Can digital media affect the learning approach of medical students?

Published online: 2 January, TAPS 2019, 4(1), 13-23

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-1/OA1058

Sonali Prashant Chonkar1,2, Hester Lau Chang Qi2, Tam Cam Ha3, Melissa Lim2, Mor Jack Ng2 & Kok Hian Tan1,2,4,5,6

1Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore; 2Division of Obstetrics & Gynaecology (O&G), Kandang Kerbau Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH), Singapore; 3The University of Wollongong, Australia, 4SingHealth Duke-NUS Joint Office of Academic Medicine, Singapore; 5Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, NUS, Singapore; 6Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Abstract

Background: Students’ learning approaches have revealed that deep learning approach has a positive impact on academic performance. There are suggestions of a waning interest in deep learning to surface learning.

Aim: To assess if digital media can reduce the incidence of surface learning approach among medical students

Method: A digital video introducing three predominant learning approaches (deep, strategic, surface) was shown to medical students between March 2015 and January 2017. The Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST), was administered at the beginning and end of their clinical attachment, to determine if there were any changes to the predominant learning approaches. A survey was conducted using a 5-point Likert scale to assess if video resulted in change.

Results: Of 351 students, 191 (54.4%) adopted deep, 118 (33.6%) adopted strategic and 42 (12.0%) adopted surface as their predominant learning approach at the beginning of their clinical attachment. At the end of their clinical attachment, 171 (49.6%) adopted deep, 143 (41.4%) adopted strategic and 31 (9.0%) adopted surface learning as their predominant learning approach. The incidence of students predominantly using surface approach decreased from 42 (12.0%) to 31 (9.0%), although not statistically significant. Qualitative feedback from students stated that they were more likely to adopt non-surface learning approaches after viewing the video.

Conclusion: This evaluation highlighted the potential of digital media as an educational tool to help medical students reflect on their individual learning approaches and reduce the incidence of surface learning approach.

Keywords: Learning Approaches, ASSIST, Digital Media, Video, Deep Learning, Surface Learning

Practice Highlights

- Digital media can help educate the students about three learning approaches: deep learning, strategic learning and surface learning approach.

- Digital media can encourage students to reflect on their own predominant learning approach.

- Digital media has potential to reduce the medical students’ reliance on surface learning approach.

- Approaches to learning may be influenced by curriculum structure.

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical students are exposed to staggering amounts of information during their career and have to assimilate information, apply clinical reasoning and undertake high stakes assessments. Most schools however, do not concentrate so much on the way students comprehend this knowledge. The way a student learns is affected by how the student was taught, the policies of the department and school, and the student’s own learning style (Newble & Entwistle, 1986). It is an acquired trait dependent on the learning context (Entwistle, 1997). There is little effort employed by teachers to enhance the possibility that individual students will achieve their full potential. Studying students’ approach to learning thus becomes an important factor that can determine both the quality and quantity of students’ learning (Amini, Tajamul, Lotfi, & Karimian, 2012).

In the recent years, there is a greater shift in focus to explore students’ approach to learning, particularly on these three distinct learning approaches – deep, strategic and surface approaches (Subasinghe & Wanniachchi, 2009; Wickramasinghe & Samarasekera, 2011; Samarakoon, Fernando, & Rodrigo, 2013; Shankar, Balasubramanium, & Dwivedi, 2014; Reid, Evans, & Duvall, 2012; Shah et al., 2016; Shankar, Dubey, Binu, Subish, & Deshpande, 2005; Aaron & Skakun, 1999; Cebeci, Dane, Kaya, & Yigitoglu, 2013; Amini et al., 2012). Deep learners focus developing interest in ideas, on reflecting and making connections between related concepts, thereby gaining a more thorough understanding, as well as better retention of content. Strategic learners adopt a systematic manner of studying with overt emphasis on learning certain concepts to excel in assessments. However, there may not be adequate integration across the topics as compared to deep approach and learners sometimes lack conceptual understanding (Leite, Svinicki, & Shi, 2010). Surface learners memorise all the information with little or no conceptual understanding and as a result, often find little interest in the concepts learned and tend not to read beyond what is stated in the syllabus. They may also be poorly motivated and result in being ineffective learners with a low level of understanding. Trigwell and Prosser (1991) suggested a negative correlation between surface learning approach and quality of learning, and the opposite for deep learners. Subasinghe et al. (2011) concluded that the adoption of deep and strategic learning approach will be beneficial to medical students, since their learning involves critical analysis and application of concepts for complex clinical situations. They also found that students with deep approach tend to achieve higher performance and vice versa.

While it is comforting that majority of the medical students preferred deep and strategic learning approaches (Subasinghe & Wanniachchi, 2009; Shankar et al., 2014; Reid et al., 2012; Shankar et al., 2005), Amini et al., (2012) and Aaron and Skakun (1999) found their medical students were more inclined towards the surface learning approach. Cecebi et al. (2013) found that their third year medical students preferred surface learning compared to the first and second year, suggesting the possibility of a waning interest in the deep learning approach as students progress through medical school. Being aware of our medical students’ predominant learning approaches in order to shift them to move towards more effective learning approaches was an important endeavour.

In this age of advanced information technology, teaching methods have evolved to meet the opportunities and challenges in undergraduate medical education (S.O. Ekenze, Okafor, O. S. Ekenze, Nwosu, & Ezepue, 2017; Shelton, Corral, & Kyle 2017). Multimedia e-learning enhances both teaching and learning (Ruiz, Mintzer, & Leipzig, 2006). Videos are being utilised in higher education to deliver useful content that can engage students (Mitra, Lewin-Jones, Barrett, & Williamson, 2010). We used digital video as an intervention to engage our students to reflect on the three predominant learning approaches, so that they become aware of their own predominant learning approach and reassess their approach. The advantages of using a video is that it can be easily used in multiple locations, updates added as required, short time frame to deliver information and can be re-watched at any time convenient to the audience.

This study aimed (i) to evaluate the learning approaches of medical students in Singapore, (ii) to assess if a video digital media intervention is effective in introducing the idea of ‘surface’, ‘strategic’ and ‘deep’ learning approaches and whether any change in that approach resulted.

II. METHODS

A. Participants

The study population comprised 351 Singaporean medical students from SingHealth who attended the Obstetrics and Gynaecology (O&G) clinical rotation a SingHealth from March 2015 to January 2017.

B. Study Design

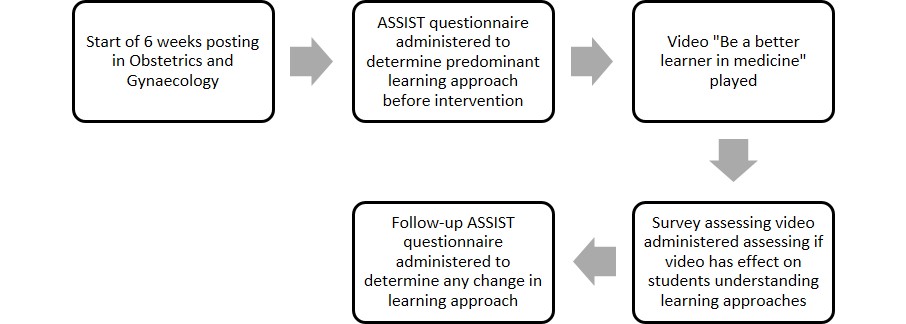

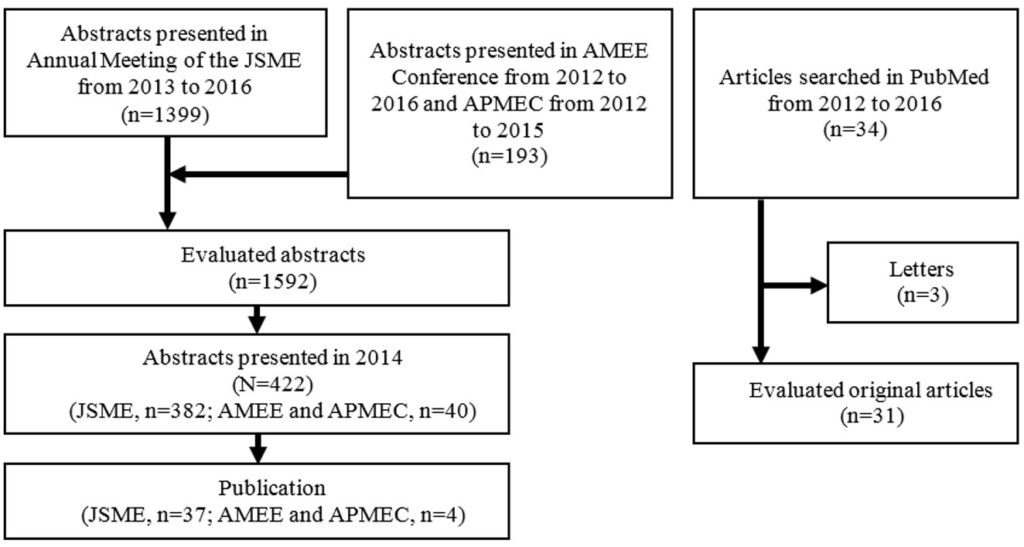

We used the Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST) questionnaire (see Appendix) to assess the students’ learning approaches at the beginning and the end of the students’ O&G posting in SingHealth (Figure 1).

The ASSIST questionnaire is a revised version of the Approaches to Studying Inventory (ASI), developed by Tait, Entwistle and McCune (1998). The questionnaire has been validated in various cultures globally, including amongst eastern cultural population such as Chinese university students and also across the western student population in Britain and Scotland (Gadelrab, 2011; Albedin, Jaarfar, Husain, & Abdullah, 2013). The ASSIST questionnaire comprises of 52 questions divided into 13 subscales of 4 questions. Each questions is scored on a five-point Likert scale (1 for “low” through 3 for “average” to 5 for “high”), with 16 questions pertaining to surface and deep learning each and 20 questions relating to strategic learning. An example of a question assessing deep approach is “I try to relate ideas I come across to those in other topics or other courses whenever possible.”; strategic approach is “I think I’m quite systematic and organised when it comes to revising for exams.”; and surface approach is “I find I have to concentrate on just memorising a good deal of what I have to learn.” The scores for sets of 4 were combined into 13 subscales and further grouped to give each respondent a score for deep, strategic and surface approach. The predominant learning approach is defined as the approach which has the highest mean score amongst the three approaches. The predominant learning approach is calculated based on the mean of the respective questions for each of the three learning approaches.

Figure 1. An illustration of the study design – Beginning with the administration of ASSIST questionnaire, to the video intervention and the follow-up ASSIST questionnaire again to determine any change in learning approach

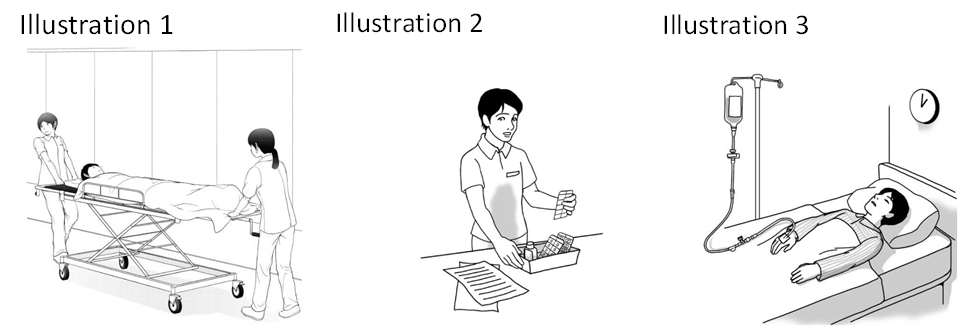

After completing the first questionnaire the same group of students were shown a video (Chonkar et al., 2018) entitled, “Be a better learner in medicine”, featuring three students. The video provided an introduction to three learning approaches and a description of these approaches. It then illustrated how learners adopting the three learning approaches would react and respond in three different scenarios in the context of learning the management of an high risk obstetrics condition: a normal tutorial, when studying in their own time and when being assessed during a test. As outlined by Rondon-Berrios and Johnston (2016), there are multiple techniques of successful teaching in a clinical environment including, role modelling and pattern recognition. The video capitalises on these two techniques to show how students who adopted these three different learning approaches would usually behave and illustrated the outcomes at the end of the video.

In the first scenario of the video, the student who adopted the surface learning approach decided to memorise information about the high-risk obstetric conditions from sources such as handbooks and lecture notes. There was no attempt to understand the basic pathophysiology of the condition or the underlying principle of management. The second student who adopted the strategic approach, used resources like important literature highlighted by the tutor and past year questions for targeted preparation to perform well in the final exam. There were attempts in clinical reasoning while managing the obstetric high risk condition. The student did not spend enough time to thoroughly understand underlying principles of management of medical disorder in pregnancy but rather selectively spent time studying selected topics which were deemed to be important. The deep learner went in depth to understand the basic pathophysiology and systematically approached the management with clinical reasoning with respect to stages of pregnancy that the patient could be in for that obstetric condition. The student further understood the critical aspect of the underlying principle of management of obstetric high risk conditions i.e. trying to balance the risks of prematurity due to early delivery versus the risks of continuing pregnancy endangering the mother and foetus, which can be applied to almost all other obstetric conditions. The student in the third scenario equipped herself by applying this underlying principle to other obstetric high-risk conditions when studying.

The final scene depicted the three students attempting their final posting examination. The surface learner experienced ‘brain freeze’ with clinical reasoning and was unable to remember the facts. The student adopting the strategic approach was able to apply some clinical reasoning to the question which she had previously identified to be important from examination point of view but did not do so well when another condition that was tested was not in her ‘radar screen’ of topics. The student who adopted the deep learning approach was able to apply correct clinical reasoning and underlying obstetrics principles to both obstetric conditions tested, even though one of the conditions was not familiar to her yet she was able to answer well. The video ended with a summary of the three learning approaches and the importance of adopting a non-surface learning approach to enhance learning and retention of knowledge.

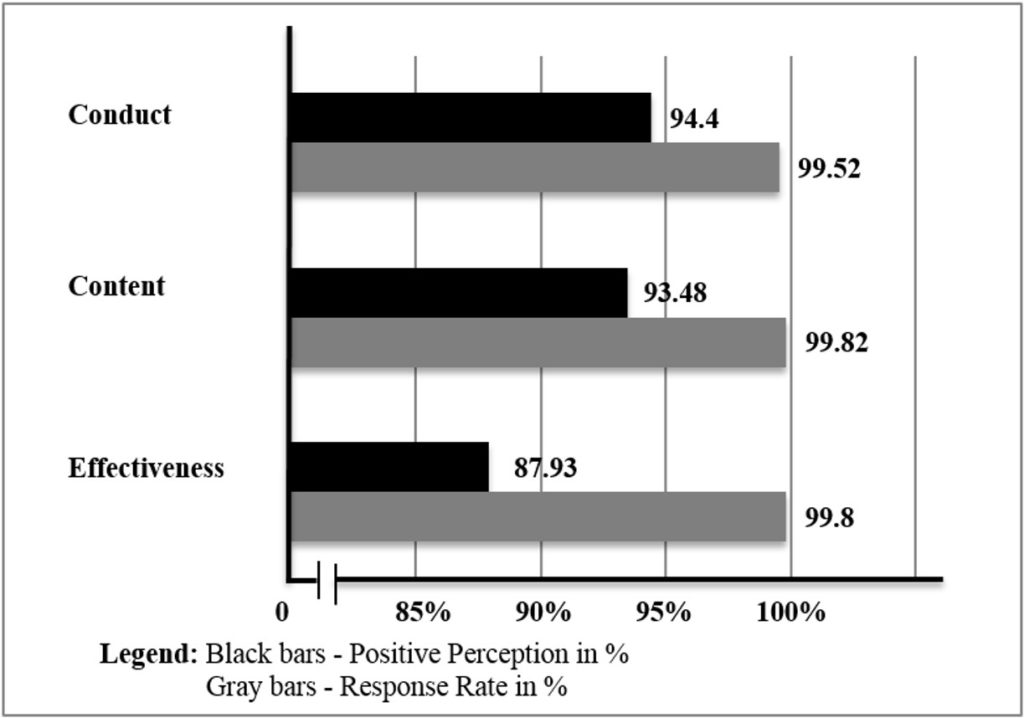

A survey containing five relevant questions was conducted with answers on a 5-point Likert scale to assess if video was effective in helping students understand the three learning approaches and reflect on their own approach. The survey explored if students were willing to change their learning approach to a more favourable one. Positive response was then defined as those responses that were rated a 4 or 5 (Agree/Strongly Agree), Neutral response was those rated as 3 and Negative response was those rated as 1 or 2 (Disagree/Strongly Disagree).

C. Statistical Analyses

The data were analysed using Microsoft Excel program and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Scores were aggregated pre- and post-intervention. The differences between the mean scores from ASSIST questionnaire administered pre- and post-intervention were analysed using Mann-Whitney test for standard deviation and p-value significance. Significant p-value was taken as p<0.05 in this study.

III. RESULTS

A total of 351 students completed the pre-video ASSIST questionnaire. Six students were unavailable to complete the ASSIST questionnaire at the end of the posting. The demographic characteristics of the 345 medical students are listed in Table 1.

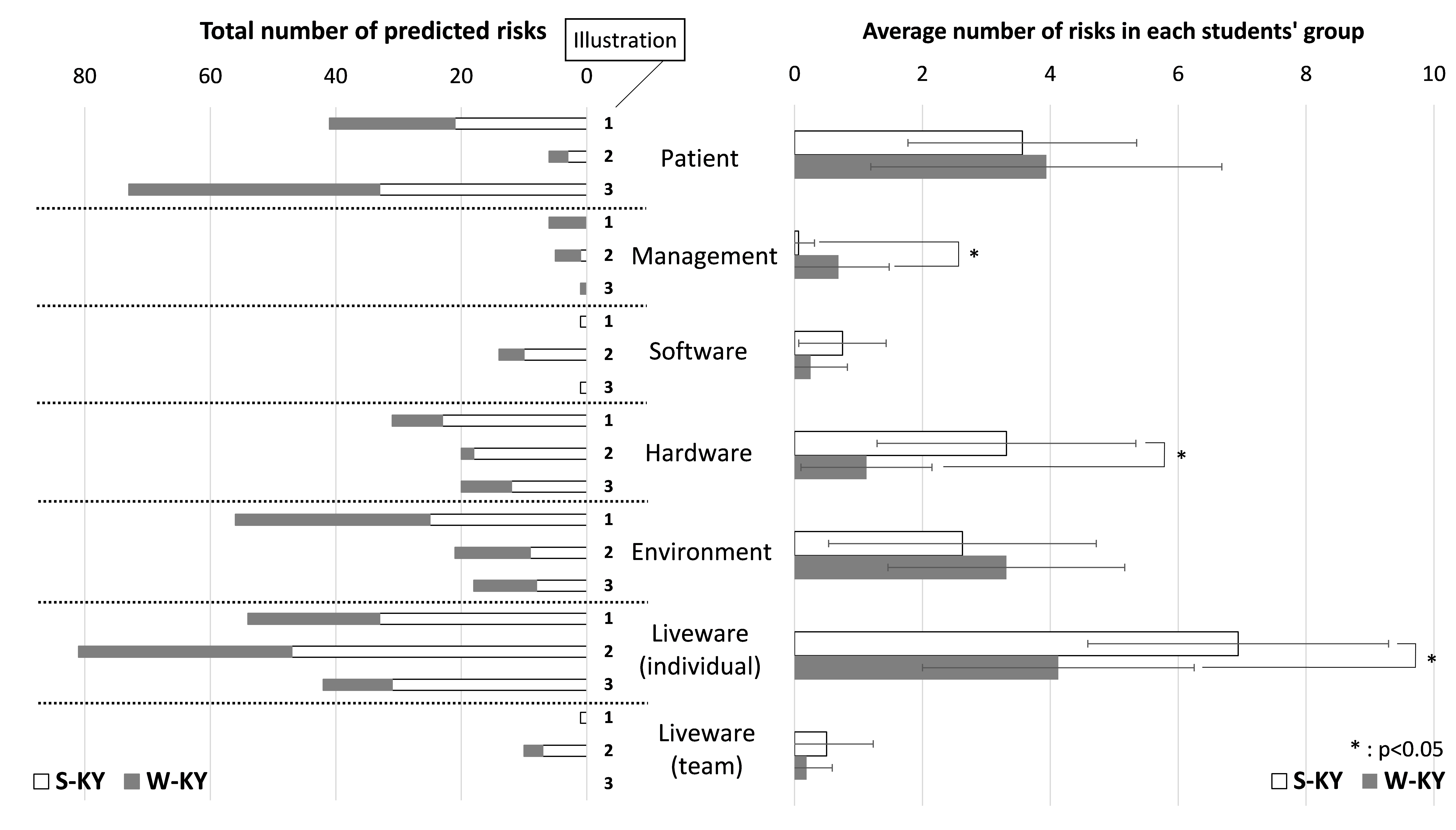

A. Type of Predominant Learning Approach Pre and post-video intervention

As seen in Table 2, more students adopted the deep learning approach prior to the beginning of the rotation (Deep 54.4% vs Surface 12.0% vs Strategic 33.6%). After 6-weeks of rotation in O&G, the strategic learners increased from 33.6% to 41.4%. The surface learners decreased from 12.0-9.0% and the deep learners decreased from 54.4% to 49.6%.

Further analysis of the pre- and post-intervention scores of the ASSIST questionnaire actually showed that only the increased in strategic learners was statistically significant. The decrease in the numbers of deep and surface learners was both statistically insignificant (Table 3).

| Characteristics of medical students | Numbers (%) |

| Total number of students | 345 |

| Average age , years (range) | 23 (21-35) |

| Sex | |

| – Male, n (%) | 152 (44.1) |

| – Female, n (%) | 193 (55.9) |

| Race | |

| – Chinese, n (%) | 314 (91.0) |

| – Non-Chinese, n (%) | 31 (9.0) |

| Nationality | |

| – Singaporean, n (%) | 316 (91.6) |

| – Non-Singaporean, n (%) | 29 (8.4) |

| Medical School | |

| – Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, n (%) | 275 (79.7) |

| – Duke-NUS, n (%) | 70 (20.3) |

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of medical students

| Predominant Learning Approach | No. of students at the beginning of rotation (%) | No. of students after 6-weeks rotation (%) |

| Surface | 42 (12.0) | 31 (9.0) |

| Strategic | 118 (33.6) | 143 (41.4) |

| Deep | 191 (54.4) | 171 (49.6) |

| Total no. of students | 351 | 345 |

Table 2. Predominant learning approach adopted by students at the beginning and the end of 6-weeks rotation

| Predominant learning approach | Mean score at the beginning of posting | Mean score at the end of posting | Standard deviation | p-value |

| Surface | 62.6 | 61.4 | 11.1-11.7 | 0.060 |

| Strategic | 72.7 | 74.6 | 9.94-11.0 | 0.014 |

| Deep | 74.8 | 75.9 | 8.9-10.8 | 0.120 |

Table 3. The change in of the mean aggregate scores of ASSIST questionnaire for the various predominant learning approaches at the beginning and the end of 6-weeks rotation, after the video intervention

| Video Survey Questions | Negative response

(%) |

Neutral

response (%) |

Positive response

(%) |

| The learning approaches explained in the video were clear | 1(0.3) | 19(7.0) | 249(92.0) |

| The video was engaging | 18(6.6) | 58(21.5) | 193(71.0) |

| The duration of the video was just right | 24(8.9) | 44(16.3) | 201(74.7) |

| I was able to reflect on my predominant learning approach after watching the video | 7(2.6) | 28(10.4) | 234(86.9) |

| I am more likely to adopt the non-surface learning approach after viewing the video | 16(5.9) | 52(19.3) | 201(74.7) |

Table 4. Participants’ response to survey on video “Be a Better Learner in Medicine”

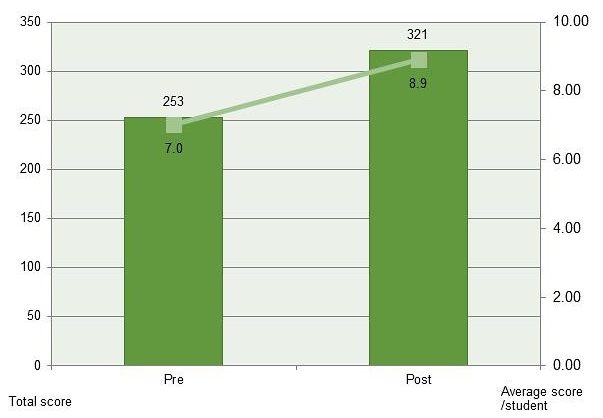

B. Participants’ Response to Survey on Video “Be a Better Learner in Medicine”

The video survey was completed by a total of 269 students. As seen in Table 4, 249 (92.0%) students thought the learning approaches explained in the video were clear, 234 (86.9%) students agreed the video helped them reflect on their predominant learning approach and 201 (74.7%) admitted that they are more likely to adopt non-surface learning approach after viewing the video. The video was found to be engaging by 193 (71.0%) students and 201 (74.7%) students thought that the duration of the video was just right.

C. Qualitative Feedback on the Video “Be a Better Learner in Medicine”

There were many qualitative comments from the students who completed the survey. There were 95 comments expressing positive views, 21 comments expressing negative views and 4 neutral comments with respect to the video depicting the learning approaches.

Some of the positive comments were “It is a more useful tool and approach to learning”, “I feel inspired by the video”, “Video illustration is helpful to elaborate different types of learner”, “The video made me reflect a little on how I learn”, “Likes the way the video brings the idea of deep learning” and “Good video to stimulate thinking on learning method”.

Addition examples of positive comments were “I feel that my own approach has been ineffective and I want my learning to improve”, “Recognise how important it is to adopt deep learning”, “It shows that my current learning method is inadequate and it shows how I should work on it”, “It is clear that deep learning allows students to learn from principle”, “I think it is important and useful to understand what we’re learning and apply it in new scenarios or situations”, “Deep is better approach with longer retention & understanding eventually beneficial to future patients.”

Some of the negative comments were “Ideally, deep approach is desirable but due to a lack of time, sometimes surface approach can be more time effective as temporary stop-gap measure”, “The amount needed to study and time needed to be a deep learner is a deterrent”, “May not have the luxury of time. (Deep learning requires a lot of time)”, “Time constraint”, “Sometimes deep learning takes time, and the short time we are given to study may push students more towards strategic thinking.”

IV. DISCUSSION

Medical students have to retain large amounts of information and at the same time have to keep themselves abreast with the latest research. The students also need to cope with heavy workloads and tight course schedules in medical school while struggling to understand and retain information with good time management skills being essential. Our study found that the majority of our students adopted the deep approach as their predominant learning approach (54.4%) followed by the strategic approach (33.6%) prior to the intervention. It is heartening to note that surface learning approach was the least preferred approach adopted by our medical students. While encouraging, there was still a substantial proportion (12%) of medical students who adopted surface learning approach as their predominant learning approach. With the rapidly advancing medical sciences, students may not have enough time to see, read and assimilate all necessary information before their assessments. This may force some of the slow learners to adopt the surface learning approach. Some students commented that surface learning approach could be adopted easily as a temporary measure due to time constraints. This might explain why 12% of medical students adopted predominantly surface learning approach in our study, and those students who were more inclined towards surface learning approach in previous studies (Aaron & Skakun, 1999; Cebeci et al., 2013; Amini et al., 2012).

After the video intervention, we noted a decrease in the surface learning approach and an increase in the strategic learning approach. As reflected in Table 3, the mean score of surface learning decreased from 62.6 to 61.4 (p=0.06.) and that of strategic and deep learning approaches increased (strategic – 72.7 to 74.6, p=0.014; deep 74.8-75.9, p = 0.120). Though this decrease in surface learning approach and increase in deep learning approaches were not statistically significant, these results reflected the potential for digital media (in the form of a video) to effect a change in the students’ learning approaches. As depicted in the qualitative comments in the video survey, some students stated that time constraint was an important factor that prevented students from adopting deep approach. The increase in strategic learning approach may be due to the need for students to pass certain assessments at the end of posting examination, as required by their schools and clerkship. A number of students had commented that adoption of strategic learning approach helped them achieve good outcomes during assessments. The students might have felt that adopting the strategic approach would be more expedient by selecting and studying the important topics amongst the intensive curricular topics and that might help them do well in a short period of attachment. The packed shortened curriculum may influence approaches to learning as evidenced from the comments in this study.

The tool used to assess students’ learning approach – ASSIST questionnaire also posed some limitations for this study. Despite the ASSIST questionnaire being validated in many cultures and, it may not fully be reflective of the true approach to learning of students, especially if they answered the questions in a way that they thought would have been the approved answers (Reid et al., 2012). In addition, ASSIST questionnaire is a self-rated tool, so the results are subjective. There may be greater awareness and a change in the students’ perception towards their learning approaches after watching the video illustrating how adopters of the various learning approaches would behave. This would have affected the results of the ASSIST questionnaire.

The video helped raise awareness of various learning approaches and engage students to reflect and reassess their predominant learning approach. The number of students adopting non-surface learning approach increased after watching the video. There is a potential to discourage them from adopting surface learning approach as reflected in the qualitative feedback which showed that many became aware of the disadvantages of surface learning. A number of students were also convinced after the video that the surface learning approach was not favourable for them to retain a lot of information that they will need to use in clinical setting. While this was a good outcome, the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, the video was just a short intervention of 12 minutes and not followed by further education or reinforcement of the appropriate learning approach throughout the posting. It is also difficult to change entrenched learning approach behaviour. In addition, most of the medical students are in their final few years of medical school, and have most likely been using their current learning approach successfully over the previous few years in medical school, and see no point in changing their learning approach. Other possible limitations include the small sample size of medical students who were involved in this study that have affected the results.

Multiple previous studies have found that many factors are involved in encouraging deep learning approach among medical students such as appropriate workload, clear goals with informative feedback and targeted assessments (Reid, Duvall, & Evans, 2005; Rushton, 2005). To facilitate deep learning, the curriculum can be adjusted to address these factors. Instead of factual overload, faculty can allocate more teaching time towards case-based scenarios and tutorials that focus on applying the understanding of pathophysiology, concepts and care management principles learned. This will aid students in tackling complex patient problems, a reality they will face when they become active practitioners. Smaller tutorial groups to focus on individualised targeted feedback after formative assessment may help in encouraging the usage of deep learning approach. The format of assessment can also be more encompassing, to reward understanding instead of pure memorising (Rushton, 2005).

The predominant deep and strategic learning approach is a reflection of self-motivation among medical students, which is inherent (Amini et al., 2012). But many students may not be aware of their own predominant learning approach and may not realize that they may adopt different approaches according to different circumstances. With the increase in the number of medical students and limited number of core faculty and time, finding a solution to encourage independent deep learning and discourage surface learning approach amongst our students would be beneficial in the long run, ensuring that students develop the most favourable learning approach from the start and keep honing this learning approach skill as they progress in their medical career.

Medical schools will also need to look into their curriculum and time-lines of individual clinical attachments periodically to ensure that they are able to deliver core knowledge without compromising on understanding of concepts. Perhaps, targeting students in their pre-clinical years and introducing the concept of various learning approaches would set a good foundation and aid in deeper learning during clinical years. Discouraging medical students from adopting surface learning approach would be beneficial in achieving expected long term goals and this would ultimate translate into higher quality education and patient care.

V. CONCLUSION

This study highlights the potential of digital media as an educational tool to enable medical students to become better learners (Gadelrab, 2011). With the use of a video, students were able to reflect on their predominant learning approaches, which is relevant with the evolving teaching andragogy that emphasises self-directed learning. The students were exposed to the potential pitfalls of adopting surface learning in the video and this likely encouraged some of the surface learners not to use surface learning approach, in order to better help them cope with the increasing need to apply strategic thinking, deep thinking and critical analysis during complex situations. This project can help spearhead efforts to optimize students’ learning, to move the medical education landscape forward.

Notes on Contributors

Sonali Chonkar, Melissa Lim and Kok Hian Tan conceived, designed the video script and the study. Melissa Lim acquired the data; Mor Jack Ng analysed and interpreted the data. Kok Hian Tan critically revised the article and gave invaluable inputs at every stage of writing and data acquisition/analysis. Tam Cam Ha and Hester Lau assisted in the revision and editing of the article.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved and given the exempt status by our institution’s Centralised Institutional Review Board of SingHealth (CIRB) committee. All students participated voluntarily and informed consent was obtained before participating in the study. The CIRB reference number for our study is 2013/232/D.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all medical students of NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, Duke-NUS Medical School and NTU Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine for participating in this joint study. We would like to thank Ms Mabel Yap from Duke-NUS Secretariat Office for her assistance in the research. We would like to thank Ms Hester Lau, Ms Tang Wan Chu, Ms Goh Jia Ying, Ms Amy Tan, Ms Alicia Lim and the staff of Division of Obstetrics & Gynaecology at KKH for the assistance in the production of the video.

Funding

This study was supported by a Teaching Enhancement Grant (TEG – AY 2014/2015) from NUS Centre for Development of Teaching and Learning.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Aaron, S., & Skakun, E. (1999). Correlation of students’ characteristics with their learning styles as they begin medical school. Academic Medicine, 74(3), 260-262.

Albedin, N. F. Z., Jaarfar, Z., Husain, S., & Abdullah, R. (2013) The Validity of ASSIST as a measurement of learning approach among MDAB students. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 90, 549-557.

Amini, M., Tajamul, S., Lotfi, F., & Karimian, Z. (2012). A survey of study habits of medical students in Shiraz Medical School. Future of Medical Education Journal, 2(3), 28-34. https://doi.org/10.22038/fmej.2012.354.

Cebeci, S., Dane, S., Kaya, M., & Yigitoglu, R. (2013). Medical students’ approaches to learning and study skills. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 93, 732-736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.271.

Chonkar, S. P., Lau, H. C. Q., Tang, W. C., Goh, J. Y., Mohammad N. B, A., Lim M., & Tan H. K. (2018, September 18). Be a predominantly deep learner in medicine [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/ttnSCoun_sA.

Ekenze, S. O., Okafor, C. I., Ekenze, O. S., Nwosu, J. N., & Ezepue, U. F. (2017). The value of internet tools in undergraduate surgical education: Perspective of medical students in a developing country. World Journal of Surgery, 41(3), 672-680. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-016-3781-x.

Entwistle, N. (1997). Contrasting perspectives on learning. In F. Marton, D. Hounsell & N. Entwistle (Eds.), The Experience of Learning: Implications for teaching and studying in higher education (3rd ed) (pp. 3-22). Retrieved from: http://www.docs.hss.ed.ac.uk/iad/Learning_teaching/Academic_teaching/Resources/Experience_of_learning/EoLChapter1.pdf.

Gadelrab, H. F. (2011). Factorial structure and predictive validity of approaches and study skills inventory for students (ASSIST) in Egypt: A confirmatory factor analysis approach. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 9(3), 1197-1218.

Leite, W. L., Svinicki, M., & Shi, Y. (2010). Attempted validation of the scores of the VARK: Learning styles inventory with multitrait–multimethod confirmatory factor analysis models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(2), 323-339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409344507.

Mitra, B., Lewin‐Jones, J., Barrett, H., & Williamson, S. (2010). The use of video to enable deep learning. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 15(4), 405-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2010.526802.

Newble, D. I., & Entwistle, N. J. (1986). Learning styles and approaches: Implications for medical education. Medical Education, 20(3), 162-175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01163.x.

Reid, W. A., Evans, P., & Duvall, E. (2012). Medical students’ approaches to learning over a full degree programme. Medical Education Online, 17(1), 17205-17211. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/meo.v17i0.17205.

Reid, W. A., Duvall, E., & Evans, P. (2005). Can we influence medical students’ approaches to learning? Medical Teacher, 27(5), 401-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500136410.

Rondon-Berrios, H., & Johnston, J. R. (2016). Applying effective teaching and learning techniques to nephrology education. Clinical Kidney Journal, 9(5), 755-762. http://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfw083.

Ruiz, J. G., Mintzer, M. J., & Leipzig, R. M. (2006). The impact of e-learning in medical education. Academic Medicine, 81(3), 207-212.

Rushton, A. (2005). Formative assessment: A key to deep learning? Medical Teacher, 27(6), 509-513. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500129159.

Samarakoon, L., Fernando, T., & Rodrigo, C. (2013). Learning styles and approaches to learning among medical undergraduates and postgraduates. BioMed Central Medical Education, 13(1), 42-47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-42.

Shah, D. K., Yadav, R. L., Sharma, D., Yadav, P. K., Sapkota, N. K., … Islam, M. N. (2016). Learning approach among health sciences students in a medical college in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. Advances in Medical Education and Practice. 7, 137-143. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S100968.

Shankar, P. R., Balasubramanium, R., & Dwivedi, N. R. (2014). Approach to learning of medical students in a Caribbean medical school. Education in Medicine Journal, 6(2), e33-40. https://doi.org/10.5959/eimj.v6i2.235.

Shankar, P. R., Dubey, A. K., Binu, V. S., Subish, P., & Deshpande, V. Y. (2005). Learning styles of preclinical students in a medical college in western Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal, 4(3), 390-395.

Shelton, P. G., Corral, I., & Kyle, B. (2017). Advancements in undergraduate medical education: Meeting the challenges of an evolving world of education, healthcare, and technology. Psychiatric Quarterly, 88(2), 225-234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-016-9471-x.

Subasinghe, S. D. L. P., & Wanniachchi, D. N. (2009). Approach to learning and the academic performance of a group of medical students – Any correlation. Student Medical Journal, 3(1), 5-10.

Tait, H., Entwistle, N. J., & McCune, V. (1998). ASSIST: A reconceptualisation of the approaches to studying inventory. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning: Improving students as learners. Oxford: Oxford Brookes University, The Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

Trigwell, K., & Prosser, M. (1991). Improving the quality of student learning: The influence of learning context and student approaches to learning on learning outcomes. Higher Education, 22(3), 251-266. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00132290.

Wickramasinghe, D. P., & Samarasekera, D. N. (2011). Factors influencing the approaches to studying of preclinical and clinical students and postgraduate trainees. BioMed Central Medical Education, 11(1), 22-28. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-22.

*Sonali Prashant Chonkar

Address: KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital,

100 Bukit Timah Road

Singapore 229899

E-mail: sonali.chonkar@kkh.com.sg

Published online: 7 May, TAPS 2019, 4(2), 39-47

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-2/OA2034

Annie L. Kilpatrick1,2, Ketsomsouk Bouphavanh3, Sourideth Sengchanh3, Vannyda Namvongsa3 & Amy Z. Gray1,2

1Centre for International Child Health, Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Australia; 2The Royal Children’s Hospital, Australia; 3Education Development Centre, Faculty of Medicine, University of Health Sciences, Lao People’s Democratic Republic

Abstract

Aim: To understand the needs and preferences of students at the University of Health Sciences (UHS) in Vientiane, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR) in relation to access to educational materials in order to develop a strategy for development of educational resources for students at UHS.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional semi-structured survey of 507 students, staff and post-graduate residents from a range of faculties at UHS regarding current learning resources, access to educational aids and online learning. Focus groups of survey participants were conducted for in-depth understanding of desired materials and challenges faced.

Results: There was an overwhelming request by students for greater access to learning resources. The main areas of difficulty include English language capacity, limited local language resources alongside poor internet access and limited competence in navigating its use. Students would prefer learning resources in their own language (Lao); many potential study hours are being consumed by students searching for and translating resources.

Conclusions: Students in Lao PDR describe multiple barriers in accessing appropriate resources for their learning. Scoping current access and needs through this research has enabled us to better plan investment of limited resources for educational material development in Lao PDR, as well as highlight issues which may be applicable to other low resource setting countries.

Keywords: Medical Education, Student Preferences, University, Learning Resources, Low Resource Setting

Practice Highlights

- At a time when information has never been more available, students in many non-English speaking countries and low resource settings face a daily challenge of information availability and inequity created by both access to technology and educational materials, which are not limited to Laos.

- For learning resources to be accessible for Lao students they need to be cost effective, language appropriate and device appropriate.

- Equipping teachers, who remain an integral tool in students learning, to face the challenges of learning resource access is vital given they face the same access barriers and must keep both their technical knowledge and teaching skills current.

- Rather than large scale development of new educational resources, there is a role of non-traditional education resource development through blogging, social media and curating of materials, alongside engaging students to empower them to access the materials they need.

I. INTRODUCTION

Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR or Laos) is a landlocked country bordering Myanmar, Cambodia, China, Thailand and Vietnam and remains classified as a least developed country (LDC) (United Nations [UN], 2015). The history of the education and healthcare development plays an important role in the current education context for Laos with many different countries contributing to development of these sectors (Dodd, Hill, Shuey, & Fernandes Antunes, 2009). Many of these stakeholders have ties with the University of Health Sciences (UHS), the sole university in the country responsible for training medical doctors through both bachelor level and post-graduate programs (Akkhavong et al., 2014).

Teachers at the UHS have largely completed medical training in-country. Limited English language capacity presents major difficulties in the ability to access up-to-date teaching resources (Milosavljevic, Vuletic, & Jovkovic, 2015; Pavel, 2014). From a geographical and linguistic perspective, the closest country involved in the Lao medical education system is Thailand, with Thai language having similarities to Lao and students and medical staff exchange occurring with Thai hospitals. Historically, the French colonial history of the country means French language is spoken among older generations and is still being taught in the medical school. More recently the importance of English as an international language has been emphasised (Pavel, 2014). The multiple languages spoken by different partner countries, combined with different approaches to medical issues creates challenges for students and staff at UHS above and beyond developing their medical competencies.

Compounding problems of language is the relative lack of learning resources in Lao language, with most text books available to students written in Thai or English. This reflects a wider paucity of written Lao language books in the general community and poorly developed reading culture which is slowly changing (Duerden, 2017). Even fewer relevant online resources exist in Lao language, meaning staff and students must navigate the vast array of online material without accompanying language capacity to distil or search information effectively. This situation impacts both the student’s capacity to learn and the staff’s capacity to teach.

Whilst there may be a range of available strategies for addressing these challenges for teaching and learning, with limited resources it is critical to understand what the best and most effective investments in educational resources might be. Yet there is little information available regarding the learning preferences and access to resources of university students in Laos, or more generally in other low resource settings. Previous studies in health science learning have mainly focused on social media use (Pimmer, Linxen, & Gröhbiel, 2012), electronic learning (e-learning; Bediang et al., 2013), computer literacy (Bediang et al., 2013; Ranasinghe, Wickramasinghe, Pieris, Karunathilake, & Constantine, 2012) and clinical skills learning (Papanna et al., 2013; Widyandana, Majoor, & Scherpbier, 2010). However, these studies do not cover a broad range of learning preferences, consider resources used for different content areas, nor consider issues of access more broadly. There were recent requests for e-learning tools in Myanmar (Bjertness et al., 2016). They highlight similar challenges in making appropriate learning and teaching material available in a country which may not have the capacity to meet the large, immediate demand for resources – but without the additional language challenges faced in Laos.

This study is the first to gather information regarding student learning preferences in Laos. We aimed to understand the current access staff and students have to educational resources, in particular online learning material and their learning preferences and needs. This information is paramount in aiding the university in their understanding of student and staff needs, in order to develop a systematic and appropriate strategy for educational resource development at UHS.

II. METHODS

A mixed-methods cross-sectional study of learning preferences and access to educational resources of staff and students at UHS was undertaken between May and November 2015. Research was guided by a phenomenological approach, which aims to examine ‘the lived experience’ of a person or several people in relation to a concept or phenomenon of interest (Liamputtong, 2009). A cross-sectional survey of staff and students was followed by focus group interviews. These two methods of data collection were designed to be complementary. The use of the surveys, representing views of a larger cross-section of the staff and student population, and focus group interviews, representing more in-depth understanding of the experience, allowed for concurrent triangulation (Castro, Kellison, Boyd, & Kopak, 2010).

The survey, consisting of fifteen questions, was developed by the researchers. The questions were designed with the intent to capture a range of information addressing the aims of the study. Questions related to current learning resources, access to educational aids and online learning and perceived educational resource needs. The survey was initially written in English, and then translated into Lao language for completion by participants. Participants included 183 fourth and sixth-year medical students, 105 nursing, 72 dentistry, 64 pharmacy, 5 physiotherapy and 4 medical technology students, along with 53 medical residents and 19 faculty staff. Fifth-year medical students were not available due to external clinical rotation. Staff were included since any strategies to address educational resource availability would need to take into account the access and capacity of staff responsible for teaching.

Surveys were distributed to students in lectures and to faculty staff and medical residents in education meetings in the university and hospital respectively. Researchers explained the study, its anonymity and the voluntary nature of its completion to participants, in Lao language, and consent was implied by completion and return of the survey. Survey results were entered into an EpiData database then analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Version 24). Categorical data were described according to the number and percentage of participants in each group. Comparison between groups was performed using chi-square.

Stratified sampling was used for the focus groups, with students volunteering from specific sub-groups after they had completed the survey. One focus group was conducted with each of the main student cohorts – medical, pharmacy, nursing and post-graduate medical. Students were provided with a written plain language statement, a verbal explanation, and opportunity to withdraw, then signed a written consent form.

Focus groups were conducted using an interview guide structured around three main questions – current learning materials and how these are accessed; main barriers to accessing learning material and; the learning material needs. Interviews were conducted in English with translation into Lao. Data were audio recorded and transcribed into written documents. The written Lao content was translated to the English language before analysis. Inductive qualitative content analysis was performed by the primary researcher (AK) to elaborate on the survey findings.

III. RESULTS

507 (61.3% female, 36.7% male) students and staff completed the survey from a total of 800 potential participants (response rate 63.4%). Almost half of the participants were older than 25 years of age (Table 1) and the vast majority (81.5%, 413/507) had been in the workforce before medical school. The majority (52.7%, 267/507) of participants were from provinces outside of the capital (Table 1). The largest student cohort was medical students (36.1%) followed by nursing students (20.7%) (Table 1). Faculty staff made up less than 4% of participants (Table 1) and there were no significant differences in their responses compared to students.

The majority (98.0%) of participants own smart phones, for example 18/19 faculty staff, 178/183 medical students and 97/105 nursing students. Smart phones are participant’s main access to the internet, with less access to computers or tablets (Table 2). Over 90% of survey participants (478/507) reported barriers to internet access, with 56.8% (288/507) not having access to internet in their home and very few having access in their educational institutions (Table 2). One hundred percent of faculty staff reported barriers to internet access compared to 95% of nursing and 93% of medical students. There are many barriers to internet access including cost (62.9%), speed (65.1%), language (41.0%) and a lack of understanding (8.1%), and these were also verified in focus group discussions. Sixteen of the 19 staff members said cost was a barrier compared to 114 of the 183 medical students and 67 of the 105 nursing students. Of the 19 staff members, 3 reported language as a barrier, compared with 69/183 medical students and 34/105 nursing students.

| Variable | n (%) |

| Age | |

| <25 years | 278 (54.8) |

| 25-29 years | 105 (20.7) |

| 30-35 years | 52 (10.3) |

| >35 years | 49 (9.7) |

| Not specified | 23 (4.5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 311 (61.3) |

| Male | 186 (36.7) |

| Not specified | 10 (2.0) |

| Origin | |

| City | 164 (32.3) |

| Province | 267 (52.7) |

| Not specified | 76 (15.0) |

| Position | |

| Medical Students Yr 4+6 | 183 (36.1) |

| Nursing Students | 105 (20.7) |

| Dentistry Students | 72 (14.2) |

| Pharmacy Student | 64 (12.6) |

| Medical Residents Yr 1-3 | 53 (10.5) |

| Faculty Staff | 19 (3.7) |

| Physiotherapy | 5 (1.0) |

| Medical Technology Student | 4 (0.8) |

| Not specified |

2 (0.4) |

Table 1. Demographics of 507 study participants

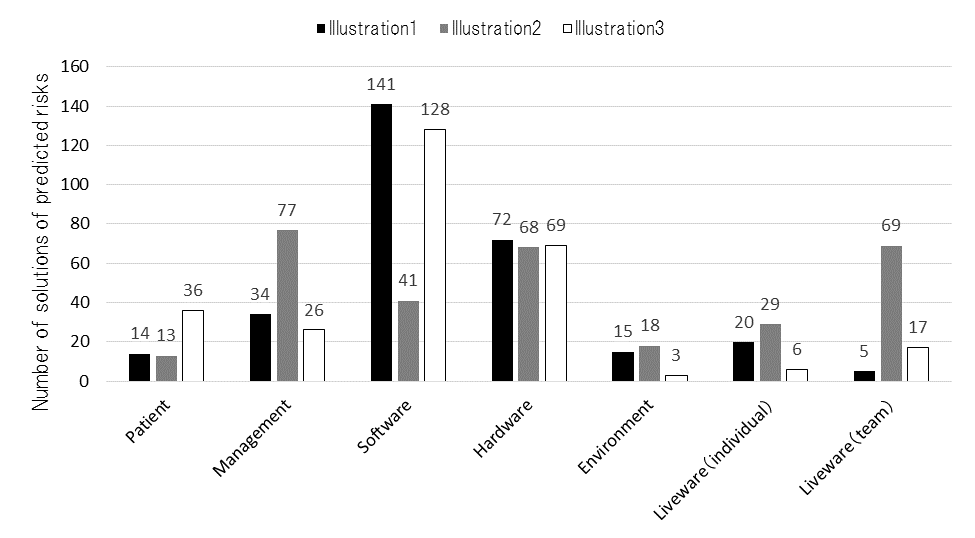

A. Educational Resources

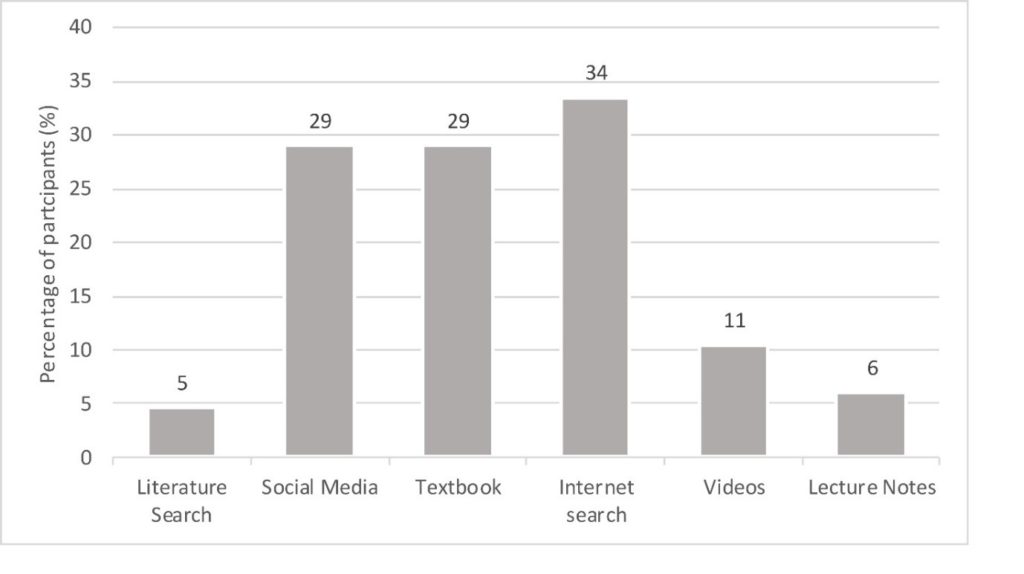

More than half of participants (294/507) access the internet daily for study purposes whereas 20.9% (106/507) access the internet monthly or less. Medical students and residents have a higher percentage of daily internet use (71%) compared with non-medical students (48%, p < 0.001) although there was no difference in smartphone ownership or internet at home. Around one third of participants used internet search tools, social media and text books for education daily (Figure 1). The social media applications used included Facebook (85.8%), WhatsApp (69.6%) and Line (42.6%).

| Total

n (%) |

Medical student

n (%) |

Nursing students

n (%) |

Staff

n (%) |

|

| Technology Ownership | ||||

| Smart Phone | 497 (98.0) | 178 (97.3) | 97 (92.4) | 18 (94.7) |

| iPad | 61 (12.0) | 28 (15.3) | 5 (4.8) | 2 (10.5) |

| Tablet | 35 (6.9) | 16 (8.7) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (5.3) |

| Laptop | 101 (19.9) | 29 (15.8) | 14 (13.3) | 10 (52.6) |

| Personal Computer | 284 (56.0) | 104 (56.8) | 43 (41.0) | 13 (68.4) |

| Location of internet access | ||||

| Phone | 487 (96.1) | 175 (95.6) | 96 (91.4) | 18 (94.7) |

| Internet Café | 96 (18.9) | 38 (20.8) | 13 (12.4) | 4 (21.1) |

| University | 51 (10.1) | 15 (8.2) | 10 (9.5) | 8 (42.1) |

| Hospital | 56 (11.0) | 22 (12.0) | 8 (7.6) | 0 (0) |

| Barriers to internet access

Cost |

319 (62.9) |

114 (62.3) |

67 (63.8) |

16 (84.2) |

| Language | 208 (41.0) | 69 (37.7) | 34 (32.4) | 3 (15.8) |

| No Computer | 45 (9.1) | 8 (4.4) | 16 (15.2) | 3 (15.8) |

| Lack of Understanding | 41 (8.1) | 8 (4.4) | 12 (11.4) | 0 (0) |

| Internet Speed | 330 (65.1) | 113 (61.7) | 44 (41.9) | 14 (73.7) |

Table 2. Technology ownership, internet access and barriers among the study cohort of staff and students at The University of Health Sciences Lao PDR

Figure 1. Percentage of students and staff at The University of Health Sciences Lao PDR using specific educational resources on a daily basis

Focus group participants most commonly described accessing learning materials via personal smart phones for internet searches. Internet site searches involved mainly the use of the google search engine and sites such as You-Tube or Wikipedia rather than formal searching for journal articles or other medical resources. Subscriptions for journal article access or peer reviewed medical information sites were scarce with cost again listed as a barrier and also a source of inequity.

“On YouTube we looking for procedures or listening to heart-sound. Sometimes looking for lecture.”

(Medical student)

Social media sites are used to share difficult or interesting cases, pictures or videos. Lecture notes were used frequently, either as handouts of digital presentations or photocopied projector slides, but were generally not available online.

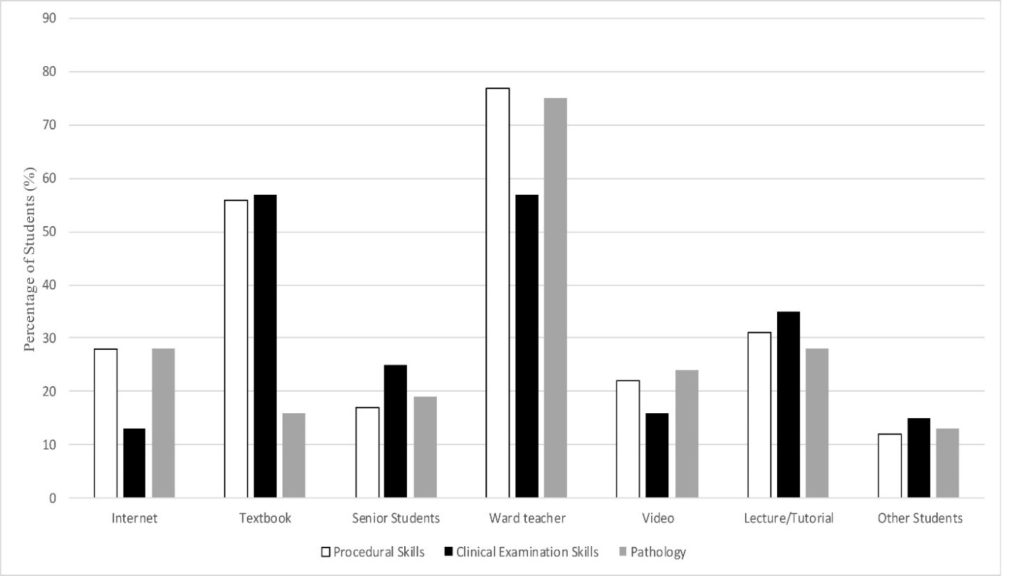

With regard to learning specific skills including procedures, clinical examination and pathology traditional educational resources such as ward teachers and textbooks still dominate other modalities, including online learning (Figure 2). This is despite concerns raised by students in focus groups about the currency of knowledge available through these avenues.

Figure 2. Use of educational resources for learning in specific content areas by students at The University of Health Sciences, Lao PDR

Focus groups described access to only a small number of appropriate books in the university library which were perceived to be “too old”, “not in Lao” and insufficient in number.

“…there is only one copy of the text we need.”

(Nursing student)

Personal ownership of books is limited to those who can afford it. These books are commonly shared between friends and are stated to be predominantly written in Thai language.

Focus groups described their ideal properties of learning materials as easy to access, in the Lao language and up-to-date. Access included availability to all students prior to the relevant lesson, availability on their smart phone despite often limited internet bandwidth, and being available offline when the internet was not available. Lao language books, guidelines and other resources are needed.

B. Language

More than 80% (413/507) of participants stated that all, or the majority, of their learning resources were in Lao language. The staff cohort had an overall lower percentage to this, with 53% (10/19) stating that all or the majority of their resources were in Lao. Very few to no Lao language resources were used by 7.7% (39/507) of participants. Lao was the most popular preference of learning resource language (38%), yet strong preferences were also described for having the same resource in various combinations of Lao, Thai and English.

Focus groups described the difficulty of finding any Lao language learning materials. Students reported using mostly Thai language resources or English which was then translated through sometimes multiple steps.

“It is so hard to find Lao language. We put English into Google translate to make into Thai and then make this to Lao in our head.”

(Medical resident)

IV. DISCUSSION

Access to appropriate and adequate learning resources is a daily challenge for students and staff at UHS in Lao PDR with an overwhelming need for greater access to learning resources, which are up-to-date, in their local language and available both on and offline. The study highlights the rise of social media as a learning tool even in an environment where there are multiple barriers to internet access. At the same time there is still high use of traditional learning resources, including ward teachers and text books, for specific skills such as physical examination and procedures – even when other media, such as videos, may have potential advantages. Finally, the research illustrates the disadvantage caused by language capacity, in particular the inequity in access to resources due to second language skills with the same problems of access impacting on what staff teach.

Our study population is comparable to both the general Lao population and the UHS student population, with a response rate of over 60%. Most of the survey participants were from provinces outside of the capital city of Vientiane, which is consistent with the general Lao population (UN, 2015). Given the Lao population is relatively young compared to other countries (UN, 2015), it is notable that almost half of the participants were older than 25 years of age and many had worked between completing secondary school and commencing their university degree, demonstrating the financial strains that students must also contend with in order to complete their degrees.

Consistent with previous literature from low-income countries internet speed (Bjertness et al., 2016) and cost (Aboshady et al., 2015; Bjertness et al., 2016) are major challenges. The average internet download speed in Lao PDR is more than five times slower than the speed achieved in Australia (Thompson, Sun, Möller, Sintorn, & Huston, 2016). This is the average, with most students only being able to afford 2g or 3g internet for smartphones and therefore having much slower download speed making smartphone internet access impractical for learning. The cost of the internet for students was reported to be on average one US dollar per day which is a large relative expense compared to the Gross National Income (GNI) in Lao PDR of $1740 USD/year (The World Bank Group, 2017a). With advances in technology and internet access globally it may be anticipated that there will be improvement in internet access, speed and affordability. Sustainable Development Goal 9.c states an aim to provide universal and affordable access to Internet in the least developed countries by 2020 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014). However, countries such as Lao PDR who would benefit significantly from these changes, also often lag behind other countries in how quickly they can access them, or how quickly these solutions become affordable to those who need them.

Not dissimilar to well-resourced countries (Arnbjornsson, 2014; Avcı, Çelikden, Eren, & Aydenizöz, 2015; Cartledge, Miller, & Phillips, 2013; Hollinderbäumer, Hartz, & Uckert, 2013) a large percentage of Lao students use social media applications for study. In a study by Guarino et al. (2014), in a high resource setting, the main reason for use of social media was logistical purposes. Our study population commonly use social media for sharing case-based information raising a clear concern regarding confidentiality in what is an unmonitored social media environment. In addition to this there is difficulty moderating the content or quality of shared information. In a country where access to evidence-based information is challenging, there is a risk that false information and misconceptions are shared without correction. There is literature supporting the safe use of social networking in medical education (Cartledge et al., 2013; Cheston, Flickinger, & Chisolm, 2013). Whilst there is no existing policy within the Lao University on social media this study highlights the potential need for policy development. A university website or specific faculty or clinical websites could be better forums for sharing case-based information, but due to resource constraints these are presently not viable options. A final alternative is for learning resources to be made available through the social media platforms which are used and through which information is already shared.

Consistent with a previous study (Guarino et al., 2014) participants have stated a higher use of Google and Wikipedia over journal articles or other evidence based medical sites. The reason hypothesised in the study by Guarino et al. (2014) was possible diffidence of students, rather than access, which was commonly cited in our study. Along with ease of free access to Wikipedia, although not explicitly stated, Lao students may find the language accessibility of Thai and some Lao articles another motivating factor to use this site.

The preferred language for any learning resource in this context is understandably Lao. English is now recognised by the UHS as the most important second language for their graduates, and participants in our study recognise the need to access English language learning resources. However, the language competence of most students and staff means Lao resources remain vital, yet few exist. Our study highlights the time students are spending searching for and translating resources from other languages. In a country in which human resource capacity is still being built and the standard of high school and university education remains behind its regional neighbours (The World Bank Group, 2017b) – this is time that cannot afford to be lost. This is a potential source of inequity in medical education globally – whereby countries with the lowest English language literacy often have the greatest need for better educational resources, the least capacity to generate resources in their own language, and the largest gaps in education delivery. Addressing this deficit requires a strategic approach which optimises the impact and reach of any intervention, as well as the use of limited financial and human resources available to develop and translate materials and takes into account technological limitations.

There are multiple different strategies which could be considered to solve the problem of access to learning and teaching resources. One approach option is to translate desired textbooks into Lao language and have these readily available to students and staff. However, this consumes substantial amount of resources and time and by completion the texts themselves may outdate quickly. Support for faculty to review the quality and currency of lecture material, which could then be made available online, would build capacity of teachers and allow what is taught to be visible. Work is already being done to improve free access to online journal databases and evidence-based medical websites but these efforts are still hampered by difficulties with language or internet access. Alternatively, non-traditional methods such as blogging to create key Lao language resources, lecture materials and provide clear summaries may provide a solution that is more efficient and more easily adaptable over time. Furthermore, inviting the students to collaborate on these materials may empower them to learn, as they are currently disempowered through language barriers and lack of access to educational materials. This would facilitate students with higher English language and computer skills to support their peers. The significant difference in daily internet use between the medical cohort and other groups would need to be taken into account for any resources. The greater daily internet use by medical students compared to other student cohorts did not reflect greater access to Information Technology (IT) or the internet. It may reflect greater IT skills among the medical cohort, or alternatively better understanding of the internet resources they can access, or usefulness of those materials.

Finally, the importance of teachers as facilitators of learning cannot be ignored. Students stated for all practical learning situations that ward teachers are the most used resource over text books and internet. Any e-learning resource created in response to this study must be seen as an adjunct to support teachers; to standardise and optimise the quality of teaching and learning content, facilitate information sharing but not replace teachers. Equipping teachers, who are vital learning resources for students, to face this challenge is paramount as they face the same challenges that students do in accessing information, acquiring second language skills and keeping both their technical knowledge and teaching skills current.

Potential limitations of the study include students feeling obliged to participate or unable to speak openly in focus groups due to involvement of UHS staff in the research team. We attempted to minimise this impact by using both quantitative and qualitative data methods to explore the same issues, ensuring students were given multiple opportunities to opt out of focus groups and keeping the focus group environment informal. Strengths of this study include the high response rate of participants with a combination of quantitative and qualitative data collected. Focus groups were important for students as they created discussions that enabled students to discuss and compare challenges. They were also a learning opportunity as students heard from each other how they studied and the different resources available.

Despite these limitations our study clearly demonstrates an acute issue of access to local language resources for teaching and learning among staff and students at the sole institution responsible for training doctors in Lao PDR. Whilst Laos may be somewhat unique in its lack of available local language resources, both for the general as well as the medical population -the problem of availability of medical texts or resources in a local tongue exists among other non-English speaking countries (Sabbour, Dewedar, & Kandil, 2010). Many of these countries may also be low resource countries who are reliant on donor funds, and donor priorities to determine what is funded. Solutions such as investment in English language capability of students take time to generate change, rely on changes to the basic education system, detract from time spent on medical content, disadvantage students from lower socio-economic backgrounds and may not lead to better outcomes overall (Dearden, 2014). Furthermore, they create an imbalance when the English language capacity of the teachers may not receive the same investment. Solutions such as the increasing capacity of artificial intelligence to accurately translate online materials may be a more disruptive solution; but will also potentially require new approaches to appropriately integrating materials from diverse sources into curricula.

V. CONCLUSION

Our research highlights the daily challenges and the inequity faced by many non-English speaking countries in this time of exponential availability of information online. English language capacity, minimal local language resources and difficult access to information technology underpinned by the historical context of the Lao education system create enormous barriers for teaching and learning. For learning resources to be accessed sufficiently they need to be cost effective, language appropriate and device accessible. This will not only improve the learning for university students in Lao PDR, but the capacity of their teachers and also their future working selves in continuing professional development.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Annie L. Kilpatrick is a general paediatric trainee who worked as a paediatric clinical education fellow in Lao PDR in 2015 to 2016. She designed and conducted the surveys and focus groups, retrieved data, performed calculations, interpreted results, conceived and wrote the manuscript.

Dr Ketsomsouk Bouphavanh is the Director of The Education Development Centre and the Vice Dean of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Health Sciences in Vientiane, Lao PDR. He was involved in conceiving and coordinating the research project and contributed to the manuscript.

Dr Sourideth Sengchanh is a paediatrician who works in The Education Development Centre at the University of Health Sciences in Vientiane, Lao PDR. He was involved in coordinating the project, facilitating and translating survey completion and focus groups and contributed to the manuscript.

Dr Vannyda Namvongsa is a paediatrician in Vientiane, Lao PDR who is heavily involved in teaching medical students and paediatric trainees. She was involved in coordinating the research project, facilitating and translating survey completion and focus groups and contributed to the manuscript.

Dr Amy Z. Gray is a consultant paediatrician and senior lecturer. She designed and conducted surveys and focus groups, contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval for the project was obtained from the Lao National Health Ethics Committee (2015.76.NIOPH.72.VIE) and The University of Melbourne Ethics Committee (1544310).

Acknowledgements

This work was completed in full collaboration with the staff of The Education Development Centre, University of Health Sciences Lao PDR who facilitated the data collection. The authors especially acknowledge the time that the Lao students and staff spent completing the surveys and participating in the focus groups.

Funding

No funding source was required for this paper or research study.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

Aboshady, O. A., Radwan, A. E., Eltaweel, A. R., Azzam, A., Aboelnaga, A. A., Hashem, H. A., … Hassouna, A. (2015). Perception and use of massive open online courses among medical students in a developing country: Multicentre cross-sectional study. BioMed Central Open, 5(1), e006804.

https:doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006804

Akkhavong, K., Paphassarang, C., Phoxay, C., Vonglokham, M., Phommavong, C., Pholsena, S. (2014). The Lao People’s Democratic Republic health system review (Series Ed.). Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 4(1). Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Retrieved from

https://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/10448

Arnbjornsson E. (2014). The use of social media in medical education: A literature review. Creative Education, 5(24), 5.

Avcı, K., Çelikden, S. G., Eren, S., & Aydenizöz, D. (2015). Assessment of medical students’ attitudes on social media use in medicine: A cross-sectional study. BioMed Central Medical Education, 15(1), 18.

Bediang, G., Stoll, B., Geissbuhler, A., Klohn, A. M., Stuckelberger, A., Nko’o, S., Chastonay P. (2013). Computer literacy and e-learning perception in Cameroon: The case of Yaounde faculty of medicine and biomedical sciences. BioMed Central Medical Education, 13(1), 57.

Bjertness, E., Htay, T.T., Maung, N.S., Soe, Z.W., Aye, S.S., Ottersen, O.P., … Amiry-Moghaddam, M. (2016). E-learning resources in Myanmar. The Lancet, 388(10063), 2990-2991.

Cartledge, P., Miller, M., & Phillips, B. (2013). The use of social-networking sites in medical education. Medical Teacher, 35(10), 847-857.

Castro, F., Kellison, J., Boyd, S., & Kopak, A. (2010). A methodology for conducting integrative mixed methods research and data analyses. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 4(4), 342–360.

Cheston, C. C., Flickinger, T. E., & Chisolm, M. S. (2013). Social media use in medical education: A systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(6),893-901.

Dearden, J. (2014). The Conversation: Lessons taught in English are reshaping the global classroom. Retrieved May 2018, from https://theconversation.com/lessons-taught-in-english-are-reshaping-the-global-classroom-25944

Dodd, R., Hill, P.S, Shuey, D., & Fernandes Antunes, A. (2009). Paris on the Mekong: Using the aid effectiveness agenda to support human resources for health in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Human Resources for Health, 7(1), 16.

Duerden, J. (2017, January 25). Nascent book culture spreads in rural Laos. Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved from

https://asia.nikkei.com/Location/Southeast-Asia/Myanmar-Cambodia-Laos/Nascent-book-culture-spreads-in-rural-Laos

Guarino, S., Leopardi E., Sorrenti, S., De Antoni, E., Catania, A., Alagaratnam, S. (2014). Internet-based versus traditional teaching and learning methods. The Clinical Teacher, 11(96), 449-453.

Hollinderbäumer, A., Hartz, T., & Uckert, F. (2013). Education 2.0—How has social media and web 2.0 been integrated into medical education? A systematical literature review. German Medical Science Journal for Medical Education, 30, 7-12. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000857

Liamputtong, P. (2009). Qualitative Research Methods. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Milosavljević, N., Vuletić, A., Jovković, L. (2015). Learning medical English: A prerequisite for successful academic and professional education. Srpski Arhiv za Celokupno Lekarstvo [Serbian Archives of Medicine], 143(3-4), 237-240.

Papanna, K. M., Kulkarni, V., Tanvi, D., Lakshmi, V., Kriti, L., Unnikrishnan, B., … Sumit Kumar, S. (2013). Perceptions and preferences of medical students regarding teaching methods in a Medical College, Mangalore India. African Health Sciences, 13(3), 808-813.

Pavel, E. (2014). Teaching English for medical purposes. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov. Series VII: Social Sciences • Law, 7(56)(2), 39-46. Retrived from

http://webbut.unitbv.ro/BU2014/Series%20VII/BULETIN%20VII/06%20Pavel%202-2014.pdf

Pimmer, C., Linxen, S., Gröhbiel, U. (2012). Facebook as a learning tool? A case study on the appropriation of social network sites from mobile phones in developing countries. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 726-738.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01351.x

Ranasinghe, P., Wickramasinghe, S.A., Pieris WR, Karunathilake I., Constantine, G.R. (2012). Computer literacy among first year medical students in a developing country: A cross sectional study. BioMed Central Research Notes, 5(1), 504.

Sabbour, S. M., Dewedar, S. A., & Kandil, S. K. (2010). Language barriers in medical education and attitudes towards Arabization of medicine: Student and staff perspectives. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 16(12), 1263–1334.

Thompson, J., Sun, J., Möller, R., Sintorn, M., & Huston, G. (2016). Akamai’s [state of the internet], Q1 2016 report. Cambridge, MA: Akamai Technologies, Inc. Retrieved from

https://www.akamai.com/kr/ko/multimedia/documents/state-of-the-internet/akamai-state-of-the-internet-report-q1-2016.pdf

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2014). Open Working Group proposal for Sustainable Development Goals. Retrieved May 2018, from

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgsproposal.html.

United Nations. (2015). Country Analysis Report: Lao PDR: Analysis to inform the Lao People’s Democratic Republic – United Nations Partnership Framework 2017-2021. Retrieved May 2018, from http://www.la.one.un.org/images/Country_Analysis_Report_Lao_PDR.pdf

Widyandana, D., Majoor, G., & Scherpbier, A. (2010). Transfer of medical students’ clinical skills learned in a clinical laboratory to the care of real patients in the clinical setting: The challenges and suggestions of students in a developing country. Education for Health (Abingdon, England), 23(3), 339.

The World Bank Group. (2017a). Data for Lao PDR, Lower middle income [Data]. Retrieved from

http://data.worldbank.org/?locations=LA-XN.

The World Bank Group. (2017b). Education [Data]. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/topic/education?locations=LA-TH-VN-KH-MM

*Amy Z. Gray

50 Flemington Road,

Parkville Victoria 3052, Australia

Phone: +61 3 9345 4647

Facsimile: (03) 93456667

Email: amy.gray@rch.org.au

Published online: 7 May, TAPS 2019, 4(2), 32-38

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2019-4-2/OA2054

Stefan Kutzsche1 & Erwin Jiayuan Khoo2

1Centre for Education, International Medical University, Malaysia; 2Clinical School, International Medical University, Malaysia

Abstract

We are reporting the results of implementing Learning from Observation and Discussions at Clinical Campus International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). This initiative was conceived and successfully implemented with the aim to identify medical students’ learning perception from self-reported learning experiences. A total of 80 semester eight medical students were invited to participate in the study. A structured, validated and reliable instrument developed from a work skill development framework was used to assess students’ perception of learning through discussions and observations (Total D&O), input from their experience providing future ideas (Total Ideas) and guided ward rounds as a new learning format (Total Visit). Informed consent was obtained from 42 students who participated over the ten-month period of the study. Data was analysed with ANOVA and structural regression equation modelling. The study showed that both Total Visit and Total Discussion & Observation can predict Total Perception of Learning. According to student evaluations, the Total Visits rating was the best single predictor summarising positive perception of rounds at the neonatal intensive care unit based on the significance values, partial eta squared and power. Students ranked the process of guided rounds at the neonatal intensive care unit as valuable in providing educational experiences and integral to their learning perception.

Keywords: Perception of Learning, Bedside Teaching, Clinical Neonatology, Observational Learning

Practice Highlights

- The study seeks to test whether observational learning by medical students can predict a student’s perception of learning at NICUs.

- Students benefit and learn from active and purposeful NICU rounds supervised by a neonatologist.

- Total Visits rating was the best single predictor of a positive perception of NICU rounds based on the significance values, partial Eta squared and power.

- The study supports the adoption of observation-based learning exercises to augment the traditional case presentations in medical student training

I. INTRODUCTION

Despite a decline in practice, bedside teaching (BST) remains an important component of education for students of medicine and other health professions in helping to develop knowledge, skills and attitudes (Peters & Ten Cate, 2014; Stickrath et al., 2013). BST can be adapted to various clinical departments including the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Approved learning outcomes for fourth-year medical students rotating at the Special Care Nursery (SCN) involve demonstration of medical knowledge, comprehension of pathophysiology and formulating management plans.

Although it is widely accepted that medical students benefit and learn from active and purposeful NICU rounds, there is little prospect of learning proficiently without guidance and a purposeful curriculum (Biggs & Tang, 2011). Some teaching hospitals even restrict access to NICUs for medical students due to the risk of infections or possible conflicts of interest with other health professionals and parents. Hence, students are more likely to refer to ward rounds at the SCN where clinically stable infants may need feeding training, rooming-in, phototherapy or antibiotics, and are usually expected to be discharged within a few days or weeks. In contrast, NICUs are designed for newborns in need of specialised, high-tech medical and nursing care, including respiratory support. The unit provides care for the most complex conditions in the neonatal period, and may also include surgical care and transport of critically ill newborn infants. The NICU experience of medical students includes observational learning, sharing of knowledge, good practice, and identifying ethical issues. However, patients in the SCN and NICU are difficult to enlist for autonomous and self-directed learning. It is evident that clinical teaching in the NICU where hands-on practice is limited, and multiple learning models co-exist, includes understanding, application, critical, thinking, creativity and communication in addition to formal learning (Bannister, Hilliard, Regehr & Lingard, 2003). The clinical teacher, therefore, performs a key and highly demanding role in ensuring that learning outcomes are met.