Remote physiology practical: Viable alternative to in-person practical in health sciences education?

Submitted: 7 December 2021

Accepted: 8 February 2022

Published online: 5 April, TAPS 2022, 7(2), 27-36

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-2/OA2718

Tan Charmaine1 & Ivan Cherh Chiet Low1,2

1Department of Physiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 2Human Potential Translational Research Programme, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Practicals are core components of an undergraduate health sciences curriculum to promote experiential learning and motivation in students. With restrictions on traditional forms of face-to-face practicals during the COVID-19 pandemic, we designed and investigated the efficacy of remote practicals as a viable learning strategy in exercise physiology teaching.

Methods: Student volunteers were instructed to perform a graded exercise test in a remote setting and provide their collected data for subsequent discussion in an online lecture. The effectiveness of this remote practical in promoting students’ motivation and learning outcomes achievement was assessed via an anonymous questionnaire containing 29 closed-ended and 2 open-ended items. Continual Assessment (CA) results were also investigated. Unpaired student’s t-tests were performed for comparisons between interventions with significance level set at P<0.05.

Results: Sixty-one (out of 81; 75%) students responded to the questionnaires and 49 (60%) consented to the use of their CA results for this study. Results revealed that students were moderately motivated and attained strong achievement of learning outcomes. When compared to students who did not volunteer for the hands-on component of the remote practical, students who participated in the hands-on component reported significantly higher self-efficacy (P<0.05) in explaining the practical procedures to their peers. Qualitative analysis further revealed that experiential learning and real-life data analysis were the central reasons supporting the effectiveness of the remote practical. Students were generally satisfied and would recommend the remote practical to future students.

Conclusion: Our study highlights the potential of remote practicals as viable alternatives to traditional practicals.

Keywords: Remote Practical, Experiential Learning, Student Motivation, Learning Outcomes

Practice Highlights

- Remote practical aids in promoting experiential learning in exercise physiology teaching.

- Remote practical can promote motivation by enabling students to see the relevance of their learning.

- Students perceived that they could achieve the necessary learning outcomes via remote practicals.

I. INTRODUCTION

Laboratory work or practical classes are considered as core components of health sciences curriculum in higher education (Colthorpe & Ainscough, 2021; Dohn et al., 2016; Hofstein & Lunetta, 2004). Past studies have revealed the strong educational value of practical classes in promoting student motivation (Bruce, 1988; Dohn et al., 2016), student learning outcomes achievement (Brinson, 2015) as well as the ability to draw theory to practical applications (Neves et al., 2017).

One of the key subjects in undergraduate health sciences education is human physiology, a discipline seeking to understand the underlying mechanisms and dynamics of the human body (Lellis-Santos & Abdulkader, 2020). The role of practical classes in the teaching and learning of physiology is highly valued by educators and students alike (Dohn et al., 2016; Neves et al., 2017). Experiential learning in physiology practicals commonly takes the form of interactive hands-on activities, real-time data collection and analysis of physiological responses. When such practicals are carried out in a traditional face-to-face manner, students are able to utilise laboratory equipment in an authentic experimental setting and generate real-time data from their peers and/or themselves (Colthorpe & Ainscough, 2021). Data analysis and discussion following the hands-on component of practicals can further promote contextualised learning and facilitate the understanding of the theoretical content (Lewis & Williams, 1994). It has been reported that such an interactive learning approach in physiology enhances the achievement of learning outcomes and increases the level of motivation for students (Dohn et al., 2016).

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to increasing safety management restrictions being imposed on physical classes in higher education institutes around the world (Ali, 2020). As such, educators were faced with the sudden need to switch from face-to-face lessons to online and remote teaching (Ali, 2020; Lellis-Santos & Abdulkader, 2020). Amidst the uncertainty of this transition, traditional face-to-face practicals have seen a sharp decline (Ray & Srivastava, 2020; Vasiliadou, 2020). As we examine these educational trends during crises, it becomes apparent that harnessing creativity to adapt and invent novel solutions is vital to maintain and even advance current standards of teaching and learning. Lellis-Santos and Abdulkader (2020) rightfully exemplify this notion by proposing the use of smartphone applications as a creative teaching approach to enable scientific data collection and practical learning from home even during social isolation. Along similar lines, we have designed a remote practical for students to carry out hands-on experiments outside of a traditional laboratory environment as an innovative alternative to circumvent the restrictions on face-to-face practicals and to provide them with experiential learning opportunities on cardiovascular concepts in exercise physiology.

To the best of our knowledge, there are few studies conducted to date regarding the efficacy of such remote practicals, particularly in the field of life sciences and exercise physiology. Therefore, our study aims to address this research gap by evaluating the effectiveness of our remote exercise physiology practical on (1) student learning outcomes, (2) student motivation and (3) students’ perceptions on the effectiveness and relevance of the remote practical. In addition, we also compared the quantitative and qualitative responses between students who participated and did not participate in the hands-on component of the remote practical. The Continual Assessment (CA) results from these two groups of students were also compared to assess if differences in academic performance existed between the two groups.

II. METHODS

A. Description of the Module

LSM3212 Human Physiology: Cardiopulmonary System is a third-year module in Life Sciences conducted by the Department of Physiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore. A total of 81 undergraduate Life Sciences students were enrolled in the module in the Academic Year 2020/2021, Semester 2. Traditionally, both lectures and practicals are carried out in a face-to-face manner for this module. However, due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons were forced to go online. As a result, a remote practical was designed and conducted as an innovative alternative for this batch of students.

B. Description of the Remote Practical

The remote practical was designed to provide students with experiential learning on cardiovascular concepts in exercise physiology. Conventionally, the practical involved a treadmill-based graded exercise test performed by a student volunteer equipped with specialised electrocardiogram-based heart rate monitors to illustrate how the cardiovascular system changes with increasing exercise stress. For the remote practical, however, students were given a set of practical handouts comprising a novel graded exercise protocol developed by the authors and could choose to perform it in their own time asynchronously, or not carry it out at all. In the graded exercise protocol, students were instructed to carry out a series of graded knee raise exercises and record their heart rate measured via a smartphone application together with other subjective exercise prescription ratings (ratings of perceived exertion and talk test ratings) after each set of exercise. The graded exercise protocol was developed with the intent to encourage contextualised learning from the practical content to real-life exercise routines. The consolidated data was subsequently used for discussion in a virtual lecture to illustrate how heart rate responses and cardiovascular adaptations may differ across individuals, as well as how the consolidated data may serve to guide exercise prescription. Participation in the hands-on component (knee raise exercises) of the remote practical was optional. However, participation in the analysis and discussion of the collated data in the virtual lecture conducted after the graded exercise was made compulsory. Via this design, the remote practical (comprising both the graded exercise and post-exercise discussion) not only replicated the pedagogy of the original in-class practical, but also augmented the opportunity for students to volunteer and take part in the graded exercise component of the practical.

C. Instruments

After the virtual lecture, students completed an anonymous (no informed consent required) questionnaire containing 29 closed-ended and 2 open-ended items. The purpose of this self-report questionnaire was to evaluate students’ perceived effectiveness of the remote practical on their motivation and achievement of learning outcomes of the virtual lecture.

Student motivation was measured by the Lab Motivation Scale (Dohn et al., 2016) containing 21 closed-ended statements based on three aspects – student interest, effort and self-efficacy. Multiple instruments had previously been employed to assess dimensionality and reliability of the validated Lab Motivation Scale (Dohn et al., 2016). A set of six closed-ended items were employed to measure students’ perception on whether they had achieved the intended learning outcomes of the remote practical. Lastly, two closed-ended items were included to elicit a general satisfaction score from students regarding the remote practical and/or the virtual lecture. All the closed-ended statements in the questionnaire were scored on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree).

Furthermore, there were two open-ended questions focusing on the effectiveness of the remote practical and the relevance of the remote practical to students’ daily lives. The first question was posed to uncover specific reasons supporting the analysis of the closed-ended items, while the second question aimed to encourage contextualisation of concepts learnt through the remote practical in students’ daily lives.

Finally, the CA results of students who participated in the hands-on component of the remote practical were compared with students who did not participate. To ensure a fair comparison, we took into consideration only the CA result from the questions corresponding to the content covered in the remote practical and virtual lecture. The questions taken into consideration made up 40% of the entire examination score.

D. Analysis

A mixed method approach was employed in analysing the questionnaire responses. An initial 66 questionnaire responses were collected but five incomplete responses were excluded, leaving a total of 61 responses that were included in the final analysis. Responses to the closed-ended items were coded accordingly to a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1). Scores were reversed for statements phrased in a negative manner (items 9, 15 and 18). All closed-ended responses were presented in the form of mean ± standard deviation. As a measure of internal consistency, Cronbach’s α was used as an instrument and measured across all scales. Unpaired student’s t-tests were carried out to find out if differences between students who participated and did not participate in the hands-on exercise component were significant with significance level set at P < 0.05. All data analysis and statistical tests were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016.

Open-ended responses were analysed in a 3-part process: informal reviewing, open coding and thematic analysis. Firstly, all responses were informally reviewed to familiarise with general ideas and main themes were identified. Next, open coding was performed where each response was analysed in detail and coded to the most appropriate theme (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Finally, thematic analysis was carried out through ranking themes according to frequency and analysing the results (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The open-ended questions were made optional, and all responses collected were subsequently analysed.

III. RESULTS

Out of the 61 participants, 29 (48%) participated in the hands-on exercise component of the remote practical while 32 (52%) did not participate. Both groups attended the compulsory virtual lecture conducted after the remote practical, where the data collected from the remote practical was consolidated and discussed with the entire class.

Internal consistency was calculated using Cronbach’s α and the reliability coefficient was found to be 0.95 across all closed-ended items, indicating an excellent level of interrelatedness across the overall scale (Cronbach, 1951). Individual scales of learning outcomes and motivation were also subjected to the analyses of Cronbach’s α. The alpha coefficient value was calculated to be 0.86 for perceived achievement of learning outcomes and 0.94 for motivation (Tables 1 & 2). Motivation was further divided into three individual subscales assessing student interest, effort and self-efficacy, with the reliability coefficients returning 0.85, 0.88 and 0.88 respectively (Table 1). These reliability coefficients correlate strongly with those of Dohn et al. (2016), hence providing support for the internal consistency of the Lab Motivation Scale. Data supporting these findings is openly available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9. figshare. 17170 964 (Low, 2021).

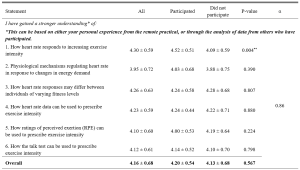

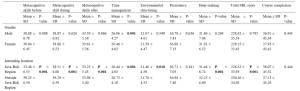

A. Remote Practical and Learning Outcomes

In general, students rated between “Agree” and “Strongly Agree” for perceived achievement of learning outcomes, with an overall mean score of 4.16 ± 0.68 on a 5-point Likert scale (Table 1). Students who participated in the hands-on component reported a mean score of 4.20 ± 0.54, which was similar to that rated by students who did not participate in the hands-on component (4.13 ± 0.68, P = 0.567; Table 1). For the first closed-ended statement: I have gained a stronger understanding of how heart rate responds to increasing exercise intensity, students who participated indicated a higher mean score of 4.52 ± 0.51 as compared to the lower mean score of 4.09 ± 0.59 (P = 0.004) for students who did not participate in the hands-on exercise component (Table 1).

Table 1. Students’ perceived achievement of learning outcomes in cardiovascular physiology

n = 61. Responses were coded from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). All means are shown with ±SD of the mean. **P < 0.01.

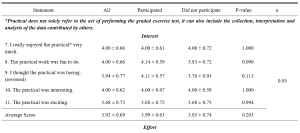

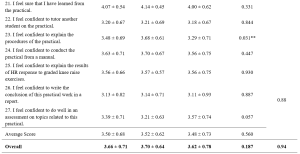

B. Remote Practical and Student Motivation

Students generally rated between “Agree” and “Somewhat Agree/Somewhat Disagree” for student motivation, with an overall mean score of 3.66 ± 0.71 (Table 2). Students who participated in the hands-on component reported a mean score of 3.70 ± 0.64, which was similar to that rated by students who did not participate in the hands-on component (3.62 ± 0.78, P = 0.187; Table 2). Students rated between “Agree” and “Somewhat Agree/Somewhat Disagree” regarding the three aspects of student motivation, with a score of 3.92 ± 0.69 for interest, 3.66 ± 0.75 for effort and 3.50 ± 0.68 for self-efficacy respectively (Table 2). For statement 23, students who participated indicated a higher mean score of 3.68 ± 0.61 as compared to the lower mean score of 3.29 ± 0.71 (P = 0.031) for students who did not participate in the hands-on component (Table 2).

Table 2. Students’ perceived motivation towards the remote practical

n = 61. Adapted from the Lab Motivation Scale (Dohn et al., 2016). Responses were coded from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Scores were reversed for statements phrased in a negative manner. All means are shown with ± SD of the mean. **P < 0.05.

C. Qualitative Explanations on Perceived Effectiveness and Relevance of Remote Practical

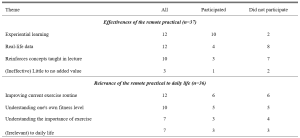

The first open-ended item sought to investigate the reasons underlying the perceived effectiveness or ineffectiveness of the remote practical in enhancing students’ learning. Of the 37 responses, 34 (92%) felt that the remote practical was effective while 3 (8%) felt it was ineffective and of little to no added value to them (Table 3). Experiential learning and real-life data emerged as the most common themes cited across all responses (n = 12), followed by reinforc(ing) concepts taught in lecture (n = 10; Table 3). Experiential learning was reflected as the most common response among students who participated in the hands-on component (n = 10) in comparison to real-life data indicated by students who did not participate in the hands-on component (n = 8; Table 3).

The aim of the second open-ended item was to investigate the relevance and application of the remote practical to students’ daily lives. Of the 36 responses, 29 (81%) felt the remote practical was relevant while 7 (19%) felt that it was irrelevant to their daily lives (Table 3). Overall, the remote practical was found to be most relevant in improving current exercise routine (n = 12), followed by understanding one’s own fitness level (n = 10) and understanding the importance of exercise (n = 7; Table 3). This trend was similar for both students who participated and did not participate in the hands-on component of the remote practical (Table 3).

Table 3. Themes identified from the open-ended responses, ranked by frequency

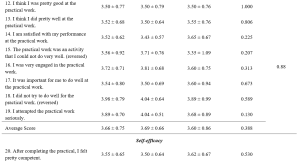

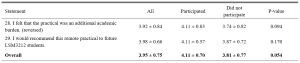

D. Remote Practical and Satisfaction Score

Students rated close to “Agree” for satisfaction, with an overall mean score of 3.95 ± 0.75 (Table 4). Those who participated in the hands-on component reported a mean score of 4.11 ± 0.70, which was similar to that rated by students who did not participate in the hands-on component (3.81 ± 0.77, P = 0.054; Table 4).

Table 4. Students’ satisfaction score

n = 61. Responses were coded from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). All means are shown with ± SD of the mean. **P < 0.05.

E. Remote Practical and Academic Performance

Out of the 49 students who consented to the use of their CA results for this research study, 30 (61%) participated in the hands-on component of the remote practical while 19 (39%) did not (Table 5). Only the questions corresponding to the content covered in the remote practical and relevant virtual lecture were taken into consideration for this study. The overall mean mark was 7.3 ± 1.64 out of 10 (Table 5). Students who participated in the hands-on component (7.3 ± 1.84) and did not participate in the hands-on component (7.3 ± 1.32) exhibited similar mean marks as well (P = 0.940; Table 5).

Table 5. Students’ CA results

n = 49. CA scores are shown as mean ± SD, with *P < 0.05 considered significant.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study sought to evaluate if remote physiology practicals could be viable alternatives to traditional face-to-face practicals, especially during emergency remote teaching in a pandemic. Our results demonstrated that the students who participated in the remote practical perceived that they could achieve the learning outcomes in cardiovascular and exercise physiology teaching with reasonable satisfaction, regardless of whether they participated in the hands-on component of the remote practical. However, students who had actively participated in the hands-on component (graded exercise) reported that the remote practical had particularly benefitted them in better achieving certain learning outcomes as compared to their classmates who did not participate in the graded exercise. Specifically, students indicated that their participation in the graded exercise allowed them to have a better grasp of the concepts concerning heart rate response to increasing exercise intensity. This finding was not unexpected as the remote graded exercise was specifically designed to provide experiential learning opportunities to better comprehend the concepts underlying this particular learning outcome.

Perceived scores for the achievement of learning outcomes were otherwise similar between the participated and non-participated group. This could be attributed to the fact that the remote practical was used as a complement to the virtual lecture, wherein the interpretation and analysis of data collected from the optional graded exercise was discussed with the whole class during the compulsory virtual lecture. The perception scores of learning outcome achievement were well supported by the students’ academic performance as all of them shared similar mean CA marks regardless of their participation in the remote practical. This similarity is especially prominent as the CA questions were set based on the principle of constructive alignment (Biggs, 1996; Bloom, 1956; Stamov Roßnagel et al., 2020).

Interestingly, open-ended responses revealed “experiential learning” as the key reason supporting the efficacy of the remote practical in students who participated in the graded exercise while “having real-life data which reinforces concepts taught in lecture” were key reasons indicated by students who did not participate in the hands-on component of the remote practical. These findings are in line with studies recommending experiential learning as one of the seven “principles of good practice” to achieve excellence in higher education (Chickering & Gamson, 2006). This is accomplished by generating real-life data to allow students to draw the link between theoretical content and practical applications, before applying it to analyse real-life situations in view of course material (Lewis & Williams, 1994). This suggests that the remote practical is able to foster environments which could encourage hands-on learning and real-time data generation to enhance student learning, even if not conducted in a traditional laboratory setting.

Overall, students were satisfied with the remote practical and/or virtual lecture, with those who participated in the hands-on component generally being more satisfied. Even though the remote practical was not compulsory, those who took part in the hands-on component generally did not view it as an additional academic burden and instead would recommend it to future batches of students. This reinforces the potential of such remote practicals in helping students to achieve learning outcomes without imposing unnecessary pressure on them.

With motivation being a strong indicator of self-directed learning and academic achievement (Cortright et al., 2013), it is crucial for educators to assess and understand the importance of motivating students. In fact, educators play a critical role in determining the motivation levels of their students through the nature of their classes and assignments (Cortright et al., 2013). Specifically, Dohn et al. (2016) states that students’ motivation could be negatively impacted by limited equipment or restricted time for practicals. Majority of students face similar limitations for a graded exercise test carried out in a traditional face-to-face practical. Typically, only one volunteer would carry out the actual exercise experimental protocol due to equipment and time constraints, while other students would passively watch and learn from the data collected. The novel remote practical proposed in this study could potentially overcome these limitations as students are able to personally experience the hands-on exercise component within their own spaces at home and at their own convenience, thereby possibly enhancing their motivation levels.

Our results indicated that overall motivation towards the remote practical and/or the virtual lecture ranged from 3 to 5, corresponding to “somewhat agree” and “strongly agree”, with a mean value of 3.62 ± 0.78. This is comparable to the motivation scores previously reported by Dohn et al. (2016) for in-class biomedical laboratory classes. The positive motivation score could be explained by the fact that majority of students (81%) could see the relevance (Table 3) of the remote practical in their daily lives. Learning activities which guide students towards finding ‘personal meaning and value’ in the educational content is known to positively influence their motivation levels (Cortright et al., 2013). By providing opportunities for students to reflect on, find meaning and draw relevance to their personal lives, such remote practicals can potentially address common limitations of traditional practicals and boost student motivation and learning.

Delving further into the three aspects of student motivation – interest, effort and self-efficacy, students rated the highest scores for interest, followed by effort and lastly self-efficacy. The score for effort placed into the practical could have been understandably affected due to the non-compulsory nature of the graded exercise. The exercise component of the practical could not be made compulsory as not all students were medically/physically fit enough to undergo a graded exercise test. Nonetheless, the similarity in perceived learning outcomes and academic results between students who did and did not participate in the graded exercise suggests that the follow up analysis and peer-based discussion of the tabulated data involving the entire class was sufficient to bridge the learning gap between the two groups of students. Overall, the favourable perceived learning outcomes (ranging from “agree” to “strongly agree”) and academic scores (corresponding to a grade of “A-” to “A”) reinforces the value of the remote practical as a teaching strategy to promote learning in exercise physiology, regardless of the students’ ability or interest to participate in strenuous physical activity. However, whether the remote practical is more effective than a conventional face-to-face practical or no practical at all remains an interesting question which necessitates future research as this cannot be addressed given the limitations of our current study design.

Notably, self-efficacy scores were rated the lowest amongst the three aspects of motivation. This could be due to the fact that students are not closely supervised during a remote practical, unlike face-to-face practicals. Without the physical presence and continuous guidance of an instructor, students could have faced uncertainty as to whether instructions were properly executed. Thus, strategies to enhance pre-practical instructions using asynchronous video instructions or the incorporation of remote supervision methods may aid to further enhance the effectiveness of the remote practical. Interestingly, participation in the hands-on component of the remote practical appeared to have nonetheless enhanced the confidence of students in explaining the procedures of the practical to their peers (Table 2). This finding is of particular importance, as the ability to teach and explain is an indication of higher order learning corresponding to the second and third levels of the Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom, 1956).

A. Limitations

Our study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a remote exercise physiology practical in promoting student motivation and learning in a cohort of Life Sciences undergraduates. However, the current study design does not permit immediate comparison with conventional face-to-face practicals as students could not be randomly allocated into different comparison groups (remote or face-to-face) owing to pandemic restrictions and ethical reasons. Also, we could only investigate the effects of practical participation on the effectiveness of the remote practical in enhancing student motivation and learning outcomes achievement using a quasi-experimental approach. This is so, for we were unable to randomly allocate students into two comparison groups given that not all students were medically/physically fit enough to undergo a graded exercise test for the hands-on component of the remote practical. Based on this study design, some degree of self-selection bias could have been present as physically active students who had volunteered to take part in the exercise component of the remote practical could have seen greater relevance to their daily lives and could have been more intrinsically motivated to partake and learn from the practical session. In spite of that, the overall student motivation score appeared comparable between the two groups of students who participated and did not participate in the exercise component of the practical, suggesting that the degree of self-selection bias may not be of significant concern in the present study.

V. CONCLUSION

Overall, students reported that experiential learning and real-life data were the main reasons supporting the effectiveness of the remote practical. With experiential learning and real-life data as key components of traditional practicals (Dohn et al., 2016; Randall & Burkholder, 1990), the present study demonstrates the potential of remote practicals as viable and innovative alternatives for face-to-face practicals in exercise physiology teaching. In cases of sudden shifts to emergency remote education, such alternatives offer the possibility of incorporating experiential learning even during social isolation.

Notes on Contributors

Tan conducted the study, analysed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. I.C.C. Low was involved in experimental conception and design, as well as critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

All students were provided with a participant information sheet containing the purpose and details of the research study. The questionnaire was made completely anonymous. Informed consent was obtained from students for use of their CA results only after the release and confirmation of their results. Circulation of research materials was done virtually and students were never approached directly for recruitment. The study was approved by the National University of Singapore – Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB) with study code NUS-IRB-2020-631.

Data Availability

Data supporting these findings is openly available via Figshare at DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 17170964.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the study participants who have spent their time and effort to complete the questionnaires and have provided consent in the use of their results for research purposes.

Funding

There was no funding support accorded for this study.

Declaration of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Studies, 10(3), 16-25. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32(3), 347-364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138871

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. David McKay.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brinson, J. R. (2015). Learning outcome achievement in non-traditional (virtual and remote) versus traditional (hands-on) laboratories: A review of the empirical research. Computers & Education, 87, 218-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.07.003

Bruce, R. H. (1988). Enhancing student motivation and learning: Experiences with a simple simulation. Higher Education Research & Development, 7(2), 103-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436880070201

Chickering, A., & Gamson, Z. (2006). Seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1991, 63-69. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.37219914708

Colthorpe, K., & Ainscough, L. (2021). Do-it-yourself physiology labs: Can hands-on laboratory classes be effectively replicated online? Advances in Physiology Education, 45(1), 95-102. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00205.2020

Cortright, R. N., Lujan, H. L., Blumberg, A. J., Cox, J. H., & DiCarlo, S. E. (2013). Higher levels of intrinsic motivation are related to higher levels of class performance for male but not female students. Advances in Physiology Education, 37(3), 227-232. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00018.2013

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Dohn, N. B., Fago, A., Overgaard, J., Madsen, P. T., & Malte, H. (2016). Students’ motivation toward laboratory work in physiology teaching. Advances in Physiology Education, 40(3), 313-318. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00029.2016

Hofstein, A., & Lunetta, V. N. (2004). The laboratory in science education: Foundations for the twenty‐first century. Science education, 88(1), 28-54. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10106

Lellis-Santos, C., & Abdulkader, F. (2020). Smartphone-assisted experimentation as a didactic strategy to maintain practical lessons in remote education: Alternatives for physiology education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Advances in Physiology Education, 44(4), 579-586. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00066.2020

Lewis, L. H., & Williams, C. J. (1994). Experiential learning: Past and present. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1994(62), 5-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.36719946203

Low, I. C. C. (2021). Remote physiology practical: Viable alternative to in-person practical in health sciences education? [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17170964

Neves, B. S., Altermann, C., Goncalves, R., Lara, M. V., & Mello-Carpes, P. B. (2017). Home-based vs. laboratory-based practical activities in the learning of human physiology: The perception of students. Advances in Physiology Education, 41(1), 89-93. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00018.2016

Randall, W. C., & Burkholder, T. (1990). Hands-on laboratory experience in teaching-learning physiology. Advances in Physiology Education, 259(6), S4-S7. https://doi.org/10.1152/advances.1990.259.6.s4

Ray, S., & Srivastava, S. (2020). Virtualization of science education: A lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of proteins and proteomics, 11, 77-80. https://doi.org/10.1007%2Fs42485-020-00038-7

Stamov Roßnagel, C., Fitzallen, N., & Lo Baido, K. (2020). Constructive alignment and the learning experience: Relationships with student motivation and perceived learning demands. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(4), 838-851. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1787956

Vasiliadou, R. (2020). Virtual laboratories during coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 48(5), 482-483. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21407

*Ivan Cherh Chiet LOW

Department of Physiology,

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

Block MD9, 2 Medical Drive Level 4

Singapore 117593

Email: phsilcc@nus.edu.sg

Submitted: 6 April 2021

Accepted: 2 December 2021

Published online: 5 April, TAPS 2022, 7(2), 17-26

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-2/OA2510

Nicola Ngiam1,2, Kristy X Fu1,3 & Jacqueline SM Ong1,3

1Khoo Teck Puat- National University Children’s Medical Institute, National University Health System, Singapore; 2Centre for Healthcare Simulation, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 3Department of Paediatrics, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

Abstract

Introduction: Personal protection in aerosol-generating procedures is an important skill to safely deliver care to patients in the COVID-19 pandemic. This aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of “just-in-time” simulation training for airway management in a suspected COVID-19 patient.

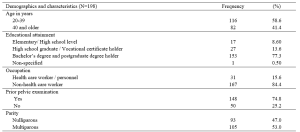

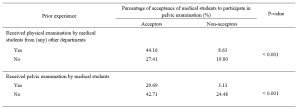

Methods: This was a prospective mixed-method cohort study in a tertiary paediatric department. A mandatory “just-in-time” simulation training session for intubation of a suspected COVID-19 patient was conducted. Pre- and post-simulation questionnaires were administered. Participants were invited to attend focus group interviews to further delineate their experience. Quantitative and qualitative methods were employed to analyse the data.

Results: Thirty-three participants, including doctors, nurses and respiratory therapists attended the training. Self-confidence in intubation, managing and leading a resuscitation team and dealing with problems with intubation significantly improved. Simulation was valued for the experiential learning as well as for increasing confidence and awareness. Process improvement suggestions from both participants and trainers were raised. There was a small signal of skill translation to real life scenarios.

Conclusion: Simulation-based training is a useful tool for infectious disease outbreak preparedness. Further research will need to be done to determine the impact on actual clinical practice in pandemics.

Keywords: Simulation, COVID-19, Pandemic Preparedness, Training, Intubation

Practice Highlights

- The authors report their experience with “just-in-time” in situ simulation training for emergency preparedness in the face of an infectious disease outbreak.

- Simulation training was well received and improved the confidence as well as awareness of frontline staff in managing intubation and resuscitation in a suspected COVID-19 paediatric patient.

- Process improvement suggestions from participants and trainers was a useful by-product of the simulation training activity.

I. INTRODUCTION

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak a public health emergency of international concern on 30 January 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic has now affected millions of people worldwide, with a wide range of case fatality rates amongst the 210 countries and territories affected (The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences University of Oxford, 2020). In Wuhan, China, one of the first epicentres of this international pandemic, out of 44672 confirmed cases of COVID-19, 1716 were healthcare workers (HCWs) (Wu & McGoogan, 2020). Of the confirmed cases among HCWs, 14.6% were classified as severe or critical, and 5 deaths were observed (The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team, 2020). Early reports suggest that modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 include droplet and contact (via the fecal-oral route and fomites); airborne transmission may occur during aerosol-generating procedures (World Health Organization, 2020).

During the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak, despite the presence of existing safety protocols, up to half of the SARS-CoV cases in some centers were HCWs as a result of transmission within hospital units (Booth et al., 2003). Critical care and emergency care providers are often involved in high-risk aerosol-generating procedures such as oronasal suctioning, bag-valve-mask ventilation, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, and endotracheal intubation in patients with COVID-19 with respiratory failure, and so must be prepared (Caputo et al., 2006; Wax & Christian, 2020; Zuo et al., 2020). The challenge for providers would be to provide high-quality and timely care to infected patients, without compromising their own safety. Apart from having adequate supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE), a safe environment for HCWs requires the provision of up-to-date information regarding the disease, smooth dissemination of protocols, and easy accessibility to portals reinforcing education and training in infection control procedures. Lau et al. (2004) reported that HCWs who underwent more than 2 hours of training were far less likely to be infected with SARS-CoV during the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak in Hong Kong. In addition to PPE training, we felt that a simulated airway management scenario in a suspected COVID-19 patient was a vital component of training in order for staff to experience the profound challenges of performing high risk aerosol-generating procedures while in PPE and in isolation facilities. During the recent 2014 to 2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak, Grillet et al. (2015) with the use of simulation, found that commonly performed procedures in the intensive care unit becomes more complicated, more stressful and less comfortable in appropriate PPE. We were fortunate to find a window of opportunity close to the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore to prepare our healthcare teams using “just-in-time” in-situ simulation. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of this training on our resuscitation teams when managing a respiratory emergency of a suspected COVID-19 pediatric patient.

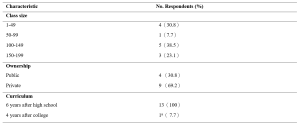

II. METHODS

This was a prospective mixed-method cohort study in a paediatric department of a tertiary university hospital. Residents were put through a mandatory “just-in-time” simulation training session to prepare them for intubation of a suspected COVID-19 patient. The doctors involved were senior paediatric residents who regularly manage emergencies on call. Nurses and respiratory therapists were rostered to participate whenever available on shift. Participants worked in teams of 5 to 6 to manage a simulation scenario involving a patient with bronchiolitis who was suspected to have COVID-19. Each team comprised of participants from each of the healthcare professional groups listed above. Actual personal protective equipment (PPE) including powered air-purifying respirators (PAPR) were used in the simulation. Participants received training in the use of PPE and PAPR prior to the simulation session. The simulation was conducted in-situ in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) using a SimBaby (Laerdal). The scenario used can be found in the appendix. Each group participated in one scenario. Each scenario lasted 30 to 40 minutes. The end point was successful intubation of the patient. There were 2 instructors (paediatric intensive care clinicians) present, one in the anteroom and one in the patient’s room. Debriefing was conducted as a group by both instructors immediately after every simulation. Each debriefing session lasted 30 to 45 minutes and focused on technical and non-technical skills.

Anonymous pre-simulation and post-simulation questionnaires were administered. Questions focused on confidence levels with managing intubation in a COVID-19 suspect patient, using the PAPR, and anxiety levels. Responses were rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 5. Quantitative data was analysed using Microsoft EXCEL, 2016. Pre and post responses on the Likert scale were analysed using the paired t-test.

After the simulation and debriefing, participants were invited via email to attend focus group interviews to gain better insight into their responses and attitudes towards the simulation sessions. The format and logistics of the interviews were included in a participant information sheet in the email. Participation was voluntary. We aimed for maximal representation from the various groups of healthcare professionals who participated in the simulation. A semi-structured interview was conducted by 2 researchers (NN, JO) in groups of 3 to 5 and interviews were audio-recorded. Two focus group interviews were conducted. Participants were asked questions regarding how they felt, what they learnt and what the benefits of the simulation experience were. Each interview lasted 30 to 40 minutes and were conducted in a quiet room in the PICU. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymised at the point of transcription. Participants were only identified by role in the transcript.

Thematic analysis of the transcripts was performed by the 2 interviewers using an inductive approach. Each interviewer coded the data independently, after which both interviewers discussed the codes and generated common themes together. Data was reviewed for commonality in responses, degree of specificity (detailed explanation), and extensiveness (number of different people who had similar responses). Where there was disagreement, review of the data and existing literature was used for resolution. Descriptive summaries were developed for each theme, and participant quotes provided further evidence for interpretation and recommendations made.

This study was approved by the institutional review board (National Healthcare Group, Domain Specific Review Board, NHG DSRB Ref. 2020/00234) and waiver of consent was obtained.

III. RESULTS

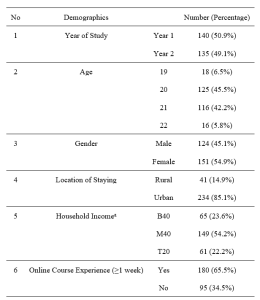

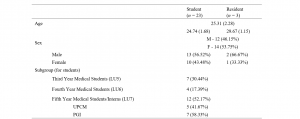

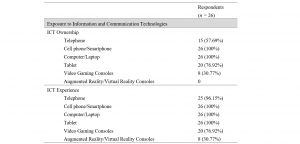

A. Pre- and Post-Simulation Questionnaire Responses

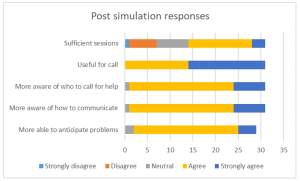

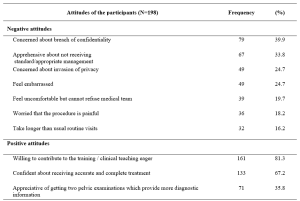

A total of 33 participants took part in the training and completed the pre- and post-simulation questionnaires. There were 19 doctors, 12 nurses and 2 respiratory therapists. Confidence, as assessed by the questionnaire, increased significantly after the simulation in the areas of intubation, use of the PAPR, airway management in a COVID-suspect patient, leading a team and dealing with problems that arise during resuscitation (p < 0.05). Regarding anxiety over intubating a COVID-suspect patient, most participants were less anxious after the simulation (p < 0.05). Interestingly, on looking more closely at the responses, 9% (n=3) of participants were more anxious after the simulation than before they started. 42% (n=14) reported no change in their level of anxiety. Table 1 shows the mean scores of the questions asked in the pre- and post-simulation questionnaire.

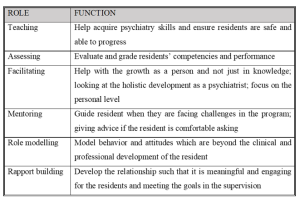

Table 1: Pre- and post-simulation responses

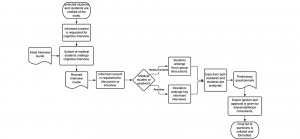

After the simulation training, 96% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that they were more aware of who to call for help and how to communicate effectively when wearing PPE or PAPR while in an isolation room and 93% agreed or strongly agreed that they were more able to anticipate problems. All participants agreed that simulation training was useful in preparing to deal with a similar situation while on call and in fact, 23% disagreed or strongly disagreed that 1 simulation session was sufficient. Figure 1 illustrates the perceived effectiveness of simulation training by participants.

Figure 1: Post-simulation responses on effectiveness of simulation training

B. Focus Group Interviews

Eight participants agreed to focus group interviews, 4 doctors, 3 nurses and 1 respiratory therapist. Comments from the focus group interviews helped to further delineate the benefits and lessons learnt from this simulation exercise. Key benefits were grouped into the following themes:

1) Experiential learning: Participants commented that getting to put theory into practice during the simulation was key to understanding what to expect. Being able to practice before an actual patient encounter helped them to be more prepared. Even simple things like setting an intravenous cannula could not be accomplished with ease. Participants stated that they had to rethink the way that things needed to be done as how they were done previously would not work in this situation. This led to a paradigm shift in the clinical processes and also the application of knowledge. For example, a lesson learnt was that there is a lower threshold for intubation in COVID-19 patients. In the words of a participant about his experience:

“But the fact that you actually go through it, firstly you realize that it takes 3 times the length of the duration of what you would do, and the difficulties in communicating with the people around. So I thought that was the most…an awakening…. the most beneficial part.”

Participants appreciated that this was a complex scenario that was high stakes for the healthcare team as well as for the patient. Getting to practice this, even though it was likely to be an infrequent occurrence, helped with familiarity with protocols and equipment used. Participants also felt that more people should attend this training and that they needed more practice.

2) Increasing confidence: Participants felt that the simulation training was a timely intervention in light of the developing COVID-19 situation. This experience took away the “first-time” feeling and made the participants feel more comfortable with the protective equipment. This took away some of the anxiety and fear about their own safety and the safety of their COVID-19 patients. One participant stated that more practice in simulations may reduce the resistance to wearing the PAPR, which may in itself pose a safety issue if PAPRs are not used when required. They felt that this experience made them a more valuable member to the resuscitation team.

3) Increasing awareness: Participants appreciated the feedback and debriefing that came after the simulation. Experiencing the simulation made taught them to anticipate problems, plan ahead and to prioritize as resources were less accessible than usual. They developed insight into a possible “unconscious incompetence” as they expressed that if they had not gone through the simulation, they would not have known what they did not know and would be inappropriately confident in a real situation. Exploring resource management and considering aspects of waste reduction were thought to be beneficial for future encounters with similar situations. Some of our participants said:

“It really gives you…. the best kind of idea of what to expect in a real life scenario.”

“I would feel quite…. in a sense, bad for the patient that I was doing it for the first time on that patient. So I do feel that it is a responsible thing to do, as healthcare providers that we… that this was actually undertaken.”

“If we had not had this, I probably won’t even have that fear of how terrible it could have been……… But if I had not known, I would still be confident not knowing what I’m expecting.”

Some participants mentioned developing more empathy for colleagues caring for COVID-19 patients through this experience. However, one participant found herself more frustrated after going through the simulation as the experience of managing a resuscitation in this situation was worse than she had thought it would be.

4) Process improvement: In the focus group discussions, participants mentioned the need for process improvement that was discovered while encountering difficulties during the simulation scenario. Communication challenges were brought up multiple times and participants suggested making laminated signs for communication with staff outside the room when assistance was required, having pen, paper and drug labels in the room, as well as using intercoms or walkie-talkies for more efficient communication.

5) Translation: A couple of participants encountered a real subsequent clinical situation which required them to apply skills that they had learnt during the simulation training. The fact that they had gone through the training made them less anxious and more able to take control of the emergency situation. The respiratory therapist in the group expressed more confidence in the nurses that had gone through the simulation training when compared to those who had not when managing a COVID-19 patient. Participants also commented that the skills learnt could be translated to a different institution in the future and perhaps also to a different infective agent. Participants expressed the following:

“And so it would make you, I think… more valuable as a team member in providing care for a COVD patient or any other sort of respiratory pathogen X anywhere.”

“Because I observe that those nurses that attended the simulation, in the actual scenario or in the actual patient handling, they are more confident and competent in doing their PPE and flow of the sequence inside.”

“Because for me, for example, I actually had to initiate and help…coordinate initiation of ECMO for a COVID suspect patient and so I think if not for that…that mock… I would probably have been much more nervous and unsure.”

Key challenges encountered during the simulation were related to the simulation scenario and to the process of simulation itself. The most emphasised challenges encountered during the simulation were cognitive overload and communication barriers. Not only did the team have to deal with a deteriorating patient who was suspected to have COVID-19, they also had to deal with infection control protocols and the inherent challenges that it posed to the resuscitation process. As many tasks needed to be coordinated in a stressful situation, prioritisation was key. Communication barriers came in the form of restricted movement in and out of the isolation room, not being able to use their mobile devices, hearing impairment with the PAPR on and not being able to be heard clearly while wearing the N95 mask. Other challenges raised relating to the scenario were unfamiliarity with the safety equipment as it was not used frequently and having to wait a long time for orders to be carried out. An interesting challenge brought up was a tension between the patient’s safety or well-being and healthcare worker’s own safety. Healthcare professionals frequently put their patients first and in this unique situation, the need for donning personal protective equipment before entering the patient’s environment does not allow for as rapid a response to a deteriorating patient as they are used to:

“I feel like I need to go in as soon as possible but donning the PAPR takes some…. more time than I thought.”

Logistical challenges in planning for this simulation training included the availability and timely attendance of all frontline healthcare workers. With the developing crisis, healthcare professionals were kept busy with their clinical responsibilities, therefore this simulation training was seen as an unwelcome interruption. There was also a perceived resistance to participating by the nurses although the reasons are unclear.

Participants also commented on the design of this simulation training. Prior training in the process of intubation and use of PPE and PAPR were deemed necessary to optimize the benefits of this exercise. Participants appreciated that there were 2 trainers, 1 in the ante-room and 1 in the patient’s room, who were observing different processes and able to give valuable feedback during the debriefing. They also appreciated that the simulation exercise was done in-situ, and therefore was realistic in design.

Suggestions for improvement included providing a variety of clinical scenarios, training junior physicians so that the whole medical team is familiar with the processes, mimicking the typical manpower available on-call in the simulation exercise, and increasing the complexity of the scenarios to address resource allocation issues faced in a pandemic.

IV. DISCUSSION

With the development of the COVID-19 outbreak and patients requiring intensive care, our unit thought it would be imperative to train our frontline staff to be prepared to manage airway emergencies and to be able to resuscitate infected patients. Simulation provides a safe environment for mistakes to be made without compromising patient safety (Ziv et al., 2000). It also provides a platform for deliberate practice (Ericsson, 2004) and not allow for a chance clinical encounter to develop expertise in an area. Simulation has also been utilised in high consequence infectious outbreak training, resulting in improved self-efficacy, reduced anxiety and improved inter-professional teamwork (Marrs et al., 2019; O’Keeffe et al., 2016). As the consequences for patient and individual safety were high in the COVID-19 outbreak, we felt it was prudent to use simulation-based education as a platform for upskilling our staff.

Despite training in the use of personal protection equipment (PPE), including the powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR), Watson et al found that there was an inadequate adherence to the use of PPE and resuscitation guidelines in simulated cardiac arrest in paediatric influenza (H1N1) patients (Watson et al., 2011). Intensive care procedures have been found to be more difficult, stressful and uncomfortable when performed in PPE (Grillet et al., 2015). Simulation training has also been able to detect breaches in infection control procedures (Seet et al., 2009) and potentially improve compliance with infection prevention measures (Tan et al., 2021).

For the above reasons, healthcare professionals who worked in the paediatric intensive care unit were put through a mandatory simulation-based training session on airway management of a deteriorating patient who was suspected to have COVID-19 infection. An in-situ model was chosen as it could be used to evaluate system competence and identify latent conditions that predispose to medical error (Patterson et al., 2013). In this study, in situ simulation provided a means to identify areas for process improvement and knowledge gaps. It provided the ability to test the actual clinical care system, including equipment, processes, and staff response. This form of “just-in-time” training takes place in close proximity to the clinical encounter in a focused concise manner (Itoh et al., 2019). This provides the participants with contextually relevant hands-on experience in dealing with an impending low-frequency event before it actually happens. This has shown to improve confidence levels and clinical skills (Sam et al., 2012).

As expected, there was improvement in self-efficacy as shown in the improvement in pre- and post-simulation responses for all questions relating to management of the patient and clinical team. This has been shown in many previous studies using simulation as a methodology (McLaughlin et al., 2019; Secheresse et al., 2020). Evidence does suggest that clinicians have a limited ability for self-assessment of competence (Davis et al., 2006) and self-assessment. From the Kirkpatrick levels of evaluation, this would be a level 2 evaluation of knowledge, skills and attitudes (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006). From the qualitative data, the benefits that were emphasised where related to experiential learning and increasing confidence as well as awareness. Kolb’s framework of experiential learning includes the phases of concrete experience and reflective observation (Kolb, 1984). These phases were evident in the simulation experience. Participants reflected that theoretical knowledge does not guarantee perfect execution in real life. The cognitive load of managing a high consequence, low incidence event along with the concomitant risk of exposure to a highly infectious agent makes clinical decision making harder. Although the participants underwent prior PPE training, they appreciated the opportunity to put it all into practice.

There was a definite signal for increased self-efficacy and confidence. This is seen in the literature on simulation-based healthcare education across disciplines (Bragard et al., 2018; Cohen et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2011; Fouilloux et al., 2019). A study on influenza pandemic preparedness showed that simulation improved staff confidence and also demonstrated that many tasks and procedures took longer to complete with the implementation of guidelines (Phin et al., 2009). This was similarly evident in our participants as they became more aware of the challenges and the additional time needed for most resuscitative actions due to infection control requirements. Going through the simulated scenario and debriefing made them feel more prepared for an actual emergency. In addition, participants highlighted that the simulation experience alleviated anxiety as it successfully removed the “first-time” feeling for them, and felt that it was the responsible thing to do for healthcare workers in the midst a public health crisis. Lessons learnt by the participants included anticipatory planning, prioritisation and resource management. We had a small signal that the skills learnt translated to real life as one participant had a clinical encounter that required initiating extracorporeal life support in a patient with suspected COVID-19. She reported feeling relieved that she had the simulation experience before the real-life clinical encounter, and felt she was less nervous because of her prior stimulated experience. A respiratory therapist also observed that the nurses who he worked with in the PICU who had gone through the simulation seemed more confident and more aware of the necessary processes when intubating suspected COVID-19 patients.

An interesting phenomenon was the signal that there was an increase in anxiety levels after participants went through the simulation as seen in the pre- and post-simulation response. A possible explanation could be what participants brought up in the interviews about the simulation and debriefing revealing their “unconscious incompetence”. This made them more aware of the complexity and so increased their anxiety with dealing with intubation in a COVID-19 patient. Other studies in the literature generally report a reduction in anxiety after simulation (Bragard et al., 2019; Shrestha et al., 2019, 2020). This may not be a negative impact arising from the simulation experience itself as it may reflect increased awareness in an uncommon, yet stressful and complex clinical situation for our healthcare workers. Anxiety levels in frontline healthcare workers in a pandemic may also be due to other factors such as being at higher risk of exposure to COVID-19 at work and the possibility of bringing the infection home to their family (Holmes et al., 2020; Shanafelt et al., 2020).

Another benefit derived from running this simulation-based training is the process improvement suggestions made by the participants. This is a known benefit of simulation (Paige et al., 2018) and was utilised during the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak (Abrahamson et al., 2005). The main challenge faced by participants during this scenario was the communication barrier which arose from not being able to communicate with personnel outside the room and the presence of the PPE and PAPR physically obstructing hearing and clarity of speech. Also, restriction of movement in and out of the patient’s room experienced during simulation highlighted the need to rethink resuscitation practices when dealing with COIVD patients. These systemic issues surfaced allowed us to brainstorm for practical solutions as a unit, and some have been implemented in our PICU. We have trialled the use of infant monitors as a 2-way communication device. Pre-packed resuscitation drug kits containing intravenous adrenaline and intravenous atropine as well as pre-packed intravenous cannulation disposables have been put in every isolation room so that these would be easily accessible in an emergency. As suggested by the participants, we have also extended the simulation training to include all junior doctors in the department, more nurses and all respiratory therapists in the PICU to facilitate better teamwork. We are also exploring the provision of a dedicated COVID-19 crash cart to minimise waste and prevent cross-contamination.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, the sample size is small and selection bias is possible due to the study design. Next, focus group interviews were conducted with a small subset of the participants who agreed to participate, and therefore our findings may not have been representative of the entire cohort. However, we are reassured by the fact that each healthcare professional group that took part in the simulation training was represented in the focus groups. As this simulation exercise was designed to be “just in time” training and we were limited by the urgency of the situation as well as the need to train as many staff in the shortest amount of time, we could only conduct a one-time simulation scenario specific to the highest risk procedure in resuscitating a suspected COVID-19 patient. We were therefore not able to assess the impact of this training on the subsequent performance of the participants either in another simulated scenario or a real life one.

V. CONCLUSION

Simulation-based training is a useful tool for infectious disease outbreak preparedness for the healthcare team. It improves confidence and awareness around managing emergencies while maintaining personal protection through deliberate practice in a safe environment. It also provides an opportunity for process improvement in a new and evolving pandemic situation. It was well-received by the participants and perhaps more sessions are needed for adequate practice. This is limited by the resource-intensive nature of in-situ simulation and the heavy clinical workload at this time of crisis. Further research will need to be done to determine if simulation-based training has a significant impact on actual clinical practice

Notes on Contributors

Nicola Ngiam conceptualised and designed the study, collected data, analysed and interpreted it, drafted the manuscript and approved the final version submitted.

Kristy X Fu did the background work and literature review, assisted in drafting the manuscript and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted.

Jacqueline SM Ong designed the study, collected data, interpreted it, critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval has been granted by National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (Ref: NHG DSRB Ref. 2020/00234)

Data Availability

Transcripts from the interviews are confidential and the authors do not have consent to upload onto a repository. Data from questionnaires can be made available on request.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Dimple Rajgor for helping with formatting, and submission of the manuscript for publication.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Interest

The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

Abrahamson, S. D., Canzian, S., & Brunet, F. (2005). Using simulation for training and to change protocol during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Critical Care, 10(1), R3. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc3916

Booth, C. M., Matukas, L. M., Tomlinson, G. A., Rachlis, A. R., Rose, D. B., Dwosh, H. A., Walmsley, S. L., Mazzulli, T., Avendano, M., Derkach, P., Ephtimios, I. E., Kitai, I., Mederski, B. D., Shadowitz, S. B., Gold, W. L., Hawryluck, L. A., Rea, E., Chenkin, J. S., Cescon, D. W., Poutenan, S.M. & Detsky, A. S. (2003). Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA, 289(21), 2801-2809. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885

Bragard, I., Farhat, N., Seghaye, M.-C., Karam, O., Neuschwander, A., Shayan, Y., & Schumacher, K. (2019). Effectiveness of a high-fidelity simulation-based training program in managing cardiac arrhythmias in children: A randomized pilot study. Pediatric Emergency Care, 35(6), 412-418. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000931

Bragard, I., Seghaye, M.-C., Farhat, N., Solowianiuk, M., Saliba, M., Etienne, A.-M., & Schumacher, K. (2018). Implementation of a 2-day simulation-based course to prepare medical graduates on their first year of residency. Pediatric Emergency Care, 34(12), 857-861. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000930

Caputo, K., Byrick, R., Chapman, M., Orser, B., & Orser, B. (2006). Intubation of SARS patients: Infection and perspectives of healthcare workers. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia, 53(2), 122-129. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03021815

Cohen, E. R., Barsuk, J. H., Moazed, F., Caprio, T., Didwania, A., McGaghie, W. C., & Wayne, D. B. (2013). Making July safer: Simulation-based mastery learning during intern boot camp. Academic Medicine, 88(2), 233-239. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31827bfc0a

Davis, D. A., Mazmanian, P. E., Fordis, M., Van Harrison, R., Thorpe, K. E., & Perrier, L. (2006). Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. JAMA, 296(9), 1094-1102. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1094

Ericsson, K. A. (2004). Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Academic Medicine, 79(10), S70-S81. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022

Fisher, N., Eisen, L. A., Bayya, J. V., Dulu, A., Bernstein, P. S., Merkatz, I. R., & Goffman, D. (2011). Improved performance of maternal-fetal medicine staff after maternal cardiac arrest simulation-based training. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 205(3), e1-e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.012

Fouilloux, V., Gran, C., Guervilly, C., Breaud, J., El Louali, F., & Rostini, P. (2019). Impact of education and training course for ECMO patients based on high-fidelity simulation: A pilot study dedicated to ICU nurses. Perfusion, 34(1), 29-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267659118789824

Grillet, G., Marjanovic, N., Diverrez, J., Tattevin, P., Tadié, J., & L’Her, E. (2015). Intensive care medical procedures are more complicated, more stressful, and less comfortable with Ebola personal protective equipment: A simulation study. The Journal of Infection, 71(6), 703-706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2015.09.003

Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Silver, R. C., & Everall, I. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547-560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Itoh, T., Lee-Jayaram, J., Fang, R., Hong, T., & Berg, B. (2019). Just-in-Time Training for Intraosseous Needle Placement and Defibrillator Use in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatric Emergency Care, 35(10), 712-715. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001516

Kirkpatrick, D., & Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kolb, D. (1984). The experiential learning theory of development. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (pp. 132-160). Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 132-160.

Lau, J., Fung, K., Wong, T., Kim, J., Wong, E., Chung, S., Ho, D., Chan, L., Lui, S., & Cheng, A. (2004). SARS transmission among hospital workers in Hong Kong. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(2), 280-286. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1002.030534

Marrs, R., Horsley, T. L., Hackbarth, D., & Landon, E. (2019). High consequence infectious diseases training using interprofessional simulation and TeamSTEPPS. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 615-620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2019.10.007

McLaughlin, C., Barry, W., Barin, E., Kysh, L., Auerbach, M. A., Upperman, J. S., Burd, R. S., & Jensen, A. R. (2019). Multidisciplinary simulation-based team training for trauma resuscitation: A scoping review. Journal of Surgical Education, 76(6), 1669-1680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.05.002

O’Keeffe, D., Bradley, D., Evans, L., Bustamante, N., Timmel, M., Akkineni, R., Mulloy, D., Goralnick, E., & Pozner, C. (2016). Ebola Emergency Preparedness: Simulation Training for Frontline Health Care Professionals. MedEdPORTAL, 12, 10433-10433. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10433

Paige, J. T., Fairbanks, R. J. T., & Gaba, D. M. (2018). Priorities related to improving healthcare safety through simulation. Simulation in Healthcare, 13(3S), S41-S50. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000295

Patterson, M., Geis, G., Falcone, R., LeMaster, T., & Wears, R. (2013). In situ simulation: detection of safety threats and teamwork training in a high risk emergency department. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(6), 468-477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000942

Phin, N., Rylands, A., Allan, J., Edwards, C., Enstone, J., & Nguyen-Van-Tam, J. (2009). Personal protective equipment in an influenza pandemic: a UK simulation exercise. Journal of Hospital Infection, 71(1), 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2008.09.005

Sam, J., Pierse, M., Al-Qahtani, A., & Cheng, A. (2012). Implementation and evaluation of a simulation curriculum for paediatric residency programs including just-in-time in situ mock codes. Paediatrics & Child Health, 17(2), e16-20. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/17.2.e16

Secheresse, T., Pansu, P., & Lima, L. (2020). The impact of full-scale simulation training based on Kolb’s learning cycle on medical prehospital emergency teams: A multilevel assessment study. Simulation in Healthcare, 15(5), 335-340. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000461

Seet, R., Lim, E., Oh, V., Ong, B., Goh, K., Fisher, D., Ho, K., & Yeoh, K. (2009). Readiness exercise to combat avian influenza. QJM : Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 102(2), 133-137. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcn159

Shanafelt, T., Ripp, J., & Trockel, M. (2020). Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA, 323(21), 2133-2134. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5893

Shrestha, R., Badyal, D., Shrestha, A., & Shrestha, A. (2020). In-situ simulation-based module to train interns in resuscitation skills during cardiac arrest. Advances in Medical education and Practice, 11, 271-285. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S246920

Shrestha, R., Shrestha, A. P., Shrestha, S. K., Basnet, S., & Pradhan, A. (2019). Interdisciplinary in situ simulation-based medical education in the emergency department of a teaching hospital in Nepal. International Journal of Emergency Medicine, 12(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-019-0235-x

Tan, K. W., Ong, H. K., & Mok, U. S. (2021). Using simulation and inter-professional education to teach infection prevention during resuscitation. The Asia Pacific Scholar, 6(1), 93-108. https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-1/OA2229

The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences University of Oxford. (2020). Global Covid-19 case fatality rates. https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/global-covid-19-case-fatality-rates/. Accessed April 26, 2020.

The Novel Coronavirus Pnuemonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team. (2020). The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Weekly, 2(8), 113-122. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2020.032

Watson, C., Duval-Arnould, J., McCrory, M., Froz, S., Connors, C., Perl, T., & Hunt, E. (2011). Simulated pediatric resuscitation use for personal protective equipment adherence measurement and training during the 2009 influenza (H1N1) pandemic. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 37(11), 515-523. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37066-3

Wax, R. S., & Christian, M. D. (2020). Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie, 67(5), 568–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x

World Health Organization. (2020). Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019- nCoV). Retrieved 6 April, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)

Wu, Z., & McGoogan, J. (2020). Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA, 323(13), 1239-1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

Ziv, A., Small, S. D., & Wolpe, P. R. (2000). Patient safety and simulation-based medical education. Medical Teacher, 22(5), 489-495. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590050110777

Zuo, M., Huang, Y., Ma, W., Xue, Z., Zhang, J., Gong, Y., & Che, L. (2020). Expert recommendations for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with Noval Coronavirus Disease 2019. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal, 35(2), 105–109. https://doi.org/10.24920/003724

*Nicola Ngiam

Centre for Healthcare Simulation,

National University of Singapore,

14 Medical Dr,

Singapore 117599

Email: nicola_ngiam@nuhs.edu.sg

Submitted: 5 July 2021

Accepted: 13 September 2021

Published online: 5 April, TAPS 2022, 7(2), 6-16

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2022-7-2/OA2654

Ming-Jung Ho1,2, Yu-Che Chang3,4,5 & Steven L. Kanter6

1Center for Innovations and Leadership in Education, Georgetown University Medical Center (CENTILE), Washington, D.C., United States; 2Department of Family Medicine, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington D.C., United States; 3Chang Gung Medical Education Research Centre (CG-MERC), Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Taoyuan, Taiwan; 4Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taoyuan, Taiwan; 5Department of Emergency Medicine, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taoyuan, Taiwan; 6Association of Academic Health Centers, Washington, D.C., United States.

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic forced medical schools worldwide to transition online. While there are ample reports about medical education adaptations to this crisis, there are limited studies evaluating the impact.

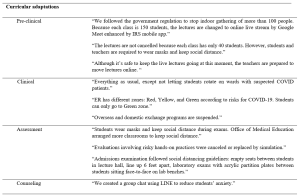

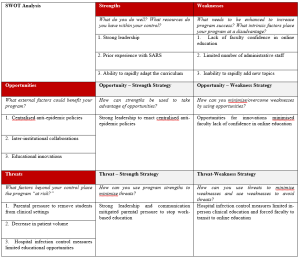

Methods: This study includes a case study of how Taiwanese medical school deans maintained in-person education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, it demonstrates how SWOT analyses can help medical educators reflect on adaptations during the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises. This study employed two online surveys and a semi-structured interview regarding curricular adaptations. Eligible participants were deans or associate deans of all medical schools in Taiwan.