Simulation instructional design features with differences in clinical outcomes: A narrative review

Submitted: 18 November 2024

Accepted: 14 May 2025

Published online: 7 October, TAPS 2025, 10(4), 5-25

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-4/RA3572

Matthew Jian Wen Low1, Han Ting Jillian Yeo2, Dujeepa D. Samarasekera2, Gene Wai Han Chan1 & Lee Shuh Shing2

1Department of Emergency Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore; 2Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Effective and actionable instructional design features improve return on investment in Technology enhanced simulation (TES). Previous reviews on instructional design features for TES that improve clinical outcomes covered studies up to 2011, but updated, consolidated guidance has been lacking since then. This review aims to provide such updated guidance to inform educators and researchers.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted on instructional design features in TES in medical education. Original research articles published between 2011 to 2022 that examined outcomes at Kirkpatrick level three and above were included.

Results: A total of 30,491 citations were identified. After screening, 31 articles were included in this review. Most instructional design features had a limited evidence base with only one to four studies each, except 11 studies for simulator modality. Improved outcomes were observed with error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training. Mixed results were seen with different simulation modalities, isolated components of mastery learning, just-in-time training, and part versus whole task practice.

Conclusion: There is limited evidence for instructional design features in TES that improve clinical outcomes. Within these limits, error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training appear beneficial. Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness and generalisability of these features.

Keywords: Simulation, Instructional Design, Clinical Outcomes, Review

Practice Highlights

- This review pinpoints additional beneficial instructional design features emerging since 2011.

- These include error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training.

- Further evidence from diverse task and learner contexts is needed to establish generalisability.

- Current evidence continues to suggest no clear superiority of one simulator modality over the other.

I. INTRODUCTION

Technology enhanced simulation (TES) training has been shown to be effective for skills, behaviour, and patient-related outcomes (Cook et al., 2011; McGaghie et al., 2011). Instructional design features in simulation refer to variations in aspects of simulation design that act as active ingredients or mechanisms that make simulation effective, with examples including distributed practice, mastery learning, and range of difficulty (Cook, Hamstra, et al., 2013). Effective instructional design features for TES are actionable for educators because they offer specific, implementable guidance, and an area of research interest (Issenberg et al., 2005; Nestel et al., 2011; Schaefer et al., 2011), including those that lead to transfer to authentic clinical practice (Frerejean et al., 2023; Zendejas et al., 2013).

While it is acknowledged that conducting a study to establish a causal relationship between an educational intervention and subsequent patient and clinical process outcomes is challenging (Cook & West, 2013), such studies become particularly valuable when appropriately executed (Dauphinee, 2012). These studies represent the apex of impact in Kirkpatrick’s model for program evaluation (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006), holding the highest clinical significance and representing the ultimate goal of health professions education which is to enhance patient outcomes by equipping the healthcare workforce to effectively address societal needs (Carraccio et al., 2016). Additionally, the examination of clinical outcomes, when coupled with a consideration of costs, contributes to the informed allocation of limited institutional resources to such educational approaches (Lin et al., 2018).

In prior reviews of TES including studies up to 2011, the vast majority of studies examined outcomes at the levels of reaction and learning demonstrated in written or simulation tests, with only a small body of evidence studying outcomes in workplace contexts (Cook, Hamstra, et al., 2013; Nestel et al., 2011; Zendejas et al., 2013) suggesting that clinical variation, multiple learning strategies, and increased time learning are beneficial variations. This limited evidence base for transfer to workplace contexts hinders educators in fully harnessing the potential of TES to improve patient and system outcomes and obtain the best returns on investments in simulation technology. Given the time interval since these prior reviews, further evidence would have accrued regarding these and other instructional design features.

Given the time elapsed since the last comprehensive review of TES instructional design features, the scarcity of prior studies on clinical outcomes, and the importance of these outcomes, we conducted this narrative review. The objective was to provide an updated understanding of the instructional design features in TES that are associated with enhanced clinical outcomes, thereby addressing a significant gap in the existing literature, to guide educators seeking to optimise instructional design, and provide researchers with an overview of the current state of this literature and guide further inquiry.

II. METHODS

We conducted a narrative review based on the framework proposed by Ferrari (2015). We searched MEDLINE, ERIC, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science databases for articles published from 2012 January 01 to 2022 December 06. We translated abstracts and articles not in English into English using Google Translate.

The following search terms were used: (Medical education) AND (Simulation OR Cadaver OR Simulator OR Augmented Reality OR Virtual reality OR Mixed reality).

Studies were included if they were original research articles examining instructional design variations in TES with at least one outcome at Kirkpatrick levels three or above, as described and utilised by the Best Evidence Medical Education Collaboration (Steinert et al., 2006). We included a broad range of TES modalities, such as computer based virtual reality simulators, high fidelity and static mannequins, plastic models, live animals, inert animal products, and human cadavers as stipulated in the review by Cook et al. (2011). We included augmented reality and mixed reality as they satisfied the prior definition of “materials and devices created or adapted to solve practical problems” in simulation established by Cook et al (2011). Studies where TES was utilised together with human patient actors were included. We included studies with observational, experimental, and qualitative designs.

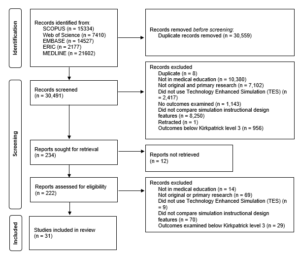

Studies were excluded if they involved only human patient actors as the sole modality of simulation, used simulation outside of health professions education, used simulation for noneducation purposes such as procedural planning or patient education, or only compared simulation with no simulation. We excluded studies involving only nurses given that there are recent and ongoing reviews addressing a similar research question (El Hussein & Cuncannon, 2022; Jackson et al., 2022), but included interprofessional studies. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review and selection process.

Three researchers (MJWL, SSL, JHTY) independently read the full text of articles that met the inclusion criteria and extracted study information including geographical origin, specialty context, type of skill studied, level of the learner, simulation modalities used, instructional design variations studied, and outcomes categorised into the highest Kirkpatrick level studied. Any differences were resolved by a discussion among researchers to arrive at a consensus.

III. RESULTS

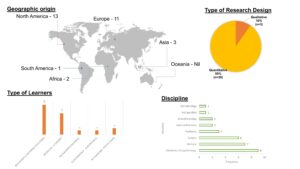

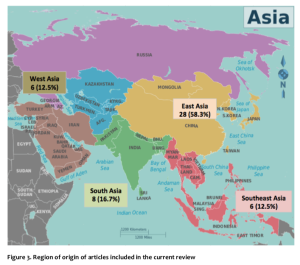

A total of 30,491 records were identified using the search strategy. From these, 31 eligible studies were identified and reviewed (Figure 1 and Table 1). Figure 2 summarises basic information on these studies. The number of studies from each geographic region were 13 from North America (42%), 11 from Europe (35%), three from Asia (10%), two from Africa (6%), and one from South America (3%). One study did not clearly state the countries involved.

28 out of 31 (90%) of the studies adopted a quantitative research design focusing on experimental design. Most simulation interventions were conducted among residents/fellows/interns, followed by medical students.

The results reported in the studies are divided into two groups:

- Evidence suggests improved outcomes

- Evidence shows mixed results

A. Improved Outcomes

Error management training was associated with improved obstetric ultrasound skills compared to error avoidance training in novices (Dyre et al., 2017). Frequent brief on-site simulation, at 40 minutes a month and three minutes a week, was associated with reduced infant mortality compared to a single day course (Mduma et al., 2015). Integrating non-technical skills (NTS) training into a colonoscopy skills curriculum with TES, without increasing time spent teaching, improved observed performance during colonoscopies on real patients, although it was unclear whether this was driven by changes in observed NTS only, or both NTS and technical skills (Walsh et al., 2020).

One qualitative study found that in situ training had greater organisational impact and provided more information for practical organisational changes (Sørensen et al., 2015). One qualitative study found that multi-professional training led to improved communication, leadership, and clinical management of post-partum haemorrhage (Egenberg et al., 2017).

1. Dyad Training

In one study of obstetric ultrasound skills (Tolsgaard et al., 2015) a larger proportion of the dyad training group (71%) scored above the criterion referenced pass fail level than the individual training group (30%) on the objective structured assessment of ultrasound skills, though the difference in mean scores on did not reach statistical significance. Other benefits included increased efficiency from greater faculty to learner ratios.

2. Complex Bundles

Three studies found improvements with complex bundles comprising multiple instructional design variations.

Medical students performed the correct sequence of steps for endotracheal intubation measured by a checklist more often when practice with a mannequin was augmented by a 10-question pre-test, hand held tablets containing scenarios, checklists, and learning algorithms, 24-hour access to the simulation laboratory, and remote review of practice recordings with feedback from teachers via email (Mankute et al., 2022).

Residents had improved observed performance in laparoscopic salpingectomy with lectures, videos, reading materials, a box trainer with pre-set proficiency benchmarks, a VR simulator for technical skills, and non-technical skills training with scripted confederates, compared to a conventional curriculum including simulation with minimal further description (Shore et al., 2016).

In one qualitative study of obstetric residents, there was improved transfer of communication and team work skills and situational awareness with simulation aligned to multiple principles including authenticity, psychological fidelity, engineering fidelity, Paivio’s dual coding, feedback, variability, and increasing complexity (de Melo et al., 2018).

B. Mixed Results

1. Simulation Modality

Eleven studies examined whether outcomes differed when different simulation modalities were used. Examples include higher versus lower technological complexity in a physical simulator (DeStephano et al., 2015; Sharara-Chami et al., 2014), cadaveric versus synthetic models (Lal et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2018; Tchorz et al., 2015), virtual reality (VR) versus physical simulators (Daly et al., 2013; Gomez et al., 2015; Orzech et al., 2012; O’Sullivan et al., 2014), and a computer based versus physical simulated operating room for student orientation (Patel et al., 2012).

Overall, there no clear pattern of superiority of a particular type of simulator. Most studies found no difference, with three exceptions: Gomez et al (2012) found that VR alone, and VR with physical simulator, led to superior performance in observed colonoscopic skills in real patients, compared to physical simulator alone; Chunharas et al (2013) found that adding practice on fellow students on top of mannequin practice improved observed performance in subcutaneous and intramuscular injection skills; Patel et al (2012) found that using a physical simulated operating room was superior to an online computer based operating room for training novice medical students in appropriate behaviour in the operating room.

To view Table 1 click here.

Abbreviations. ACS/APDS: American College of Surgeons / Association of Program Directors in Surgery; EAT: Error avoidance training; EMT: Error management training; GAGES-C: Global Assessment of Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Skills-Colonoscopy; GOALS: Global Operative Assessment of Laparoscopic Skills; ISS: In situ simulation; JAG DOPS: Joint Advisory Group Direct Observation of Procedural Skills; JIT: Just in time; OSA-LS: objective structured assessment of laparoscopic salpingectomy; NTS: Non-technical skills. OSAUS: objective structured assessment of ultrasound; OSS: Off-site simulation; PGY: Post graduate year; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America; VR: Virtual reality.

Kirkpatrick levels. 1: Reaction e.g. participants’ views on learning experience; 2a: Learning – Change in attitudes; 2b: Learning – Modification of knowledge or skills; 3: Behaviour – Change in behaviours; 4a: Results – Change in the system/organisational practice; 4b: Results – Change in patient outcomes.

Table 1. List of included studies and skills, instructional design variations and outcomes examined

Figure 1. Flow of studies through identification process

Figure 2. Summary of geographical origin, type of research, type of learners and disciplines studied

2. Components of Mastery Learning

Four studies examined components of mastery learning, such as progressive task difficulty and proficiency-based progression. Progressive task difficulty for TES was associated with improved rater observed colonoscopic performance on real patients (Grover et al., 2017), while the evidence was mixed for proficiency-based progression for TES, with studies finding reduced epidural failure rates (Srinivasan et al., 2018) and fewer adverse events in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (De Win et al., 2016), while another found no difference in operative performance for bowel anastomosis in real patients (Naples et al., 2022).

3. Part Versus Whole Task

Two studies compared part versus whole task training. Both found no difference, in rater observed performance in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (Hernández-Irizarry et al., 2016), and intraoperative camera navigation skills (Nilsson et al., 2017), though randomised part task training led to faster skills mastery with greater cost effectiveness compared to whole task training.

4. Increased Time Spent in Simulation Training

Two studies examined amount of time spent in simulation training. One study showed reduced incidence of malpractice claims (Schaffer et al., 2021), while another study found no difference in successful deep biliary cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (Liao et al., 2013).

5. Just in Time (JIT) Training

Overall, there was mostly no benefit seen with JIT training with TES, across three studies. One study examined the addition of JIT video after prior TES (Todsen et al., 2013), and one study compared JIT practice alone, JIT practice with feedback from this practice, and feedback alone derived from baseline testing (Kroft et al., 2017). JIT and just-in-place physical simulator training did not improve first pass lumbar puncture success, but improved mean number of attempts and process measures such as early stylet removal (Kessler et al., 2015).

IV. DISCUSSION

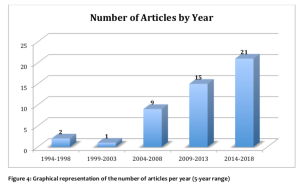

We sought to provide an updated synthesis on effective instructional design features in simulation in medical education, focusing on those that produce higher level outcomes at Kirkpatrick levels three and above. A prior review searching until 2011 identified only 18 studies that examined outcomes at Kirkpatrick level three and above, out of their pool of 10,297 studies. Our review reveals a notable rise in the number of studies over the past ten years, exploring instructional design and clinical outcomes. In the discussion that follows, we synthesise the findings with existing literature and theory to extract valuable insights for medical educators.

A. Implications for Current Practice

This review underscores the necessity of directing resources towards effective instructional design features, emphasising that these need not be strictly tied to specific simulator types, as advocated by Norman. Despite the ongoing evolution and incorporation of an expanding array of TES modalities, including Virtual Reality (VR) in this review, we observed mixed results concerning simulation modality as an instructional design variation. Upon closer examination of interventions outlined in studies comparing simulation modalities, it becomes evident that confounding factors may arise due to variations in the application of training to proficiency criteria (a characteristic of mastery learning) or differences in the quality of measurement.

In the study conducted by Gomez et al (2015), training to proficiency criteria was incorporated in study arms demonstrating benefit (VR and VR plus physical simulator) and not incorporated in the remaining arm (physical simulator alone). Similarly, in the study by Orzech et al (2012) where training until proficiency criteria were reached was a shared feature of both arms, no significant difference between groups was observed. It remains unclear whether observed differences were attributable to the application of training until proficiency criteria were met or to the varied simulation modalities.

Chunharas et al (2013) and Patel et al (2012) also noted outcome differences when comparing different simulation modalities. However, the robustness of these findings is constrained using a checklist observation scale developed for individual studies with minimal validity evidence. Clinical and task variations, recognised as beneficial in prior reviews (Zendejas et al., 2013), may elucidate the advantages identified by Chunharas et al and the VR plus physical simulator arm in the study by Gomez et al.

Components of mastery learning appear mostly effective, although isolated implementation of a component without the whole may erode effectiveness. The inconsistent evidence for effectiveness of components of mastery learning in this review is surprising, given prior evidence for the effectiveness of mastery learning for translational outcomes (Griswold-Theodorson et al., 2015). The difference may lie in piecemeal rather than holistic implementation of mastery learning as a complex intervention, with seven complementary components working together (McGaghie, 2015).

Another difference is that our review only included studies comparing different TES interventions, while the review by Griswold-Theodorson et al included studies that compared mastery learning with a wider range of comparators, including no TES. Notably, a separate systematic review and meta-analysis of mastery learning found only three studies from 1984-2010 comparing mastery learning to other TES interventions for patient outcomes, with no statistically significant benefit overall and substantial heterogeneity (Cook, Brydges, et al., 2013).

Methodological issues may be another contributory factor. Naples et al (2022) postulate in their study the reasons for the lack of observed difference, including a long duration between intervention and outcome assessment, which was longer in the intervention group than the control group, biasing towards the null, and surprisingly high baseline performance with an insufficiently sensitive rater observation tool. This study had only nine participants, limiting statistical power. These represent important methodological considerations for researchers designing educational intervention studies.

The effectiveness of increased time spent in simulation training is associated with incorporation of learning conversations. Discrepancies in outcomes between the two studies assessing the impact of time spent in simulation training may be attributed to the presence of debriefing in the study conducted by Schaffer et al (2021), as opposed to un-coached practice without feedback in the study by Liao et al (2013). It is crucial to note that the advantages derived from extended training periods are not solely attributed to prolonged duration but are also influenced by the integration of learning conversations. These conversations encompass both debriefing and feedback (Tavares et al., 2020), both of which have demonstrated efficacy, as supported by existing research (Cheng et al., 2014; Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

In a systematic review by Hatala and colleagues (Hatala et al., 2014), feedback emerged as moderately effective for procedural skills simulation training. Notably, feedback from multiple sources, including instructors, proved more effective than feedback from a single source.

Distributed practice is preferred over blocked practice for TES. Frequent brief simulation (Mduma et al., 2015) essentially describes distributed rather than blocked practice. The increased effectiveness seen with distributed practice here is consistent with existing literature within (Cecilio-Fernandes et al., 2023) and outside (Dunlosky et al., 2013) of health professions education.

Dyad training is notable for being efficient with similar or better outcomes, and is consistent with existing literature on motor skills learning (Wulf et al., 2010). The optimal group size has not been clearly determined, beyond single versus dyad, and would be a productive avenue of inquiry for evidence-based determination of learner to faculty ratios, accounting for contextual factors such as task complexity and stage of learner’s development.

In situ simulation may be beneficial in generating participant insights that feed into systems-based improvements through quality improvement mechanisms (Calhoun et al., 2024; Nickson et al., 2021). This combines multiple mechanisms by which TES can produce meaningful impact: through changing individual learner behaviour and changing systems processes.

Error management training appears beneficial for transfer outcomes in novices. This is congruent with literature outside of medical education (Keith & Frese, 2008). The limited evidence base within medical education makes this ripe for further study across task and learner types.

In summary, the features mentioned above are predominantly drawn from previous studies, primarily conducted at Kirkpatrick level two. This review contributes by offering an updated synthesis of evidence, outlining the extent to which this evidence can be extrapolated to higher Kirkpatrick levels, and highlighting features that were previously unexplored at clinical process and outcome levels. Collectively, evidence spanning these levels serves as a guide for those designing TES with the goal of achieving educational and clinical impact.

B. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Studies that examine Kirkpatrick levels three and above continue to constitute a relatively small fraction of the overall research landscape. Furthermore, this limited body of research is dispersed among various instructional design features, with only a small number of studies investigating each specific feature. Consequently, drawing definitive conclusions about effectiveness becomes challenging, representing a primary constraint of this review. Despite these limitations, we have tried to extract valuable insights for health professions educators by synthesising the findings with existing literature and theory.

The limited evidence bases for most individual instructional design features, especially those demonstrating benefits at Kirkpatrick levels three and four, limits the strength of conclusions that can be drawn about their effectiveness. Further studies replicating these results would strengthen the argument that a particular instructional design feature is able to achieve clinical impact. The evidence base is also limited in the variety of task and learner contexts studied for each individual instructional design feature. Determining the generalisability of these findings requires further research applying these features across diverse TES contexts with different skills and learner groups. Future research should also continue to explore novel and promising instructional design features, such as hybrid simulations where mannequins are overlayed with animal tissue or gel-based phantoms (Balakrishnan et al., 2025).

V. CONCLUSION

There is limited evidence for instructional design features in TES that translate to improved clinical outcomes. Within these limits, error management training, distributed practice, dyad training, and in situ training appear beneficial. Given the limited evidence base for these individual features, definitive determination of effectiveness and generalisability requires further research applying promising target features across different task and learner contexts.

Notes on Contributors

Matthew Low is an emergency physician at National University Hospital, Singapore, and adjunct assistant professor at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Jillian Yeo is a medical educationalist at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Dujeepa Samarasekera is senior director at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Gene Chan is an emergency physician at National University Hospital, Singapore, and adjunct assistant professor at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Shuh Shing Lee is a medical educationalist at the Centre for Medical Education, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Matthew Low, Jillian Yeo and Shuh Shing Lee conceived of the work, collected and analysed data, and drafted the work. Gene Chan and Dujeepa Samarasekera conceived of the work and reviewed it critically for important intellectual content. All contributors gave final approval of the version to be published and are agreeable to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not applicable as this is a review paper.

Funding

There was no funding for this paper.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

Balakrishnan, A., Law, L. S.-C., Areti, A., Burckett-St Laurent, D., Zuercher, R. O., Chin, K.-J., & Ramlogan, R. (2025). Educational outcomes of simulation-based training in regional anaesthesia: A scoping review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 134(2), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2024.07.037

Calhoun, A. W., Cook, D. A., Genova, G., Motamedi, S. M. K., Waseem, M., Carey, R., Hanson, A., Chan, J. C. K., Camacho, C., Harwayne-Gidansky, I., Walsh, B., White, M., Geis, G., Monachino, A. M., Maa, T., Posner, G., Li, D. L., & Lin, Y. (2024). Educational and patient care impacts of in situ simulation in healthcare: A systematic review. Simulation in Healthcare, 19(1S), S23–S31. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000773

Carraccio, C., Englander, R., Van Melle, E., Ten Cate, O., Lockyer, J., Chan, M.-K., Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., & International Competency-Based Medical Education Collaborators. (2016). Advancing competency-based medical education: A charter for clinician-educators. Academic Medicine, 91(5), 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001048

Cecilio-Fernandes, D., Patel, R., & Sandars, J. (2023). Using insights from cognitive science for the teaching of clinical skills: AMEE Guide No. 155. Medical Teacher, 45(11), 1214–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2168528

Cheng, A., Eppich, W., Grant, V., Sherbino, J., Zendejas, B., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Debriefing for technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education, 48(7), 657–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12432

Chunharas, A., Hetrakul, P., Boonyobol, R., Udomkitti, T., Tassanapitikul, T., & Wattanasirichaigoon, D. (2013). Medical students themselves as surrogate patients increased satisfaction, confidence, and performance in practicing injection skill. Medical Teacher, 35(4), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.746453

Cook, D. A., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Hamstra, S. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Mastery learning for health professionals using technology-enhanced simulation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Academic Medicine, 88(8), 1178–1186. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a365d

Cook, D. A., Hamstra, S. J., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-based education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Teacher, 35(1), e867-898. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.714886

Cook, D. A., Hatala, R., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hamstra, S. J. (2011). Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 306(9), 978–988. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1234

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2013). Perspective: Reconsidering the focus on “outcomes research” in medical education: A cautionary note. Academic Medicine, 88(2), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827c3d78

Daly, M. K., Gonzalez, E., Siracuse-Lee, D., & Legutko, P. A. (2013). Efficacy of surgical simulator training versus traditional wet-lab training on operating room performance of ophthalmology residents during the capsulorhexis in cataract surgery. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 39(11), 1734–1741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.05.044

Dauphinee, W. D. (2012). Educators must consider patient outcomes when assessing the impact of clinical training. Medical Education, 46(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04144.x

de Melo, B. C. P., Rodrigues Falbo, A., Sorensen, J. L., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & van der Vleuten, C. (2018). Self-perceived long-term transfer of learning after postpartum haemorrhage simulation training. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 141(2), 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12442

De Win, G., Van Bruwaene, S., Kulkarni, J., Van Calster, B., Aggarwal, R., Allen, C., Lissens, A., De Ridder, D., & Miserez, M. (2016). An evidence-based laparoscopic simulation curriculum shortens the clinical learning curve and reduces surgical adverse events. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 7, 357–370. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S102000

DeStephano, C. C., Chou, B., Patel, S., Slattery, R., & Hueppchen, N. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of birth simulation for medical students. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 213(1), 91.e1-91.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.024

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266

Dyre, L., Tabor, A., Ringsted, C., & Tolsgaard, M. G. (2017). Imperfect practice makes perfect: Error management training improves transfer of learning. Medical Education, 51(2), 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13208

Egenberg, S., Karlsen, B., Massay, D., Kimaro, H., & Bru, L. E. (2017). “No patient should die of PPH just for the lack of training!” Experiences from multi-professional simulation training on postpartum haemorrhage in northern Tanzania: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 17(1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0957-5

El Hussein, M. T., & Cuncannon, A. (2022). Nursing students’ transfer of learning from simulated clinical experiences into clinical practice: A scoping review. Nurse Education Today, 116, 105449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105449

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Frerejean, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Condron, C., Strauch, U., & Eppich, W. (2023). Critical design choices in healthcare simulation education: A 4C/ID perspective on design that leads to transfer. Advances in Simulation (London, England), 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-023-00242-7

Gomez, P. P., Willis, R. E., & Van Sickle, K. (2015). Evaluation of two flexible colonoscopy simulators and transfer of skills into clinical practice. Journal of Surgical Education, 72(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.08.010

Griswold-Theodorson, S., Ponnuru, S., Dong, C., Szyld, D., Reed, T., & McGaghie, W. C. (2015). Beyond the simulation laboratory: A realist synthesis review of clinical outcomes of simulation-based mastery learning. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1553–1560. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000938

Grover, S. C., Scaffidi, M. A., Khan, R., Garg, A., Al-Mazroui, A., Alomani, T., Yu, J. J., Plener, I. S., Al-Awamy, M., Yong, E. L., Cino, M., Ravindran, N. C., Zasowski, M., Grantcharov, T. P., & Walsh, C. M. (2017). Progressive learning in endoscopy simulation training improves clinical performance: A blinded randomized trial. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 86(5), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1529

Hatala, R., Cook, D. A., Zendejas, B., Hamstra, S. J., & Brydges, R. (2014). Feedback for simulation-based procedural skills training: A meta-analysis and critical narrative synthesis. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 19(2), 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-013-9462-8

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hernández-Irizarry, R., Zendejas, B., Ali, S. M., & Farley, D. R. (2016). Optimizing training cost-effectiveness of simulation-based laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. American Journal of Surgery, 211(2), 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.027

Issenberg, S. B., McGaghie, W. C., Petrusa, E. R., Lee Gordon, D., & Scalese, R. J. (2005). Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: A BEME systematic review. Medical Teacher, 27(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046924

Jackson, M., McTier, L., Brooks, L. A., & Wynne, R. (2022). The impact of design elements on undergraduate nursing students’ educational outcomes in simulation education: Protocol for a systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 11(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-01926-3

Keith, N., & Frese, M. (2008). Effectiveness of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.59

Kessler, D., Pusic, M., Chang, T. P., Fein, D. M., Grossman, D., Mehta, R., White, M., Jang, J., Whitfill, T., Auerbach, M., & INSPIRE LP investigators. (2015). Impact of just-in-time and just-in-place simulation on intern success with infant lumbar puncture. Pediatrics, 135(5), e1237-1246. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014 -1911

Kirkpatrick, D., & Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kroft, J., Ordon, M., Po, L., Zwingerman, N., Waters, K., Lee, J. Y., & Pittini, R. (2017). Preoperative practice paired with instructor feedback may not improve obstetrics-gynaecology residents’ operative performance. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9(2), 190–194. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00238.1

Lal, B. K., Cambria, R., Moore, W., Mayorga-Carlin, M., Shutze, W., Stout, C. L., Broussard, H., Garrett, H. E., Nelson, W., Titus, J. M., Macdonald, S., Lake, R., & Sorkin, J. D. (2022). Evaluating the optimal training paradigm for transcarotid artery revascularization based on worldwide experience. Journal of Vascular Surgery, 75(2), 581-589.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2021.08.085

Liao, W.-C., Leung, J. W., Wang, H.-P., Chang, W.-H., Chu, C.-H., Lin, J.-T., Wilson, R. E., Lim, B. S., & Leung, F. W. (2013). Coached practice using ERCP mechanical simulator improves trainees’ ERCP performance: A randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy, 45(10), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1344224

Lin, Y., Cheng, A., Hecker, K., Grant, V., & Currie, G. R. (2018). Implementing economic evaluation in simulation-based medical education: Challenges and opportunities. Medical Education, 52(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13411

Mankute, A., Juozapaviciene, L., Stucinskas, J., Dambrauskas, Z., Dobozinskas, P., Sinz, E., Rodgers, D. L., Giedraitis, M., & Vaitkaitis, D. (2022). A novel algorithm-driven hybrid simulation learning method to improve acquisition of endotracheal intubation skills: A randomized controlled study. BMC Anaesthesiology, 22(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01557-6

McGaghie, W. C. (2015). Mastery learning: It is time for medical education to join the 21st century. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1438–1441. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000911

McGaghie, W. C., Issenberg, S. B., Cohen, E. R., Barsuk, J. H., & Wayne, D. B. (2011). Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 86(6), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

Mduma, E., Ersdal, H., Svensen, E., Kidanto, H., Auestad, B., & Perlman, J. (2015). Frequent brief on-site simulation training and reduction in 24-h neonatal mortality—An educational intervention study. Resuscitation, 93, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.04.019

Naples, R., French, J. C., Han, A. Y., Lipman, J. M., & Awad, M. M. (2022). The impact of simulation training on operative performance in general surgery: Lessons learned from a prospective randomized trial. Journal of Surgical Research, 270, 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.10.003

Nestel, D., Groom, J., Eikeland-Husebø, S., & O’Donnell, J. M. (2011). Simulation for learning and teaching procedural skills: The state of the science. Simulation in Healthcare, 6 Suppl, S10-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e318227ce96

Nickson, C. P., Petrosoniak, A., Barwick, S., & Brazil, V. (2021). Translational simulation: From description to action. Advances in Simulation (London, England), 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-021-00160-6

Nilsson, C., Sorensen, J. L., Konge, L., Westen, M., Stadeager, M., Ottesen, B., & Bjerrum, F. (2017). Simulation-based camera navigation training in laparoscopy—A randomized trial. Surgical Endoscopy, 31(5), 2131–2139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-5210-5

Orzech, N., Palter, V. N., Reznick, R. K., Aggarwal, R., & Grantcharov, T. P. (2012). A comparison of 2 ex vivo training curricula for advanced laparoscopic skills: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Surgery, 255(5), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824aca09

O’Sullivan, O., Iohom, G., O’Donnell, B. D., & Shorten, G. D. (2014). The effect of simulation-based training on initial performance of ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus blockade in a clinical setting—A pilot study. BMC Anaesthesiology, 14, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2253-14-110

Patel, V., Aggarwal, R., Osinibi, E., Taylor, D., Arora, S., & Darzi, A. (2012). Operating room introduction for the novice. American Journal of Surgery, 203(2), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.03.003

Schaefer, J. J., Vanderbilt, A. A., Cason, C. L., Bauman, E. B., Glavin, R. J., Lee, F. W., & Navedo, D. D. (2011). Literature review: Instructional design and pedagogy science in healthcare simulation. Simulation in Healthcare, 6 Suppl, S30-41. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e31822237b4

Schaffer, A. C., Babayan, A., Einbinder, J. S., Sato, L., & Gardner, R. (2021). Association of simulation training with rates of medical malpractice claims among obstetrician-gynaecologists. Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 138(2), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004464

Sharara-Chami, R., Taher, S., Kaddoum, R., Tamim, H., & Charafeddine, L. (2014). Simulation training in endotracheal intubation in a paediatric residency. Middle East Journal of Anaesthesiology, 22(5), 477–485.

Shore, E. M., Grantcharov, T. P., Husslein, H., Shirreff, L., Dedy, N. J., McDermott, C. D., & Lefebvre, G. G. (2016). Validating a standardized laparoscopy curriculum for gynaecology residents: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 215(2), 204.e1-204.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.037

Sørensen, J. L., Navne, L. E., Martin, H. M., Ottesen, B., Albrecthsen, C. K., Pedersen, B. W., Kjærgaard, H., & van der Vleuten, C. (2015). Clarifying the learning experiences of healthcare professionals with in situ and off-site simulation-based medical education: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 5(10), e008345. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008345

Srinivasan, K. K., Gallagher, A., O’Brien, N., Sudir, V., Barrett, N., O’Connor, R., Holt, F., Lee, P., O’Donnell, B., & Shorten, G. (2018). Proficiency-based progression training: An “end to end” model for decreasing error applied to achievement of effective epidural analgesia during labour: A randomised control study. BMJ Open, 8(10), e020099. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020099

Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Centeno, A., Dolmans, D., Spencer, J., Gelula, M., & Prideaux, D. (2006). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Medical Teacher, 28(6), 497–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600902976

Tan, T. X., Buchanan, P., & Quattromani, E. (2018). Teaching residents chest tubes: Simulation task trainer or cadaver model? Emergency Medicine International, 2018, 9179042. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9179042

Tavares, W., Eppich, W., Cheng, A., Miller, S., Teunissen, P. W., Watling, C. J., & Sargeant, J. (2020). Learning conversations: An analysis of the theoretical roots and their manifestations of feedback and debriefing in medical education. Academic Medicine, 95(7), 1020–1025. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002932

Tchorz, J. P., Brandl, M., Ganter, P. A., Karygianni, L., Polydorou, O., Vach, K., Hellwig, E., & Altenburger, M. J. (2015). Pre-clinical endodontic training with artificial instead of extracted human teeth: Does the type of exercise have an influence on clinical endodontic outcomes? International Endodontic Journal, 48(9), 888–893. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12385

Todsen, T., Henriksen, M. V., Kromann, C. B., Konge, L., Eldrup, J., & Ringsted, C. (2013). Short- and long-term transfer of urethral catheterization skills from simulation training to performance on patients. BMC Medical Education, 13, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-29

Tolsgaard, M. G., Madsen, M. E., Ringsted, C., Oxlund, B. S., Oldenburg, A., Sorensen, J. L., Ottesen, B., & Tabor, A. (2015). The effect of dyad versus individual simulation-based ultrasound training on skills transfer. Medical Education, 49(3), 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12624

Walsh, C. M., Scaffidi, M. A., Khan, R., Arora, A., Gimpaya, N., Lin, P., Satchwell, J., Al-Mazroui, A., Zarghom, O., Sharma, S., Kamani, A., Genis, S., Kalaichandran, R., & Grover, S. C. (2020). Non-technical skills curriculum incorporating simulation-based training improves performance in colonoscopy among novice endoscopists: Randomized controlled trial. Digestive Endoscopy, 32(6), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.13623

Wulf, G., Shea, C., & Lewthwaite, R. (2010). Motor skill learning and performance: A review of influential factors. Medical Education, 44(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03421.x

Zendejas, B., Brydges, R., Wang, A. T., & Cook, D. A. (2013). Patient outcomes in simulation-based medical education: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(8), 1078–1089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2264-5

*Matthew Low

Emergency Medicine Department,

National University Hospital

9 Lower Kent Ridge Road, Level 4,

Singapore 119085

Email: mlow@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 7 April 2024

Accepted: 5 February 2025

Published online: 1 April, TAPS 2025, 10(2), 34-45

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2025-10-2/RA3272

Jasmin Oezcan1, Marcus A. Henning2 & Craig S. Webster2

1Pediatric Department, Erlangen University Hospital, Erlangen, Germany; 2Centre for Medical and Health Sciences Education, School of Medicine, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Abstract

Introduction: Paediatric practice presents unique challenges for clinical reasoning, including the collection of clinical information from multiple individuals during history taking, often in emotionally charged circumstances, and the variable presentation of signs and symptoms due to the developmental stage of the child. Communication skills are clearly important but the most effective methods of teaching clinical reasoning in paediatrics remains unclear. Our review aimed to examine the existing methods of teaching clinical reasoning in paediatrics, and to consider the evidence for the most effective approaches.

Methods: We performed a scoping review and evidence synthesis drawn from reports found during a systematic search in five major databases. We reviewed 211 reports to include 11.

Results: Students who received explicit training in clinical reasoning showed a significant improvement in their experiential learning, diagnostic ability, and reflective clinical judgement. More specifically, key findings demonstrated frequent student-centered interactive strategies increased awareness of the critical role of communication skills and medical history taking. Real case-based exercises, flipped classrooms, workshops, team-based or/and bed-side teaching, and clinical simulation involving multisource feedback were effective in improving student engagement and performance on multiple outcome measures.

Conclusion: This review provides a structured insight into the advantages of different teaching methods, focusing on the multistep decision process involved in teaching clinical reasoning in paediatrics. Our review demonstrated a relatively small number of studies in paediatrics related to clinical reasoning, underlining the need for further research and curricular developments that may better meet the known unique challenges of the care of paediatric patients.

Keywords: Clinical Reasoning, Paediatrics, Teaching Methods, Medical Students

Practice Highlights

- Clinical reasoning in paediatrics involves unique challenges including the collection of clinical information from multiple people (child, parents and care givers), symptoms that may present differently due to children’s stage of development, and complex pharmacokinetics.

- The efficacy of paediatric training could be increased by combining student-centered methods like flipped-classroom, team-based or bed-side teaching and simulation.

- Low stakes training such as simulation that allows repetition and learning from mistakes is particularly effective and engaging for students.

- Our review demonstrated a relatively small number of studies specifically related to clinical reasoning in paediatrics, underlining the need for further research and curricular developments that may better meet the known unique challenges of the care of paediatric patients.

I. INTRODUCTION

Reflective diagnostic skills, comprising the analyses of symptoms and health issues and the weighing up of alternative explanations, are essential for establishing a correct diagnosis and for successful treatment and patient management. In addition, it is important to acknowledge that conscious and unconscious biases may be associated with human errors underlining clinical decision-making (Croskerry, 2005; Webster, Taylor, et al., 2021). The prevalence of incorrect acute clinical diagnosis has been estimated at 5-15% and emphasises the importance of understanding and minimising reasoning errors (Scott, 2009). It has been estimated that 75% of diagnostic errors may be associated with problems of clinical reasoning, in particular related to failures to elicit, synthesise, decide, or act on clinical information (Graber et al., 2005; Pennaforte et al., 2016).

Clinical reasoning requires a competent and highly developed cognitive process, which can use experiential and formal knowledge to work through a cluster of symptoms to generate a correct diagnosis (Pinnock & Welch, 2014). A general approach should incorporate comprehensive problem-solving and involves the need for clear questioning to discern a set of viable differential diagnoses while remaining mindful of the potential of bias in the decision-making process (Pinnock et al., 2021).

The practice of paediatric medicine, however, presents particular challenges for a careful, question-based process of differential diagnosis. Taking a medical history typically requires the collection of clinical information from multiple individuals, including parents, caregivers and the child themselves, often in emotionally charged circumstances. In addition, symptoms in children and neonates can be subtle and unclear – children often have limited communication abilities, their symptoms may present differently depending on their stage of development, many diagnostic tools and tests are designed for adults and have limited utility in children, and children may have unexpected sensitivities and responses to medications due to having pharmacokinetics that are very different to those of adults (Webster, Anderson, et al., 2021).

Despite these challenges, the teaching and experience of clinical reasoning for trainees in paediatrics is often informal and occurs in an unstructured way throughout clinical attachments. In addition, there is often a lack of opportunity to review performance with an experienced clinician, which hinders the development of insight regarding common causes of errors (Lee et al., 2010; Schmidt & Mamede, 2015). It is well known that quality supervision and feedback leads to better learning in trainees, however, there is often a shortage of appropriately qualified paediatricians able to provide such supervision and feedback (de Jong & Ferguson-Hessler, 1996; Zhang et al., 2019).

The medical curriculum typically focuses on the acquisition of content knowledge, cultivating both theory and practical skills, which culminates in the ability to develop a treatment strategy for the patient (Norman, 2005). Clinical reasoning can be described as a multistep process consisting of: data gathering; the proposal of a diagnosis from a range of possible different hypotheses, and the reevaluation of that proposal in light of new information.

Early approaches to the teaching of diagnostic reasoning included the hypothetico-deductive procedural method that involved establishing a series of hypotheses, which then required the gathering of selective patient data to confirm or rule out the hypotheses being made (Norman, 2005; Schwartz & Elstein, 2008). This approach was intended to promote an understanding of the physical development of a disease or condition, and is also known as the pathophysiological approach, and relies on hypothetico-deductive reasoning and knowledge acquisition (Page et al., 1995). Hence, this approach may not represent the most efficient way to cultivate clinically relevant skills. An alternative approach involves the explanation of an expert’s reasoning as an unconscious and automatic pattern recognition process (Groen & Patel, 1985; Schwartz & Elstein, 2008). This can be linked with the dual-cognition theory (Marcum, 2012). It has been suggested that in 95% of case encounters, expert clinicians use the fast, automatic, and unconscious pattern recognition abilities of system 1, while system 2, which is conscious, slow and effortful, tends to be applied only in unusual and complicated cases (Fabry, 2022; Webster, Taylor, et al., 2021). Studies have underlined that both systems should be used simultaneously to ensure an efficient outcome (Pennaforte et al., 2016). Therefore, the teaching of the awareness of individual unconscious information processing and judgment is a major pedagogical challenge, particularly in potentially difficult practice domains such as paediatrics (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Gruppen & Frohna, 2002; Webster et al., 2022).

It takes years to train a qualified paediatrician with accurate perception and judgment, enabling them to work effectively with children and their parents, guardians, or caregivers (Gong et al., 2022). Gathering the medical history appropriately and forming an accurate diagnosis through a reliable clinical reasoning process is a critical professional competency in paediatricians, which may require specific curricular techniques to achieve. Therefore in this review we aimed to examine the existing methods of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnosis in paediatrics, and to consider the evidence for which approaches may be the most effective.

II. METHODS

A. The Search Process

In consideration of the array and typology of available reviews, we choose the scoping review because it is a useful synthesis approach to create an overview of the salient literature and to identify key findings. A preliminary search identified no published review with an equal or comparable research question as the current work, suggesting that our scoping review may allow priorities for future investigations to be outlined, including potentially informing later systematic reviews (Grant & Booth, 2009). The literature search was conducted during the period of March and April 2023, using five major databases (Pubmed, PsychInfo, Scopus, ERIC, and Google Scholar). We aimed to identify studies, without restriction of type or year of publication, reported in English or German, to capture as much of the Western thought on clinical reasoning in paediatrics as possible and to make the most of the language fluency of the authors. The search employed the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) framework and the terms listed in Table 1 (Schardt et al., 2007). These search terms were used according to the following structure, for example: “medical-student” AND “clinical-reasoning” AND “paediatrics”. The search included MeSH terms, truncations, subject headings, word variants and incorporated both American and British spellings.

|

Types of participants |

Types of intervention |

Types of comparison |

Types of outcomes |

|

Medical-students, clinic*ians, experts and teachers. |

Clinical-reasoning, paediatric setting, clinical-rotation, medicine |

Types of educational system, study types and teaching methods.

|

Depending on the study type the comparison of assessment and efficacy. |

Table 1. PICO Framework Components

B. Data Analysis

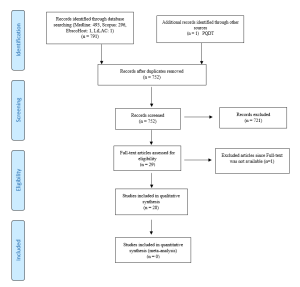

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was utilised as an evidence-based guideline for the inclusion and exclusion process, as illustrated in the flow diagram (Figure 1) (Moher et al., 2009). Author JO screened reports initially by title and abstract, with uncertainties being resolved at regular meetings with authors MAH and CSW. Those with suitable titles were placed in a citation management program (Vanhecke, 2008). We included studies that focused on teaching methods in clinical reasoning in paediatrics, in particular approaches that were intended to improve the quality of reasoning and decision making (see Figure 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria). Author JO subsequently reviewed the references of the publications yielded by the search to identify additional relevant articles. Authors JO, MAH and CSW worked collaboratively to review and categorise each publication in terms of its quality of evidence (Eccles et al., 2001; Moher et al., 2009). The included articles were then summarised with reference to: (1) first study author, year, and country; (2) study design; (3) type of curricula; (4) assessment; and (5) key outcomes related to clinical reasoning (Table 2).

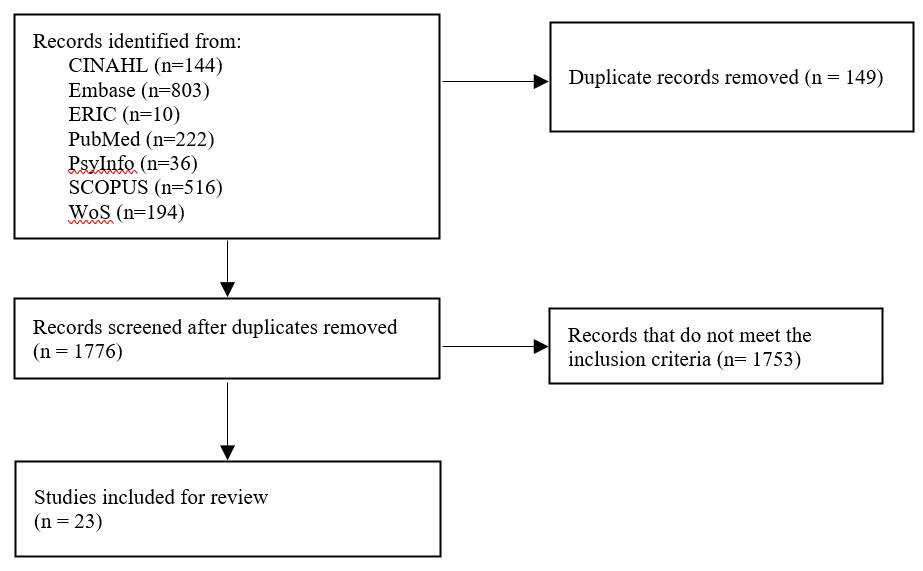

Figure 1. Flow diagram used in search strategy: PRISMA flow chart

III. RESULTS

A. Summary of Search Strategy

The primary literature search generated the most results from Pubmed, Scopus and Google Scholar (Pubmed n=129, Scopus n=28 and Google Scholar n=50). Search results after the first 5 pages on Google Scholar were not considered for inclusion as these pages contained no relevant reports. After the exclusion of duplicates and screening at the title and abstract levels, the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria upon reading the full text of candidate papers resulted in a further 11 reports being excluded on the basis that they did involve

medical students, clinical contexts or had their full texts available. Eleven studies were admitted to the final scoping review (Figure 1).

Table 2 illustrates an overview of each included study. The curriculum was classified based on the teaching methodology described by Fabry et al. (2022), which entailed dividing the typology into group size and didactic principles, i.e., flipped classroom or bed-side teaching. Due to multifaceted teaching concepts, some studies are included under more than one subheading.

|

First author (year, country) |

Study design |

Type of Curriculum |

Assessment |

Key outcome |

|

Gong et al., (2022) China

|

Randomised-Controlled |

Bedside teaching; team-based learning |

Computer-based case simulation; Mini-CEX; Questionnaire |

Creating a role shift to support and develop awareness of diagnostic steps and team-based mutual critical thinking. Significant improvement of satisfaction, clinical judgement, counseling skills in favor of the intervention group.

|

|

Bye et al., (2009) University of Sydney, Australia |

Randomised-Crossover |

Interactive lecture vs. computerised tutorial. |

Expert Observation; Questionnaire |

Interactive lecture was perceived as being more enjoyable, more effective in teaching clinical reasoning than observation. Face-to-face teaching considered critical to maximising the value of computer-assisted self-learning.

|

|

Yousefichaijan et al., (2016) Amir Kabir Hospital, Iran |

Semi-experimental study |

Workshop |

Clinical-reasoning tests (Diagnostic Thinking Inventory (DTI), Key Features and Clinical Reasoning Problems) |

This study emphasises the lack of teaching concepts of medical data acquisition techniques of reasoning steps. Effective example of repeatedly practicing clinical reasoning as a practical skill by working in small groups on illness scenarios of real medical histories.

|

|

Konopasek et al., (2014) New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Graduate Medical Education, New York, NY, USA

|

Experimental study |

Group Objective Structured Clinical Experience (OSCE); practice of communication skills and Multi- Source Feedback (MSF)

|

Questionnaire |

Studies emphasise the relationship between efficient communication skills, diagnostic accuracy, patient adherence, and positive health outcomes. Additionally this approach used problem-solving exercises based on dual-process theory. Students were instructed to consciously work through their first pattern recognition and second hypothesis-data driven clinical assumptions. Significant improvements of self-efficacy, confidence and learning motivation in the post-training scores.

|

|

Rideout & Raszka (2018) University of Vermont Children’s Hospital, USA |

Comparative studies

|

Simulation Case (Hypovolemic Shock in a Child) |

Questionnaire and Evaluation |

Simulation of rapid critical-illness recognition, diagnostic interpretation, decision-making, management, and procedural skills with the motto: learning from your mistakes. Improvements were noted in clinical judgement in critical situations, procedural and team skills.

|

|

Bhardwaj et al., (2022) University of Florida College of Medicine, USA

|

Longitudinal Survey

|

Script Concordance Test (SCT) |

Written Exam: Comparing the SCT to usual clinical assessments |

Significant correlations between SCT, as ambiguous evolving clinical case scenario, and improved decision-making competency and valid assessment items. The SCT facilitated feedback and meaningful conversation about problem-solving insecurities

|

|

Wright et al., (2019) University of Western Australia |

Retrospective study |

Feedback Learning Opportunities (FLO) |

Multi-source feedback |

Prescence of FLOs in complex cases underlines one problem: insufficient clinical information related to clinical reasoning. Advantages shown for systematic feedback-related advice to handle diagnostic and treatment inaccuracies and the learning of alternatives

|

|

Forbes & Foulds (2023) Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada

|

Comparative study |

Team-based learning (TBL) with Key Feature Questions (KFQ) |

Written and oral exam involving KFQ, OSCE and MCQ. Anonymous evaluation |

Significant improvement in KFQ scores. Valuable feedback on team-based approach on KFQ to progress clinical reasoning Ability to experience mistakes and identifying “learning gaps”

|

|

Khera et al., (2020) McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center, USA |

Non-experimental descriptive studies |

Skill session on writing patient assessments

|

Written exam involving Pre- and post-written patient assessments |

Introduction and practice of the efficient usage of semantic qualifiers for key problem summaries. Positive effect demonstrated when practicing the formulation, synthesising, and reviewing of potential differential diagnoses and integration of clinical reasoning.

|

|

Lissinna et al., (2022) Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton Clinic, Canada

|

Qualitative Study |

Pediatric bootcamp using flipped classroom |

Questionnaire and Evaluation |

Positive effects of pre-readings and virtual interactive illness approach on efficiency of clinical data collection, critical-thinking and new mental approach to learning strategies in low stakes environment. Showed possible benefits from the preclinical-clinical transition. |

|

Schmidt & Grigull (2018) Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover (MHH), Germany |

Qualitative Study |

Interactive Serious Game: “Pedagotchi,” for case-based learning; blended learning |

Questionnaire System Usability Scale (SUS) and User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ) |

Motivational and digital additions to traditional lectures. Improved dialogue, real-time feedback and practice of clinical-reasoning in a low-stakes environment. |

Table 2. Overview of reports included in scoping review

B. Source of Studies and Research Design

Included studies came from 6 countries, in general being conducted at university hospitals. The largest group of included studies (n=4) originated in the USA (Bhardwaj et al., 2022; Khera et al., 2020; Konopasek et al., 2014; Rideout & Raszka, 2018). Two articles came from Australia (Bye et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2019) and Canada (Forbes & Foulds, 2023; Lissinna et al., 2022). Single studies were derived from China (Gong et al., 2022), Germany (Schmidt & Grigull, 2018) and Iran (Yousefichaijan et al., 2016).

We categorised the evidence in each publication based on an established evidence hierarchy (Table 3) (Eccles et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 2004). No reviewed study could be aligned to criterion 1a, i.e., evidence from meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Two studies employed a randomised-control design, with Bye et al. conducting a crossover controlled design (Bye et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2022). The method of employing a quasi-experimental study was conducted by two included studies (Konopasek et al., 2014; Yousefichaijan et al., 2016). The majority of included studies could be aligned with category III, i.e., evidence from non-experimental descriptive methods, or more specifically longitudinal surveys (Bhardwaj et al., 2022), retrospective studies (Wright et al., 2019) and qualitative approaches (Forbes & Foulds, 2023; Khera et al., 2020; Lissinna et al., 2022; Rideout & Raszka, 2018; Schmidt & Grigull, 2018).

|

Category of evidence |

Number of studies identified on each rank |

|

Ia: evidence from meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials |

|

|

Ib: evidence from at least one randomised controlled trial |

n=2 Gong et al., 2022; Bye et al., 2009 |

|

IIa: evidence from at least one controlled study without randomisation |

|

|

IIb: evidence from at least one other type of quasi-experimental study |

n=2 quasi-experimental Yousefichaijan et al., 2016; Konopasek et al., 2014 |

|

III: evidence from non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies |

n=7 Longitudinal survey: Bhardwaj et al., 2022 Qualitative study: Lissinna et al., 2022; Khera et al., 2020; Rideout & Raszka, 2018; Forbes & Foulds, 2023; Schmidt & Grigull, 2018. Retrospective study: Wright et al., 2019 |

|

IV: evidence from expert committee reports or opinions and ⁄ or clinical experience of respected authorities |

|

Table 3. Included studies categorised according to levels of evidence defined by Eccles et al. (2001)

C. Summary based on Type of Evidence

The key outcomes derived from the included studies mostly focused on the principle of problem-based learning and can be framed in reference to experiential learning, such as clinical simulation and the acquisition of theoretical reasoning skills (Fabry, 2022; Jensen et al., 2004).

1) Experiential learning: There is evidence, based on the following studies, indicating that a team-based approach of clinical scenarios, with patients or simulated scenarios facilitate the impartation of clinical skills and critical thinking. The role shift towards student-centered learning increases the motivation to actively participate and overcome passive decision-making (Gong et al., 2022). The randomised study by Gong et al. established a division of bedside tasks (i.e., medical history, physical examination, etc.) amongst the case group students. This facilitated knowledge exchange within the team, and enabled both awareness and practice of reasoning steps. Subsequent assessment using computer-based case simulations and the Mini-CEX (Mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise) detected significant improvements in clinical judgment and counselling skills after bedside team-based learning (Gong et al., 2022). In reference to critical thinking, all of the included studies demonstrated a preference for students to encounter and use real cases involving ambiguity, symptom polymorphisms and the possibility of false leads in the context of paediactric practice (Kassirer, 2010).

Forbes and Foulds (Forbes & Foulds, 2023) found that students’ evaluations of team-based learning showed that positive feedback on the ability to use the experiences of mistakes were linked with significant improvements in assessment scores using the Observed Structured Clinical Exam (OSCE).

Similarly, a survey by Rideout and Raszka (Rideout & Raszka, 2018) highlighted that increased team skills can result from feedback exchange and lead to the improvement of communication skills learnt during simulation, including working in intensive ettings and with distressed parents (Konopasek et al., 2014; Rideout & Raszka, 2018). In addition, improved motivation to learn was related to learning in a low-stakes environment (Lissinna et al., 2022; Rideout & Raszka, 2018; Schmidt & Grigull, 2018). Wright et al. reported that student log entries underlined the advantages of feedback-related advice in handling diagnostic and treatment inaccuracies (Wright et al., 2019).

A technique called the Group Objective Structured Clinical Experience used by Konopasek et al. (Konopasek et al., 2014) showed benefits for the learner-centered method through the practice of communication skills in teams during the process of clinical reasoning. This approach brought together experiential learning, multisource feedback and the perspective of dual-process theory in directing students to begin with their recognition of symptoms, then consider hypotheses based on history taking, and information and feedback from multiple parties (Table 2). In a questionnaire-based evaluation such clinical problem solving demonstrated significant increases in self-efficacy and their motivation to learn data gathering techniques (Konopasek et al., 2014).

A further example, Khera et al. (Khera et al., 2020) focused on written patient information prioritisation by using semantic qualifiers to efficiently summarise key problems. Semantic qualifiers are bipolar descriptions of symptoms linked to distil broad medical histories (Norman, 2005). The comparison of pre- and post-intervention evaluation resulted in statistically significant increases in differential diagnosis assessment scores (Khera et al., 2020).

Furthermore, half of the included studies identified multi-source feedback (student, teacher, patient) as being integral to the development of insight into their reasoning and decision-making processes. Feedback itself can proactively influence students’ awareness about their mistakes allowing a meaningful conversation about areas of confusion.

2) Theoretical reasoning skills: Examples of didactic approaches included the use of short-term workshops, flipped classroom teaching, virtual learning experiences, and script-concordance tests. These teaching methods resulted in improved awareness of theory, development of knowledge structures, data prioritisation, and critical thinking (Yousefichaijan et al., 2016). More specifically, half of the studies acknowledged the incorporation of a medical data acquisition technique as being a useful approach to teaching, since diagnostic inaccuracy can be linked with a lack of accurate data gathering (Bye et al., 2009). In reference to these diagnostic techniques, the workshop of Yousefichaijan et al. is an effective example of repeatedly practicing clinical reasoning as a pragmatic skill (Yousefichaijan et al., 2016). Comparing analyses of the Diagnostic Thinking Inventory (DTI) and Clinical Reasoning Problem (CRP) showed significant advantages of working in small groups on illness scenarios (Yousefichaijan et al., 2016). Lissinna et al. (2022) employed a virtual flipped classroom exercise, and then assessed students’ experiences of pre-reading and their practice of efficient sorting of clinically relevant data via semi-structured interviews. The concept of Blended-Learning, as a combination of digital and traditional teaching, embodies the Serious Game approach of Schmidt et al. (2018). The complementary results of Bye et al.’s comparative study, which focused on interactive versus computerised methods of pedagogy, underlines the advantages of the digital addition in the practice of interactive case-based learning with real-time feedback (Bye et al., 2009). In consideration of the aforementioned aspects, the implementation of the Script-Concordance Test that assesses case training, can reveal several advantageous measurements, related to pedagogical techniques using case-based and feedback methods and thus can be regarded as a valid assessment tool (Bhardwaj et al., 2022).

IV. DISCUSSION

A. Clinical Reasoning – A Complex Practical Skill

The findings from this scoping review affirm that clinical reasoning can be described as the mediatory link influencing a clinician’s cognitive multistep process. This process involves knowledge organisation, efficient data gathering, critical data integration culminating in generating a set of reasonable hypotheses, to finally achieve accurate diagnostic interpretation and reflection (Lissinna et al., 2022; Pennaforte et al., 2016; Pinnock et al., 2021). From a data driven perspective, used by novice learners, teaching these reasoning steps separately would likely impair the effectiveness of the reasoning process (Schmidt & Mamede, 2015). At the moment no peer-reviewed paediatric curricula guidelines focus on active educational experience of clinical reasoning. Additionally, short paediatric rotations only allow limited practice of common paediatric diagnoses (Madduri et al., 2024).

Consistent with Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence learning clinical skills effectively, involves promoting practice by doing, along with frequent repetition (Fabry, 2022; Miller, 1990). In reference to the dual-process model, repetition moves much of the cognitive effort involved in understanding the relevant illness presentation from system 2 to the pattern recognition abilities of system 1 (Yazdani et al., 2017). Considering clinical reasoning as a practical skill, student passivity is the reason why it is relatively difficult to attain a high level of competency (Forbes & Foulds, 2023). Ulfa et al. (2021) used a randomised control trial comparing lecture vs. team-based learning of postpartum hemorrhage of midwifery students. The results indicated the superiority of active team-based methods on the development of independent and effective critical-thinking abilities. This suggests substantial benefits for a paediatric curricula configuration that involves implementation of more active learning experiences starting in the pre-clinical years in the form of mixed teaching strategies (Forbes & Foulds, 2023; Jost et al., 2017; Koenemann et al., 2020). Jost and colleagues observed significantly improved clinical reasoning performance with Team-Based Learning groups in an undergraduate neurology course using key-feature examination (Jost et al., 2017).

B. Mix of Teaching Methods

In reference to this scoping review’s aim, we can identify the advantages of combining different teaching styles. Lectures remain the fundamental method used to convey basic scientific knowledge, which can be an essential precondition for using more practical teaching methods. The findings indicated that improvements of the decision-making process were first identified by theory presentation, i.e., teaching dual-process theory and its links to common cognitive pitfalls and the potentially significant adverse consequences for paediatric clinical reasoning (Schmidt & Mamede, 2015). However, lectures also have didactic disadvantages, which include teacher-centered explanations with less activation and linking of previous knowledge and may create cognitive overload in learners (Fabry, 2022). There are different options to overcome this by promoting active pre-class learning and open discussions about information processing ambiguities (Lissinna et al., 2022). For example, the use of the flipped classroom approach can improve clinical understanding and increase the motivation to learn in contrast to lecture-based approaches (Tang et al., 2017). The crossover study of Tan et al. (Tan et al., 2016) also indicated superior problem-solving ability attributed to team-based learning in comparison with interactive lectures. Similarly, Jackson et al. (Jackson et al., 2020) demonstrated a significant increase in satisfaction when using critical thinking and promoting student self-directed learning when attending an online team-based learning module in a family medicine rotation.

C. Clinical Reasoning and Clinical Cases

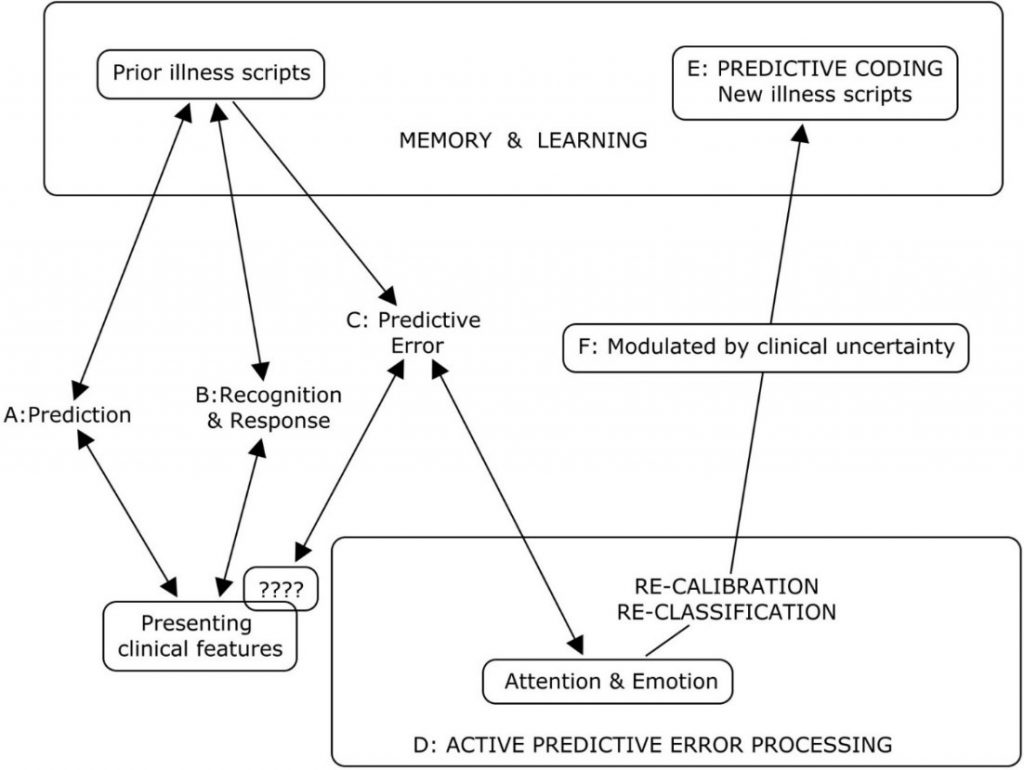

The simulation of clinical judgment can be enhanced using an evolving clinical scenario (Fabry, 2022). The focus on improvement of clinical judgment in paediatrics can be justified by a unique interaction of fine perception and empathy of the child’s clinical problem. In particular, the practice of effective communication plays a critical role in the analyses of symptoms when in discussion with parents and children. Since both are overlaid with anxiety, this adds to the diagnostic challenge. This requires experiential learning, for example by the careful student-centered bedside practice of communication with anxious and vulnerable families. This can increase students’ awareness of emotional messages and changes in the patient. The link of promoting empathy by teaching problem-solving plays a critical role in paediatrics (Gong et al., 2022). One example, could be the use of Illness scripts, describing an approach to synthesising patient history into a meaningful flowchart. Levin et al. and Konemann et al. showed students’ motivation working on real complex cases embodying a step-by-step information disclosure approach (Koenemann et al., 2020; Levin et al., 2016). Interestingly, Schmidt and Mamede also described these two opposing ways to present clinical cases, calling them “serial-cue” vs. “whole case” methods (Schmidt & Mamede, 2015). The studies included in this review emphasised students’ challenges with obtaining the correct collection of critical information for a stepwise disclosure in paediatrics.