Examiner training for the Malaysian anaesthesiology exit level assessment: Factors affecting the effectiveness of a faculty development intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic

Submitted: 30 June 2022

Accepted: 31 October 2022

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 26-34

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/OA2834

Noorjahan Haneem Md Hashim1, Shairil Rahayu Ruslan1, Ina Ismiarti Shariffuddin1, Woon Lai Lim1, Christina Phoay Lay Tan2 & Vinod Pallath3

1Department of Anaesthesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 2Department of Primary Care Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia; 3Medical Education Research & Development Unit, Dean’s Office, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya, Malaysia

Abstract

Introduction: Examiner training is essential to ensure the trustworthiness of the examination process and results. The Anaesthesiology examiners’ training programme to standardise examination techniques and standards across seniority, subspecialty, and institutions was developed using McLean’s adaptation of Kern’s framework.

Methods: The programme was delivered through an online platform due to pandemic constraints. Key focus areas were Performance Dimension Training (PDT), Form-of-Reference Training (FORT) and factors affecting validity. Training methods included interactive lectures, facilitated discussions and experiential learning sessions using the rubrics created for the viva examination. The programme effectiveness was measured using the Kirkpatrick model for programme evaluation.

Results: Seven out of eleven participants rated the programme content as useful and relevant. Four participants showed improvement in the post-test, when compared to the pre-test. Five participants reported behavioural changes during the examination, either during the preparation or conduct of the examination. Factors that contributed to this intervention’s effectiveness were identified through the MOAC (motivation, opportunities, abilities, and communality) model.

Conclusion: Though not all examiners attended the training session, all were committed to a fairer and transparent examination and motivated to ensure ease of the process. The success of any faculty development programme must be defined and the factors affecting it must be identified to ensure engagement and sustainability of the programme.

Keywords: Medical Education, Health Profession Education, Examiner Training, Faculty Development, Assessment, MOAC Model, Programme Evaluation

Practice Highlights

- A faculty development initiative must be tailored to faculty’s learning needs and context.

- A simple framework of planning, implementing, and evaluating can be used to design a programme.

- Target outcome measures and evaluation plans must be included in the planning process.

- The Kirkpatrick model is a useful tool to use in programme evaluation: to answer if the programme has met its objectives.

- The MOAC model is a useful tool to explain why a programme has met its objective.

I. INTRODUCTION

Anaesthesiology specialist training in Malaysia comprises a 4-year clinical master’s programme. At the time of our workshop, five local public universities offer the programme. The course content is similar in all universities, but the course delivery may differ to align with each university’s rules and regulations. The summative examinations are held as a Conjoint Examination. Examiners include lecturers from all five universities, specialists from the Ministry of Health and external examiners from international Anaesthesiology training programmes. The examination consists of a written and a viva voce examination. The areas examined are the knowledge and cognitive skills in patient management.

A speciality training programme’s exit level assessment is an essential milestone for licensing. In our programme, the exit examination occurs at the end of the training before trainees practise independently in the healthcare system and are eligible for national specialist registration. Therefore, aligning the curriculum and assessment to licensing requirements is necessary.

Examiners play an important role during this high-stakes summative examination, making decisions regarding allowing graduating trainees to work as specialists in the community. Therefore, examiners must understand their role. In recent years, the anaesthesiology training programme providers in Malaysia have been taking measures to improve the validity of the examination. These include a stringent vetting process to ensure examination content reflects the syllabus, questions are unambiguous, and the examiners agree on the criteria for passing. However, previous examinations revealed that although examiners were clear on the aim of the examination, some utilised different assessment approaches, which were possibly coloured by personal and professional experiences, and thus needed constant calibration on the passing criteria. In addition, during examiner discussions, different examiners were found to have different skill levels in constructing focused higher-order questions and were not fully aware of potential cognitive biases that may affect the examination results.

These insights from previous examinations warranted a specific skill training session to ensure the trustworthiness of the examination process and results (Blew et al., 2010; Iqbal et al., 2010; Juul et al., 2019, Chapter 8, pp. 127-140; McLean et al., 2008). The examiners and the Specialty committee were keen to ensure that these issues were addressed with a training programme that complements the current on-the-job examiner training.

II. METHODS

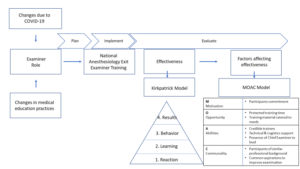

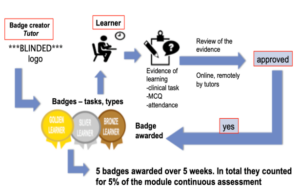

An examiner training module was developed using McLean’s adaptation of Kern’s framework for curriculum development: Planning, Implementation and Evaluation (McLean et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2015). A conceptual framework for the examiner training programme was drawn up from the programme’s conception stage to the evaluation of its outcome, as illustrated in Figure 1 (Steinert et al., 2016).

Figure 1: The conceptual framework for the examiner training programme and evaluation of its effectiveness

A. Planning

Three key focus areas were identified for the training programme: (1) Performance Dimension Training (PDT); (2) examiner calibration with Frame-Of-Reference Training (FORT); as well as (3) identifying factors affecting the validity of results and measures that can be taken to prevent them.

1) Performance dimension training (Feldman et al., 2012): The aim was to improve examination validity by reducing examiner errors or biases unrelated to the examinees’ targeted performance behaviours. Finalised marking schemes outlining competencies to be assessed required agreement by all the examiners ahead of time. These needed to be clearly defined and easily understood by all the examiners, and consistency was key to reducing examiner bias.

2) Examiner calibration with Frame-of-Reference Training (FORT) (Newman et al., 2016): Differing levels of experience among all the participants meant that there were differing expectations and performances among them. The examiner training programme needed to assist examiners in resetting expectations and criteria for assessing the candidates’ competencies. This examiner calibration was achieved using pre-recorded simulated viva sessions in which the participants rated candidates’ performances in each simulated viva session and received immediate feedback on their ability and criteria for scoring the candidates.

3) Identifying factors affecting the validity of results (Lineberry, 2019): Factors that may affect the validity of examination results may be related to construct underrepresentation (CU), where the results only reflect one part of an attribute being examined; or construct-irrelevant variance (CIV), where the results are being affected by areas or issues other than the attribute being examined.

An example of CU is sampling issues where only a limited area of the syllabus is examined, or an answer key is limited by the availability of evidence or content expertise.

Examples of CIV include the different ways a concept can be interpreted in different cultures or training centres, ambiguous questions, examiner cognitive biases, examiner fatigue, examinee language abilities, and examinees guessing or cheating. The examiner training programme was designed with the objectives listed in Table 1.

|

Malaysian Anaesthesiology Exit Level Examiner Training Programme |

|

1. Participants should be able to define the purpose and competencies to be assessed in the viva examination. |

|

2. Participants should be able to construct high-order questions (elaborating, probing, and justifying). |

|

3. Participants should be able to agree on anchors on rating scales of examination and narrow the range of ratings for the same encounter everyone observes. |

|

4. Participants should be able to calibrate the scoring of different levels of responses. |

Table 1: Objectives of the Faculty Development Intervention

B. Implementation

The faculty intervention programme was designed as a one-day online programme to be attended by potential examiners for the Anaesthesiology Exit Examination. The programme objectives were prioritised from the needs assessment and designed based on Tekian & Norcini’s recommendations (Tekian & Norcini, 2016). Due to time constraints, training was performed using an online platform closer to the examination dates after obtaining university clearance on confidentiality regarding assessment issues.

The structure and contents of the examiner training programme are outlined in Table 2 and is further elaborated in Appendix A.

|

General content |

Specific content |

|

Lectures |

1. Orientation to the examination regulations, objectives, structure and format of the final examination. |

|

|

2. Ensuring validity of the viva examination: elaborating on the threats present to the process and how to mitigate these concerns. |

|

|

3. Creating high-order questions based on competencies to be assessed and promoting appropriate examiner behaviours through consistency and increasing reliability. |

|

|

4. Utilising marking schemes, anchors and making inferences with:

|

|

Experiential learning sessions |

1. Participants discuss and agree on the competencies to be assessed. 2. Participants work in groups to construct questions based on a given scenario and competencies to be assessed. 3. Participants finalise a rating scale to be used in the examination. 4. Participants observe videos of simulated examination candidates performing at various levels of competencies and rate their performance. The discussion here focused on the similarities and differences between examiners. |

|

Participant feedback and evaluation |

A question-and-answer session is held to iron out any doubts and queries from the participants. |

Table 2: Contents and structure of the examiner training programme

Based on the objectives, the organisers invited a multidisciplinary group of facilitators. The group consisted of anaesthesiologists, medical education experts in assessment and faculty development, and a technical and logistics support team to ensure efficient delivery of the online programme.

A multimodal approach to delivery was adopted to accommodate the diversity of the examiner group (gender, seniority, subspeciality, and examination experience). Explicit ground rules were agreed upon to underpin the safe and respectful learning environment. The educational strategy included interactive lectures, hands-on practice using rubrics created and calibration using video-assisted scenarios. The programme objectives were embedded and reinforced with each strategy. Pre- and post-tests were performed to help participants gauge their learning and assist the programme organisers in evaluating the participants’ learning.

This would be the first time such a programme was held within the local setting. Participants were all anaesthesiologists by profession, were actively involved in clinical duties within a tertiary hospital setting and consented to participate in this programme. As potential examiners, they all had prior experience as observers of the examination process, with the majority having previous experience as examiners as well.

The programme was organised during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and was managed on a fully online platform to ensure safety and minimise the time taken away from clinical duties. In addition, participants received protected time for this programme, a necessary luxury as anaesthesiologists were at the forefront of managing the pandemic.

C. Evaluation

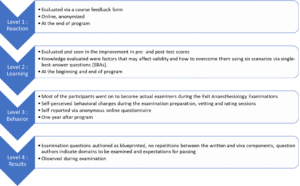

The Kirkpatrick model (McLean et al., 2008; Newstrom, 1995;) was used to evaluate the programme’s effectiveness described and elaborated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Kirkpatrick model, elaborated for this programme

The MOAC model (Vollenbroek, 2019), expanded from the MOA (Marin-Garcia & Martinez Tomas, 2016) model by Blumberg & Pringle (Blumberg & Pringle, 1982) was used to examine factors that contributed to the effectiveness of the programme. Motivation, opportunity, ability, and communality are factors that drives action and performance.

III. RESULTS

Eleven participants attended the programme. These participants were examiners for the 2021 examinations from the university training centres and the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Only one of the participants would be a first-time examiner in the Exit Examination. Four of the would-be examiners could not attend due to service priorities.

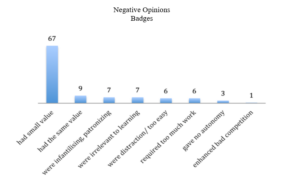

A. Level 1: Reaction

Seven of the eleven participants completed the programme evaluation form, which is openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20189309.v1 (Tan & Pallath, 2022). All of them rated the programme content as useful and relevant to their examination duties and stated that the content and presentations were pitched at the correct level, with appropriate visual aids and reference materials. The online learning opportunity was also rated as good.

All seven also aimed to make behavioural changes after attending the programme, as indicated below. Some of the excerpts include:

“I am more cognizant of the candidates’ understanding to questions and marking schemes”

“Yes. We definitely need the rubric/marking scheme for standardisation. Will also try to reduce all the possible biases as mentioned in the programme.”

“Yes, as I will be more agreeable to question standardisation in viva examination because it makes it fairer for the candidates.”

The participants also shared their understanding of the importance of standardisation and examiner training and would recommend this programme to be conducted annually. They agreed that the examiner training programme should be made mandatory for all new examiners, with the option of refresher courses for veteran examiners if appropriate.

B. Level 2: Learning

All 11 participants completed the pre-and post-tests. The data supporting these findings of this is openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20186582.v1 (Md Hashim, 2021). The participants’ marks in both tests are shown in Appendix B. The areas that showed improvement in scores were identifying why under-sampling is a problem and methods to prevent validity threats. Understanding the source of validity threat from cognitive biases showed a decline in scores (question 2 with scores of 11 to 8 and question 3 with scores of 10 to 8), respectively.

Comparing the post-test scores to pre-test scores, four participants showed improvement, four showed no change (one of the participants answered all questions correctly in both tests) and three participants showed a decline in test scores.

C. Level 3: Behavioural Change

Six participants responded to the follow-up questionnaire, which is openly available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20186591.v2 (Md Hashim, 2022). This questionnaire was administered about a year after the examiner training programme and after the completion of two examinations. Only one respondent did not make any self-perceived behavioural change while preparing the examination questions and conducting the viva examinations. Two respondents did not make any changes while marking or rating candidates.

The specific changes in the three areas of behavioural change that were consciously noted by the respondents were explored. Respondents reported increased awareness and being more systematic in question preparation, making questions more aligned to the curriculum, preparing better quality questions, and being more cognizant of candidates’ understanding of the questions.

They also reported being more objective and guided during marking and rating as the passing criteria were better defined and structured.

Regarding the conduct of the viva examination, respondents shared that they were better prepared during vetting and felt it was easier to rate candidates as the marking schemes and questions were standardised and could ensure candidates could answer all the required questions to pass.

D. Level 4: Results

The examiners who attended the training programme were able to prepare questions as blueprinted and were able to identify areas to be examined and provided recommended criteria for passing each question. This has led to a smooth vetting process and examination.

E. Factors Affecting Effectiveness

Even though the programme was not attended by all the potential examiners, those who did were committed to the idea of a fairer and more transparent examination process. This formed the motivation aspect of the model.

In terms of opportunity, protected training time is important, followed by prioritising the content of the training material according to the most pressing needs.

The ability aspect encompassed the abilities of the facilitators and participants. To emphasise the learning process, credible trainers were invited to this programme to facilitate the lectures and experiential learning sessions. In this aspect, the Faculty Development team comprised an experienced clinician, a basic medical scientist, and an anaesthesiologist, all with medical education qualifications and were vital in ensuring the success of this programme. The whole team was led by the Chief Examiner who focused on the dimensions to be tested and calibrated, while simultaneously managing the expectations of the examiners and their abilities to give and accept feedback. Communication and the skill to be receptive to the proposed changes were also crucial to make the intervention work.

In terms of communality, all the participants were of similar professional backgrounds and shared the common realisation that this training programme was essential and would only yield positive results. Hence this ensured the programme’s overall success.

IV. DISCUSSION

The progressive change seen in this attempt to improve the examination system is aligned with the general progress in medical education. Training of examiners is important (Holmboe et al., 2011), as it is not the tool used for assessment, but rather the person using the tool, that makes the difference. As it is difficult to design the ‘perfect tool’ for performance tests and redesigning a tool only changes 10% of the variance in rating (Holmboe et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2003), educators must now train the faculty in observation and assessment. It is not irrational to extrapolate this effect on written and oral examinations. Holmboe et al. (2011) also share the reasons for a training programme for assessors, which are changing curriculum structure, content and delivery and emerging evidence regarding assessment, building a system reserve, utilising training programmes as opportunities to identify and engage change agents and allow the faculty to form a mental picture of how changes will affect them and improve practice. Enlisting the help and support of a respected faculty member during training will promote the depth and breadth of change.

Khera et al. (2005) described their paediatric examination experiences, in which the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health defined examiners’ competencies, selection process and training programme components. The training programme included principles of assessment, examination design, writing questions, interpersonal skills, professional attributes, managing diversity, and assessing the examiners’ skills. They believe these contents will ensure the assessment is valid, reliable, and fair. As Anaesthesiology examiners have different knowledge levels and experiences, it had been crucial to assess their learning needs and provide them with appropriate learning opportunities.

In the emergency brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, online training was the safest and most feasible platform for conducting this programme. Online faculty development activities have the perceived advantages of being convenient, flexible, and allowing interdisciplinary interaction and providing an experience of being an online student(Cook & Steinert, 2013). Forming the facilitation team together with the dedicated technical and logistics team and creating a chat group prior to conducting the programme were key in anticipating and handling communication and technical issues (Cook & Steinert, 2013).

Though participants were engaged and the results of the workshop were encouraging, the programme delivery and the content will be reviewed based on the feedback received. The convenience of an online activity must be balanced with the participant engagement and facilitator presence of a face-to-face-activity. Since the results of both methods of delivery differs (Arias et al., 2018; Daniel, 2014; Kemp & Grieve, 2014), the best solution may to ask the participants what would best work for them, as they are adult learners and experienced examiners. The programme must be designed with participants involvement, with opportunities to participate and engaging facilitators and support teams that would be able to support the participants’ learning need (Singh et al., 2022).

At the end of the programme, the effectiveness of the programme was measured by referencing the Kirkpatrick model. The Kirkpatrick model (Newstrom, 1995; Steinert et al., 2006) was the most helpful in helping us identify the success of the intervention, which included behavioural change. Measuring behavioural change and impact on the examination results, organisational changes and changes in student learning may be difficult and may not be directly caused by a single intervention (McLean et al., 2008). The key, is perhaps to involve examiners, students and other stakeholders in the evaluation process, using various validated tools, and to ensure that the effort is ongoing, with sustained support, guidance and feedback (McLean et al., 2008).

To explain the overall effectiveness of the programme (with regards to reaction, learning and behavioural change), the MOAC model (Vollenbroek, 2019) expanded from the original MOA model was used. The MOAC model not only describes factors that affect an individual’s performance in a group, but also the group behaviour.

Motivation is an important driving force of action, and members are more motivated when a subject becomes relevant on a personal level, leading to action. The motivation to be informed and to improve has led to active participation in the knowledge sharing session, processing new information presented in the programme and adopting changes learnt during the programme. Presence of a group of motivated individuals with the same goals supported each other’s learning.

Opportunity, especially time, space and resources, must be allocated to reflect the value and relevance of any activity. Work autonomy, allows professionals to engage in what they consider relevant or important, and be accountable for their work outcomes. Facilitating conditions, for example, technology, facilitators, and a platform to practise what is being learnt are also important aspects of opportunity. Allowing protected time with the appropriate facilitating conditions, indicates institutional support and has enabled participants to fully optimise the learning experience.

Ability positively affects knowledge exchange and willingness to participate. Having prior knowledge improves a participant’s ability to absorb and utilise new knowledge. The programme participants, being experienced clinical teachers and examiners are fully aware of their capabilities and are able to process and share important information. Experienced faculty development facilitators who are also clinical teachers and examiners were able to identify areas to focus and provide relevant examples for application.

Communality is the added dimension to the original MOA model. Participants of this programme are members in a complex system, who already know each other. Having shared identity, language and challenges have allowed them to develop trust while pursuing the common goal of improving the system they were working in. This facilitated knowledge sharing and behavioural change.

The limitation in our programme is the small sample size. However, we believe that is important to review the effectiveness of a programme, especially with regards to behavioural change, and to share how other programmes can benefit from using the frameworks we shared. The findings from this programme will also inform how we conduct future faculty development programmes. With pandemic restrictions lifted, we hope to conduct this programme face-to-face, to facilitate engagement and communication.

V. CONCLUSION

For this faculty development programme to succeed, targets for success must first be defined and factors that contribute to its success need to be identified. This will ensure active engagement from the participants and promote the sustainability of the programme.

Notes on Contributors

Noorjahan Haneem Md Hashim designed the programme, assisted in content creation, curation and matching learning activities, moderated the programme, and conceptualised and wrote this manuscript.

Shairil Rahayu Ruslan participated as a committee of the programme, assisted as a simulated candidate during the training sessions, as well as contributed to the conceptualisation, writing, and formatting of this manuscript. She also compiled the bibliography and cross-checked the references for this manuscript.

Ina Ismiarti Shariffuddin created the opportunity for the programme (Specialty board and interdisciplinary buy-in, department funding), prioritised the programme learning outcomes, chaired the programme, and contributed to the writing and review of this manuscript.

Woon Lai Lim participated as a committee member of the programme and contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Christina Phoay Lay Tan designed and conducted the faculty development training programme, and reviewed and contributed to the writing of this manuscript. She also cross-checked the references for this manuscript.

Vinod Pallath designed and conducted the faculty development training programme, and reviewed and contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

All authors verified and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was applied for the follow-up questionnaire that was distributed to the participants, which was approved on the 6th of May 2022 (Reference number: UM.TNC2/UMREC_1879). The programme evaluation and pre- and post-tests are accepted as part of the programme evaluation procedures.

Data Availability

De-identified individual participant data collected are available in the Figshare repository immediately after publication without an end date, as below :

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20189309.v1

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20186582.v1

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20186591.v2

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are freely available for view from the Figshare data repository. However, the reuse and resharing of the programme evaluation form, pre- and posttest questions, as well as followup questionnaire, despite being easily accessible from the data repository, should warrant a reasonable request from the corresponding author out of courtesy.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Selvan Segaran and Dr Siti Nur Jawahir Rosli from the Medical Education, Research and Development Unit (MERDU) for their logistics and technical support in all stages of this programme; Professor Dr Jamuna Vadivelu, Head, MERDU for her insight and support; Dr Nur Azreen Hussain and Dr Wan Aizat Wan Zakaria from the Department of Anaesthesiology, UMMC and UM, for their acting skills in the training videos; and the Visibility and Communication Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaya for their video editing services.

Funding

There is no funding source for this manuscript.

Declaration of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest among the authors of this manuscript.

References

Arias, J. J., Swinton, J., & Anderson, K. (2018). Online vs. face-to-face: A comparison of student outcomes with random assignment. E-Journal of Business Education & Scholarship of Teaching, 12(2), 1–23. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1193426

Blew, P., Muir, J. G., & Naik, V. N. (2010). The evolving Royal College examination in anesthesiology. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie, 57(9), 804-810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-010-9341-1

Blumberg, M., & Pringle, C. D. (1982). The missing opportunity in organizational research: Some implications for a theory of work performance. The Academy of Management Review, 7(4), 560–569. https://doi.org/10.2307/257222

Cook, D. A., & Steinert, Y. (2013). Online learning for faculty development: A review of the literature. Medical Teacher, 35(11), 930–937. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.827328

Daniel, C. M. (2014). Comparing online and face-to-face professional development [Doctoral dissertation, Nova Southeastern University]. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3157.5042

Feldman, M., Lazzara, E. H., Vanderbilt, A. A., & DiazGranados, D. (2012). Rater training to support high-stakes simulation-based assessments. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 32(4), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21156

Holmboe, E. S., Ward, D. S., Reznick, R. K., Katsufrakis, P. J., Leslie, K. M., Patel, V. L., Ray, D. D., & Nelson, E. A. (2011). Faculty development in assessment: The missing link in competency-based medical education. Academic Medicine, 86(4), 460–467. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cb2a7

Iqbal, I., Naqvi, S., Abeysundara, L., & Narula, A. (2010). The value of oral assessments: A review. The Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 92(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1308/147363510×511030

Juul, D., Yudkowsky, R., & Tekian, A. (2019). Oral Examinations. In R. Yudkowsky, Y. S. Park, & S. M. Downing (Eds.), Assessment in Health Professions Education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315166902-8

Kemp, N., & Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates’ opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

Khera, N., Davies, H., Davies, H., Lissauer, T., Skuse, D., Wakeford, R., & Stroobant, J. (2005). How should paediatric examiners be trained? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 90(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2004.055103

Lineberry, M. (2019). Validity and quality. Assessment in Health Professions Education, 17-32. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315166902-2

Marin-Garcia, J. A., & Martinez Tomas, J. (2016). Deconstructing AMO framework: A systematic review. Intangible Capital, 12(4), 1040. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.838

McLean, M., Cilliers, F., & Van Wyk, J. M. (2008). Faculty development: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Medical Teacher, 30(6), 555–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802109834

Md Hashim, N. H. (2021). Pre- and Post-test [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20186582.v1

Md Hashim, N. H. (2022). Followup Questionnaire [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20186591.v2

Newman, L. R., Brodsky, D., Jones, R. N., Schwartzstein, R. M., Atkins, K. M., & Roberts, D. H. (2016). Frame-of-reference training: Establishing reliable assessment of teaching effectiveness. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 36(3), 206–210. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000086

Newstrom, J. W. (1995). Evaluating training programs: The four levels, by Donald L. Kirkpatrick. (1994). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. 229 pp., $32.95 cloth. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 6(3), 317-320. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.3920060310

Singh, J., Evans, E., Reed, A., Karch, L., Qualey, K., Singh, L., & Wiersma, H. (2022). Online, hybrid, and face-to-face learning through the eyes of faculty, students, administrators, and instructional designers: Lessons learned and directions for the post-vaccine and post-pandemic/COVID-19 World. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 50(3), 301–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472395211063754

Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Anderson, B., Barnett, B. M., Centeno, A., Naismith, L., Prideaux, D., Spencer, J., Tullo, E., Viggiano, T., Ward, H., & Dolmans, D. (2016). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to enhance teaching effectiveness: A 10-year update: BEME Guide No. 40. Medical Teacher, 38(8), 769-786. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2016.1181851

Steinert, Y., Mann, K., Centeno, A., Dolmans, D., Spencer, J., Gelula, M., & Prideaux, D. (2006). A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Medical Teacher, 28(6), 497–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600902976

Tan, C. P. L., & Pallath, V. (2022). Workshop Evaluation Form [Dataset]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20189309.v1

Tekian, A., & Norcini, J. J. (2016). Faculty development in assessment : What the faculty need to know and do. In M. Mentkowski, P.F. Wimmers (Eds.), Assessing Competence in Professional Performance across Disciplines and Professions (1st ed., pp. 355–374). Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30064-1

Thomas, P. A., Kern, D. E., Hughes, M. T., & Chen, B. Y. (2015). Curriculum development for medical education : A six-step approach. John Hopkins University Press. https://jhu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/curriculum-development-for-medical-education-a-six-step-approach

Vollenbroek, W. B. (2019). Communities of Practice: Beyond the Hype – Analysing the Developments in Communities of Practice at Work [Doctoral dissertation, University of Twente]. https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789036548205

Williams, R. G., Klamen, D. A., & McGaghie, W. C. (2003). SPECIAL ARTICLE: Cognitive, social and environmental sources of bias in clinical performance ratings. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 15(4), 270–292. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1504_11

*Shairil Rahayu Ruslan

50604, Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia

03-79492052 / 012-3291074

Email: shairilrahayu@gmail.com, shairil@ummc.edu.my

Submitted: 23 August 2022

Accepted: 3 January 2023

Published online: 4 July, TAPS 2023, 8(3), 15-25

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2023-8-3/OA2871

Iroro Enameguolo Yarhere1, Tudor Chinnah2 & Uche Chineze3

1Department of Paediatrics, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria; 2Department of Anatomy, University of Exeter, United Kingdom; 3Department of Education and Curriculum studies, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Abstract

Introduction: This study aimed to compare the paediatric endocrinology curriculum across Southern Nigeria medical schools, using reports from learners. It also checked the learners’ perceptions about different learning patterns and competency in some expected core skills.

Methods: This mixed (quantitative and qualitative) study was conducted with 7 medical schools in Southern Nigeria. A multi-staged randomized selection of schools and respondents, was adopted for a focus group discussion (FGD), and the information derived was used to develop a semi-structured questionnaire, which 314 doctors submitted. The FGD discussed rotation patterns, completion rates of topics and perceptions for some skills. These themes were included in the forms for general survey, and Likert scale was used to assess competency in skills. Data generated was analysed using statistical package for social sciences, SPSS 24, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant

Results: Lectures and topics had various completion rates, 42.6% – 98%, highest being “diabetes mellitus”. Endocrinology rotation was completed by 58.6% of respondents, and 58 – 78 % perceived competency in growth measurement and charting. Significantly more learners, 46.6% who had staggered posting got correct matching of Tanner staging, versus learners who had block posting, 33.3%, p = 0.018.

Conclusion: Respondents reported high variability in the implementation of the recommended guidelines for paediatric endocrinology curriculum between schools in Southern Nigeria. Variabilities were in the courses’ completion, learners’ skills exposure and how much hands-on were allowed in various skills acquisitions. This variability will hamper the core objectives of human capital development should the trend continue.

Keywords: Paediatric Endocrinology Curriculum, Perception, Compliance, Completion Rate, Learners

Practice Highlights

- Medical and dental council of Nigeria has a recommended benchmark for minimum academic standards in all medical schools to which total compliance is expected.

- Evaluation of paediatric endocrinology curriculum content and training methods was conducted using reports from learners.

- Variability in the content, and training methods of the intended competency were reported across medical schools.

- Compliance rate of the recommended curriculum was less than 50% in some contents and some learners reported low skill performance training.

- The lack of uniformity can prevent achievement of the overarching objective of the curriculum in Nigeria with wide variations in competence among graduating doctors.

I. INTRODUCTION

The primary aim of the Medical and Dental council of Nigeria (MDCN) undergraduate curriculum is “to train doctors and dentists who can work effectively in a health team to provide comprehensive health care to individuals in any community in the nation, and keep up to date on issues of global health” (Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria, 2012). In Nigeria today, there are 49 federal, 59 states and 111 private universities, and 44 of these have full or partially accredited medical schools and while these schools have a prescribed curriculum, some are not following explicitly (Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria, 2012). This curriculum advocates for universities to develop syllabus to meet the benchmark for minimum academic standards (BMAS) across schools, however there is no uniform template developed for assessing graduates to know how their competence converge as is applicable in United States of America (USA), Canada and United Kingdom (UK) (Santen et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2020; Sosna et al., 2021). Diabetes mellitus, thyroid disorders, puberty, rickets and growth abnormalities are topics included in the MDCN paediatric curriculum under endocrinology which learners are expected to acquire competence in cognitive and psychomotor skills to diagnose and treat or refer appropriately children presenting with these diseases.

A. Problem

Most deaths from diseases in Nigeria and other resource-limited countries are consequent upon general public ignorance of disease, late presentation to the health care systems, poverty and lack of funds to access healthcare facilities and reduced knowledge of some disease patterns by the healthcare providers (Yarhere & Nte, 2018). Addressing the gaps in reduced knowledge can be done by developing competency-based curriculum for all graduating doctors to have as near-similar competence as possible but achieving this may not be feasible. Training activities are not uniform throughout medical schools in Nigeria and elsewhere, and depend on schools’ vision, mission and objectives, and the structures and processes put in place. There are barriers to positive implementation across schools including but not limited to individual school’s determination of what is relevant in the curriculum, access to the materials needed to teach the curriculum content and getting trainers to use these curriculums (Polikoff, 2018). The lack of uniformity of curriculum across universities may not be contending issues, but when the graduating doctors have varying degree of competencies in skills and cognition, then a template for imparting uniform and up to date knowledge and to evaluate this is needed to find ways of reducing the variability (McManus, 2003; McManus et al., 2020; Rimmer, 2014).

The curriculum uniformity across schools is one way of improving competency and thus, healthcare standards, and there is need to explore this uniformity or diversity within the paediatric undergraduate training. In some countries, there is a uniform board certification examination before doctors can practice and this is also done for doctors immigrating into these countries (Hohmann & Tetsworth, 2018; Puri et al., 2021; Tiffin et al., 2017; van Zanten et al., 2022) but Nigeria is exempt from this uniform exit examination. This uniform exit board examination makes these schools align course contents, and therefore reduces the variabilities between medical schools and undergraduate training.

B. Curriculum Evaluation for Change or Improvement

Curriculum evaluation is a means by which educators understand whether the curriculum used to train learners is working as intended, and whether there is need to change the entire programme or redesign aspects (Burton & McDonald, 2001; Ornstein & Hunkins, 2009). It is also a way of identifying deficiencies in training syllabus across universities, (Rufai et al., 2016) or whether compliance to a curriculum is being achieved (Grant, 2014; Olson et al., 2000). Kirkpatrick’s curriculum evaluation method is widely acceptable in medical education using the 4 steps; learners’ reaction or satisfaction, knowledge, behavioural changes and results or impact, and in Nigeria, for paediatric endocrinology, this has not been done (Alsalamah, 2021; Bates, 2004).

Universities have variabilities in organisation, students’ numbers in classes, duration of specific posting, posting types and whether the courses are elective or core. In medical schools in Nigeria, paediatric postings are undertaken in the 5th or 6th year of a 6-year programme. While some stagger the posting to be done within the last 2 years, others do theirs in the 5th or the 6th year exclusively, and the extent of these variabilities and how they affect the training processes and products has not been evaluated in Nigeria and this can be done using learners’ or graduates’ perceptions.

The aim of this research was to evaluate learners’ report and perception of some aspects of the paediatric endocrinology curriculum contents and learning methods across Southern Nigeria medical schools. Endocrinology was taken from the paediatric course to reduce the volume of information to be analysed.

II. METHODS

This was a cross sectional study design with qualitative and quantitative data analyses, evaluating learners’ report and their perception of the curriculum being used by various medical schools in Southern Nigeria to deliver the MDCN paediatric endocrinology curriculum. Survey was conducted across 10 medical schools in Southern Nigeria that have learners who have either completed their final year, or are doing their internship. Two steps were used to retrieve the information needed; a focus group discussion of sampled learners, and a questionnaire survey sent out to randomly selected respondents and these 2 methods complemented each other. The focus group discussion was used to explore in depth, the minds of the respondents and what they perceived was being done well and what needed to be changed in the syllabus in their respective schools. The questionnaire survey was then used to collect reports and perceptions from a wider set of learners who had completed their paediatric posting within the past 6 – 12 months. Some of these were already doing their internship and others were in their final year in preparation for their final examinations.

Sample size for respondents will be calculated using the formula:

N = (Z score)2 x SD x (1 – SD)

(CI)2

Z score = 1.96, SD (standard deviation of the mean) = estimated at ± 0.5, Confidence interval = 0.05

= 384 respondents, with an attrition rate of 10% will be added 10% of 384 = 38

384 + 38 = 422 respondents.

A. Sampling Technique

Multi-staged sampling technique was used to determine the schools, and respondents that participated in the study. There are 29 Southern Universities with medical / health colleges and 16 of these had more than 50 learners in their final year or had graduated. Ten schools were randomly selected using the excel formula [= rand ()], and a proportionate stratified sampling was done using the matriculation numbers of the students in each school to arrive at 422 respondents. Total number of learners that studied paediatrics in various institutions was 800; Ibadan 150, Port Harcourt, 128, Lagos 128, Niger delta University 69, UNN Enugu 128, University of Benin 128, Others 69. From the total number of learners in each school, selected learners and interns were sent the questionnaire using their email addresses. Selection for the FGD was done using simple random sampling from each school and these were sent separate emails with details for the meeting.

B. Focus Group Discussions Process

Focus group discussion was conducted with the respondents using zoom video platform, and the process lasted for 2 hours, 30 minutes. Ten learners’ representatives from the selected schools were contacted for this FGD, however, 7 (70%) agreed to participate after several email reminders. The interview was semi-structured with a flexible topic guide, which covered issues relating to the respondents’ views and opinions on the curriculum in paediatric endocrinology; description of posting type in each school, whether block, or staggered, topics received and/or completed, perception of their competence in a key psychomotor skill. The focus group interview discussions were recorded in the zoom meeting platform and transcribed verbatim. The data were analysed using the thematic framework content analyses method. The themes generated were categorised into; 1. Lecture contents and completion rate, 2. Types of paediatric rotation and posting, 3. Skill competence acquisition and clinical postings. Their perceptions about these themes were also sought and discussed. The transcription of the groups’ discussions was reviewed by IY and TC to help categorise the data and pull-out important quotes used.

C. Questionnaire Survey

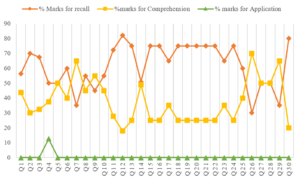

Following thematic analyses of the FGD, the themes generated were converted to questions in a survey for a larger sample population. Themes generated were the type of paediatric posting, rotations through units in the departments and paediatric endocrinology topics, training methods and competency acquired. Demographic characteristics of responders such as level/year of study, age, gender and university of study were collected. The respondents were also asked to select topics from a poll, included in their paediatric endocrinology syllabus, with result in Figure 1, and to state the various methods used to learn growth and growth disorders in their schools. A means of assessing cognitive (recall) skills of the learners was conducted using animated pictures of Tanner staging and matching-type multiple choice, and the responses were crossmatched with the type of posting learners were exposed to, i.e. block posting or staggered posting. Tanner staging was chosen as it cuts across general paediatrics and endocrinology as part of growth and puberty (endocrinology).

Data retrieved were analysed statistically by using chi-square test, and Pearson correlation for categorical variables. The level of competence perceived by learners in height measurement and charting on growth chart was retrieved using 5-point Likert scale (where 1 = not competent; 2 = low competence; 3 = neutral; 4 = competent; and 5 = proficient). The association between level of competence and whether learners rotated through paediatric endocrinology was checked using Pearson’s correlation test. For all statistics, p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

D. Ethics

The research commenced after the Research Ethics committee of the University of Port Harcourt granted approval (UPH/CEREMAD/REC/MM80/056). Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants during the focus group discussion, who also gave consent for video and recording of the process. Informed consent was also obtained from all participants who filled and submitted the online survey. The focus group discussants received N3,000 ($10) for internet data only as monetary compensation.

III. RESULTS

There were 314 learners from the 422 calculated sample size, responded to the questionnaire survey, giving a response rate of 74.4%. There were more final year respondents than early career doctors and more of the respondents were in the age bracket 20 – 24 years, with a mean of 25.02 ±2.71 years. The male: female ratio was 1:1.01, and the data that support the findings of this study are available in Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084 /m9.figshare.20730937.v1 (Yarhere et al., 2022).

|

RESPONDENTS |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Year of study |

|

|

|

|

Early career doctor (graduate/intern) |

130 |

41.4 |

p = 0.002 |

|

Final year |

184 |

58.6 |

|

|

University attended (calculated cohort) |

|

|

|

|

University of Port Harcourt (63) |

62 |

19.7 |

|

|

Niger Delta University (54) |

54 |

17.2 |

|

|

University of Ibadan (76) |

50 |

15.9 |

|

|

University of Benin (65) |

44 |

14.0 |

|

|

University of Lagos (65) |

40 |

12.7 |

|

|

University of Nigeria (65) |

42 |

13.4 |

|

|

Other western Universities (34) |

22 |

7.0 |

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

20-24 |

140 |

44.6 |

|

|

25-29 |

162 |

51.6 |

|

|

>=30 |

12 |

3.8 |

|

|

Mean |

25.02 ± 2.71 |

|

|

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

Male |

152 |

48.4 |

p = 0.612 |

|

Female |

162 |

51.6 |

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of all respondents and the universities attended

A. Evaluating Contents of Lecture Topics and Completion of Lectures

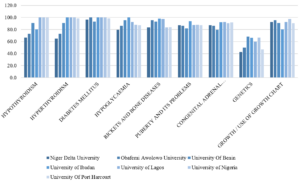

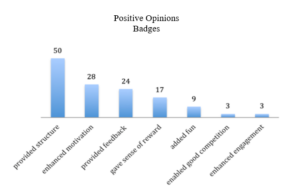

The syllabus lecturers use to teach courses are supposed to be descriptive with all learning outcomes stated in the handbook or in the log books given to them before the start of the academic year. The prescribed topics for paediatric endocrinology as stated below were not completely taught to learners or learners did not attend the lectures. In the discussion, some agreed that they did not have the full complement of lectures suggested by the BMAS. One respondent said she and her group mates did not receive diabetes mellitus lectures in their final paediatric posting. This fact was corroborated in the questionnaire survey as 2% of the respondents revealed not having diabetes mellitus lectures, and more than 40% did not learn genetics in their paediatric endocrinology training as shown in Figure 1.

Diabetes had almost 100% lecture recipient while genetic had the least. In some schools, genetics were placed under endocrine disorders while in others, genetics were left for the pathology and basic medicine classes.

“I was taught, I personally received 4 lectures in Paed Endo including ambiguous genitalia, “CAH” congenital adrenal hyperplasia, hypothyroidism, and puberty.”

Participant 3

“So, you did not get to do calcium and rickets?”

Facilitator

“No, I was not taught calcium and rickets.”

Participant 3

“What about growth and short stature?”

Facilitator

“Yes, I received introductory lectures in my young (sic), junior posting, yes I did in my 400 level, but not in my senior posting and it was not part of endocrinology but general paediatrics.”

Participant 3

“I did not take lectures in diabetes mellitus because it was rescheduled several times until we finally had to sit for our exams. In the end, many of us just took notes from our seniors and other students who had theirs when it was scheduled.”

Participant 2

“Why were the classes rescheduled? I mean what did the lecturer tell you?”

Facilitator

“The lecturer kept traveling or was indisposed most of our time in the senior posting.”

Participant 2

Participant 4 shared:

Dr. xxxxxx taught us diabetes mellitus and the topic was quite extensive. We learnt the different types, pathophysiology, aetiology, DKA, precipitating factors, risk factors, management. Our lecturers even made us do presentations on DKA, we monitored patients that were being managed for DKA, checking their urine samples for ketones, glucose and their blood pressure.

Figure 1: Percentage of learners in various schools who received/attended specific endocrinology lectures in their universities

B. Types of Paediatric Posting and Rotation and Perception of Learners Relating to Task Completion

There were basically 2 modes of paediatric posting in the institutions sampled; 4-months block posting where respondents have a month of didactic lectures and 3 months of clinical rotations through various units in the Paediatric departments, and 4 months of staggered rotations with junior and senior postings in the clinical classes. While some learners rotated through all the units (core and electives) in the departments, some went through core units, emergency and neonatal units, and 2 other units randomly selected for the respondents by the departments.

C. Learners’ Responses to Rotation through Paediatrics and Posting Types

Participant 2 shared:

The way it works in University of xxxx, we rotate through 2 elective postings with core (CHEW and SCBU) postings in the junior and senior postings. These elective postings are randomly selected by the department (meaning heads or coordinators). I did neurology and gastroenterology in my junior posting and haemato-oncology and I really can’t remember the other one in my senior posting.

“Will I be wrong to say you did not see a patient with Diabetic keto acidosis?”

Facilitator

“I saw a child with diabetic keto acidosis in the ward but it wasn’t my unit managing the patient. I only went to the ward to do some other thing.”

Participant 2

“If you were given the opportunity to design a curriculum or programme for your university, will you prefer what is being practiced now, or will you rather have every student go through every unit and get titbits from each unit?”

Facilitator

Participant 2 responded:

Yes, I will prefer that situation where you get to be exposed to every unit in the department but …. emmm, that creates a problem because you may be in a unit for a week, and no patient comes in but the next group rotating to the unit gets to see many patients. I would want to suggest that perhaps, instead of focusing on more of clinical posting, that a unified tutorial class which will expose everyone to the core diseases in the various disciplines.

Table 2 corroborates the information given by the focus group discussants. Testing the competency outcome in either method can give some estimated guess as to which is better, however, there are several confounding factors that will not allow fair comparison (See Table 3).

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

|

Paediatric posting in your university |

|

|

|

|

Staggered posting into Junior and senior paediatrics |

176 |

56.1 |

c2 = 4.59, |

|

Block posting of 4 months total |

138 |

43.9 |

p = 0.032 |

|

Paediatric rotations through various units in universities |

|

|

|

|

I rotated through all units in the department |

162 |

51.6 |

c2 = 0.318, |

|

I rotated through CHEW, neonatal unit, and 2/3 other units |

152 |

48.4 |

p = 0.573 |

|

Rotate through paediatric endocrinology unit in your university |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

184 |

58.6 |

c2 = 7.48, |

|

No |

130 |

41.4 |

p = 0.006 |

Table 2. Paediatric posting and unit rotations in the departments (n=314)

Though there were differences in the mode of paediatric postings where staggered or block, c2 = 4.59, p = 0.032. the difference in proportion of respondents who had core and selected elective posting as against all units posting was not significant, c2 = 0.318, p = 0.573.

|

|

Block posting of 4 months |

Staggered junior and senior paediatrics |

|

|

Correct |

Count |

46 |

82 |

|

% within paediatric posting |

33.3% |

46.6% |

|

|

% of Total |

14.6% |

26.1% |

|

|

Wrong |

Count |

92 |

94 |

|

% within paediatric posting |

66.7% |

53.4% |

|

|

% of Total |

29.3% |

29.9% |

|

|

Total |

Count |

138 |

176 |

|

% within correct response |

43.9% |

56.1% |

|

|

% of Total |

43.9% |

56.1% |

|

Table 3: Comparing correct response to animated picture of Tanner stage (pubic hair) in females, and the type of paediatric rotation learners were exposed to

In the 2×2 table above where recall was tested in the learners based on their paediatric posting type, higher percentage of those who had staggered posting got the correct matching of Tanner stage, and the difference was significant, c2 = 5.630, p = 0.018. However, the total number of respondents with the correct response was low.

D. Perception of Core Competency Skill in Growth Measurement and Charting by Learners

One of the most important courses in paediatrics is growth and development and training future medical doctor to acquire skills and competence in growth and management is a key component of the BMAS. While growth measurement may seem easy to the uninformed, the whole task is daunting especially in children with complex growth abnormalities and malformation, and for more complex skills like arm span. Which of the more complex skills should the learner be expected to be competent in, will be debated in an expert forum of trainers.

“So, did you do anthropometric measures?”

Facilitator

Participant 1 shared:

Yes, anytime we clerk a patient, we must check the weight and height and interpret using age-appropriate charts, but we did not plot them in the charts. We carry the age-appropriate chart and interpreted our patients, as this is a requirement.

Using the chart may not be emphasised by all paediatric lecturers, so learners can be smart to know those lecturers who will request this skill from them during the clerkship period or the unit rotations.

“We did not quite get the concept of mid parental height, height percentile, it was just mentioned in passing. I never saw a severely short child that needed growth hormone. I was only told by a classmate of mine.”

Participant 3

The charting and interpretation of weight and height measurements of children was not done in all schools as shown in Table 4 below, which tells that only 65.8% of total respondents were taught interpretation of measured and charted growth parameters. The level of competence in these tasks will also be varied as seen in Appendix 1. Two hundred and thirty-eight (75.8%) learners perceived they had competency/ proficiency in height measures using stadiometer, and 44.6 % of the learners with these perceptions actually had paediatric endocrinology clinical rotation (Appendix 1).

|

Variable |

Frequency n = 314 |

Percent (%) |

|

How was growth and growth disorders taught in your school (Multiple response applicable) |

|

|

|

Didactic lectures |

272 |

86.6 |

|

Measurement of children using standardised stadiometer |

230 |

73.2 |

|

Charting of growth measurements in CDC/WHO growth charts |

203 |

64.6 |

|

Measurement of children using improvised height rules |

157 |

50.0 |

|

Interpretation of measured and charted growth parameters |

203 |

64.6 |

|

Ward clerkship and presentation |

230 |

73.2 |

|

Measurements of children using bathroom spring balance |

140 |

44.6 |

|

Use of bone age X radiographs |

78 |

24.8 |

|

Use of orchidometer |

90 |

28.6 |

Table 4: Methods used to teach growth and growth disorders in various institutions

Bone age and orchidometers are used to assess skeletal maturation and puberty, which are advanced for the undergraduate learners and certainly not compulsory, but some respondents were taught with the tools showing the variabilities in contents and skills delivery between these schools. From Table 4 above, framers of the syllabus for endocrinology aspect of paediatrics curriculum are unlikely to include use of orchidometer and bone age during the undergraduate paediatric endocrinology rotation as the skill is complex, and not necessary for their level of development.

IV. DISCUSSION

This study has highlighted differences in course contents and training methods across medical schools in Southern Nigeria. While many schools have used the BMAS prescribed by the MDCN, the syllabus used are different and the intended learning outcomes are diverse based on the respondents’ reports. Some learners reported not having diabetes lectures in their school through no fault of theirs, as lecturer rescheduled the lectures and never gave them. While learners have the responsibility to attend lectures, trainers are also obligated to be present at their scheduled lectures or transfer this to their teacher-assistants, or use technologies (Grant, 2014; Ruiz et al., 2006). Some learners had little participation in the Emergency Room, others participated fully in DKA management, learning empathy, specialised skills and communication. The intended competencies to be acquired can be achieved through shadowing and participation, bed-side teaching, and tutorial to improve the cognitive and psychomotor skill, and these opportunities must be created for them in experiential settings (Ryan et al., 2020; Shah et al., 2020).

More learners had staggered postings, going through junior and senior paediatric postings in what may be considered as integrated learning departing from the traditional method (Patel et al., 2005; Watmough et al., 2006, 2009). In the staggered posting type of rotation, we noticed that not all learners went through paediatric endocrinology unit posting, and like one of the discussants said, they would rather everyone went through each unit getting bits of everything and having opportunity to study specific and prevalent diseases in paediatric units rather than leaving them with the possibility of not learning important disorders. As it is not always possible to encounter specific diseases like DKA during entire posting in the schools that use staggered posting types, the likelihood of exposure was higher in schools that had block posting from the FGD conducted, but this did not translate to better retention of skills or cognitions as depicted in the Tanner staging matching question.

Having learners train in all special postings may not be the best approach in undergraduate medicine because the specialised skills may not be utilised in general practice and even in general paediatrics should the learners plan paediatric specialisation (Bindal et al., 2011). While some trainers may argue that all information and skill should be taught to the learners, the time to acquire and achieve mastery may be short for the learners (Jensen et al., 2018; Offiah et al., 2019). This study can be referenced in curriculum designing and implementation so the framers understand what society needs should be filled at any time. The concept of cognitive overload has actually reduced the duration of core specialty in clinical medicine while increasing the duration for others with emphasis on psychomotor, affective skills and professionalism. Some medical schools have core paediatric posting of 7 – 8 weeks, but Nigeria is still fixed with the traditional 3 – 4 months. In some schools in South Africa, the clinical posting is run as modular block for 3 years, with paediatric curriculum running from year 4 through year 6 (Dudley & Rohwer, 2015). With the long duration in the Nigeria curriculum, skills competencies are still deficient, so there is need to revamp the curriculum to make it more competency driven. It is excusable that more sophisticated competence like use of orchidometer were not known by more than half the learners, but if some were taught, the level of confidence in these skills at this stage of their learning should also be assessed as was done for diabetes by George et al. (2008).

Medical schools in Nigeria and other countries will have to continually evolve and produce curricula that are competency based, using problem-based learning, simulations, mannikin training for skills as is done in other countries (Watmough et al., 2006). Diabetes, thyroid, ambiguous genitalia with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, short stature and calcium disorders are common in Nigeria and should be taught in structured and integrated formats. Integrated curriculum where skills are graded from simple to complex can also be tested e g, skills of height measurements and charting using the stadiometer and growth charts can be taught in the 1st clinical year, and then the mid parental heights, target height calculation and bone age may be taught in the 2nd and 3rd clinical years. (Brauer & Ferguson, 2015; Grant, 2014).

A. Strength of the Research

Articulating the perceptions of learners is not always easy as they are varied and subjective, but getting them to come together, discuss and give suggestions on how curriculum can be designed and achieved increases the strength of this research. There was no sense of victimisation of the learners as many had already graduated from their schools, and the discussants admitted to not missing classes, or clinical learning. They spoke freely, with courtesy to others and there was little or no argument among them.

B. Limitations of the Research

As this research is based on past experiences of the cognitive and psychomotor skills achieved during the learners’ training period, the possibility of recall bias is high, and respondents may underestimate or exaggerate their skills. Using respondents who had just concluded their paediatric postings was an attempt at reducing this limitation. The best time to evaluate a programme is usually soon after the programme has been concluded however, as there has been no report of this type of evaluation, there was need to embark on it and make recommendations.

V. CONCLUSION

Respondents reported high variability in the implementation of the recommended guidelines for paediatric endocrinology curriculum between schools in Southern Nigeria. Variabilities were in the courses’ completion, learners’ skills exposure and how much hands-on were allowed in various skills acquisitions. This variability will hamper the core objectives of human capital development should the trend continue.

A. Area of Future Research

Noting the differences exist between schools, curriculum strategists and implementation teams in universities should commission a DELPHI study by experts, where core competencies and objectives for paediatric endocrinology will be agreed on and sent to the regulatory bodies for endorsement and implementation.

Notes on Contributors

IY conceived, designed, planned, executed and conducted interviews and the research. He also collected the data, analysed it and wrote the manuscript.

TC helped in designing the methodology for the data colllection and analyses, and reviewed the manuscript.

CU gave critical appraisal of the manuscript and all authors have approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

The research ethics committee of the Univeristy of Port Harcourt gave ethical approval before the start of the study with the number: UPH/CEREMAD/REC/MM80/056.

Data Availability

The data supporting this research is available for publication purposes, without editing. Data can be shared only with express permission from the corresponding author as deposited in Figshare repository, using the private url:

https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Copy_of_CURRICULUM_STUDENTS_xls/21154396

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the early career doctors and final year students who participated in the online survey especially the selected ones who took part in the focus group discussion.

Declaration of Interest

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest, including financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

Funding

There was no funding for this survey.

References

Alsalamah, A., & Callinan, C. (2021). Adaptation of Kirkpatrick’s four level model of training criteria to evaluate training programmes for head teachers. Education Science, 11(116), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030116

Bates, R. (2004). A critical analysis of evaluation practice: The Kirkpatrick model and the principle of beneficence. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27, 341-347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.04.011

Bindal, T., Wall, D., & Goodyear, H. M. (2011). Medical students’ views on selecting paediatrics as a career choice. European Journal of Pediatrics, 170(9), 1193-1199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-011-1467-9

Brauer, D. G., & Ferguson, K. J. (2015). The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Medical Teacher, 37(4), 312-322. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.970998

Burton, J. L., & McDonald, S. (2001). Curriculum or syllabus: Which are we reforming? Medical Teacher, 23(2), 187-191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590020031110

Dudley, L. D., Young, T. N., Rohwer, A. C., Willems, B., Dramowski, A., Goliath, C., Mukinda, F. K., Marais, F., Mehtar, S., & Cameron, N. A. (2015). Fit for purpose? A review of a medical curriculum and its contribution to strengthening health systems in South Africa. African Journal Health Profession Education, 7(1), 81-84. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.512

Federal Ministry of Health of Nigeria, Health Systems 20/20Project. (2012). Nigeria undergraduate medical and dental curriculum template. Health systems 20/20 Project, Abt Associates Inc.

George, J. T., Warriner, D. A., Anthony, J., Rozario, K. S., Xavier, S., Jude, E. B., & Mckay, G. A. (2008). Training tomorrow’s doctors in diabetes: Self-reported confidence levels, practice and perceived training needs of post-graduate trainee doctors in the UK. A multi-centre survey. BMC Medical Education, 8, Article 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-8-22

Grant, J. (2014). Principles of curriculum design. In T. Swanwick, K. Forrest, B. C. O’Brien (Eds.), Understanding medical education evidence, theory and practice Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell, 31-46.

Hohmann, E., & Tetsworth, K. (2018). Fellowship exit examination in orthopaedic surgery in the commonwealth countries of Australia, UK, South Africa and Canada. Are they comparable and equivalent? A perspective on the requirements for medical migration. Medical Education Online, 23(1), Article 1537429. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2018.1537429

Jensen, J. K., Dyre, L., Jørgensen, M. E., Andreasen, L. A., & Tolsgaard, M. G. (2018). Simulation-based point-of-care ultrasound training: a matter of competency rather than volume. Acta Anaesthesiology Scandanavia, 62(6), 811-819. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.13083

McManus, I. C. (2003). Medical school differences: beneficial diversity or harmful deviations. BMJ Quality and Safety in Health Care, 12(5), 324-325. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.5.324

McManus, I. C., Harborne, A. C., Horsfall, H. L., Joseph, T., Smith, D. T., Marshall-Andon, T., Samuels, R., Kearsley, J. W., Abbas, N., Baig, H., Beecham, J., Benons, N., Caird, C., Clark, R., Cope, T., Coultas, J., Debenham, L., Douglas, S., Eldridge, J., . . . Devine, O. P. (2020). Exploring UK medical school differences: the MedDifs study of selection, teaching, student and F1 perceptions, postgraduate outcomes and fitness to practise. BMC Medicine, 18(1), Article 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01572-3

Offiah, G., Ekpotu, L. P., Murphy, S., Kane, D., Gordon, A., O’Sullivan, M., Sharifuddin, S. F., Hill, A. D. K., & Condron, C. M. (2019). Evaluation of medical student retention of clinical skills following simulation training. BMC Medical Education, 19(1), Article 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1663-2

Olson, A. L., Woodhead, J., Bekow, R., Kaufman, N., & Marshal, S. (2000). A national general pediatric clerkship curriculum: The process of development and implementation. Pediatrics, 160(S1), 216 -222. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.S1.216

Ornstein A, H. F., & Hunkins, F. P. (2009). Curriculum: Foundations, principles and issues (5th Ed.). Pearson.

Patel, V. L., Arocha, J. F., Chaudhari, S., Karlin, D. R., & Briedis, D. J. (2005). Knowledge integration and reasoning as a function of instruction in a hybrid medical curriculum. Journal of Dental Education, 69(11), 1186-1211. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16275683

Polikoff, M. S. (2018). The challenges of curriculum materials as a reform lever Evidence Speaks Reports, 2, 58

Puri, N., McCarthy, M., & Miller, B. (2021). Validity and reliability of pre-matriculation and institutional assessments in predicting USMLE STEP 1 success: Lessons from a traditional 2 x 2 curricular model. Frontiers in Medicine (Lausanne), 8, Article 798876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.798876

Rimmer, A. (2014). GMC will develop single exam for all medical graduates wishing to practise in UK. BMJ, 349, g5896. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g5896

Rufai, S. R., Holland, L. C., Dimovska, E. O., Bing Chuo, C., Tilley, S., & Ellis, H. (2016). A national survey of undergraduate suture and local anesthetic training in the United Kingdom. Journal of Surgical Education, 73(2), 181-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.09.017

Ruiz, J. G., Mintzer, M. J., & Leipzig, R. M. (2006). The impact of E-learning in medical education. Academic Medicine, 81(3), 207-212. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002

Ryan, A., Hatala, R., Brydges, R., & Molloy, E. (2020). Learning with patients, students, and peers: Continuing professional development in the solo practitioner workplace. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Profession, 40(4), 283-288. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000307

Santen, S. A., Feldman, M., Weir, S., Blondino, C., Rawls, M., & DiGiovanni, S. (2019). Developing comprehensive strategies to evaluate medical school curricula. Medical Science Educator, 29(1), 291-298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-00640-x

Shah, S., McCann, M., & Yu, C. (2020). Developing a national competency-based diabetes curriculum in undergraduate medical education: A Delphi study. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 44(1), 30-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2019.04.019

Sosna, J., Pyatigorskaya, N., Krestin, G., Denton, E., Stanislav, K., Morozov, S., Kumamaru, K. K., Jankharia, B., Mildenberger, P., Forster, B., Schouman-Clayes, E., Bradey, A., Akata, D., Brkljacic, B., Grassi, R., Plako, A., Papanagiotou, H., Maksimović, R., & Lexa, F. (2021). International survey on residency programs in radiology: similarities and differences among 17 countries. Clinical Imaging, 79, 230-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2021.05.011

Tiffin, P. A., Paton, L. W., Mwandigha, L. M., McLachlan, J. C., & Illing, J. (2017). Predicting fitness to practise events in international medical graduates who registered as UK doctors via the Professional and Linguistic Assessments Board (PLAB) system: a national cohort study. BMC Medicine, 15(1), Article 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0829-1

van Zanten, M., Boulet, J. R., & Shiffer, C. D. (2022). Making the grade: licensing examination performance by medical school accreditation status. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), Article 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03101-7

Watmough, S., Garden, A., & Taylor, D. (2006). Does a new integrated PBL curriculum with specific communication skills classes produce Pre Registration House Officers (PRHOs) with improved communication skills. Medical Teachers, 28(3), 264-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590600605173

Watmough, S., O’Sullivan, H., & Taylor, D. (2009). Graduates from a traditional medical curriculum evaluate the effectiveness of their medical curriculum through interviews. BMC Medical Education, 9, Article 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-9-64

Yarhere, I., Chinnah, T., & Uche, C. (2022). Learners’ report and perception of differences in undergraduate paediatric endocrinology curriculum content and delivery across Southern Nigeria. [Data set]. Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.20730937.v1