease of using SOI forms among PT students and CEs. While EPAs were accepted as teaching and learning tools, CEs did not involve colleagues in EPA assessments. Training on EPA assessment for CEs was inadequate. Consequently, the Act stage yielded changes in form design, training focus and streamlined resources for the next implementation cycle.

Notes on Contributors

Rahizan Zainuldin (RZ) led the design of the quality improvement and implementation of EPAs, submitted the study to SIT IRB, analysed and interpreted both quantitative and qualitative data for the PT CPE, prepared the manuscript, wrote the initial draft and finalised for submission.

Heidi Siew Khoon Tan (HSKT) led the design of the EPA survey, analysed and interpreted both quantitative and qualitative data for the OT CPE, provided a critical review of the manuscript, and concurred on the final version.

Ethical Approval

The QI study was exempt from ethics review (SIT Institutional Review Board, No. 2022122).

Data Availability

Data on item scores for each student and CE are available at online repository, publicly accessed at http://doi.org/ 10.6084/m9.figshare.21941288. While the data is available for readers’ perusal and no permission from the authors is needed, please write an email of intention to use the data for any purposes to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the OT and PT CPE committee members who have contributed in the planning and implementation of the EPA. We would also like to thank Ms Annie Wang Haiyan, Manager, Academic Programmes Administration, SIT, for uploading the survey on and extracting the survey results from the online assessment portal of our Clinical Practice Education portal.

Funding

No funding source is provided.

Declaration of Interest

Rahizan Zainuldin and Heidi Siew Khoon Tan disclose there is no conflict of interest of any form.

References

Bramley, A. L., Thomas, C. J., McKenna, L., & Itsiopoulos, C. (2021). E-portfolios and entrustable professional activities to support competency-based education in dietetics. Nursing and Health Sciences, 23(1), 148-156. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12774

Lau, S. T., Ang, E., Samarasekera, D. D., & Shorey, S. (2020). Evaluation of an undergraduate nursing entrustable professional activities framework: An exploratory qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 87, Article 104343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104343

ten Cate, O., & Taylor, D. R. (2020). The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No. 140. Medical Teacher 43(10), 1106-1114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1838465

Turpin, M., Fitzgerald, C., & Rodger, S. (2011). Development of the Student Practice Evaluation Form Revised Edition Package. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(2), 67-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00890.x

Zainuldin, R., & Tan, H. Y. (2021). Development of entrustable professional activities for a physiotherapy undergraduate programme in Singapore. Physiotherapy, 112, 64-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2021.03.017

*Rahizan Zainuldin

10 Dover Road,

Singapore 138683

+6596522418

Email: Rahizan.Zainuldin@singaporetech.edu.sg

Submitted: 18 February 2023

Accepted: 28 March 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 40-45

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/SC3010

Kit Mun Tan1, Chan Choong Foong2, Donnie Adams3, Wei Han Hong2, Yew Kong Lee4 & Vinod Pallath2

1Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 2Medical Education and Research Development Unit (MERDU), Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 3Department of Educational Management, Planning and Policy, Faculty of Education, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 4Department of Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: The global COVID-19 pandemic had greatly affected the delivery of medical education, where institutions had to convert to remote learning almost immediately. This study aimed to measure undergraduate medical students’ readiness and factors associated with readiness for remote learning.

Methods: A cross-sectional quantitative study was conducted amongst undergraduate medical students using the Blended Learning Readiness Engagement Questionnaire, during the pandemic where lessons had to be delivered fully online in 2020.

Results: 329 students participated in the study. Mean scores for remote learning readiness were 3.61/4.00 (technology availability), 3.60 (technology skills), 3.50 (technology usage), 3.35 (computer and internet efficacy), and 3.03 (self-directed learning). Male students appeared more ready for remote learning than females, in the dimensions of self-directed learning and computer and internet efficacy. Students in the pre-clinical years showed a lower level of readiness in the technology availability domain compared to clinical students. The lowest score however was in the self-directed learning dimension regardless of the students’ year of studies.

Conclusion: The pandemic had created a paradigm shift in the delivery of the medical program which is likely to remain despite resumption of daily activities post-pandemic. Support for student readiness in transition from instructor-driven learning models to self-directed learning models is crucial and requires attention by institutions of higher learning. Exploring methods to improve self-directed learning and increase availability of technology and conducting sessions to improve computer and internet efficacy can be considered in the early stages of pre-clinical years to ensure equitable access for all students.

Keywords: Remote Learning, Student’s Readiness, Medical Education

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic and global emergency from the end of January 2020 had greatly affected the education sector, with many institutions including undergraduate medical schools converting to remote learning within a short timeframe.

Previous studies have shown that e-learning methods were effective and acceptable among medical undergraduate students (Chen et al., 2020). Studies have also suggested that students may struggle in adapting to a self-directed learning process (Vaughan, 2007), prefer traditional face-to-face lectures and possibly lacking the technological skills and infrastructure for a satisfactory remote learning experience.

It is important to determine the remote learning readiness of undergraduate medical students to facilitate the adaptation of these practices to maximise student competencies. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to determine the readiness for remote learning in undergraduate medical students in a South-East Asian university and the secondary objective was to identify factors associated with their remote learning readiness.

II. METHODS

This was a cross-sectional quantitative study to measure medical students’ readiness towards remote learning using the BLREQ questionnaire. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Reference UM.TNC2/UMREC-889) of the university.

In the Covid-19 enforced scenario at that time, the physical face-to-face teaching in our institution was moved to online almost immediately, requiring the students to adapt their learning approaches rapidly to suit the needs of a virtual learning environment.

The duration of the study was one month, from the 19th of June to the 19th of July 2020. Our country implemented a national lockdown (and emergency remote learning) due to COVID-19 on the 18th of March 2020. Thus, data collection occurred in the first few months of the remote learning situation and represented students’ experiences and readiness during the early phase of the change.

The students were from all five years of study in the medical undergraduate program. They were contacted via their online educational platform and WhatsApp group chats with details of the study, participant’s consent form, link to the online self-administered questionnaire and weekly reminders to encourage participation. Participation was voluntary and consent was obtained from the students. Data were anonymised and not traceable to a particular individual.

This study utilised Section A and B of the BLREQ questionnaire which is a validated questionnaire on the readiness and engagement of students in blended learning (Adams et al., 2018). Although ‘Blended Learning’ is defined as a combination of e-learning (online) and traditional education (face-to-face) approaches, the BLREQ is appropriate for this study as it primarily measures students’ readiness for remote learning. Section A contained basic demographic questions (i.e., age, gender, year of study). Section B had 37 items in five dimensions which addressed various aspects of students’ readiness for remote learning. A 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4) was provided with only one response allowed per item.

The data was analysed using IBM SPSS version 25. The data was non-normally distributed; hence the Mann-Whitney U test was used to test for significant difference in scores between gender and stages of study.

III. RESULTS

There were 329 complete responses out of 734 invited participants (44.8% response rate). Most respondents were aged between 20 to 24 years old (Mean=21.9; SD=1.8). Approximately 59% were female and 59% were clinical students.

The total dimension and individual item mean scores are reported in Table I with the highest and lowest scores of each dimension annotated. The dimensions of remote learning readiness arranged in descending order of total mean score are Technology Availability (3.61+50), Technology Skills (3.60+.43), Technology Usage (3.50+.44), Computer and Internet Efficacy (3.35+.49), and Self-directed Learning (3.03+.51) (Table 1). Research data of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21443100

Analysed by gender, the mean scores of male students were significantly higher than female students in the dimensions of Self-directed Learning; 3.13 vs 2.96 (U=10354.5, z=-3.18, p=.001), and Computer and Internet Efficacy; 3.39 vs 3.32 (U=11332.5, z=-2.02, p=.044). Individual items in which male students scored significantly higher in each dimension were [SDL1], [SDL4], [CIE2] and [CIE3].

When comparing between stages of study, the mean score of clinical students was significantly higher than pre-clinical students only in the Technology Availability dimension; 3.65 vs 3.55 (U=11376.0, z=-2.13, p=.034) An individual item which clinical students scored significantly higher in Technology Availability dimension was [TA3].

|

Dimensions and items |

Mean |

SD |

|

[TS] Technology Skills dimension |

3.60 |

.43 |

|

[TS1] I know the basic functions of a computer/laptop and its peripherals like the printer, speaker, keyboard, mouse etc.** |

3.76 |

.45 |

|

[TS2] I know how to save and open documents from a hard disk or other removable storage device. |

3.67 |

.52 |

|

[TS3] I know how to open and send email with file attachments. |

3.72 |

.48 |

|

[TS4] I know how to log on to Wi-Fi |

3.74 |

.46 |

|

[TS5] I know how to navigate web pages (go to next or previous page). |

3.68 |

.50 |

|

[TS6] I know how to download files using browsers (e.g., Google Chrome, Internet Explorer, Firefox) and view them. |

3.67 |

.51 |

|

[TS7] I know how to access an online library or database.* |

3.19 |

.78 |

|

[TS8] I know how to use Word processing software (e.g., Microsoft (MS) Word). |

3.62 |

.53 |

|

[TS9] I know how to use Presentation software (e.g., MS PowerPoint). |

3.60 |

.53 |

|

[TS10] I know how to use Spreadsheet software (e.g., MS Excel). |

3.30 |

.75 |

|

[TS11] I know how to open several applications at the same time and move easily between them. |

3.60 |

.60 |

|

[TU] Technology Usage [TU] dimension |

3.50 |

.44 |

|

[TU1] I often use the internet to find information.** |

3.86 |

.37 |

|

[TU2] I often use e-mail to communicate.* |

2.93 |

.93 |

|

[TU3] I often use office software (e.g., MS Word, PowerPoint, Excel). |

3.62 |

.56 |

|

[TU4] I often use social networking sites to share information (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat). |

3.39 |

.83 |

|

[TU5] I often use instant messaging (e.g., WhatsApp, Viber, WeChat, Line, Telegram). |

3.72 |

.54 |

|

[TU6] I often use cloud-based file hosting services to store or share documents (e.g., Google Drive, Dropbox, One drive). |

3.44 |

.69 |

|

[TU7] I often use learning management systems (e.g., Blackboard, Moodle). |

3.28 |

.69 |

|

[TU8] I often use mobile technologies (e.g., Smartphone, Tablet) to communicate. |

3.72 |

.51 |

|

[TA] Technology Availability dimension |

3.61 |

.50 |

|

[TA1] I have a computer/laptop with an internet connection.** |

3.74 |

.53 |

|

[TA2] I have a computer/laptop with adequate software for learning (e.g., Microsoft (MS) Office). |

3.63 |

.57 |

|

[TA3] I have speakers for courses with video presentations.* |

3.50 |

.72 |

|

[TA4] I have a computer/laptop and its peripherals like the printer, speaker, keyboard, mouse etc. |

3.57 |

.66 |

|

[SDL] Self-directed Learning dimension |

3.03 |

.51 |

|

[SDL1] I am a highly independent learner. |

3.12 |

.69 |

|

[SDL2] I am able to learn new technologies.** |

3.60 |

.55 |

|

[SDL3] I do not need direct lectures to understand materials.* |

2.36 |

.92 |

|

[SDL4] I would describe myself as a self-starter in learning using technology. |

3.18 |

.79 |

|

[SDL5] I am not distracted by other online activities when learning online (e.g., Facebook, Gaming, Internet surfing). |

2.42 |

1.04 |

|

[SDL6] I can read the online instructional materials on the basis of my needs. |

3.49 |

.58 |

|

[CIE] Computer and Internet Efficacy dimension |

3.35 |

.49 |

|

[CIE1] I feel confident in using online tools (e.g., email, internet chat, instant messenger) to communicate effectively with others. |

3.48 |

.65 |

|

[CIE2] I feel confident in expressing myself (e.g., emotions and humour) in my university’s learning management systems (e.g., Blackboard, Moodle) |

2.89 |

.83 |

|

[CIE3] I feel confident in posting questions in online discussions.* |

2.87 |

.82 |

|

[CIE4] I feel confident in performing the basic functions of Word processing software (e.g., MS Word). |

3.59 |

.55 |

|

[CIE5] I feel confident in performing the basic functions of Presentation software (e.g., MS PowerPoint). |

3.48 |

.62 |

|

[CIE6] I feel confident in performing the basic functions of Spread sheet (e.g., MS Excel). |

3.26 |

.78 |

|

[CIE7] I feel confident in using web browsers (e.g., Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox) to find or gather information for online learning.** |

3.67 |

.53 |

|

[CIE8] I feel confident in using computer or tablet or mobile phone for online learning. |

3.56 |

.63 |

Table 1. Dimension and individual item mean scores of student readiness to engage in remote learning

** highest score in the dimension

*lowest score in the dimension

IV. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to identify medical students’ readiness for remote learning across five dimensions and to identify factors associated with their readiness during the early months of the COVID-19 online learning transition period. Although there is significant resumption of usual activities post-COVID-19 pandemic, many of the online and self-directed components of learning are likely to remain as the way forward in the medical curriculum. Therefore, we feel that this study still has relevance currently.

All mean scores of the subscales Technology Availability (TA), Technology Skills (TS), Technology Usage (TU), Computer and Internet Efficacy (CIE) and Self-directed Learning (SDL), were above 3 on a scale of 1 to 4. The mean scores in our study were much higher and have less deviation than Adams et al’s study conducted in a similar setting before the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the five dimensions scored lower than 3.00, with SDL scoring the lowest mean in the other study at 1.25+1.55 (Adams et al., 2018). Adams et al’s study also did not show much difference when comparing between medicine, social science, science and engineering students (Adams et al., 2018), indicating that readiness for online learning was much lower overall pre-COVID-19.

Despite the increase compared to Adams et al’s study, SDL still scored the lowest in our study out of the five dimensions. An implication of this is that universities need to help learners transition from facilitator/ instructor-driven learning models to self-directed learning models. This can be done by making training in ‘learning to learn’ (L2L) an essential component of student support. In our setting, this training should address items which scored lowest in SDL as these indicate areas of struggle for students; [SDL3] and [SDL5]. It is also possible that some facilitators are not aware of what SDL is, therefore facilitators can also benefit from training for SDL methods.

Our study demonstrated significantly higher readiness for remote learning among male students in comparison to female students in the domains of SDL and CIE. While some studies indicate no gender differences in e-Learning readiness, other studies also report gender differences such as males having more positive attitudes toward online learning; males being more ready for online learning (Adams et al., 2018) and males using more learning strategies and having better technical skills than females (Alghamdi et al., 2020). In the CIE domain, males scored higher in the items [CIE2] and [CIE3] which are both related to communication through a virtual platform. This resulted in males scoring higher in the CIE domain in general. The gender disparity in remote learning readiness needs to be addressed as female students are increasingly the majority (and therefore primary stakeholders) in medical schools worldwide.

The mean score of clinical students was significantly higher than pre-clinical students only in the Technology Availability domain with clinical students reporting better hardware and infrastructure access compared to pre-clinical students. It is likely that as the learners progress through a course, they become more aware of the technological requirements of the course and invest in better devices and internet access. It is also possible that the students’ socioeconomic status at the beginning of their course may not have been good, for example if they were awaiting scholarships to be processed, which subsequently became available later in their course of study. This may have then enabled the students to purchase better hardware and infrastructure further on in their course, during the clinical years. However, this financial aspect was not included our study. It is still worth considering future programs early in the course, where there could be subsidies for students to purchase necessary technological equipment for their studies.

A. Limitations and Recommendations

One limitation of this study was that it looked at remote learning in general and did not look at clinical elements such as using online simulated patients for history taking classes, or procedural skills videos. The study also only looked at student perspectives, and not faculty perspectives to get a complete picture of the online learning experiences. Future studies should explore student readiness for clinical online learning as this would be a struggle for students even if the transition was under normal circumstances (Vaughan, 2007). The perspectives of faculty members on readiness to move towards online learning also need to be explored. The strength of this study was that it used a previously validated questionnaire which allowed some comparison on students’ remote learning readiness with pre-COVID-19 studies.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the study explored medical undergraduates’ remote learning readiness in a public medical school in Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, students were found to be ready for remote learning. However, the lowest scores were for the domain of self-directed learning and computer and internet efficacy. Based on our findings, we feel that support for student readiness in transition from instructor-driven learning models to self-directed learning models is crucial and requires attention by institutions of higher learning. Exploring methods to improve self-directed learning and increase availability of technology and conducting sessions to improve computer and internet efficacy can be considered in the early stages of pre-clinical years to ensure equitable access for all students. There should also be efforts to train the educators to develop online learning activities which incorporate the socio-relational aspects of learning into the remote learning experience.

Notes on Contributors

Kit Mun, Tan is the first author and person who initiated the study, contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, writing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Chan Choong, Foong contributed to the design of study, data collection and analysis, writing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Donnie, Adams is the creator of the original Blended Learning Readiness Questionnaire (BLREQ) and contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, writing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Wei Han, Hong contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, writing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Yew Kong, Lee contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, writing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Vinod, Pallath is the corresponding author and contributed to the design of the study, data collection and analysis, writing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This study received ethical approval from the Universiti Malaya Ethics Review Committee with the approval number of UM.TNC2/UMREC-889.

Data Availability

Research data of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21443100.

Readers may access the anonymised data freely with the above URL. Kindly contact the authors for permission if you wish to use the data for a subsequent study or collaboration.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge and express gratitude to the undergraduate medical students who took the time to participate in this study.

Funding

There was no external funding for this study.

Declaration of Interest

All the authors do not have a conflict of interest to declare.

References

Adams, D., Sumintono, B., Mohamed, A., & Mohamad Noor, N. S. (2018). E-learning readiness among students of diverse backgrounds in a leading Malaysian higher education institution. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 15(2), 227-256. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2018.15.2.9

Alghamdi, A., Karpinski, A. C., Lepp, A., & Barkley, J. (2020). Online and face-to-face classroom multitasking and academic performance: Moderated mediation with self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and gender. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 214-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.018

Chen, J., Zhou, J., Wang, Y., Qi, G., Xia, C., Mo, G., & Zhang, Z. (2020). Blended learning in basic medical laboratory courses improves medical students’ abilities in self-learning, understanding, and problem solving. Advances in Physiology Education, 44(1), 9-14.

Vaughan, N. (2007). Perspectives on blended learning in higher education. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(1), 81-94. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/6310/

*Associate Professor Dr Vinod Pallath

Medical Education Research and Development Unit,

Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya,

50603 Kuala Lumpur

Email: vinodpallath@um.edu.my

Submitted: 9 February 2023

Accepted: 22 March 2023

Published online: 3 October, TAPS 2023, 8(4), 36-39

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-4/SC3000

Komson Wannasai1, Wisanu Rottuntikarn1, Atiporn Sae-ung2, Kwankamol Limsopatham2, Wiyada Dankai1

1Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand; 2Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Abstract

Introduction: Global medical and healthcare education systems are increasingly adopting team-based learning (TBL). TBL is an interactive teaching programme for improving the performance, clinical knowledge, and communication skills of students. The aim of this study is to report the learning experience and satisfaction of participants with the TBL programme in the preclinical years of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University.

Methods: Following the implementation of TBL in the academic year 2022, we asked 387 preclinical medical students, consisting of 222 Year 2 and 165 Year 3 medical students who attended the TBL class to voluntarily complete a self-assessment survey.

Results: Overall, 95.35% of the students were satisfied with the structure of the TBL course and agreed to attend the next TBL class. The overall satisfaction score was also high (4.44 ± 0.627). In addition, the students strongly agreed that the TBL programme improved their communication skills (4.50 ± 0.796), learning improvement (4.41 ± 0.781), and enthusiasm for learning (4.46 ± 0.795).

Conclusion: The survey findings indicated that students valued TBL-based learning since it enabled them to collaborate and embrace learning while perhaps enhancing their study abilities. However, since this is a pilot study, further investigations are warranted.

Keywords: Team-based Learning, Small Group Interaction, Medical Education, Implementation

I. INTRODUCTION

Team-based learning (TBL) is a form of small-group teaching which can improve student performance, clinical knowledge, and communication skills. It has been employed in medical and healthcare education in the US, Australia, Austria, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore (Burgess et al., 2014; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). Since 2000s, this model has been used in medical education to foster deep learning across a variety of subjects and educational contexts, benefiting teachers and helping academically weak and strong students achieve the same or better results than with conventional methods (Parmelee et al., 2012). In addition, it is more effective for engaging students than lecturing in a large class with few teachers (Burgess et al., 2020b).

The key elements of TBL include pre-class preparation to encourage self-study, teamwork, and instant feedback. These key elements promote active learning and critical thinking (Burgess et al., 2020a; Parmelee et al., 2012). The steps in TBL include pre-class preparation, individual readiness assurance test (iRAT), team readiness assurance test (tRAT), feedback, and team application (Burgess et al., 2014). In the tRAT and team application phase, students work in small groups to demonstrate the use of teamwork for problem-solving. Clinical problem-solving exercises by students lead to class discussions and instructor comments (Burgess et al., 2020a; Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). The teacher’s feedback can help clarify students’ responses by discussing their answers. In the academic year 2022, TBL was implemented on second- and third-year medical students in the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, and self-assessment questionnaires were used to assess students’ satisfaction with the TBL model. This research aims to examine the impact of team-based learning on whether or not students were able to build their own learning processes, as well as to measure student satisfaction with teaching and learning in the TBL paradigm in order to improve further TBL classrooms in the faculty.

II. METHODS

A. Sampling and Participants

In 2022, 387 pre-clinic medical students from Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Medicine were studied (222 from Year 2 and 165 from Year 3). Year 2 medical students studied human skin and the connective tissue system, while Year 3 medical students studied human haematology. Each TBL class consisted of 50 teams of mixed-gender and grades. Each team contained five members.

B. Structure and Components of TBL

The TBL programme was first implemented in the 2022 academic year, covering preclinical academic Years 2 and 3 at the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. The TBL structure comprised two major phases: pre-class and in-class. The TBL topics included automated haematology and venomous snakes for Year 3 medical students. The skin infection topic was selected for Year 2 medical students.

After TBL, the non-researcher academic team informed medical students about the study and sought volunteers to avoid a conflict of interest between the instructors and the medical students. The non-researchers urged students interested in the experiment to complete a Google Forms questionnaire outlining the study’s relevance, including an explanation of the topic, data gathering, and the pros and cons of participation. If participants agreed to answer the questionnaire, they could complete the Google Form to consent and submit the questionnaire, with their personal information remaining anonymous.

For validity, a questionnaire to explore students’ views on TBL was prepared via a literature study, student review (two students), peer review (faculty members from two departments), and expert opinion (a TBL expert). It also examined students’ perceptions of teams and their beliefs and values in collaboration. The outcomes of the different years of student were then compared.

C. Data Collection and Analysis

Upon completing the TBL class, participant students were invited to voluntarily take the self-assessment survey to explore their thoughts on the assertions made in the TBL literature. The questionnaire was in Thai and we used a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly dissatisfied, 2 = unsatisfied, 3 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4 = satisfied, 5 = strongly satisfied). Students were asked about the preparation for the TBL class, including student material, classroom, teaching content, self-preparation, orientation programme, class material, and the overall programme. The self-assessment survey also asked about promoting self-understanding, including communication skills, learning improvement, and enthusiasm in learning using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

The TBL self-assessment survey data were analysed according to mean and standard deviation (SD) using STATA version 16 (STATA Corp., Texas, USA). The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to analyze the difference between second- and third-year medical students’ percentages of satisfaction or agreement in each aspect. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. The reliability of the questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha.

III. RESULTS

In years 2 and 3, Cronbach’s alpha of the medical students’ questionnaire was 0.869. In total, 369/387 (95.35%) participants appreciated the course structure and agreed to attend the next TBL session. Students rated the TBL class 4.44 ± 0.627 on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 being severely dissatisfied and 5 very pleased. Students also liked the classroom (4.48 ± 0.738), TBL structure (4.41 ± 0.771), and self-preparation (4.28 ± 0.780). The orientation programme, instructional material, pre-recorded video, and handouts were also well-received. Most students (69.25%, 268/387) spent 1–2 days self-preparing before the TBL class, followed by 3–4 days (24.55%, 95/387) and 5–7 days (5.43%, 21/387), while 0.78% (3/387) did not self-prepare.

On a five-point Likert scale from 1 to 5, students assessed their self-understanding progress, stating that TBL increased their communication, learning, and enthusiasm (4.50 ± 0.796, 4.41 ± 0.781, 4.46 ± 0.795).

The student t-tests revealed no significant differences between students in years 2 and 3. Except time for preparation (Pearson’s Chi-square test; p < 0.005), medical students in years 2 and 3 had similar self-assessment survey scores. In addition, Year 3 medical students also scored better in enthusiasm for studying than Year 2 medical students in increasing self-understanding (Student t-test; p = 0.023) (Table 1).

|

|

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

p-value |

|

Student satisfaction towards the TBL class |

|||

|

Agree to attend the next TBL class: % (n) |

95.95% (213/222) |

94.55% (156/165) |

0.519 |

|

Classroom: mean (SD) |

4.49 (0.671) |

4.47 (0.823) |

0.903 |

|

TBL structure: mean (SD) |

4.38 (0.73) |

4.45 (0.822) |

0.377 |

|

Orientation programme: mean (SD) |

4.46 (0.628) |

4.40 (0.810) |

0.417 |

|

Teaching material: mean (SD) |

4.67 (0.568) |

4.56 (0.578) |

0.064 |

|

Student preparation time: mean (SD) |

4.20 (0.788) |

4.40 (0.755) |

0.012 |

|

Time for preparation: % (n) 1–2 days 3–4 days 5–7 days No preparation |

80.18% (178/222) 14.41% (32/222) 4.50% (10/222) 0.90% (2/222) |

54.55% (90/165) 38.18% (63/165) 6.67% (11/165) 0.61% (1/165) |

< 0.005 |

|

Promotion of learning skills |

|||

|

Communication skills: mean (SD) |

4.46 (0.734) |

4.56 (0.674) |

0.154 |

|

Understanding of the topics: mean (SD) |

4.36 (0.729) |

4.47 (0.845) |

0.180 |

|

Enthusiasm for learning: mean (SD) |

4.38 (0.797) |

4.56 (0.783) |

0.023 |

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

0.869 |

0.869 |

|

Table 1. Comparison between the satisfaction of medical students in years 2 and 3 towards the TBL class and agreement to the promotion of self-understanding

IV. DISCUSSION

TBL changes how students learn by encouraging them to become more accountable by preparing for the team assurance test and application exercise (Burgess et al., 2020a). Teacher-directed pre-class preparation for advanced tasks may involve reading textbooks, reference articles, or instructor-created material while the readiness assurance test enhances students’ enthusiasm for TBL (Parmelee et al., 2012). However, students may resist TBL or active learning because it varies from passive lecture-based learning. Teachers must be aware of this and advocate TBL-style learning to improve ability and encourage students to be more prepared. This research examines the attitudes of medical students towards the two courses post-TBL and provides valuable input on TBL strategies, regardless of the course schedule.

Student feedback can improve teaching and student satisfaction. Students agreed that TBL can improve communication, learning, and passion. Second-year medical students were less motivated than third-year (p = 0.023), implying they need to focus on the core content of the preclinical module rather than TBL preparation, while third years have more time management experience for pre-class self-study. Students liked the teaching material because, in addition to textbooks, the instructors prepared PowerPoint presentations, recorded VDOs, and documentation, allowing those with different learning styles to make the appropriate choice.

Interestingly, both classes found the TBL structure and location less satisfying, possibly because first-time students could not comprehend group activities. Students can further grasp the TBL framework and enjoy the structured process with a revamped instructional layout and additional classes. As for the classroom, the seat layout may prevent suitable group conversations, with a small-group or smart classroom being more appropriate for TBL.

The preparation time satisfaction results are significantly difference, with Year 2 students being considerably less satisfied than Year 3 (p = 0.012). Most second-year medical students spent one to two days planning, and third years one to four (p = 0.005), primarily because the third-year course was longer. Second-year medical students attended a two-week course on human skin and the connective tissue system with a TBL class in the second week, whereas third years took a five-week haematological system course with a TBL class in the fourth week. Both classes received course material on Mondays, while the TBL was on Fridays in the same week. Second-year medical students may need to study the basic science aspects and be unable to independently assess the pre-class material, whereas third-year students had more time. Accordingly, a TBL course should last at least three to four weeks to allow medical students to understand the basic TBL instructional material and independently assess it.

This study has limitations. The questionnaire was expert-evaluated without instructor facilitation. In addition, our study focused on students’ satisfaction with TBL, hence we didn’t include academic outcomes to prove the value of TBL.

V. CONCLUSION

The survey showed that students appreciated TBL-based learning since it helped them to work together and embrace learning, while potentially improving their study skills. A diversity of pre-class material allows students to choose learning tactics depending on their individual abilities. Students found the activity venue inadequate and classroom improvements would boost their satisfaction level.

Notes on Contributors

KW reviewed the literature, designed the study, analysed data, co-wrote the manuscript, critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, and then read it through prior to final approval.

WD reviewed the literature, analysed the data, co-wrote the manuscript, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

WR gave critical feedback on the writing of the manuscript.

AS and KL provided scientific insight and advice, and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

This research was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Chiang Mai University (Study code: PAT-2565-09243).

Data Availability

On reasonable request, the corresponding author will provide data to support the conclusions of this study. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, the data cannot be made public.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to express their sincere appreciation to Ms. Naorn Sriwangdang for assisting with the preparation of the research proposal.

Funding

This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, grant no. 062-2566.

Declaration of Interest

The authors confirm they have no potential conflicts of interest.

References

Burgess, A., Bleasel, J., Hickson, J., Guler, C., Kalman, E., & Haq, I. (2020a). Team-based learning replaces problem-based learning at a large medical school. BMC Medical Education, 20, Article 492. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02362-4

Burgess, A., van Diggele, C., Roberts, C., & Mellis, C. (2020b). Team-based learning: Design, facilitation and participation. BMC Medical Education, 20(Suppl 2), Article 461. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02287-y

Burgess, A. W., McGregor, D. M., & Mellis, C. M. (2014). Applying established guidelines to team-based learning programs in medical schools: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 89(4), 678–688. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000162

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(116), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.330

Parmelee, D., Michaelsen, L. K., Cook, S., & Hudes, P. D. (2012). Team-based learning: A practical guide: AMEE Guide No. 65. Medical Teacher, 34(5), e275–e287. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.651179

*Komson Wannasai

Department of Pathology,

Faculty of Medicine,

Chiang Mai University,

110 Inthavaroros road, Sriphume

Meaung, Chiang Mai, 50200

+6653935442

Email: komson.wanna@gmail.com

Submitted: 11 September 2021

Accepted: 22 March 2023

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 58-61

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/SC2694

Maria Isabel Atienza & Noel Atienza

San Beda University College of Medicine, Philippines

Abstract

Introduction: An evaluation of the online medical course was conducted to assess student readiness, engagement, and satisfaction at the San Beda University College of Medicine in Manila during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology: A convergent mixed methods approach was done with a quantitative online survey and a qualitative thematic analysis of focus group discussions (FGD) with medical students. A total of 440 students participated in the survey while 20 students participated in the FGDs.

Results: The medical students were sufficiently equipped with computers and internet connections that allowed them to access the online medical course from their homes. The 5 themes identified during the study that were relevant to education were: Student readiness for online learning, Learning Management System (LMS) and internet connectivity, teaching and learning activities, the value of engagements, and teaching effectiveness of the faculty. The combined quantitative and qualitative analysis revealed vital issues that affect student learning. This included the need for students to interact with fellow students and to be engaged with their faculty. The issues that affect teaching included the need for continuing faculty training and management skills in delivering the full online course.

Conclusion: The success of online education rests heavily on the interactions of the students, the teachers, and the knowledge. Student interactions, managerial and skills training for the faculty, and providing students with a mix of synchronous and asynchronous activities are the most effective means to ensure the effective delivery of online medical courses.

Keywords: Medical Curricular Revision, Formative Evaluation, Student Engagement, Synchronous and Asynchronous Online Learning, Cognitive Overload

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a shift to online teaching and a revision of the medical curriculum with synchronous and asynchronous online activities. Medical schools worldwide adapted teaching strategies utilising Video Conferencing and Learning Management Systems.

This program evaluation of the online medical course aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of instruction using the various components of online learning. The study centered on the perspectives of students using a mixed methods design (Fitzpatrick et al., 2011). The study focused on the interplay of digital capabilities, students’ perceptions and satisfaction with the interactions and engagements during the online course.

II. METHODS

The mixed methods research protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board of San Beda University. The study utilised a convergent mixed method design with a quantitative online survey that was conducted on 440 respondent students representing each of the four-year levels of the medical school. Six focus group discussion (FGD) sessions were conducted on 20 students. All student participants provided a signed informed consent form to participate in the survey and in the FGDs. The 25-item online survey questionnaire included a 5-point Likert scale for items on readiness for the online course, overall satisfaction, and engagement. The online FGD sessions were conducted using an open-ended questionnaire guide on student capabilities for the online course, student satisfaction, and student engagement.

The FGD recordings were transcribed and subjected to thematic analysis to identify major themes. Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed simultaneously through a joint display of the two sets of results. A joint display using pillar integration was done to demonstrate the themes where the data corroborated or validated each other. The conceptual framework, data collection tools, the data results, and the pillar integration table are posted in a data repository file for this study can be accessed through a repository at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16682569.v2 (Atienza & Atienza, 2021).

III. RESULTS

The survey revealed that students were adequately equipped with the necessary computers and smartphones needed to access the online course. Only 50% of the students were taking the online course from their homes within the same city as the medical school. While 72% encountered internet connectivity problems, 88% of students were successful in the use of the LMS and the videoconferencing platform to access the course and take online examinations.

Seventy-eight percent of students found online student-to-student and faculty-to-class interactions to be beneficial to student learning. Among the synchronous activities, 63% of students preferred live online lectures. Among the asynchronous activities, 52% of students preferred uploaded video lectures. Overall, around 52% of students experienced being overloaded with study requirements while 48% of students felt there was sufficient time for independent study.

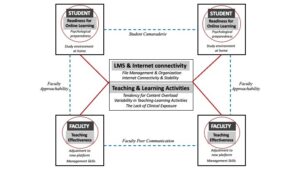

The results of the survey and the thematic analysis of the FGDs were organised into themes and subthemes. These themes were generated from the integration of the quantitative and qualitative data. The schematic diagram (Figure 1) demonstrates how the themes are related to the effectiveness of learning based on the perspective of the students.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of themes and subthemes identified in a mixed methods analysis of a fully online medical course at SBU-COM during the COVID pandemic

A. Student Readiness

The first theme that surfaced from the results was Student Readiness to engage in online learning. Students found their readiness to be dependent on two subthemes:

1) Study environment at home: Students expressed that the sudden shift to studying from home required that they designate sufficient time and space for studying. Students recognised that responsibilities at home and to the family could be distractions if not managed properly.

2) Psychological preparedness: The students also expressed the value of psychological preparedness as essential in dealing with stress and fatigue resulting from the unexpected shift to the online learning mode.

B. LMS and Internet Connectivity

The second theme highlights the importance of having computers and a stable internet connection as major determinants of student satisfaction with the online course. The introduction of an LMS for the medical course required immediate training for both the students and the faculty. While 81% of the students had the necessary gadgets and a good internet signal, 17% experienced major connection problems that disrupted up to 50% of live lectures and offline recorded videos. Student satisfaction with online learning was dependent on how timely and how organised the learning materials were uploaded into the LMS.

C. Teaching and Learning Activities

The third theme refers to the blend of online and offline activities for the different courses. The major subthemes included cognitive overload, variability of teaching and learning activities across courses, and the lack of clinical exposure.

1) Cognitive overload: Students had a perception of being overloaded by the volume of information delivered through the online course. The introduction of new forms of assessments such as video assignments, group reports, and research outputs contributed to the perceived cognitive overload.

2) Variability of teaching and learning activities: The variability in the blend of online and offline activities across the different courses required varying degrees of adjustments from the students. The students expressed their preference for live or recorded lectures over small group discussions and live laboratory demonstrations.

3) Lack of clinical exposure: Students in the 3rd and 4th year levels were apprehensive about the lack of clinical exposure in the actual medical environment due to the restrictions brought about by the pandemic. They recognise that they may not have the necessary skills training needed for internship.

D. The Value of Engagements

Unexpectedly, the fourth theme that students found important in the shift to online learning was the value of engagements.

1) Student-to-student online interactions: Up to 78% of students found support through interactions with other students. These interactions were useful not only for sharing the academic workload but also for mental and emotional support highlighting the value of student camaraderie despite being limited to virtual interactions.

2) Faculty-to-class interactions: Up to 80% of students expressed appreciation for the efforts of the faculty to get student feedback, answer clarificatory questions, and provide explanations when necessary. The students also expressed greater satisfaction with courses delivered online. Both faculty interactions with the class and with individual students were recognised as faculty approachability.

E. Teaching Effectiveness of The Faculty

The fifth theme Teaching pertains to the ability of the faculty to manage the online platform for teaching.

1) Faculty management skills: Teaching effectiveness is facilitated by the ease by which the faculty manages virtual teaching.

2) Faculty peer communication: Students recommend that the faculty within and across different courses coordinate their activities so that students can more easily manage their time and learning.

IV. DISCUSSION

The experience of delivering the medical course online has been very limited in the past. The teaching and learning strategies for medical courses to be delivered fully online require extensive preparation of the three main points in the transaction of learning: the learners, the teachers, and the course content. Learner readiness entails a clear delineation of the study environment in terms of time and space for study. Proper orientation to the online learning environment and psychological support should be made available to the students before the course begins. An inventory of the students’ computers and internet connectivity should also be done to ensure readiness for the course.

Delivering the course online necessitates faculty training on teaching and learning strategies for synchronous and asynchronous delivery as well as the proper navigation of the LMS and its available features. The faculty must maximise the benefits of technology as well as pedagogy in the online learning environment.

This study showed that in the shift of medical education to an online mode during the pandemic, student learning relies heavily on interactions between the learners, the teachers, and the course content. In an online course that relies so much on technology as a means of course delivery and integration, teaching and learning success depends on how well the interactions are established among these three points (Ifinedo & Rikala, 2019).

The design of courses must facilitate student-to-student interactions while faculty-to-class interactions using both synchronous and asynchronous activities would provide a good learning experience for students (Rhim & Han, 2020; Seymour-Walsh et al., 2020).

V. CONCLUSION

To succeed in the delivery of the online medical course, sufficient time must be given for faculty-to-student interactions during synchronous sessions and after the online classes. The faculty must demonstrate approachability by being open to continuing interactions with students outside the synchronous sessions. The coordination of faculty members within and across different courses must be enhanced to reflect efficiency in delivering their respective courses.

This study was performed during the early phase after the shift to full online delivery of the medical course. While the study is based on the perceptions of the students, the results of this study may be valuable in planning for continuing the online delivery of the medical course. The results of this study may be more robust with the inclusion of faculty perceptions and indicators of student academic performance.

Notes on Contributors

Dr. Maria Isabel Atienza conceptualised, designed, and implemented this study. She conducted the focus group discussions, prepared the thematic analysis, and wrote the manuscript for this study.

Dr. Noel Atienza helped in the design and conduct of the online survey and was involved in the data processing and data analysis of the survey. He was also involved in the preparation and editing of the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The research protocol SBU-REB # 2020-028 for this study was reviewed and approved by the San Beda University Research Ethics Board on November 28, 2020.

Data Availability

Data collection tools and research data are available and can be accessed by any interested reader through a repository at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16682569.v2. The data in the repository may not be copied or cited without written permission from the authors.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Alumni of San Beda and their commitment to promoting faculty research activities.

Funding

This study was funded by the Jesus P. Francisco Distinguished Professorial Chair Research Grant from the San Beda College Alumni Foundation, Inc.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

Atienza, M., & Atienza, N. (2021). An online medical course during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods analysis. [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16682569.v2

Fitzpatrick, J., Sanders, J., & Worthen, B. (2011). Program evaluation: Alternative approaches and practical guidelines 4th Edition. Pearson Education, Inc.

Ifinedo, E., & Rikala, J. (2019). TPACK and educational interactions: Pillars of successful technology integration. World Conference on E-Learning. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education, 295-305. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/211094/

Rhim, H., & Han, H. (2020). Teaching online: Foundational concepts of online learning and practical guidelines. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 32(3), 175-183. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2020.171

Seymour-Walsh, A., Bell, A., Weber, A., & Smith, T. (2020). Adapting to a new reality: COVID-19 coronavirus and online education in the health professions. Rural and Remote Health, 20, 6000. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH6000

*Maria Isabel Maniego Atienza

San Beda University, Mendiola Street,

Barangay San Miguel,

City of Manila, Philippines

+639178668751

Email: mimatienza@yahoo.com

Submitted: 15 August 2022

Accepted: 20 December 2022

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 54-57

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/SC2867

Seow Chong Lee & Foong May Yeong

Department of Biochemistry, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: In the first weeks of medical school, students learn fundamental cell biology in a series of lectures taught by five lecturers, followed by a mass tutorial session. In this exploratory study, we examined students’ perceptions of the mass tutorial session over two academic years to find out if they viewed the tutorials differently after minor tweaks were introduced.

Methods: Reflective questions were posted to the undergraduate Year 1 Medical students at the end of each mass tutorial session in 2019 and 2020. Content analysis was conducted on students’ anonymous responses, using each response as the unit of analysis. The responses were categorised under the learning objectives, with responses coded under multiple categories where appropriate. The distribution of the counts from responses in 2019 and 2020 was compared, and the tutorial slides used over the two years were reviewed in conjunction with students’ perceptions to identify changes.

Results: In 2019, we collected 122 responses which coded into 127 unique counts, while in 2020, 119 responses coded into 143 unique counts. Compared to 2019, we noted increases in the percentage of counts under “Link concepts” and “Apply knowledge”, with concomitant decreases in percentage of counts in “Recall contents”. We also found that the 2020 tutorial contained additional slides, including a summary slide and lecture slides in their explanations of answers to the tutorial questions.

Conclusion: Minor tweaks in the tutorial presentation could improve students’ perceptions of our mass tutorials.

Keywords: Mass Tutorials, Students’ Reflections, Apply Knowledge, Link Concepts, Minor Tweaks

I. INTRODUCTION

In the first few weeks of medical school, students learn about cell biology which is fundamental to what they need to know about tissues, organs, and the whole body in a series of lectures co-taught by five lecturers. In the lectures, efforts are made to highlight basic cellular processes, and illustrate how these are inter-connected in a cell. Where appropriate, how knowledge in the biomedical sciences underpins applications in clinical settings is also illustrated by the lecturers. At the end of the series of lectures, the lecturers will co-facilitate a mass tutorial session aimed at summing up the topics.

The mass tutorial session has several learning objectives. These include basic levels of learning such as recalling concepts, preparing for assessments, and building knowledge on topics, to higher levels of learning such as applying concepts to solve real life problems, and linking concepts between topics. Being the only teaching and learning activity that all lecturers co-teach, the mass tutorial provides the best opportunity to demonstrate links and apply the consolidated knowledge learnt during the different lectures.

Once the teaching and learning activities are completed, the coordinator of the lectures Foong May Yeong (YFM) reviews the curriculum to ensure that the teaching and learning activities delivered the intended learning objectives. Such reviews include students’ experiences of the curriculum (Erickson et al., 2008), which the coordinator (YFM) routinely collect through posting reflective questions at the end of the tutorial. In this exploratory study, we analysed students’ reflections from 2019 and 2020, and categorised them under different learning objectives of the tutorial. We noted an increase in percentage counts under “Apply knowledge” and “Link concepts” in 2020 compared to 2019. A review of the tutorial slides revealed the addition of summary and lecture slides in 2020. Our results suggest that minor tweaks to the tutorial presentation are sufficient to help students see the intended usefulness and relevance of tutorials.

II. METHODS

A. Format of Mass Tutorials

The mass tutorial was conducted after completion of the cell lectures. For 2019, this was a face-to-face session. For 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the tutorial was conducted online via Microsoft Teams. The class size was 281 for 2019, and 280 for 2020. Four out of five lecturers taught the same topics for both years. For both years, during the mass tutorial, each lecturer used Poll Everywhere to pose a mix of five to six recall and application questions linked to their topic. Identical questions were used in 2019 and 2020. Students discussed among themselves before answering these questions. The class responses were then revealed, after which the lecturer explained the solutions to their questions. The cycle was repeated until all the lecturers completed their parts.

B. Collection of Student Reflections

After each tutorial, the coordinator (YFM) posted two reflection questions on Poll Everywhere. The two questions were: 1. “What were the key points you learned in this session?”, 2. “Any questions?”. Answering these reflection questions were voluntary and anonymous. A waiver of informed consent was approved by Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine Medical Sciences Departmental Ethics Review Committee. The responses to question 1 obtained from students in 2019 and 2020 were analysed in this study.

C. Content Analysis

The responses to question 1 were coded and categorized into the different learning objectives of the mass tutorial, using each response as a unit of analysis. Each response could be coded into multiple categories when appropriate. The counts under each category were represented as a percentage of all counts coded from the responses. The tutorial slides used in 2019 and 2020 were also reviewed to understand students’ perceptions.

III. RESULTS

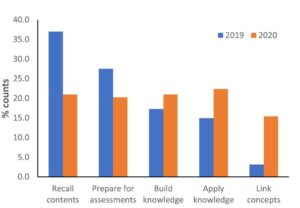

In 2019, we collected 122 responses which were coded into 127 unique counts. In 2020, we collected 119 responses which were coded into 143 unique counts. The number of responses and unique counts coded were largely similar between the two years. The unique counts were categorised into the five learning objectives and their percentage counts were presented in Figure 1. Supplemental data containing an overview of the categories and samples of students’ responses, as well as the counts under each category, are openly available in Tables 1 and 2 shared at Figshare at http://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20484498 (Lee & Yeong, 2022). The distribution of the counts differed between the two years. In 2019, majority of the counts were categorized to “Recall contents” (37.0%), with low numbers categorized as “Apply knowledge” and “Link concepts” (15.0% and 3.1% respectively). In comparison, in 2020, we observed a decrease in percentage of counts in “Recall contents” (to 21.0%), with an increased percentage in counts in “Apply knowledge” and “Link concepts” (to 22.4% and 15.4% respectively). Overall, there is a shift in distribution of counts, from a skewed distribution in 2019, to an even distribution in 2020.

Figure 1. Categorisation of students’ responses into the learning objectives

Given that tutorial questions used in the two years were largely identical, we reviewed the tutorial slides used in these two years to look for possible differences. In 2020, firstly, a summary slide detailing the different aspects of the cell was added to the start of the tutorial slides. Secondly, lecture slides were included in the tutorial slides to explain the answers to the tutorial questions. The lecture slides could come from the lecturer teaching the topic of interest, or from other lecturers if connections across topics were important. These additions could have altered students’ perceptions of the mass tutorial session in 2020.

IV. DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined students’ reflections collected across two academic years to understand their perceptions of the mass tutorial sessions that capped the teaching of cell biology. One of the intentions of the lecturers when designing the tutorial questions was to demonstrate links across topics, and illustrate how questions can be solved using connections across topics. The decrease in percentage of counts under “Recall contents” in 2020 suggested an increase in students’ awareness of the usefulness and relevance of the tutorial sessions when minor changes were made in the presentation of the overview of the cell biology topic and the answers to the tutorial questions.