Emergency medicine clerkship goes online: Evaluation of a telesimulation programme

Submitted: 30 August 2020

Accepted: 9 December 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 56-66

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/OA2440

Gayathri Devi Nadarajan1, Kirsty J Freeman2, Paul Weng Wan1, Jia Hao Lim1, Abegail Resus Fernandez2 & Evelyn Wong1

1Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore; 2Office of Education, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: COVID-19 challenged a graduate medical student Emergency Medicine Clinical Clerkship to transform a 160-hour face-to-face clinical syllabus to a remotely delivered e-learning programme comprising of live streamed lectures, case-based discussions, and telesimulation experiences. This paper outlines the evaluation of the telesimulation component of a programme that was designed as a solution to COVID-19 restriction.

Methods: A mixed methods approach was used to evaluate the telesimulation educational activities. Via a post-course online survey student were asked to rate the pre-simulation preparation, level of engagement, confidence in recognising and responding to the four clinical presentations and to evaluate telesimulation as a tool to prepare for working in the clinical environment. Students responded to open-ended questions describing their experience in greater depth.

Results: Forty-two (72.4%) out of 58 students responded. 97.62% agreed that participating in the simulation was interesting and useful and 90.48% felt that this will provide a good grounding prior to clinical work. Four key themes were identified: Fidelity, Realism, Engagement and Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes Outcomes. Limitations of telesimulation included the inability to examine patients, perform procedures and experience non-verbal cues of team members and patients; but this emphasised importance of non-verbal cues and close looped communication. Additionally, designing the telesimulation according to defined objectives and scheduling it after the theory teaching contributed to successful execution.

Conclusion: Telesimulation is an effective alternative when in-person teaching is not possible and if used correctly, can sharpen non-tactile aspects of clinical care such as history taking, executing treatment algorithms and team communication.

Keywords: Telesimulation, COVID-19, Emergency Medicine, Programme Evaluation

Practice Highlights

- Telesimulation doesn’t replace but can be an effective alternative when in-person teaching is not possible.

- When implemented correctly, it can sharpen non-tactile aspects of clinical care.

- It is possible to achieve a level of fidelity and realism in a telesimulation environment.

- Simulation faculty needs to be skilled in debriefing techniques that enable the learner to reflect.

- Limitations of telesimulation can be reframed as learning opportunities.

I. INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 brought about unexpected challenges to medical education, especially to student clinical clerkships where medical students would spend time within a clinical discipline, interacting with clinicians and learning from patients. Healthcare institutions restricted student movement within clinical environments and barred students from entering the high-risk frontline areas to reduce exposure risk.

Prior to COVID-19, students undertaking an Emergency Medicine (EM) Clinical Clerkship, would have the opportunity to manage and deliver care to high acuity patients, with bedside teaching, small group tutorials, problem-based learning and simulation modalities. With COVID-19, students were not permitted into the Emergency Department (ED) and face-to-face teaching activities were halted. Hence this clerkship had to be conducted remotely. The EM clerkship was transformed from a 160-hour clinical programme to a remotely administered programme comprising 40 hours of e-learning, 40 hours of interactive live online session and 15 hours of telesimulation. As part of this programme, we decided to utilise telesimulation to help students achieve some of the objectives of a clinical clerkship.

Telesimulation is defined as the “Process by which telecommunication and simulation resources are utilised to provide education, training and/or assessment to learners at an off-site location” (McCoy et al., 2017). By allowing simulation to be conducted through devices such as the computer and phone, it mitigates the problem of physical proximity. Though telesimulation has existed for about a decade, its utilisation appears limited to the rural settings and studies mainly describe its usage for learning skills (Mikrogianakis et al., 2011; Naik et al., 2020; Okrainec et al., 2010) rather than for emergency management of patients. With the need to adapt teaching to remote experiences, telesimulation is gaining popularity (Sa-Couto & Nicolau, 2020).

A. Programme Overview

This remote learning programme was developed in a tertiary ED in Singapore which receives both undergraduate and postgraduate medical students for their EM clerkship. There were 58 postgraduate medical students undertaking their 4-week EM clerkship in June 2020. The EM core clinical training curriculum was taught by EM faculty via online modules and interactive classroom sessions delivered via the video conferencing platform, Zoom. The learners spent the mornings in interactive online sessions with faculty, and afternoons in self-study as part of a flipped classroom learning, using provided learning materials. The telesimulation session was scheduled in the last week, over five days. The students were split into ten groups each comprising of five to six students, where two groups participated in one telesimulation session each day.

Our objectives for this telesimulation programme was to ensure that the students could take a focused clinical history from the simulated patients, communicate with them, construct a list of differentials and manage them accordingly in the emergency setting. The secondary objectives were to train them to prioritise the investigations and management of critically ill patients and to communicate and work effectively within a team. Using Kern’s six step approach, the team of simulation and clinical educators’ planned and implemented the telesimulation activity to achieve these outcomes (Harden et al., 1999; Smith & Dollase, 1999) during their EM clerkship.

As medical students, the learners are at a novice stage according to The Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition (Benner, 2004; Dreyfuss & Dreyfus, 1980). Hence, the deliberate attempt not to assess skills such as intubation or defibrillation through telesimulation as it may create unnecessary anxiety and feelings of incompetence (Papanagnou, 2017). Furthermore, it was deemed challenging to conduct procedural skill teaching through this modality. Instead, the focus was on clinical reasoning and patient management. The clinical students fall under the category of “show how” within the Miller’s pyramid, with regards to history taking, clinical reasoning and management. As adult learners, a problem centred (Knowles, 1990), experiential learning approach (Kolb, 1984) would be more valuable. Hence telesimulation was an appropriate modality.

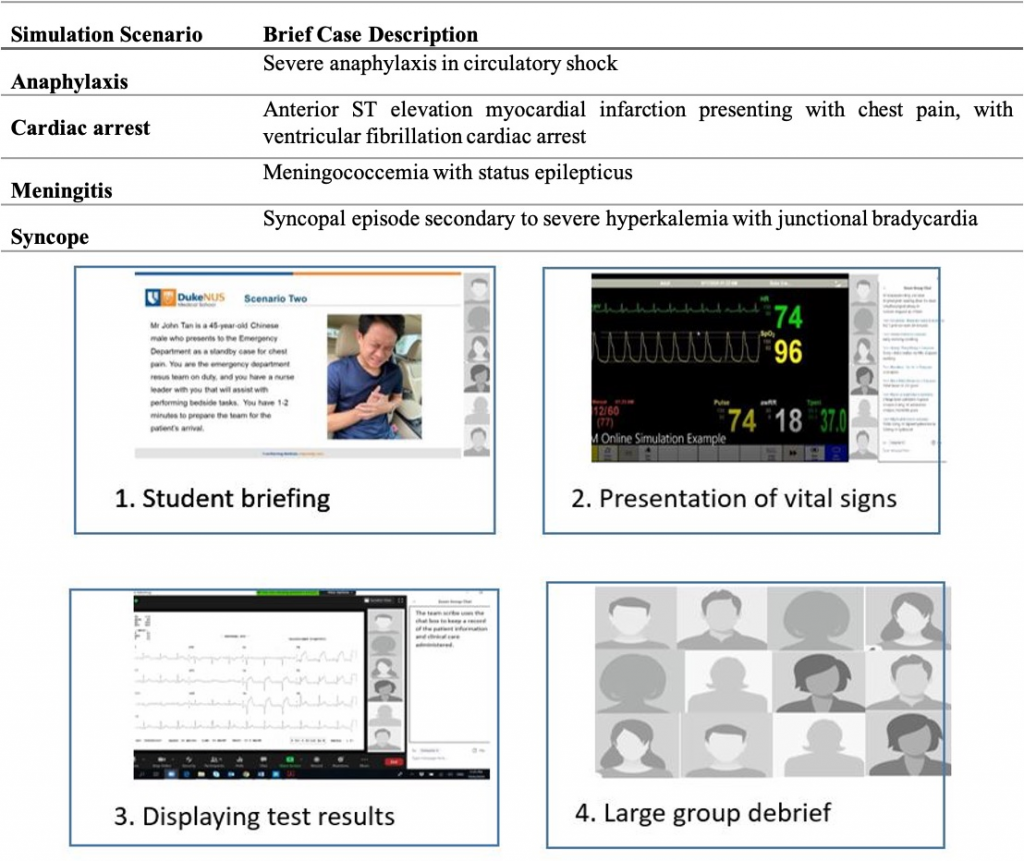

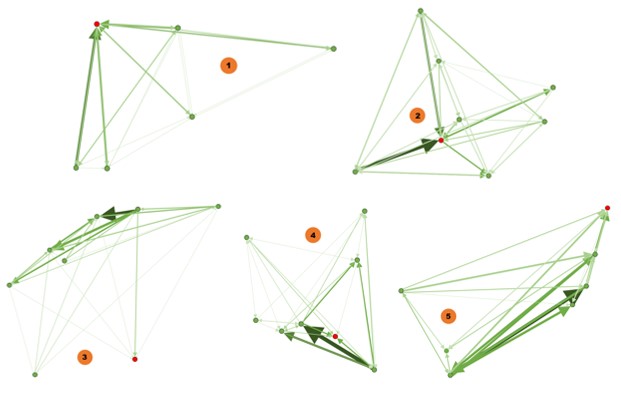

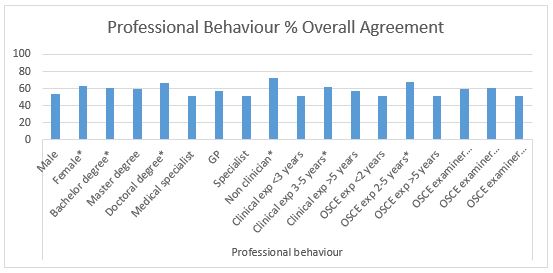

Each telesimulation session was conducted by two simulation and one physician faculty. There was a total of four scenarios for each session, where one group, consisting of five to six students, will participate in the scenario, while the other group observes, before switching. This allowed each group of students to participate in two clinical scenarios. The topics chosen for telesimulation were Anaphylaxis, Cardiac Arrest, Meningitis, and Syncope where the theory was covered in the core topics in the preceding weeks. Each of these scenarios began with the students taking a history from the simulated patient, before the patient progressively deteriorated and required resuscitation. Figure 1 shows a summary of the scenarios. The scenarios were selected as they did not require much procedure-based interventions (e.g. chest tube insertion in a poly trauma victim) which would be difficult to assess via Zoom.

Figure 1. Brief case description of simulation scenarios and visual presentation of the flow of the telesimulation experience

The sessions commenced with a briefing where the students were orientated to the online environment, including the use of video and microphones. As depicted in Figure 1, using the share screen feature, the simulation technician switched between different views. The briefing included a photo of the patient as a visual cue, along with the text of the presenting case. One of the simulation faculty played the circulating nurse, providing prompts to aid students’ engagement and asking participants to clarify their statements or orders as the scenario progressed. Using existing mannequin software and ensuring sharing of screen sounds, real-time patient monitoring was provided to the learners when requested. Upon request, additional visual cues of investigation results would be displayed, reverting back to either a picture of the patient or the patient monitoring. With their video off, the clinical faculty voiced the patient. At the conclusion of the scenario, all participants and faculty turned their video and microphones back on to participate in the large group debrief before proceeding on to the next scenario.

The objective of this paper is to describe the students’ experience of telesimulation as part of an online clerkship programme and how such techniques can be used to meet learning outcomes (Harden et al., 1999) in various settings. At the time of writing, there is no literature describing evaluation of the use of a telesimulation programme within the ED for medical student education, with this paper aiming to address this gap.

II. METHODS

A mixed methods approach was used to evaluate the introduction of telesimulation to the EM online clerkship, and to gain students’ perspective on learning through telesimulation. Programme evaluation research aligns with a mixed methods approach as the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data provide a deeper understanding of the student experience (Cohen et al., 2011).

A. Participants, Data Collection and Analysis

58 final year medical students who participated in the EM Online Clerkship programme were invited to participate in a post-telesimulation activity evaluation survey. Using a 5-point Likert scale, students were asked to indicate their agreement on 11 items addressing pre-simulation preparation, their level of engagement, confidence in recognising and responding to the four clinical presentations and telesimulation as a tool to prepare for working in the clinical environment. Seven open-ended questions were asked to enable the students to describe their experience in greater depth. 24hrs after completing the telesimulation session, students received an email with a link to the survey. Qualtrics online survey software was used to build, distribute and collect the survey responses. Voluntary consent was assumed by participation in the anonymised online evaluation. A statement outlining the purpose of the survey was included at the start of the survey and require an agreement before the survey could be commenced. Completion of the survey therefore implied consent. The survey took between three and five minutes to complete, all responses were anonymous, with no identifiable data collected.

Descriptive statistics was used to analyse the responses to the Likert scale questions, with thematic analysis of the open-ended survey questions. Author one (GN) and author two (KF) reviewed the transcripts separately, making note of key phrases, outline possible categories or themes. Both authors then jointly rearranged and renamed the codes, developing higher order themes. NVivo 12™ was used to store, code and manage the qualitative data.

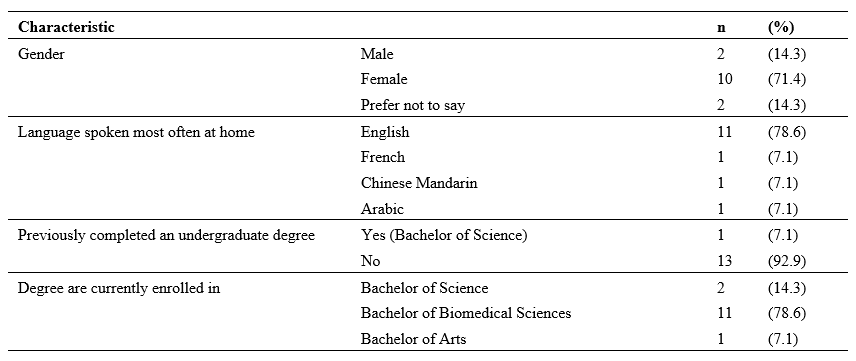

III. RESULTS

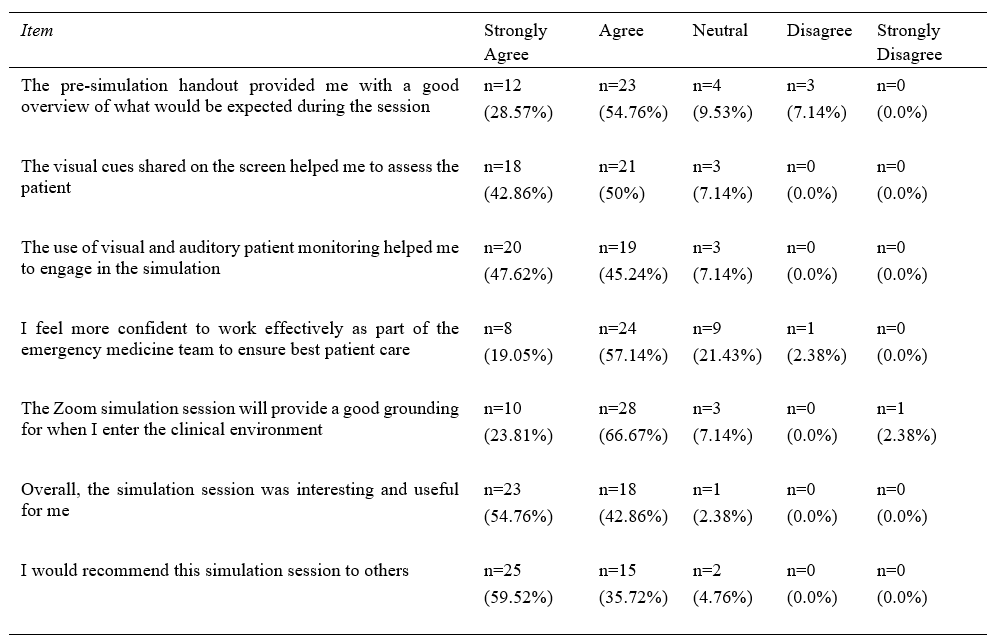

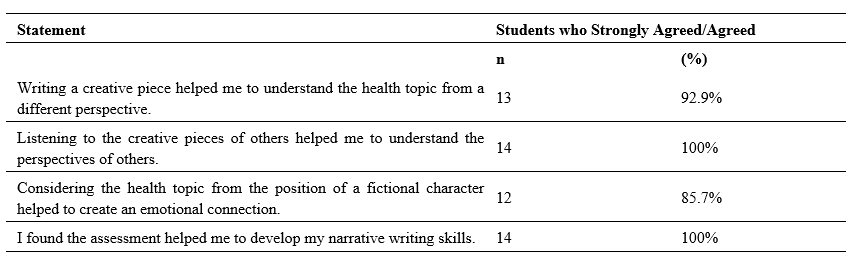

Of the 58 students who were invited to participate in the survey, 42 complete responses were received, a response rate of 72.4%. As seen in table 2, the results demonstrated that 97.62% of respondents agreed/strongly agreed that participating in the telesimulation session was interesting and useful to their learning. In relation to the use of visual and auditory cues, 93% of respondents felt that these helped them engage in the simulation. In relation to their level of preparedness to participate in the telesimulation experience, nearly 17% of respondents reported that the pre-session handout did not adequately preparing them for what to expect in the session.

Table 1. Results of the student responses to the Likert scale items

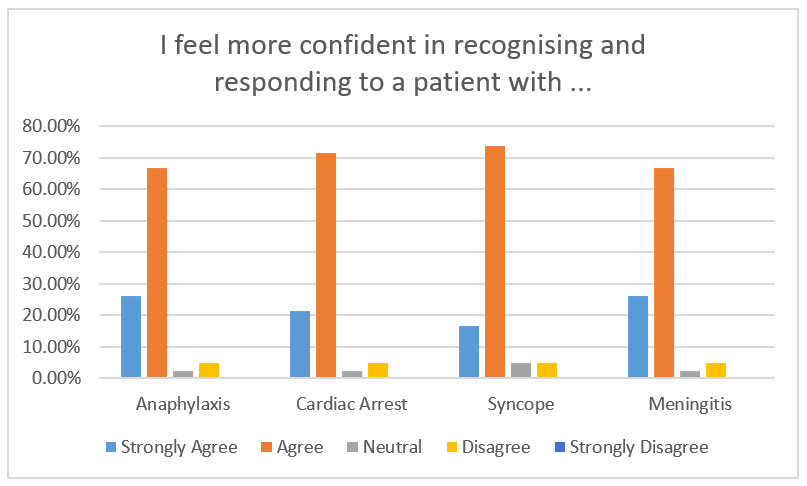

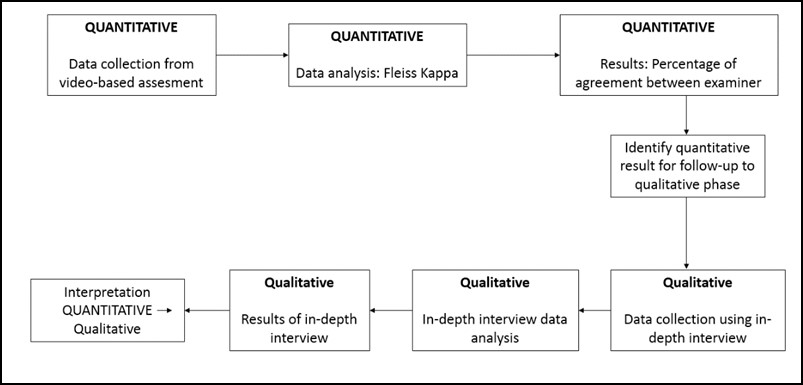

When asked to rate if they felt more confident recognising and responding to the four clinical presentations (anaphylaxis, cardiac arrest, meningitis, and syncope), between 90% and 93% agreed/strongly agreed that participating in the telesimulation sessions resulted in them feeling more confident in recognising and responding to the specific clinical presentations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Student rating to the question “I feel more confident in recognising and responding to a patient with …”

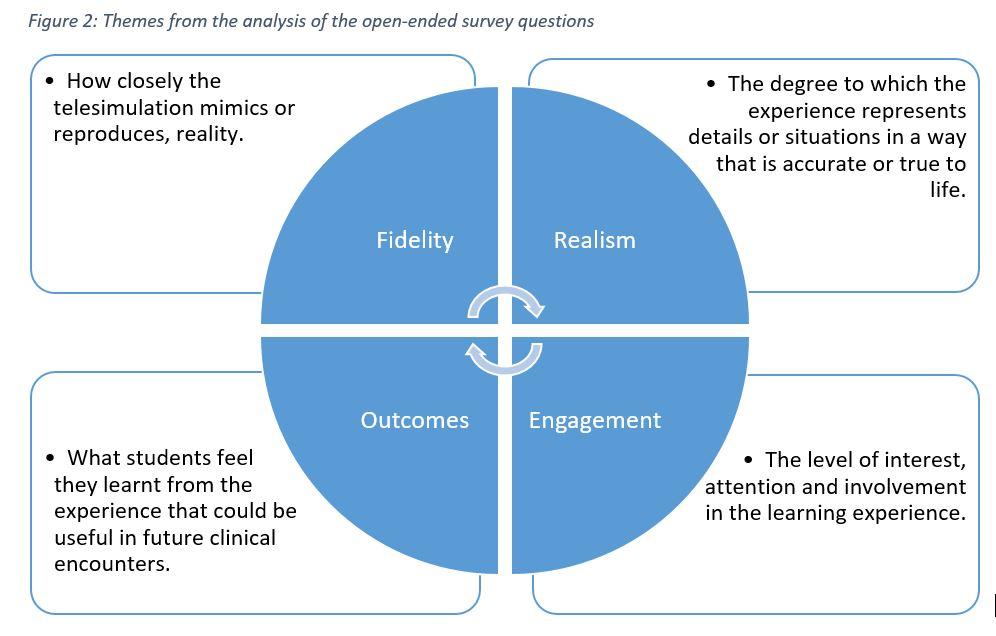

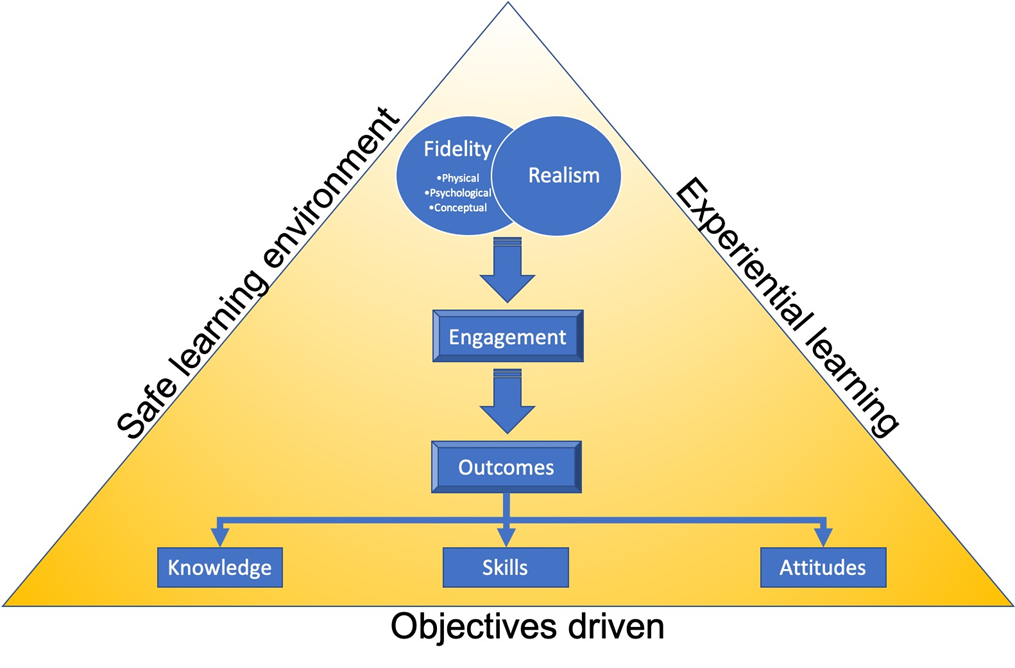

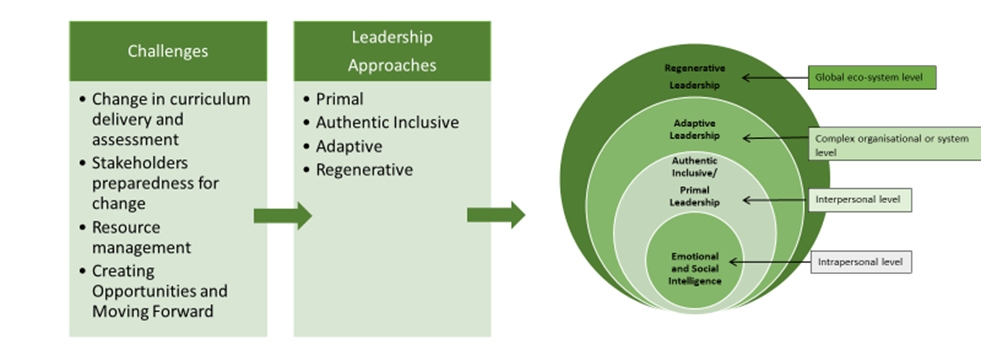

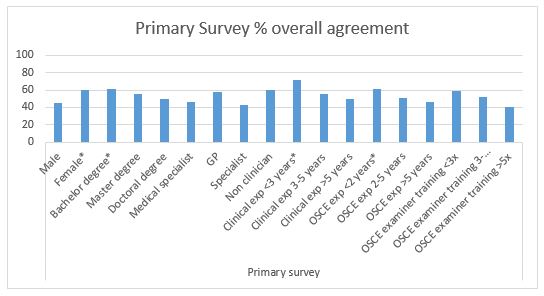

Four key themes were identified following the data analysis of the open-ended survey questions, describing around the telesimulation experience of the respondents: 1) Fidelity; 2) Realism; 3) Engagement; and 4) Outcomes. As demonstrated in Figure 3, the themes do not exist in isolation, but intersect as they describe the telesimulation experience that the students had. The students feedback reflected the benefits and limitations which fall under these main themes.

Figure 3. Themes reflecting the students experience with telesimulation

A. Fidelity – Physical, Psychological and Conceptual

The theme Fidelity reflects how closely the telesimulation mimics or reproduces, reality. Subthemes of conceptual, physical and psychological fidelity were also reflected. The students’ feedback reflected limitations in physical fidelity while conceptual and psychological fidelity was present mostly.

They reported that the auditory and visual stimulus from the dynamic display of investigations and real-time vital signs monitoring, provided a high level of physical fidelity.

“Auditory and visual information on patients’ vitals and results were really helpful in generating the differential list.”

Student 37

“The noise and sights is a good proxy for real life cases in a virtual environment.”

Student 4

“Seeing the vitals of the patient in real-time allows us to experience the importance of time in managing critically ill patients”

Student 20

However, aspects of physical fidelity, particularly related to the patient assessment, were reported as challenging via telesimulation. With the patient represented as a static picture, voiced by the clinical faculty, students shared how the lack of non-verbal and visual cues from the patient impacted their ability to perform a physical assessment of their patient.

“….we don’t get to observe the body language of the patient as much as we would like”

Student 12

“More difficult than in real life. Seeing and hearing a real patient gives much information”

Student 15

“I think what is lacking is being able to visually evaluate the patient”

Student 21

In terms of the level of psychological fidelity, the auditory cues from the ‘patient’ and the real-time vital signs monitoring simulated the ED resuscitation room, which appears to have instilled a similar sense the stress and the need to think under pressure, as reflected by the students’ feedback.

“Have to work around the distractions of beeping monitors, seizing patient, teammates asking questions/suggestions.”

Student 33

“It’s dynamic and gives us the opportunity to think under pressure.”

Student 13

“Stressful but probably close to reality?”

Student 35

The students’ statements reflected the subtheme of conceptual fidelity, where they felt the context and sequence was similar to what they would encounter in the ED, where they are required to deliver timely and lifesaving treatment. This was possibly because the faculty made deliberate attempts to ensure that events during the simulation would unfold as it usually would in the ED room, based on the learners’ actions.

“It simulates a clinical environment with real time updates of vitals and test results in addition to the history and communications.”

Student 5

What the students did report struggling with however, was the limitations of the platform in terms of multiple actions occurring simultaneously. Unlike in real life, multiple tasks could not be performed at the same time over the online platform, and this impeded the conceptual fidelity.

“In reality, multiple interventions would be carried out in tandem.”

Student 35

“More challenging to perform tasks concurrently over Zoom.”

Student 36

“…many things cannot occur concurrently.”

Student 2

B. Realism

The theme Realism captures the degree to which the experience represented details or situations in a way that is accurate or true to life. Students reported that aspects of the telesimulation experience represented what they thought an actual ED encounter would be like.

“I think the process is similar to the actual clinical environment, it is difficult, especially when the patient is deteriorating in front of you, and your team are waiting for you to make the decisions.”

Student 41

“The pictures/videos and the beeping of the monitor, they make it more real”.

Student 42

“It was realistic as getting the differentials was time sensitive”.

Student 13

The students also acknowledged the limitations in achieving realism presented by telesimulation as the various team members could not perform tasks simultaneously and take in cues from the patient to assess the outcome of their actions.

“Harder to communicate with my teammates compared to real life because only one person could speak at a time while in real life, multiple conversations could be occurring”

Student 3

“More difficult than taking a history in real life – more technical issues (can’t hear properly), Can’t see the patient”

Student 8

C. Engagement

The theme Engagement relates to the level of interest, attention and involvement in the learning experience. The level of fidelity and realism impacts the level of engagement of the learners. Most students were able to immerse themselves and fully engage in the scenarios, possibly because aspects of fidelity and realism were deliberately given close attention during the preparation phase.

“I actually forgot that the patient was being voiced by the clinical tutor”

Student 41

“My heart was racing doing the simulation – what will I be like when I am there for real?”

Student 41

However, on the downside, without being together in the same place, some felt that the scenario was too “messy” and “chaotic” and found it difficult to follow.

“It was a little hectic with the many other ongoing tasks in the background”

Student 6

“Easier to detach oneself from the patient (less affected by patient’s appearance, tone of voice, blood, gore, suffering etc.)”

Student 28

At the same time, some students faced technical difficulties, such as small or flickering screen, poor internet connection or poor audio, which were barriers to their engagement.

“…there were some issues hearing the faculty clearly which may affect the quality of learning.”

Student 6

By addressing the concepts of realism and fidelity, the students reported increased levels of engagement, although it appears that technical barriers unique to telesimulation provide challenges for some students achieving a greater level of engagement.

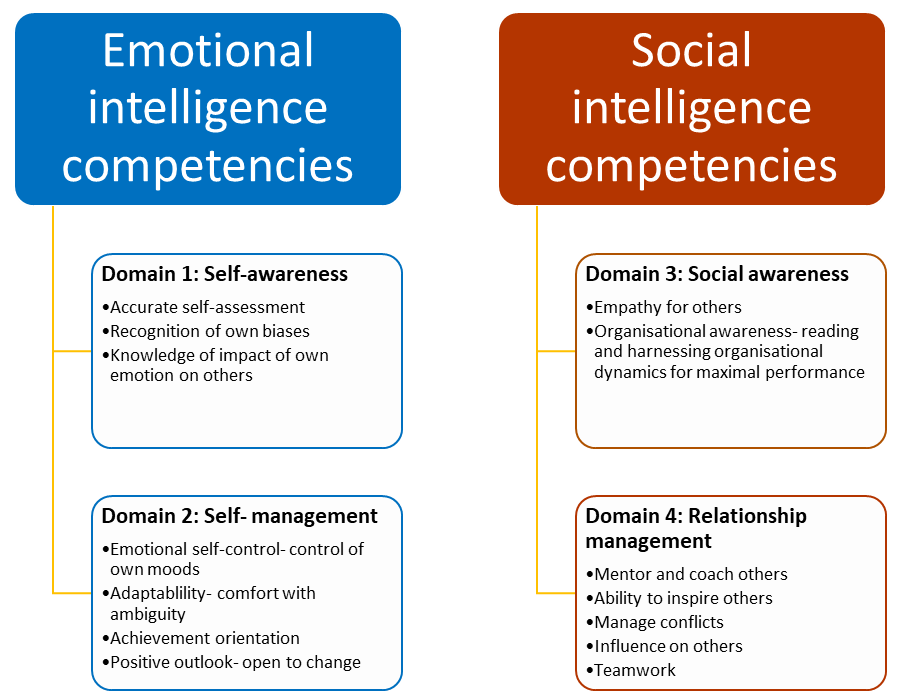

D. Outcomes- Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes

The theme Outcomes encompasses what students feel they learnt from the experience that could be useful in future clinical encounters. Under outcomes, there were sub-themes of knowledge, skills and attitudes. From a knowledge perspective, students reported that the telesimulation reinforced their clinical reasoning to arrive at a differential list.

“It was very useful and helped with our clinical reasoning. It was also useful in learning how to generate differential diagnoses as a team and going down the path of a working differential diagnosis while keeping others in mind.”

Student 32

Whilst the lack of hands-on practice was acknowledged, the telesimulation environment required them to practice the skills of prioritisation, leadership, teamwork and effective, close loop communication to manage the patient and this accounted for their skills gained.

“I will be able to apply the concept of teamwork, thinking on my feet, thinking broad, and constant reassessment of the unstable patient in my clinical training over the next few months”

Student 6

“Stay calm, go back to first principles, have the approach at your fingertips, make an effort to remember drug doses and administration route”

Student 2

IV. DISCUSSION

In relation to Kirkpatrick’s model for evaluating educational outcomes, the results of this study (table 1) demonstrate achievement of both level one (reactions) and level two (learning) outcomes (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2009). Whilst these findings may not determine the effectiveness of telesimulation, it does however provide insight into the learners’ experience that have highlighted the strengths and limitations of telesimulation, which the authors of this paper believe provides a foundation upon which others can build.

It is well documented in the simulation literature that fidelity and realism are important concepts that need to be considered when planning simulation-based education (Oliver, 2002). And this was an initial concern by the educators. The lack of a physical ‘patient’ on which to carry out procedures and physical examination could limit the effectiveness of the telesimulation experience. To address this limitation, faculty briefed the learners about the limitations and the strategies, such as the use of a ‘nurse confederate’ to provide clinical information, as well as having visual cues such as pictures and videos to trigger their actions. Interestingly, the feedback suggests that the lack of a physical ‘patient’ to examine, resulted in more emphasis being placed on the audio and visual cues during the session. This allowed the learners to proactively compensate for the lack of tactile cues with audio and visual ones, reinforcing the importance of clinical alerts and alarms. The inability to perform a physical examination provided an opportunity for the debriefer to emphasise the importance of the skill in clinical care.

There was a deliberate attempt to create scenarios that were commonly seen in the ED in as much details as possible to achieve realism in the virtual space. This limited the scenarios that could be used as we had to use ensure procedures were not required for the patient management to progress (for example, trauma was deemed inappropriate). The faculty feel that the typical, non-complex ED scenarios compounded with the sequence of events as it would occur in real life possibly contributed to the student’s perception of realism during the telesimulation.

Instructional scaffolding was key to student engagement. The faculty configured the telesimulation session to be held after three weeks of interactive and didactic sessions on Zoom. This allows the learners to acquire essential knowledge which they can then apply during the telesimulation session. With the background baseline knowledge, the telesimulation setup and audio and visual prompts of a real ED environment, the faculty felt that they were able to immerse the students within the scenario rather than conducting it as an online Problem-Based-Learning session. This may have contributed to their engagement.

Communication skills were a common thread reported by the students, both positively and negatively in many of their statements. They described the shortcomings of communication over Zoom and felt that the session highlighted how non-verbal cues and the physical presence influences the way one communicates. At the same time, the absence of visual and tactile stimuli forced them to practice good communication to get their points across when managing the patients.

Interestingly, though many students scored high on the Likert scale about feeling confident in managing emergencies, with the open-ended questions, they reflected feelings of nervousness, fear and a lack of confidence to working in the ED, showing that perhaps this cannot replace patient contact.

Cognisant of the limitations of telesimulation, most of the learners enjoyed the session. This may have been due to the novelty of it and ED room mimics such as the beeping of the monitors and the realistic scenarios. Faculty also realise that the limitations of telesimulation and used them as discussion points to highlight elements that one may take for granted during their patient encounters, such as the non-verbal cues and the tactile stimuli.

Key to this successful telesimulation session was establishing realistic and focused objectives (Harden et al., 1999). Failing to recognise that telesimulation differs from conventional simulation and therefore emphasising on tactile skills such as procedures and physical examination will minimise the effectiveness of the session. Knowing the inherent limitations helped faculty to prepare holistically for the session. Learning objectives focused on non-tactile aspects, such as history taking and executing treatment algorithms. In addition, as tactile cues are limited in the telesimulation setting, all other cues such as visual and audio were optimised.

Debriefing during the telesimulation sessions has an even more vital role in student learning compared to conventional simulation sessions (Fanning & Gaba, 2007). The debriefer not only has to highlight salient clinical points regarding the case, but also probe learners to think about limitations of the telesimulation modality. Therein, understanding the importance of highlighting tactile and visual feedback. For example, one learner recognised that he was “unable to visually observe and direct the teammate”; another came to the conclusion that “being able to see the patient and physical expression of fellow doctors/nurses is crucial”. This allows the educator to discuss the importance of situational awareness and non-verbal cues in enhancing team dynamics. However, if the debriefer fails to address this limitation, the learners may leave the session feeling dissatisfied or inadequate with their performance at the session. The uniqueness of telesimulation adds another facet to debriefing where the debriefer needs to be able to address the limitations of telesimulation and relate it back to clinical relevance. Therefore, there might be a need to provide additional training for educators in debriefing telesimulation sessions.

Simulation-based training is an effective modality to teach procedural skills, put into practice treatment algorithms and hone soft-skill relevant to team dynamics. (Lateef, 2010; Sirimanna & Aggarwal, 2014). As demonstrated through this innovative programme, it has an important role to play in medical education during such a pandemic where it might be used to mitigate the negative educational impact of no patient contact, team-based training and protocol development and testing (Chaplin et al., 2020; Dieckmann et al., 2020). All this is done within a psychologically and physically safe environment.

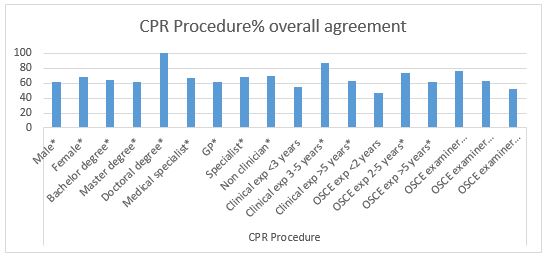

Based on the feedback collected, a conceptual framework below (Figure 4) was drawn, showing the relationship between the concepts of fidelity and realism in the telesimulation experience to the level of engagement and therefore outcomes perceived by the learners. This is supported by the objectives, experiential learning and a safe learning environment.

Figure 4. Conceptual framework

V. CONCLUSION

The role of face-to-face interactions with patients and immersing oneself in the acute care environment in bridging the theory to practice gap experienced by all healthcare students is essential to their clinical training. The restrictions encountered due to COVID-19 have required clinical educators to be agile and innovative in their approach the clinical clerkships. The EM clerkship telesimulation programme set out to provide an avenue for medical students to hone their clinical skills (history taking) and clinical reasoning (deriving differential diagnosis) in a safe environment. The evaluation of this programme has highlighted key areas of telesimulation which educators need to consider when planning to use it. The feedback from the students is promising and it highlights certain teaching points which may not be reflected upon during in-person simulation. Educators who wish to implement a telesimulation programme should pay particular attention to the learning objectives and debriefing methods. Whilst this paper has outlined how telesimulation can be implemented during a pandemic, it is envisaged that educators from other healthcare disciplines could use these findings to support the adoption of telesimulation in a variety of educational contexts. Telesimulation is a good alternative in settings such as this pandemic or during distance training programmes and may be a convenient way to hone history taking, clinical reasoning and communication skills without the use of an expensive simulation laboratory. The modality needs to meet the learning objectives and the debriefing should be adopted for telesimulation. However, the authors/faculty feel it cannot replace the full benefits of in-person simulation or learning from direct patient contact.

Notes on Contributors

Gayathri Devi Nadarajan and Kirsty J Freeman conceptualised the article, undertook the thematic analysis, contributed to article sections, and reviewed and revised manuscript based on suggestions from the other authors.

Lim Jia Hao, Wan Paul Weng and WONG Evelyn contributed to the conceptualisation of the paper, contributed to the article sections, reviewed and revised drafts.

Abegail Resus Fernandez undertook the quantitative analysis, and reviewed drafts.

All authors were involved in the development and delivery of the EM Clerkship Telesimulation Programme. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) granted an exemption, CIRB Ref. No.: 2020/2719, as this study was assessed as a quality improvement project.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thanks the students who participated in this unit and their willingness to adapt to the online platform with grace and enthusiasm.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Benner, P. (2004). Using the dreyfus model of skill acquisition to describe and interpret skill acquisition and clinical judgment in nursing practice and education. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society, 24(3), 188–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467604265061

Chaplin, T., McColl, T., Petrosoniak, A., & Hall, A. K. (2020). Building the plane as you fly: Simulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 22(5), 576–578. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2020.398

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203720967

Dieckmann, P., Torgeirsen, K., Qvindesland, S. A., Thomas, L., Bushell, V., & Langli Ersdal, H. (2020). The use of simulation to prepare and improve responses to infectious disease outbreaks like COVID-19: Practical tips and resources from Norway, Denmark, and the UK. Advances in Simulation, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-020-00121-5

Dreyfuss, S. E., & Dreyfus, H. L. (1980). A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Berkeley. https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a084551.pdf

Fanning, R. M., & Gaba, D. M. (2007). The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simulation in Healthcare, 2(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180315539

Harden, R. M., Crosby, J. R., & Davis, M. H. (1999). AMEE Guide No. 14: Outcome-based education: Part 1 – An introduction to outcome-based education. Medical Teacher, 21(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599979969

Kirkpatrick, D. L., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2009). Evaluating: Part of a ten-step process. In evaluating training programs. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Knowles, M. S. (1990). The adult learner: A neglected species. Gulf Publishing Co.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). The process of experiential learning. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (pp. 20-38). Prentice Hall.

Lateef, F. (2010). Simulation-based learning: Just like the real thing. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, 3(4), 348. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2700.70743

McCoy, C. E., Sayegh, J., Alrabah, R., & Yarris, L. M. (2017). Telesimulation: An innovative tool for health professions education. Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training, 1(2), 132–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10015

Mikrogianakis, A., Kam, A., Silver, S., Bakanisi, B., Henao, O., Okrainec, A., & Azzie, G. (2011). Telesimulation: An innovative and effective tool for teaching novel intraosseous insertion techniques in developing countries. Academic Emergency Medicine, 18(4), 420–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01038.x

Naik, N., Finkelstein, R. A., Howell, J., Rajwani, K., & Ching, K. (2020). Telesimulation for COVID-19 Ventilator management training with social-distancing restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic. Simulation and Gaming, 51(4), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878120926561

Okrainec, A., Henao, O., & Azzie, G. (2010). Telesimulation: An effective method for teaching the fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery in resource-restricted countries. Surgical Endoscopy, 24(2), 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0572-6

Oliver, R. G. (2002). Simulation-based medical education. In R. M. Harden & J. A. Dent (Eds.), A practical guide for medical teachers (4th ed., Vol. 29, Issue 2, pp. 226–233). Churchill Livingstone.

Papanagnou, D. (2017). Telesimulation: A paradigm shift for simulation education. Academic Emergency Medicine Education and Training, 1(2), 137–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10032

Sa-Couto, C., & Nicolau, A. (2020). How to use telesimulation to reduce COVID-19 training challenges: A recipe with free online tools and a bit of imagination. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000129.1

Sirimanna, P. V., & Aggarwal, R. (2014). Patient safety. In Levine, A., DeMaria, S., Jr., Schwartz, A. D., & Sim. A. J. (Eds.). The comprehensive textbook of healthcare simulation. Springer.

Smith, S. R., & Dollase, R. (1999). AMEE guide No. 14: Outcome-based education: Part 2 – Planning, implementing and evaluating a competency-based curriculum. Medical Teacher, 21(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421599979978

*Gayathri Devi Nadarajan

Department of Emergency Medicine

Singapore General Hospital

1 Outram Road, Singapore 169608

Tel: +65 96804724

Email: gayathri.devi.nadarajan@singhealth.com.sg

Submitted: 14 August 2020

Accepted: 6 November 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 45-55

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/OA2377

Nathalie Khoueiry Zgheib1, Ahmed Ali2 & Ramzi Sabra1

1Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, American University of Beirut Faculty of Medicine, Beirut, Lebanon; 2Medical Education Unit, American University of Beirut Faculty of Medicine, Beirut, Lebanon

Abstract

Introduction: The forced transition to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted medical education significantly.

Methods: In this paper, the authors compare the performance of Year 1 and 2 classes of medical students who took the same courses either online (2019-2020) or face-to-face (2018-2019), and compare their evaluation of these courses. The authors also present results of three survey questions delivered to current Year 1 medical students on the perceived advantages and disadvantages of online learning and suggestions for improvement.

Results: Performance and evaluation scores of Year 1 and 2 classes was similar irrespective of the mode of delivery of the course in question. 30 current (2019-2020) Year 1 students responded to the survey questions with a response rate of 25.4%. Some of the cited disadvantages had to do with technical, infrastructural and faculty know-how and support. But the more challenging limitations had to do with the process of learning and what facilitates it, the students’ ability to self-regulate and to motivate themselves, the negative impact of isolation, loss of socialisation and interaction with peers and faculty, and the almost total lack of hands-on experiences.

Conclusion: Rapid transition to online learning did not affect student knowledge acquisition negatively. As such, the sudden shift to online education might not be a totally negative development and can be harnessed to drive a more progressive medical education agenda. These results are particularly important considering the several disadvantages that the students cited in relation to the online delivery of the courses.

Keywords: Online Learning, COVID-19 Pandemic, Medical Students

Practice Highlights

- The authors report on the forced transition to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The performance and evaluation scores were similar in online delivery vs face-to face.

- The sudden shift to online education might not be a totally negative development despite the several disadvantages that students cited.

I. INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted medical education significantly. Students were sent home and many schools were forced to shift their teaching, almost overnight, from face-to-face encounters to virtual, online delivery, in many cases without having had substantial previous experience with this mode of delivery. This disruption spanned the clinical and preclinical years. In previous events, researchers prioritised the synthesis of available evidence in terms of training medical students to respond and mitigate the effects of different types of disasters (Ashcroft et al., 2020). While there was more attention to find solutions for medical education in difficult settings (McKimm et al., 2019), including few examples that came to light after the outbreaks of H1N1 and H5N1 influenza, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Patil et al., 2003), and most recently, Ebola (Woodward & McLernon-Billows, 2018), there is paucity of literature that could inform adaptations of medical education methods during or post disasters, conflicts, or outbreaks. Recent articles have reflected on these changes and challenges and have suggested means of responding to the new reality, and offered advice on adopting new tools to ensure the best possible delivery of the curriculum (Daniel, 2020; Fawn et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; Ross, 2020; Sandars et al., 2020).

A recent meta-analysis that compared offline and online undergraduate medical education (under normal circumstances) revealed either no difference in outcomes on knowledge tests or a slightly higher performance for those who received online learning (Pei & Wu, 2019). In addition, a review of the literature showed that the adoption of E-Learning, in comparison with mostly traditional and other means of learning, expands access to education and increases the pool of faculty, in low resource settings (Frehywot et al., 2013). These data suggest that for preclinical education, there might not be a major negative impact of moving to online learning. It should be noted, however, that the situation brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated an abrupt transition to online education, may not be identical to that in which online delivery was a, planned and well-designed method to deliver at least part of the curriculum of the medical school; thus, the outcomes in knowledge acquisition during the recent COVID-19- forced transition to online teaching cannot be confidently predicted (Lim et al., 2009).

The American University of Beirut Faculty of Medicine (AUBFM), which follows the American model of medical education, suspended all in-person physical classes and assessments for years 1 and 2 on March 12, 2020. Thus, faculty, students and staff had to shift to online learning practically immediately. In this paper, we report our experience with this forced transition to online learning, specifically addressing Year 1 and 2 students’ perceptions of and response to it, and examining whether this transition affected their knowledge acquisition as reflected by their performance on written examinations.

II. METHODS

This is not a research study, as confirmed by our Institutional Review Board (IRB), since our purpose was to describe our experience with the delivery of the medical school curriculum after the sudden shift to online education, and whether that affected the students’ performance on their examinations and their evaluation of the courses. This was neither a planned intervention nor a systematic approach to test a specific hypothesis.

A. Setting

We analysed data from Year 1 and 2 classes of medical students who took the same courses either online (2019-2020) or face-to-face (2018-2019). We examined student performance in two courses, one for first year medical students (115 Class of 2022 students as face-to-face in 2018-2019 versus 118 Class of 2023 students as online in 2019-2020) entitled The Blood, and the other for second year medical students (114 Class of 2021 students as face-to-face in 2018-2019 versus 115 Class of 2022 students as online in 2019-2020) entitled Human Development and Psychopathology. Both courses are integrated modules that cover the histology, pathology, physiology, biochemistry, pathophysiology, pharmacology of the blood and lymphatic system and of neuropsychiatry, as well as the clinical, social, ethical, and behavioural aspects of related disorders.

Both courses extend over four weeks and end with a final summative examination. The main teaching activities consist of lectures and team-based learning (TBL) sessions, along with other small or large group discussions sessions dealing with epidemiology, evidence-based medicine, medical ethics, and social determinants of health relevant to the medical topics being covered.

The transition to online learning with the current medical students (2019-2020) was as follows: The didactic lectures were delivered either as asynchronous Voice-Over-PowerPoint (VOP) recordings or synchronous live lectures using Webex, which were recorded live. These recordings were made available to students on Moodle, the learning management system used at AUBFM. Faculty chose which of the two modes best suited them. As for the TBLs and group discussion sessions, they were run live using either Webex or Zoom applications. The latter was particularly appropriate for TBL sessions as it allowed virtual breakout rooms for team discussions.

The Respondus lockdown browser, with camera recordings serving as a virtual proctor, was adopted for written assessments, which included the individual Readiness Assurance Tests (i-RAT) of the TBLs as well as the final examinations. All these assessments utilise single-best answer multiple choice questions. Previous to the transition to online learning in 2018-2019, all i-RATs and group-RATs (g-RATs) were paper-based with physical proctoring, while the final course examinations, which used single best answer multiple choice questions, were computer-based, and were run on American University of Beirut (AUB) secure computers, also with physical proctoring.

Prior to COVID-19, final examinations were a hybrid of locally generated questions and National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) customised examinations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, NBME examinations were not available and final examinations were totally locally generated. With regard to TBL’s, during the online transition, no g-RATs were performed due to our inability to ensure their security; thus, automatic feedback, which was an integral part of the TBL process, was not possible, and was replaced by a brief review of the questions by the TBL preceptor.

In addition, and in order to reduce the potential for cheating and communication among students, we reduced the time allotted for final examinations from 1.2 minutes per question to 1 minute per question. Reducing the on-line time during examinations was also done in order to minimise connectivity problems that arise due to the poor internet infrastructure in Lebanon and due to the frequent cuts in electricity.

B. Students’ Attitudes

At AUBFM, at the end of every course, students are expected to anonymously fill an online course evaluation form. This form includes twelve statements on various aspects of the course with which the students express a level of agreement (Sup. Table 1). Scores are assigned to their responses as follows: 1: Strongly disagree, 2: Disagree, 3: Neither agree nor disagree, 4: Agree, 5: Strongly agree. One of the items on that form (# 4) addresses the effectiveness of the teaching methods. An overall course rating is calculated as the average score for all 12 items. We compared the scores on both item #4 and the overall rating for the course given online (2019-2020) for both Year 1 and 2 medical students with the scores for the same course when delivered face-to-face (2018-2019).

Due to the lack of survey items that are specifically tailored to online teaching in the regular course evaluation forms, we asked the students to respond to 3 additional open-ended questions. This part was administered only to the current (2019-2010) first year medical students who had completed the Blood course and were the following:

1) In your opinion, what are the advantages of online teaching and learning over face-to-face teaching and learning?

2) In your opinion, what are the disadvantages of online teaching and learning over face-to-face teaching and learning?

3) Please provide suggestions for improvement of the online teaching and learning process.

C. Performance on the Final Examinations

Overall performance in the same courses was compared between the current classes (online) and the previous year’s classes (face-to-face). Thus, for the current Year 1 class (Class of 2023) the comparator class was the current Year 2 class (Class of 2022), and for the latter the comparator class was the current Year 3 class (Class of 2021). We restricted the comparisons of final examination grades to performance of the various classes on the locally generated questions.

In order to ensure that any two classes being compared did not differ in terms of academic or cognitive abilities, we also compared the performance of the current and the previous year’s classes according to: 1) their scores on the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) taken prior to admission to medical school; and 2) their overall grades in other courses that were given face-to-face during the current year (i.e. in the earlier part of the 2019-2020 academic year); these courses included one entitled Cellular and Molecular Basis of Medicine (CMM) given during year 1, and another entitled The Kidney and Urinary System given during year 2; these were the first courses to be delivered during the current year.

In comparing grades and scores on courses and examinations, we took into account the passing standards set for each. At AUBFM, we use criterion based absolute passing grades for every assessment. For written assessments such as final examinations using multiple choice questions, the Angoff method is utilised to set the passing grade. Similarly, the passing grade for a course is calculated based on the weighting of the individual assessment tools in that course. Thus, for any two courses or examinations that we compared, we first did the analysis using the raw grades, and then, when needed, we also compared the adjusted grades after equalising the passing grades.

D. Data Analysis

For the three survey questions, answers were downloaded on excel for systematic and iterative thematic analysis. Answers were manually coded by one of the authors. The compiled codes were then discussed, compared and consolidated into themes by two of the authors over 3 meetings. The focus was on main themes, commonalities and conflicting views of participants, and relationships between themes. Findings were tabulated with relevant quotes. For the evaluation scores and performance on exam, data were available on excel and statistical comparisons were conducted using the Student’s unpaired t-test.

III. RESULTS

A. Students’ Attitudes

Twenty-six of the 118 current medicine one student filled the survey, and four more sent an email to the course coordinator, the response rate is hence 24.5%. Several themes emanated for each of the three questions especially concerning disadvantages of online learning; these are tabulated in Table 1 with representative quotes. The main advantages of online learning were the time flexibility with asynchronous learning coupled with better overall well-being as a result of staying at home. VOPs were valued because they allowed students to control their learning pace.

As for disadvantages, there were several. These included: the loss of motivation, the potential for procrastination, the problems arising from a bad internet connection leading to greater internet costs, inadequacy of the home environment for learning, less interaction with teachers and students, paucity of immediate feedback, loss of hands on experiences, and struggles because of the faculty’s deficiencies in the area of information technology in general, and in online teaching, in particular.

The students made several suggestions to improve the process, and these included proposals for faculty development, and provision of better technical support and knowhow. In addition, they proposed to decrease or cancel synchronous lectures and provide all didactic lectures as VOPs, to be followed by synchronous online sessions for questions and feedback. They also proposed to imbed questions within the VOPs to stimulate students to think (akin to audience response polls used in live lectures), as well as forum discussions to increase interactions with peers and faculty. Students also insisted that they receive more detailed feedback on their performance on examinations and i-RAT questions.

Despite the many disadvantages cited and the clear room for improvement for online teaching and learning, the overall course ratings as well as the evaluation of teaching for the online courses were not different from their face-to-face counterparts (Tables 2 and 3).

|

Survey question |

Theme |

Quote |

|

Advantages of online teaching and learning in comparison to face to face teaching and learning |

Time flexibility with asynchronous learning |

“Better scheduling that allows us to sleep and rest at night in order to wake up better prepared to ace those PowerPoints” (S9) “Easier to manage our time” (S18) |

|

Control of learning pace with VOP |

“Being able to speed through slides/concepts we already understood and pausing and replaying concepts that we have trouble with makes the whole learning process a lot more efficient and focused” (S27) |

|

|

More wellbeing |

“Less time to commute which allows more time to rest and take care of oneself” (S9) “Having a very healthy diet with my family in the village” (S12) “The [exam] performance is better and stress in minimal” (S23) |

|

|

Disadvantages of online teaching and learning in comparison to face to face teaching and learning |

Potential for procrastination and loss of motivation |

“Less motivation, harder to follow the schedule, requires strong time management skills” (S5) “Face to face teaching helps me organize my day better” (S4) “Being at university with other students around studying during the day motivated me” (S26) |

|

Bad internet connection |

“Internet connection in our country is not stable to hold a class or an exam, so we are resorting to 3g/4g. This leads to a lot of extra expense” (S3) “Time consuming” (S2) and “Sessions would run for more than their original allocated time” (S3) “Longer exams might coincide with the times of the electricity shut offs. This would automatically freeze Respondus and the student will have to restart their computer and so on. Although we are given extra time this adds a lot of stress to an already stressful situation” (S19) “Asking questions are much more difficult and needs much more time” (S7) “WebEx needed a stronger Wi-Fi in some sessions which leads to a harder way to grasp the information” (S18) “The internet connection everywhere in Lebanon is not the best, sometimes we have trouble listening. Sometimes it also gets really crowded when everyone wants to talk at the at the same” (S21) |

|

|

Home environment less conducive to learning |

“Not everybody has the privilege of adjusting their environments to their liking, whether that be because of their dog barking or their family members not respecting their study time” (S28) “This experience helped my appreciate how much I concentrate better in the library” (S9)

|

|

|

Loss of interaction with teachers |

“No direct interaction, harder to communicate directly with professors” (S2) “Face to face interaction was lost: no clues to non-verbal clues, no gestures seen” (S17) “It is true that we can always email the doctors for any additional questions but that does not compare to in person interactions” (S19)

|

|

|

Loss of interaction with students |

“not being able to interact with my friends” (S12) “Students lose their social skills as they interact less with each other-more into introversion” (S17) “You feel there is a barrier between you and the students” (S17) |

|

|

Lack of immediate feedback |

“One problem is during exams not being able to see my mistakes” (S15) “Not correcting our exam and not seeing our mistakes was a huge disadvantage for the online learning” (S18) “Restricting questions to only emails” (S11) and “some professors don’t respond to emails” (S16) and “the response may be delayed” (S29) |

|

|

Loss of hands on experiences |

“No hands-on experience for courses like clinical skills” (S3) “Mainly missing out on clinical skills” (S22) |

|

|

Faculty’s lack of IT knowhow or experience |

“Professors have different abilities and effectiveness in knowing how to do a VOP/online lecture” (S11) “Most Drs. don’t know how to use zoom or WebEx” (S6) “Many instructors are not technically inclined or are outright aversive to it” (S13) “So much time is wasted on technical issues” (S19) “Professors sometimes don’t see the raised hands and sometimes it doesn’t even work. In some lectures we had to wait for the professor to give us access, so we spent time waiting while they didn’t see that some people are trying to access the lecture” (S21) “One of the disadvantages is using the live WebEx sessions. Some professors are losing their recordings, others have a poor connection” (S23) |

|

|

Effect on faculty’s teaching skills |

“Some professors …just read instead of teaching” (S7) “Many professors are not exactly cooperative in terms of explaining mainly because they read their PowerPoints” (S23) “Can’t explain a topic and be passionate about it if talking to a screen or microphone” (S23) |

|

|

Suggestions to improve the current online teaching |

Technical support and knowhow |

“Train the staff on the proper way of utilising the platforms” (S2) “Make IT staff more readily available to help instructors” (S16) “Agree on one way to give the lecture via WebEx as some professors used WebEx team, where we had to ask permission for access, and it was kind of chaotic. It would also be better if the professor agreed on one way to have the questions asked to avoid interruptions and multiple people talking at the same time” (S21) |

|

More VOPs and less WebEx for lectures |

“I think VOP is a much safer option and a less tiring one” (S23) “Revert from live WebEx sessions to VOP” (S3) |

|

|

More interaction and immediate feedback |

“Open forums for discussion” (S3) “Adding analytical questions in PowerPoints” (S9) “See exams and mistakes” (S15) “If the professors want to use WebEx … then they should allow questions at all times and not only at the end of the session” (S11) “Include small assessment questions (clicker like questions) at the end of each major concept so that the students can assess their understanding” (S19) “Recording voice over PowerPoint for lectures, with every group of lectures followed by a WebEx session where the professor answers questions” (S24) “Review/Q&A session once a week” (S25) |

Table 1. Themes Generated from the Three Survey Questions with Selected Representative Quotes

VOP: Voice Over PowerPoint

|

Medicine class of |

2022 |

2023 |

P-value |

|

Academic Year 1 |

2018-2019 |

2019-2020 |

|

|

Number of students |

115 |

118 |

|

|

|

Baseline performance |

||

|

MCAT scores |

509±6 |

510±6 |

0.119 |

|

Class average on the final exam of the CMM course |

82.6±6.1 |

84.3±7.4 |

0.011 |

|

Passing grade for the final exam of the CMM course |

64.1 |

64.7 |

|

|

Adjusted grade for the final exam of the CMM coursea |

83.2±6.1 |

84.3±7.4 |

0.065 |

|

|

Performance in The Blood course |

||

|

Course delivery |

Face to Face |

Online |

|

|

Number of questions on the final exam |

50 |

77 |

|

|

Class average on the final exam |

83±9 |

81±9 |

0.043 |

|

Passing grade for the final exam |

65 |

61 |

|

|

Adjusted grade for the final exama |

83±9 |

85±9 |

0.091 |

|

|

Student Evaluation of The Blood Course |

||

|

Rating of teaching methods |

4.0±0.8 |

4.0±1.0 |

0.920 |

|

Overall course rating |

4.0±0.7 |

4.1±0.8 |

0.754 |

Table 2. Comparison of Performance of Year 1 Students in Various Courses and Examinations and Their Evaluation of the Blood Course

Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation

P-values were generated by Student’s unpaired t-test

MCAT: Medical College Admissions Test; CMM: Cellular and Molecular Basis of Medicine

aadjusted after equalizing the passing grades on the examinations in the 2 different years

|

Medicine class of |

2021 |

2022 |

P-value |

|

Academic Year 2 |

2018-2019 |

2019-2020 |

|

|

Number of students |

114 |

115 |

|

|

|

Baseline performance |

||

|

MCAT scores |

509±5 |

509±6 |

0.842 |

|

Class average on the final exam of the CMM course |

83.8±6.4 |

82.6±6.1 |

0.156 |

|

Passing grade for the final exam of the CMM course |

65.3 |

64.1 |

|

|

Adjusted grade for the final exam of the CMM coursea |

82.6±6.4 |

82.6±6.1 |

0.455 |

|

Performance on the final exam of The Kidney course |

78.1±7.9 |

78.7±7.2 |

0.558 |

|

Passing grade for the final exam of The Kidney course |

62.2 |

62.3 |

|

|

|

Performance in the Human Development and Psychopathology course |

||

|

Course delivery |

Face to Face |

Online |

|

|

Number of questions on the final exam |

45 |

75 |

|

|

Class average on the final exam |

83.7±7.4 |

83.5±6.8 |

0.892 |

|

Passing grade for the final exam |

68.0 |

64.8 |

|

|

Adjusted grade for the final exama |

83.7±7.4 |

86.7±6.8 |

0.002 |

|

|

Student evaluation of the Human Development and Psychopathology course |

||

|

Rating of teaching methods |

4.2±0.9 |

4.1±0.9 |

0.426 |

|

Overall course rating |

4.3±0.7 |

4.1±0.8 |

0.251 |

Table 3. Comparison of Performance of Year 2 Students in Various Courses and Examinations and Their Evaluation of the Human Development and Psychopathology Course

Data are presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation

P-values were generated by Student’s unpaired t-test

MCAT: Medical College Admissions Test; CMM: Cellular and Molecular Basis of Medicine

aadjusted after equalizing the passing grades on the examinations in the 2 different years

B. Performance of Students in the Courses and Examinations

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, there were no statistically significant differences in the MCAT scores between any two classes that were compared. The performance of the Year 1 students on the CMM course during the current academic year (online) was higher than that of students during the previous year (face-to-face); however, the passing grade for the two courses was slightly different. When the passing grades were equalised, there was no longer a difference between the two classes. Similarly, there was no difference in the performance of the Year 2 students on either the CMM course they took in Year 1, or on The Kidney and Urinary System course between the current class and the previous year’s class (all face-to-face).

With regard to The Blood course, the grade on the final examination was significantly lower for current students (online) relative to their predecessors (face-to-face); however, the passing grades on these examinations were different, with the current year’s examination having a lower passing grade than last year’s. When the passing grades were equalised, there was no longer a difference in the performance on the final examination.

The performance of the students in the Human Development and Psychopathology course’s final examination was almost identical in the online group compared with their predecessors (all face-to-face). Interestingly, the passing grade on this year’s examination was lower than that on last year’s examination, such that when the passing scores were equalized, the current class had better performance on the final examination than last year’s class.

IV. DISCUSSION

Medical education scholars have been increasingly disseminating opinions about sudden transitioning to online education to COVID-19 and the adaptations that are being implemented. Few studies have documented the actual institutional experiences, the perspectives of students, and the lessons learned in different medical courses or curricula such as TBL (Gaber et al., 2020), anatomy (Srinivasan, 2020) and continuing medical education in obstetrics and gynaecology (Kanneganti et al., 2020). Only one report from Wuhan, China, evaluated nursing interns’ outcomes on emergency medicine theoretical and practical examination scores (Zhou et al., 2020). The current paper is the first to examine the impact of this abrupt transition to online learning, which occurred in numerous countries worldwide, on the performance of our medical students in knowledge-based examinations. It reveals that the sudden shift to full online learning that our medical school had to adopt did not have a negative influence on the students’ knowledge acquisition as judged by their performance on final examinations. It also did not affect their overall reception and evaluation of the courses. These results are particularly interesting and important considering the many disadvantages that the students cited in relation to the online delivery of the courses.

Many of the limitations and disadvantages of online education cited by students had to do with technical and infrastructural matters and with faculty know-how and IT support. These are problems that can, theoretically, be easily remedied. The more challenging, however, limitations had to do with the process of learning, what facilitates or hampers it, the students’ ability to self-regulate and to motivate themselves, the negative impact of isolation, loss of socialisation and interaction with peers and faculty, and the almost total lack of hands-on experiences.

These limitations did not affect the students’ ability to achieve learning, at least in the domain of knowledge acquisition and application. It is clear that students in the three classes that were examined had, at baseline, a similar level of achievement meaning that any differences in student performance in the courses that were given online this year cannot be ascribed to differences in the academic performance or ability of the students. Therefore, the lack of difference in performance between classes taking the course online versus those taking it face-to-face suggests a consistency in performance that was not affected adversely by the sudden transition to online learning.

One reason for this lack of difference in performance between online and face-to-face delivery of the courses may be that the outcomes that were being sought and assessed were essentially knowledge acquisition and knowledge application. This agrees with the overall results of multiple studies that compared online vs offline learning in medical school, and which, in fact, tended to favour online learning (Pei & Wu, 2019). Indeed, even before our sudden shift to total online education, many of our students had adopted their own approaches to achieve the knowledge learning outcomes. Even though lectures were not available online, attendance at face-to-face lectures (which was not mandatory) was never complete, and for the majority of students, the rate of attendance ranged between 25% and 75% (unpublished data). In fact, the students indicated that they depended instead on notes and voice recordings made during the lecture that were shared by their classmates or predecessors, and that they used several Web-based resources. In contrast, attendance at TBL exercises and other interactive and small group sessions is mandatory at our school, and students uniformly participated in them, as they did in the online Zoom-based sessions. Thus, our students were probably well prepared for this sudden shift. In line with this view, Ferrel and Ryan (2020), in a recent editorial on the impact of COVID-19 on medical education, predicted that many medical students in their didactic years may perceive little change in their study schedule, since many of them already use outside resources and watch school lectures after they have been presented.

The lack of significant differences in scores and attitudes may also attest to our – and indeed all – medical students’ resilience and adaptability to difficult situations, for they are high-achieving and resourceful students who have been selected from among an exceedingly competitive group of applicants, and likely have the cognitive powers and non-cognitive qualities to meet such challenges. Ferrel and Ryan (2020) also emphasised the need for medical students to adapt and be innovative during the pandemic, and to devise ways by which they can exhibit their skills, work ethics and teamwork. In fact, one of the advantages of the online shift that our students cited was the flexibility this approach afforded them in managing their time, setting their schedules, controlling their pace of learning and achieving better self-care. Nevertheless, some of them found it challenging to do so, and to regulate their environment and motivate themselves; rather, they seemed to require external cues or assistance to get into a learning mode, and found difficulty in establishing boundaries between work and home, as suggested recently by Rose (2020). In this context, it is noteworthy that our students preferred asynchronous to synchronous learning, and this is consistent with Daniel’s recommendation to use this approach because it gives teachers “flexibility in preparing learning materials and enables students to juggle the demands of home and study” (Daniel, 2020).

Our findings also raise questions about certain assumptions regarding student learning and the optimal teaching approaches for knowledge-based objectives, such as the value and benefits of face-to-face interactions among students and with faculty in a didactic context. Our results suggest that students can achieve these knowledge objectives without the personal interaction and contact with faculty. This, of course, does not address the non-cognitive learning outcomes that might be negatively affected by pure online learning. As summarised by Fawn et al. (2020), while content may be covered well in such abrupt transitions to online learning, we cannot be sure that the valuable non-cognitive learning that happens as a result of the “social activity, the relationship-building, the problem-solving, the dialogue and generation of ideas and the students’ own discovery of other content that has not been pre-defined by the teacher” has been achieved.

We cannot make definite, long-term conclusions from this single account that is restricted to 2 courses in the preclinical years, a brief period of time, and one institution, and a low response rate for the survey questions, but the results are encouraging, and may have implications for educational practice. The lack of decline in cognitive performance may suggest that the sudden shift to online education might not be a totally negative development. If our findings are reproduced or generalised, one can use them to validate what progressive medical educators have been advocating for years, that: online educational technology must change the way we educate our students; didactic lecturing should give way to flipped classrooms; and valuable teacher time must be expended to help students apply knowledge rather than to simply transfer information in scheduled lectures. Quoting Ezekiel Emanuel (2020), who in a recent article stated that the reconfiguration of medical education, fuelled by online educational technology, seemed inevitable, Wolanskyj-Spinner (2020) suggested that the coronavirus epidemic appears to be an inflection point that is forcing a disruption in how we teach medicine. At AUBFM, we have long pressed the faculty who teach medical students to record their lectures and use the scheduled class time thus saved to implement flipped classrooms, employing small-group-based, problem-solving and interactive sessions. While many responded, many also hesitated, objected, and even resisted. The following two additional comments provided by two students illustrate their frustration with the resistance of faculty and their hopes to move in that direction:

“I really hope we can make online learning standard coming out of this phase … There was an attempt a few years ago but many instructors refused to be recorded or to fiddle with computers; we must seize the opportunity now.”

“Please never stop recording lectures, regardless of the status of live classes!”

Ahmed et al. (2020) recently reported that during the 2003 SARS epidemic in China, novel online problem-based learning techniques had to be implemented in one medical school that proved to be so popular that they were applied as part of the regular curriculum in later years. We believe that medical educators can harness the current disruption in how we teach medical students, and make use of to implement novel and sound educational practices and adopt a wide variety of valid approaches and tools that, otherwise, might have been resisted by unwilling individuals with entrenched ideas.

V. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, rapid transition to online learning did not affect student knowledge acquisition negatively. As such, the sudden shift to online education might not be a totally negative development and can be harnessed to drive a more progressive medical education agenda. These results are particularly important considering the several disadvantages that the students cited in relation to the online delivery of the courses.

Notes on Contributors

Nathalie Zgheib developed the concept, collected and analysed data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Ahmed Ali also developed the concept, performed the literature review, and revised the manuscript write-up. Ramzi Sabra also developed the concept, collected and analysed data, and revised the manuscript write-up. The three authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

This is a report of experience with educational practices. It was confirmed by our Institutional Review Board (IRB) that the activities described in this article do not constitute human subject research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank AUBFM faculty and medical students for their support, diligence and flexibility during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Declaration of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

References

Ahmed, H., Allaf, M., & Elghazaly, H. (2020). COVID-19 and medical education. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 777-778. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30226-7

Ashcroft, J., Byrne, M. H. V., Brennan, P. A., & Davies, R. J. (2020). Preparing medical students for a pandemic: A systematic review of student disaster training programmes. Postgraduate Medical Journal, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137906

Daniel, S. J. (2020). Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects, 49, 91-96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3

Emanuel, E. J. (2020). The inevitable reimagining of medical education. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(12), 1127-1128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1227

Fawn, T., Jones, D., & Aitken, G. (2020). Challenging assumptions about “moving online” in response to COVID-19, and some practical advice. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000083.1

Ferrel, M. N., & Ryan, J. J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus, 12(3), e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Frehywot, S., Vovides, Y., Talib, Z., Mikhail, N., Ross, H., Wohltjen, H., Koumare, A. K., & Scott, J. (2013). E-learning in medical education in resource constrained low- and middle-income countries. Human Resources for Health, 4(11), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-4

Gaber, D. A., Shehata, M. H., & Amin, H. A. A. (2020). Online team-based learning sessions as interactive methodologies during the pandemic. Medical Education, 54(7), 666-667. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14198

Kanneganti, A., Lim, K. M. X., Chan, G. M. F., Choo, S. N., Choolani, M., Ismail-Pratt, I., & Logan, S. J. S. (2020). Pedagogy in a pandemic – COVID-19 and virtual continuing medical education (vCME) in obstetrics and gynecology. Acta Obstetetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 99(6), 692-695. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13885

Liang, Z. C., Ooi, S. B. S., & Wang, W. (2020). Pandemics and their impact on medical training: Lessons from Singapore. Academic Medicine, 95(9), 1359-1361. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003441

Lim, E. C., Oh, V. M., Koh, D. R., & Seet, R. C. (2009). The challenges of “continuing medical education” in a pandemic era. Annals of Academic Medicine Singapore, 38(8), 724-726.

McKimm, J., Mclean, M., Gibbs, T., & Pawlowicz, E. (2019). Sharing stories about medical education in difficult circumstances: Conceptualizing issues, strategies, and solutions. Medical Teacher, 41(1), 83-90. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1442566

Patil, N. G., Chan, Y., & Yan, H. (2003). SARS and its effect on medical education in Hong Kong. Medical Education, 37(12), 1127-1128. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01723.x

Pei, L., & Wu, H. (2019). Does online learning work better than offline learning in undergraduate medical education? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical Education Online, 24(1), 1666538. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2019.1666538

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(21), 2131-2132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Ross, D. (2020). Creating a “quarantine curriculum” to enhance teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic Medicine, 95(8), 1125-1126.

Sandars, J., Correia, R., Dankbaar, M., de Jong, P., Sun Goh, P., Hege, I., Oh, S., Patel, R., Premkumar, K., Webb, A., & Pusic, M. (2020). Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

Srinivasan, D. K. (2020). Medical students’ perceptions and an Anatomy teacher’s personal experience using an e-learning platform for tutorials during the Covid-19 crisis. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 318-319. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1970

Wolanskyj-Spinner, A. (2020). COVID-19: The global disrupter of medical education. ASH Clinical News, https://www.ashclinicalnews.org/viewpoints/editors-corner/covid-19-global-disrupter-medical-education/

Woodward, A., & McLernon-Billows, D. (2018). Undergraduate medical education in Sierra Leone: A qualitative study of the student experience. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1397-6

Zhou, T., Huang, S., Cheng, J., & Xiao, Y. (2020). The distance teaching practice of combined mode of massive open online course micro-video for interns in emergency department during the COVID-19 epidemic period. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 26(5), 584-588. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0079