The development of clinical confidence during the PGY-1 year in a sample of PGY-1 doctors at a District Health Board (DHB) in New Zealand

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2018, 3(2), 29-37

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-2/OA1051

Wayne A. de Beer & Helen E. Clark

Waikato District Health Board, Hamilton, New Zealand

Abstract

The New Zealand Curriculum Framework (NZCF) for Prevocational Medical Training identifies a number of procedural skills that prevocational doctors should achieve during their first two years following graduation from medical school. This study aimed to identify the clinical confidence of graduate doctors in performing the list of procedures outlined in the NZCF at two points in time; following completion of undergraduate studies, and the first year of prevocational, preregistration training. An anonymous paper-based survey, consisting of 59 items, was completed by a cohort of PGY-1 doctors (n = 30) twice during 2015, with the first 48 items of the survey rating PGY-1s perceptions of their clinical confidence in performing procedures that fall under the 12 competencies identified in the Procedures and Interventions section of the NZCF. 70.8% of the procedures were rated above 2.0 at the start of the PGY-1 year, indicating that respondents had received teaching in, or viewed the procedure being performed, during undergraduate training. By year-end, procedural skills performance rated above 3.0 (i.e., confident in performing said procedure independently) was achieved in 52% of the listed skills. Low scores occurred in procedures listed under the categories ENT, Ophthalmology, Surgery and Trauma. While ratings of clinical confidence improved in many areas as expected during the PGY-1 tenure, some areas remained low. This highlights an issue that PGY-1 doctors may not be receiving adequate training in certain procedural skills listed as core NZCF competencies during the PGY-1 year.

Keywords: Prevocational Doctors, Core Competencies, Procedural Skills, Clinical Confidence

I. INTRODUCTION

The New Zealand Medical Council (NZMC) published its New Zealand Curriculum Framework (NZCF) for prevocational medical training in February 2014, with the curriculum implemented in November 2014 (Medical Council of New Zealand [MCNZ] , 2014). The curriculum framework identified the expected learning outcomes for doctors during the first two years of employment following graduation from one of the two New Zealand medical schools. These two years are referred to as the Post-Graduate Year-1 and -2 (PGY-1 / -2) years.

The NZCF is designed to reflect the continuum of learning that starts during undergraduate training and continues during the PGY-1 and -2 years (MCNZ, 2014). The aim of the learning outcomes and, in particular, procedural competence is to promote and ensure patient safety (Patel, Oosthuizen, Child, & Windsor, 2008). To obtain general registration at the end of the PGY-1 year, doctors should have achieved sufficient experience in competently performing a substantive number of the procedures. The PGY-2 year allows for further refinement of procedural skill learning and helps to prepare house officers for vocational training.

The NZCF consists of five sections: Professionalism, Communication, Clinical management, Clinical problems and Conditions, and, Procedures and Interventions. Six overarching outcome statements apply to the execution of the Procedures and Investigations section. These relate the doctor’s ability to provide “safe treatment to patients by competently performing certain procedural and assessment skills” e.g. take informed consent, preparation and post procedure care (MCNZ, 2014). Procedural skills are listed under 12 categories (Table 2). During the PGY-1 year, doctors should achieve competency in 48 identified procedures (NZCF lists 47 procedures, however for measurement purposes we separated female and male bladder catheterisation procedures).

In addition to apprenticeship training achieved during the clinical attachments, various other learning opportunities exist for procedural skills learning during prevocational training. At the organisation where this study took place, six 1.5 hours’ sessions were scheduled for procedural skill learning at a skills simulation centre. PGY-1 doctors were also required to attend an 8-hour advanced life support training session to achieve the New Zealand (NZ) Certificate of Resuscitation (CORE). Formal education sessions provided additional opportunity to teach the theory to support procedural learning.

In this study, the PGY-1 doctors were asked to rate their confidence levels in the performance of several listed procedures. Clinical confidence was defined as an “acquired attribute that provides individuals with the ability to maintain a positive and realistic perception of self and abilities.” (Evans, Bell, Sweeney, Morgan, & Kelly, 2010). It is important to note that ‘clinical confidence’ and ‘clinical competence’ are not necessarily equivalent, with a brief definition of the latter being “the capability to perform acceptably those duties directly related to patient care”. Clinical competence can only be measured by standardised assessment frameworks such as those based on Miller’s pyramid model (Miller, 1990). On the other hand, clinical confidence is a self-assessment, which is not necessarily measurable by standardised tests. Students’ abilities to correctly self-assess have been documented frequently in the medical literature and procedural confidence was identified as an important concept (Fitzgerald, White, & Gruppen, 2003). Two previous studies pointed to procedural confidence as affecting the students’ willingness to engage in the procedure, engage in accurate self-assessment, and to seek external help in performing the procedure (Byrne, Blagrove, & McDougall, 2005; Hays et al., 2002).

The respondents’ ratings of clinical confidence in each of the identified procedures were compared at the start and end of the PGY-1 year. The first rating, at the start of the year aimed to identify their clinical confidence in undertaking procedures following their undergraduate training. This would theoretically reflect the degree to which the two NZ-based undergraduate programmes helped prepare students to learn procedural skills in clinical settings. By assessing their confidence at the end of the PGY-1 year, the authors wanted to assess the direction and degree of any changes in confidence in procedural skills performance because of PGY-1 training.

Benner’s Stages of Clinical Competence was used and adapted to medical training to define different levels of perceived confidence (Benner, 1984). Five statements guided house officers to determine their level of clinical competence in the procedural skills outlined (Table 1).

|

Scale: |

Score |

| I know very little about this activity / task and have never had any practice in the skills lab or in real life | 0 |

| I know about this skill because I have received (objective) teaching (e.g. a lecture, read about it in a text book) and /or seen it performed by others. | 1 |

| In addition to the statement immediately above, I have received skills training by a teacher or supervisor and have performed this skill on 1-3 occasions. I still feel very uncertain about it and can’t perform this without someone senior supervising me directly or checking on the outcome afterwards. Therefore, I don’t feel confident that I have mastered this activity / task yet. | 2 |

| I have had several practices in the activity; I feel able to perform it independently in most settings. Even when I experience some difficulties / challenges with the task / activity I can manage. | 3 |

| I do this activity so often that I can perform it without actively thinking (about the steps) and at times subconsciously. I am confident that I perform this task adequately; I am safe and don’t generally need supervision in this task at all. | 4 |

Table 1. Survey statements based on Benner’s stages of clinical competence

II. METHODS

The Clinical Education & Training Unit (CETU) at Waikato District Health Board (DHB) designed a paper-based survey, consisting of 59 items based on the competencies stated within the NZCF. These items were scored from 0-4; the score reflecting house officers’ perception of their clinical confidence level (Table 1). The first 48 items rated their confidence in performing procedures within the 12 categories identified in Table 2.

|

Cardiopulmonary (5 items) Diagnostic (7 items) Ear Nose Throat (2 items) Injections (2 items) Intravenous/intravascular (7 items) Mental Health (1 item) Ophthalmic (5 items) Respiratory (5 items) Surgical (6 items) Trauma (4 items) Urogenital (2 items) Women’s Health (2 items) |

Table 2. Clinical skills and procedures item categories

Items 49 – 59 were designed to measure additional skills that fell within categories of leadership, administrative and communicative skills. The results for these items will be discussed in a separate publication.

A review of the Standard Operating Procedures of the Health and Disability Ethics Committee (HDEC) determined that the study did not require formal ethics approval, due to meeting guidelines around health information, human tissue and human participants, as outlined in the HDEC scope summary (Health and Disability Ethics Committee, 2016). Ethical standards were adhered to.

All PGY-1s (n = 30) who commenced working at Waikato DHB in 2015 were asked to complete the survey twice in 2015. Participants were offered the choice of partaking and could withdraw involvement at any stage. The first survey (baseline) was conducted at the start of the 2015 PGY-1 orientation period, while the second survey was conducted at the end of the 4th quarter. Response rate was high; 100% (30 respondents) at baseline, and 83% (25 respondents) at the end of the year (EOY). Survey identification numbers were used to track individual progress while maintaining respondent confidentiality. Demographic data related to gender and medical school attended prior to PGY-1 level was also collected.

III. RESULTS

All survey responses were recorded and analysed. Cronbach’s Alpha was .964 for the baseline survey and .868 for the EOY survey, which showed that the items had high internal consistency at both time points. Differences between individual item means at baseline and EOY were statistically analysed by using the Wilcoxon signed-ranked test.

Table 3 outlines the demographic data of our respondents (where identified). Sixty percent of our PGY-1 doctors were female. Of the group, 63.3% studied at the University of Auckland with 30% coming from the University of Otago.

| Demographics | Baseline

(n = 30) |

End of year

(n = 25) |

| Male | 36.7% | 40.0% |

| Female | 60.0% | 60.0% |

| Gender not stated | 3.3% | 0% |

| University of Auckland | 63.3% | 68.0% |

| University of Otago | 30.0% | 28.0% |

| Other University /

University not stated |

6.7% | 4.0% |

Table 3. Demographics of respondents (Overall)

Table 4 outlines the mean respondent rating for baseline and EOY survey items that were part of the Clinical Skills and Procedures section. When interpreting the table, the authors concluded that any items that fell below a mean of 2 at baseline were identified as warranting attention. Similarly, items that fell below 3 at the end of the PGY-1 year were identified as potential areas for concern.

| Clinical Task | Mean Response | ||

| Cardiopulmonary | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Perform 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) recording | 2.50 | 3.04 | .008* |

| Interpret a 12-lead ECG recording | 2.57 | 3.42 | .001* |

| Place a laryngeal mask airway | 2.27 | 2.38† | 1.000 |

| Place an oropharyngeal airway | 2.40 | 2.63† | .415 |

| Administer oxygen therapy | 2.70 | 3.63 | < .001* |

| Diagnostic | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Take blood cultures | 2.77 | 3.63 | <.001* |

| Test blood glucose levels | 3.17 | 3.42 | .073 |

| Get an accurate urine specimen | 2.67 | 3.13 | .030* |

| Take a nasal swab | 3.20 | 3.25 | .531 |

| Take a throat swab | 3.20 | 3.21 | .600 |

| Take a urethral swab | 2.17 | 2.52† | .189 |

| Take a wound swab | 2.90 | 3.50 | .015* |

| Ear Nose Throat | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Insert an anterior nasal pack | 1.20†† | 1.42†† | .617 |

| Perform anterior rhinoscopy | 1.10†† | 1.25†† | .488 |

| Injections | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Administer intramuscular injections | 2.77 | 3.08 | .064 |

| Administer subcutaneous injections | 2.27 | 2.91† | .006* |

| Intravenous/Intravascular | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Take an venous or / and arterial blood gas specimen (sampling) | 2.33 | 3.76 | <.001* |

| Arrange a blood transfusion | 1.67†† | 3.63 | <.001* |

| Perform intravenous cannulation | 3.00 | 3.61 | .001* |

| Administer appropriate intravenous electrolytes | 2.07 | 3.58 | <.001* |

| Administer appropriate fluids and drugs intravenously | 2.07†† | 3.42 | <.001* |

| Set up an intravenous infusion | 1.93†† | 2.54† | .011* |

| Perform venepuncture | 3.20 | 3.71 | <.001* |

| Mental Health | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Use the Alcohol Withdrawal rating scale | 1.47†† | 2.63† | .001* |

| Ophthalmic | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Remove a corneal foreign body | 0.90†† | 0.92†† | .627 |

| Apply an eye bandage | 1.30†† | 1.29†† | .783 |

| Administer eye drops | 2.53 | 2.83† | .242 |

| Irrigate an eye | 1.90†† | 2.04† | .495 |

| Evert an eyelid | 1.63†† | 1.79†† | .374 |

| Respiratory | Baseline | EOY | P |

| Set up and administer inhaler / nebuliser therapy | 1.97†† | 2.54† | .006* |

| Measure peak flow | 3.03 | 3.38 | .085 |

| Interpret peak flow findings | 2.60 | 3.13 | .015* |

| Measure spirometry | 1.70†† | 2.42† | .032* |

| Interpret spirometry findings | 2.13 | 2.71† | .007* |

| Surgical | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Administer local anaesthesia | 2.59 | 3.17 | .008* |

| Scrub up, gown and glove | 3.52 | 3.79 | .052 |

| Excise simple skin lesions | 2.45 | 2.83† | .170 |

| Tie surgical knots and suture a simple wound | 2.83 | 3.21 | .059 |

| Debride a wound | 2.10 | 2.58† | .041* |

| Dress a wound | 2.38 | 2.96† | .012* |

| Trauma | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Apply a splint or sling | 1.93†† | 2.17† | .065 |

| Apply a cervical collar | 1.90†† | 2.21† | .047* |

| Perform in-line immobilisation of the spine | 1.48†† | 2.17† | .014* |

| Provide pressure haemostasis | 2.38 | 3.33 | <.001* |

| Urogenital | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Catheterise the female bladder | 2.10 | 2.88† | .008* |

| Catheterise the male bladder | 2.56 | 3.75 | <.001* |

| Women’s Health | Baseline | EOY | p |

| Take a genital or cervical swab | 2.72 | 3.08 | .180 |

| Perform speculum examination of the vagina and cervix. | 2.79 | 2.67† | .392 |

| †† mean < 2

† mean < 3 (EOY only) * p < .05 |

|||

Table 4. Baseline and End of Year (EOY) self-rated competence level (clinical skills and procedures)

At the start of the PGY-1 year, the new doctors were most confident in their ability to scrub up, gown and glove (3.52) and this improved at EOY (3.79). This was followed by confidence in performing less invasive procedures like taking nasal/throat swabs and performing venepuncture. At EOY, taking venous or arterial blood, arranging a blood transfusion, performing intravenous cannulation and administering appropriate intravenous electrolytes scored above 3.5 indicating high clinical confidence levels. Male bladder catheterisation also scored highly at EOY (3.75).

Of the 48 clinical procedures listed, 34 (70.8%) were rated above 2.0 indicating that they had received satisfactory skill training in that procedure during undergraduate training. In the EOY survey, 43 out of 48 (90%) procedures were performed above the score of 2.0. However, the authors considered that by the end of the PGY-1 year doctors should be performing at a score of 3 indicating that multiple opportunities for practice of the skill had existed during the PGY-1 year and that they were confident performing the procedure independently. Twenty five of the 48 procedures (i.e. 52%) scored confidence levels above the score of 3. Low scores tended to occur in the following categories; Ear Nose and Throat (ENT), Ophthalmic, Surgical (more specifically, excising simple lesions, deriding and dressing a wound) and Trauma.

Analyses of the baseline and EOY results by gender, and by university attended were also conducted (Table 5). No gender differences were observed at baseline for any of the clinical competencies. However, four items did show significant gender differences in the EOY results. These were: Perform anterior rhinoscopy (p = .031), Administer eye drops (p = .019), Catheterise the female bladder (p = .042) and Perform speculum examination of the vagina and cervix (p = .002). Males rated themselves more competent in the first two items (although low overall), and females rated themselves more competent with the latter two items.

| Clinical Task | Mean Response | ||||||||||||||

| Baseline | End of Year | Baseline | End of Year | ||||||||||||

| Cardiopulmonary | Male | Female | Male | Female | Auckland | Otago | Auckland | Otago | |||||||

| Perform 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) recording | 2.45 | 2.44 | 2.90 | 3.14 | 2.58 | 2.22 | 3.06 | 2.86 | |||||||

| Interpret a 12-lead ECG recording | 2.73 | 2.44 | 3.70 | 3.21 | 2.53 | 2.56 | 3.44 | 3.43 | |||||||

| Place a laryngeal mask airway | 2.27 | 2.28 | 2.40 | 2.36 | 2.16 | 2.56 | 2.38 | 2.57 | |||||||

| Place an oropharyngeal airway | 2.45 | 2.39 | 2.60 | 2.64 | 2.47 | 2.44 | 2.75 | 2.57 | |||||||

| Administer oxygen therapy | 3.00 | 2.56 | 3.60 | 3.64 | 2.79 | 2.56 | 3.50 | 3.86 | |||||||

| Diagnostic | |||||||||||||||

| Take blood cultures | 2.27 | 3.00 | 3.50 | 3.71 | 2.42* | 3.33* | 3.44 | 4.00 | |||||||

| Test blood glucose levels | 3.09 | 3.17 | 3.30 | 3.50 | 3.16 | 3.11 | 3.31 | 3.57 | |||||||

| Get an accurate urine specimen | 2.27 | 2.94 | 2.70 | 3.43 | 2.68 | 2.78 | 3.00 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Take a nasal swab | 3.27 | 3.11 | 3.20 | 3.29 | 3.32 | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Take a throat swab | 3.45 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 3.29 | 3.37 | 2.89 | 3.19 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Take a urethral swab | 2.36 | 2.11 | 2.56 | 2.50 | 2.16 | 2.33 | 2.40 | 2.71 | |||||||

| Take a wound swab | 2.91 | 2.89 | 3.60 | 3.43 | 3.16 | 2.33 | 3.44 | 3.57 | |||||||

| Ear Nose Throat | |||||||||||||||

| Insert an anterior nasal pack | 1.45 | 1.06 | 1.90 | 1.07 | 1.37 | 0.78 | 1.69 | 0.86 | |||||||

| Perform anterior rhinoscopy | 1.55 | 0.83 | 1.80* | 0.86* | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.31 | 1.29 | |||||||

| Injections | |||||||||||||||

| Administer intramuscular injections | 2.64 | 2.83 | 3.20 | 3.00 | 2.68 | 2.78 | 2.88 | 3.43 | |||||||

| Administer subcutaneous injections | 2.18 | 2.33 | 3.10 | 2.77 | 2.21 | 2.22 | 2.80 | 3.00 | |||||||

| Intravenous/Intravascular | |||||||||||||||

| Take an venous or / and arterial blood gas specimen (sampling) | 2.36 | 2.33 | 3.80 | 3.71 | 2.32 | 2.44 | 3.69 | 3.86 | |||||||

| Arrange a blood transfusion | 1.73 | 1.61 | 3.70 | 3.57 | 1.58 | 1.78 | 3.50 | 4.00 | |||||||

| Perform intravenous cannulation | 2.91 | 3.00 | 3.60 | 3.61 | 2.63* | 3.56* | 3.40 | 4.00 | |||||||

| Administer appropriate intravenous electrolytes | 1.91 | 2.17 | 3.70 | 3.50 | 2.05 | 1.89 | 3.44 | 4.00 | |||||||

| Administer appropriate fluids and drugs intravenously | 2.09 | 2.06 | 3.60 | 3.29 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.31 | 3.57 | |||||||

| Set up an intravenous infusion | 1.64 | 2.11 | 2.30 | 2.71 | 1.84 | 1.89 | 2.44 | 2.57 | |||||||

| Perform venepuncture | 2.82 | 3.39 | 3.60 | 3.79 | 2.84* | 3.78* | 3.56 | 4.00 | |||||||

| Mental Health | |||||||||||||||

| Use the Alcohol Withdrawal rating scale | 1.27 | 1.61 | 2.70 | 2.57 | 1.53 | 1.44 | 2.50 | 3.00 | |||||||

| Ophthalmic | |||||||||||||||

| Remove a corneal foreign body | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 1.14 | |||||||

| Apply an eye bandage | 1.18 | 1.39 | 1.50 | 1.14 | 1.53 | 0.89 | 1.31 | 1.43 | |||||||

| Administer eye drops | 2.64 | 2.56 | 3.30* | 2.50* | 2.74 | 2.44 | 2.88 | 2.86 | |||||||

| Irrigate an eye | 2.27 | 1.72 | 2.50 | 1.71 | 2.26 | 1.33 | 2.19 | 2.00 | |||||||

| Evert an eyelid | 1.82 | 1.56 | 1.90 | 1.71 | 1.79 | 1.44 | 1.75 | 2.00 | |||||||

| Respiratory | |||||||||||||||

| Set up and administer inhaler / nebuliser therapy | 1.82 | 2.00 | 2.40 | 2.64 | 2.05 | 1.67 | 2.50 | 2.57 | |||||||

| Measure peak flow | 3.18 | 2.89 | 3.40 | 3.36 | 3.11 | 2.89 | 3.38 | 3.71 | |||||||

| Interpret peak flow findings | 2.55 | 2.61 | 3.20 | 3.07 | 2.42 | 3.00 | 3.06 | 3.43 | |||||||

| Measure spirometry | 1.82 | 1.61 | 2.40 | 2.43 | 1.84 | 1.33 | 2.25 | 3.00 | |||||||

| Interpret spirometry findings | 2.45 | 1.89 | 2.90 | 2.57 | 1.84 | 2.67 | 2.56 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Surgical | |||||||||||||||

| Administer local anaesthesia | 2.82 | 2.35 | 3.40 | 3.00 | 2.47 | 2.67 | 3.00 | 3.43 | |||||||

| Scrub up, gown and glove | 3.27 | 3.71 | 3.70 | 3.86 | 3.37* | 3.89* | 3.75 | 3.86 | |||||||

| Excise simple skin lesions | 2.55 | 2.41 | 3.10 | 2.64 | 2.37 | 2.67 | 2.69 | 3.14 | |||||||

| Tie surgical knots and suture a simple wound | 3.18 | 2.59 | 3.50 | 3.00 | 2.68 | 3.11 | 2.94* | 3.71* | |||||||

| Debride a wound | 2.18 | 2.06 | 3.10 | 2.21 | 2.16 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 2.86 | |||||||

| Dress a wound | 2.45 | 2.29 | 3.20 | 2.79 | 2.42 | 2.22 | 2.75 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Trauma | |||||||||||||||

| Apply a splint or sling | 1.91 | 1.94 | 2.40 | 2.00 | 1.89 | 2.00 | 2.19 | 2.29 | |||||||

| Apply a cervical collar | 2.00 | 1.82 | 2.40 | 2.07 | 1.79 | 2.11 | 2.25 | 2.29 | |||||||

| Perform in-line immobilisation of the spine | 1.45 | 1.41 | 2.10 | 2.21 | 1.21 | 1.89 | 2.00 | 2.71 | |||||||

| Provide pressure haemostasis | 2.18 | 2.47 | 3.40 | 3.29 | 2.32 | 2.44 | 3.31 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Urogenital | |||||||||||||||

| Catheterise the female bladder | 1.91 | 2.24 | 2.30* | 3.29* | 1.95 | 2.44 | 2.50* | 3.57* | |||||||

| Catheterise the male bladder | 2.55 | 2.53 | 3.80 | 3.71 | 2.42 | 2.78 | 3.63 | 4.00 | |||||||

| Women’s Health | |||||||||||||||

| Take a genital or cervical swab | 2.55 | 2.82 | 2.70 | 3.36 | 2.52 | 3.11 | 2.94 | 3.29 | |||||||

| Perform speculum examination of the vagina and cervix. | 2.55 | 3.00 | 1.90* | 3.21* | 2.68 | 3.11 | 2.38 | 3.14 | |||||||

| * p < .05 | |||||||||||||||

Table 5. Baseline and EOY self-rated competence level by gender and university attended

With regards to university attended prior, statistical significance was shown for four items at baseline. These were: Take blood cultures (p = .022), Perform intravenous cannelation (p = .005), Perform venepuncture (p = .042) and Scrub up, gown and glove (p = .048). In all four cases, the University of Otago graduates rated themselves more competent than their University of Auckland counterparts. By EOY, the difference between the university groups for these four items were non-significant (p > .05). However, three of the nine Otago graduates did not complete the EOY survey and therefore these results should be interpreted with caution.

IV. DISCUSSION

The terms “clinical confidence” and “competence” were employed cautiously in this study recognising that confidence was not necessarily a marker for competence and that only standardised assessment could verify actual competence (Stewart et al., 2000).

When comparing the two surveys, three trends emerged across the grouped categories. These were areas where clinical confidence:

1. was high at both points i.e. pre- and post-PGY-1 (e.g., cardiopulmonary, diagnostic and surgical),

2. was not high at baseline, but showed significant improvement by year-end (e.g. intravenous/intravascular) and,

3. remained low at both baseline and EOY (e.g., ENT, ophthalmic).

Our results indicate that PGY-1 doctors may not be receiving adequate training in the list of procedural skills during the PGY-1 year and it would be imperative that clinical supervisors continue to focus on this attainment during the PGY-2 year. The study showed that they rated their inability to perform 48% of the clinical skills at a level of independence in most settings.

PGY-1 confidence in performing ENT and ophthalmic procedures remained low (<2) throughout the year. This suggested that the undergraduate programme was not adequately addressing the learning of these procedural skills, nor were they having the opportunities during the PGY-1 year to improve their skills in these areas. In contrast, while the students were poorly confident about their intravenous/intravascular skills at baseline, these skills improved during the PGY-1 year to a level of being capable of performing them independently.

Of concern is the drop in clinical confidence in performing speculum examination of the vagina and cervix. While developing a clinical skill is important, maintenance of that skill is equally important during the prevocational years. Further analysis of this item by gender found that PGY-1 males’ clinical confidence dropped from 2.55 to 1.90, whereas females’ confidence levels increased from 3.00 to 3.21. Connick, Connick, Klotsas, Tsagkaraki, and Gkrania-Klotsas (2009) identified procedural confidence as dependent on gender just as it was on being offered the opportunity for gaining experience. This item, and female bladder catheterisation, was rated significantly lower by males at EOY, which may suggest a lack of confidence with gender-specific procedures.

Some differences were found between the two main medical school graduates with respect to four items at the beginning of the PGY-1 year. The subsequent EOY survey indicated that these differences had vanished by year-end. However, it should be noted that a third of the Otago graduates, did not complete the EOY survey, so these results need to be interpreted with caution. It is also difficult to generalise our findings to the wider medical school graduate population given that approximately 150-180 students graduate from Auckland, and 210-230 students from Otago each year. A nationwide study of this sort would however provide insight into both whether the differences we observed are part of a national trend, and whether these differences have tapered off by the end of the PGY-1 year. Such information would provide useful feedback for the institutions involved.

The study did not address the association of clinical confidence in performing clinical skills and the types of clinical attachments completed during the PGY-1 year and whether these influenced the final results. This study also did not measure clinical confidence after the PGY-2 years. A proportion of the PGY-2 doctors are likely to complete clinical attachments in ENT, Ophthalmology and the Emergency Department which may allow for experience in competencies that scored low at the start and end of the PGY-1 year. Given the relatively small size of these departments, it would be unlikely that many PGY-2 doctors will rotate through these departments and therefore experience in performing these procedures would remain low. It is therefore vital that College training programmes that require the competent performance of these procedural skills ensure that vocational trainees receive adequate training (e.g. with the Royal New Zealand College of General Practice (RNZCGP)). A longitudinal-based study, similar in design to the current study could measure changes in clinical confidence at not only the beginning and end of PGY-1; but also at further time points (e.g., at the end of the PGY-2 year and the end of the first year of registrar training). This would provide valuable feedback for the above training colleges.

V. CONCLUSION

The skills survey conducted was designed as a self-assessment tool of how competent PGY-1s felt they were in regard to specific clinical skills and procedures. These procedures are outlined in the NZCF as core procedures and interventions that PGY-1s should be able to perform at the end of the PGY-1 year, while “…recognising the limits of their personal capabilities” (MCNZ, 2014). Our findings show that while this benchmark has been achieved in some fields, there are other areas lacking, which may be due to the lack of exposure in certain specialties in the PGY-1 year. Our concern is that competence in these procedures will remain low through the PGY-2 year and possibly as far as vocational training level, once again due to little practical involvement. This paper, and future longitudinal and / or nation-wide studies may therefore serve to inform current undergraduate curriculum planning at the medical school level, as well as provide feedback to the New Zealand Medical Council on the current level of PGY-1 confidence in the core clinical skills and procedures identified by the NZCF.

Notes on Contributors

Dr Wayne de Beer works as a specialist in Consultation-Liaison psychiatry and work part-time as a Clinical Training Director at the Clinical Education & Training Unit; Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand. His focus is largely on the prevocational and vocational medical training periods. Publications have included medical education and psychiatry.

Ms Helen Clark is the Medical Education Officer based in the Clinical Education & Training Unit at Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand. Her background includes research and statistical analysis in the fields of medical education and psychology. She has academic publications in both fields.

Ethical Approval

A determination of the need for formal ethical approval was sought from the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (HDEC). The study was deemed by HDEC to meet the criteria of observational research, therefore did not require formal ethics approval, due to meeting guidelines around health information, human tissue and human participants, as outlined in the HDEC scope summary (Health and Disability Ethics Committee, 2016). The study was registered with Waikato DHB’s internal research committee.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Carol Stevenson, Personal Assistant to the Director of Clinical Training, at the Clinical Education and Training Unit at Waikato DHB, for the development and facilitation of the PGY-1 NZCF Procedural skills and communications Competencies Measure survey tool.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declared no competing interest.

References

Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley.

Byrne, A. J., Blagrove, M. T., & McDougall, S. J. (2005). Dynamic confidence during simulated clinical tasks. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 81(962), 785-788.

Connick, R. M., Connick, P., Klotsas, A. E., Tsagkaraki, P. A., & Gkrania-Klotsas, E. (2009). Procedural confidence in hospital based practitioners: implications for the training and practice of doctors at all grades. BMC Medical Education, 9, 2.

Evans, J., Bell, J. L., Sweeney, A. E., Morgan, J. I., & Kelly, H. M. (2010). Confidence in Critical Care Nursing. Nursing Science Quarterly, 23, 334.

Fitzgerald, J. T., White, C. B., & Gruppen, L. D. (2003). A longitudinal study of self-assessment accuracy. Medical Education, 37, 645-649.

Hays, R. B., Jolly, B. C., Caldon, L. J., McCrorie, P., McAvoy, P. A., McManus, I. C., & Rethans, J. J. (2002). Is insight important? Measuring capacity to change performance. Medical Education, 36(10), 965-971.

Health and Disability Ethics Committee. (2016). Applying for review; does your research require HDEC review? Retrieved from http://ethics.health.govt.nz/applying-review.

Medical Council of New Zealand. (2014). New Zealand Curriculum Framework for Prevocational Medical Training. Retrieved from https://www.mcnz.org.nz/assets/News-and-Publications/NZCF26Feb2014.pdf.

Miller, G. E. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic medicine, 65(9), S63-7.

Patel, M., Oosthuizen, G., Child, S., & Windsor, J. A. (2008). Training effect of skills courses on confidence of junior doctors performing clinical procedures. New Zealand Medical Journal, 121(1275), 37-45.

Stewart, J., O’Halloran, C., Barton, J. R., Singleton, S. J., Harrigan, P., & Spencer, J. (2000). Clarifying the concepts of confidence and competence to produce appropriate self-evaluation measurement scales. Medical Education, 34(11), 903-909.

*Dr Wayne de Beer

Tel: +64 7 8398899 ext 98399

Fax: +64 21 2232549

Email: Wayne.deBeer@waikatodhb.health.nz

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2018, 3(2), 25-28

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-2/OA1039

Pairoj Boonluksiri

Hatyai Medical Education Centre, Hatyai Hospital, Songkhla, Thailand

Abstract

Background: Smartphones are used worldwide. Consequently, it does seem to be having an impact on health-related problems if overused. However, it is uncertain whether it is associated with sleep problems or poor learning.

Objective: To determine the association between smartphone overuse and sleep problems in medical students as primary outcome and poor learning as secondary outcome

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in 89 students having their own smartphones, at Hatyai Medical Education Centre, Thailand. The habits of using smartphone were obtained. Smartphone overuse during bedtime was defined as using longer than 1 hour according to Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). The primary outcome was napping in a classroom that was defined as a problem if it happened more than 20% of the time attending class. Sleep problems using Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) were obtained by self-assessment. Learning outcome measured by grade point average was the secondary outcome. Multivariable analysis was performed for the association between smartphone overuse and sleep problems.

Results: Of all students, 77.5% had sleep problems and 43.6% had napped in the classroom No personal characteristics, daily life behaviours, and physical environments were associated with sleep problems. 70.8% of all students found to over use smartphones during bedtime. The Facebook website was the most popular. Smartphone overuse was significantly associated with poor sleep quality (odds ratio= 3.46) and napping in the classroom (odds ratio=4.09) but not grade point average.

Conclusion: Smartphone overuse during bedtime in medical students is associated with sleep problems but not learning achievement.

Keywords: Napping in Classroom, Sleep Problems, Smartphone Overuse

Practice Highlights

- The smartphone is a useful and essential tool for communication, it should be used smartly for appropriate purposes.

- Smartphone overuse during bedtime has a significant effect on sleep quality and consequently napping in the classroom.

- No significant association between smartphone overuse and learning outcome was found.

I. INTRODUCTION

Smartphones are now used in everyday life and offer a substantial variety of mobile applications for information, communication, education, and entertainment purposes. Most students also use them for hours and some tend to have the addiction to smartphones. By the Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS), the incidence of smartphone addiction is as high as 16.9% and the duration of smartphone screen-time increases the incidence of addiction (Haug et al., 2015). Based on the definition of internet addiction, smartphone overuse may disturb users’ daily lives such as learning performance and sleep quality. College students spent almost nine hours daily on their cell-phones (Roberts, Yaya, & Manolis, 2014). Consequently, smartphones or computers have an impact on physical health-related problems such as blurred vision, myofascial pain syndrome at wrists and neck if overused (Ganeriwal, Biswas, & Srivastava, 2013). A previous survey of smartphone screen-time in general population showed that there was a significant association between screen time and poor sleep (Christensen et al., 2016). The prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness in medical students was reported as high as 30.6% (Ramamoorthy, Mohandas, Sembulingam, & Swaminathan, 2014). But it is uncertain regarding the association between smartphone overuse and sleep problems or poor learning. The objective of this study is to determine the association between smartphone overuse and sleep problems in medical student as primary outcome and poor learning as a secondary outcome.

II. METHODS

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 89 Year-4 and Year-5 medical students at Hatyai Medical Education Centre, Thailand. All students having their own smartphones were included. Fifty-three students (58.4%) were male. Data were obtained using a questionnaire for student characteristics, habits of using a smartphone, self-assessment for sleep quality using Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and sleep problems using Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Recall information was filled out.

Smartphone overuse was defined as using longer than 1 hour during bedtime according to the previous study showing that it increased the incidence of smartphone addiction by Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS) (Haug et al., 2015). The primary outcome was collected as the incidence of napping in the classroom defined as a problem if it happened more than 20 percent of the numbers of total class attending. The numbers of classroom absences in each student were not counted in the total class attending for the denominator. However, there were only a few students who did not attend completely in every session due to personal reasons such as illness, but they attended more than 90% of all sessions.

Nap means to sleep for a brief period, often during the day; doze or to be unaware of imminent danger or trouble. Learning achievement using grade point average (GPA) in last academic year was a secondary outcome. Data analysis were performed using multivariable logistic regression to find out the association between smartphone overuse among sleep problems and GPA.

III. RESULTS

Most of the students use expensive smartphones. Sixty-five percent of students have phones costing more than 560 USD, 29.4% having phones costing 560-280 USD, the rest having phones costing less than 280 USD. They bought expensive smartphones because of more options and more attractive features. All of 66.7% medical students usually take them all day.

The survey of internet access showed that the top 5 favourite rankings were Facebook, phone calls, non-academic searching, academic searching and LINE chatting. The other option was taking a photograph. The common periods of using smartphone were 9 pm until after midnight, 6pm-9pm, and all day equal 41%, 38%, and 21% respectively. Most students sleep lately. All of 78.6% sleep after midnight.

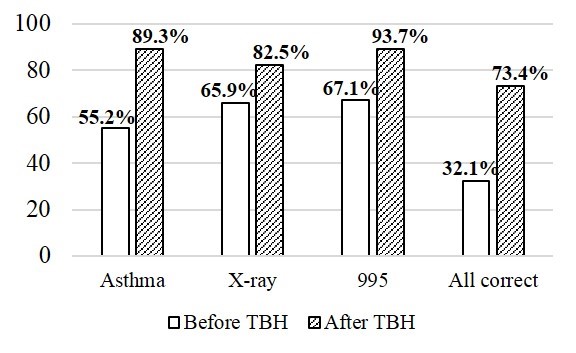

The mean duration of sleep at night was 2.3+1.1 hours. A total of 77.5% had sleep problems by ESS and 45% of these had poor sleep quality by PSQI. There were 63 cases (70.8%) having smartphone overuse more than 1 hour during bedtime. Consequent napping in the classroom was found as high as 43.6% (range 0-90) and was associated with smartphone overuse during bedtime significantly (p=0.004). No other student characteristics, daily life behaviours, and classroom environments were associated with napping (Table 1).

By multivariable analysis, napping in the classroom and poor sleep problems were associated with smartphone overuse significantly (odds ratio = 4.125 and 3.373 respectively) (Table 2). No significant association between smartphone overuse and short duration of night sleep less than 3 hours was found. The mean GPA was 3.25 (range 2.02-3.91). There was a high rate of smartphone overuse in an honour group with GPA more than 3.50 and low incidence of napping in the classroom. However, there was no statistically significant association between GPA and smartphone overuse.

| Student characteristics and behaviours | Category of sleepy in the classroom | p-value | |

| Normal

N=20 (%) |

Napping

N=69 (%) |

||

| Male | 9 (45) | 43 (62.3) | 0.166 |

| Body mass index | 21.46 | 21.37 | 0.866 |

| Smartphone overuse at bedtime | 9 (45) | 54 (78.3) | 0.004 |

| Tired with learning activities | 10 (50) | 36 (52.2) | 0.860 |

| Tired with extra-activities | 10 (50) | 36 (52.2) | 0.860 |

| Boring teachers | 11 (55) | 44 (63.8) | 0.477 |

| Stringent teachers | 5 (25) | 9 (13) | 0.196 |

| Environment factors | 13 (65) | 36 (52.2) | 0.310 |

| No breakfast | 4 (20) | 20 (28.9) | 0.428 |

| Too full stomach | 9 (45) | 19 (27.5) | 0.139 |

| Health problem | 1 (5) | 7 (10.1) | 0.479 |

| Sleep lately after midnight | 14 (70) | 56 (81.2) | 0.284 |

| Sedative medication | 2 (10) | 5 (7.2) | 0.687 |

| Too early morning class | 4 (20) | 19 (27.5) | 0.498 |

| Caffeine drinking >3 days/week | 12 (60) | 32 (46.4) | 0.283 |

| Exercise >3 days/week | 4 (20) | 24 (34.8) | 0.210 |

| Duration of night sleep (hours) | 2.4 | 2.2 |

0.254 |

Table 1. Comparison between napping in the classroom among student characteristics and behaviours by univariate analysis

| Smartphone overuse at bedtime and related variables | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

| Napping in the classroom | 4.125 | 1.265, 13.447 | 0.019 |

| Poor sleep quality by ESS | 0.914 | 0.245, 3.407 | 0.893 |

| Sleepy problems by PSQI | 3.373 | 1.123, 10.133 | 0.030 |

| Duration of night sleep | 0.835 | 0.518, 1.346 | 0.458 |

| Grade point average (GPA) | 1.515 | 0.440, 5.219 | 0.510 |

| Male | 0.535 | 0.176, 1.623 | 0.269 |

Table 2. Comparison between smartphone overuse among sleep characteristics and GPA by multivariable analysis

IV. DISCUSSION

Sleep problem is common in students including medical students. The prevalence of sleep problems varies from 17-70% and it was multifactorial such as poor sleep quality, inadequate sleep time, depression, fatigue etc. which is in accordance with this study for poor sleep (Azad et al., 2015).

Medical students in this study had inadequate sleep. Their sleep time duration were less 3-4 times than National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep time duration recommendations suggesting that 18-25 year olds should have a sleep duration about 7-9 hours (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). Abnormal ESS scores were associated with lower academic achievement (Hamza et al., 2012) however it was not found in this study. Previous studies showed some people having habits at bedtime such as reading, using a smartphone for relaxation. These behaviours have an effect on poor sleep quality and depression.

Smartphone overuse can lead to depression and anxiety, which can, in turn, result in sleep problems (Ahn & Kim, 2015; Alsaggaf, Wali, Alsager, Alkhammash, & Quqandi, 2014; Demirci, Akgönül, & Akpinar, 2015). University students with high depression and anxiety scores should be carefully monitored for smartphone addiction. Side effects of smartphone overuse such as a chronic headache, concentration problem, long-term memory problem, recent memory problem, insomnia and inadequate sleep have been reported among medical students (Abdulmohsen et al., 2016).

Caffeine and alcohol ingestion also affected sleep and daytime sleepiness. Sleep difficulties resulted in irritability and affected lifestyle and interpersonal relationships (Giri, Baviskar, & Phalke, 2013). This study could not find the association between smartphone overuse and learning outcome which is discordant with previous reports (Ahn, & Kim, 2015; Alsaggaf et al., 2014). It might be related to multifactorial and needs further study. The exact percentage of napping in the classroom in this study might be slightly overestimated if all students who attended only 90% of all sessions had no more napping in the classroom when they attended completely.

V. CONCLUSION

Smartphone overuse during bedtime in medical students has an association with sleep problems but not learning achievement.

Notes on Contributors

Pairoj Boonluksiri, a paediatric neurologist, works at Medical Education Centre, Hatyai Hospital, Thailand and is responsible for medical teacher and educator. Assessment is his favourite field in medical education. He has got a certificate of fellowship in medical education (assessment), at the University of Illinois at Chicago, the USA since 2003.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board for Human Research of Hatyai Hospital approved this study.

Declaration of Interest

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Abdulmohsen, A. A. J., Ahmed, R. A. F., Abdulaziz, A. H., Mahdi A. S., Abdulhameed A. L. K., & Sayed I. A. (2016). Patterns of use of ‘smartphones’ among male medical students at King Faisal University (KFU) and its side effects. International Journal of Science and Research, 5(10), 2319-7064.

Ahn, S.Y., & Kim, Y.J. (2015). The Influence of Smartphone Use and Stress on Quality of Sleep among Nursing Students. Indian Journal of Science & Technology, 8(35), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2015/v8i35/85943.

Alsaggaf, M., Wali, S., Alsager, A. B., Alkhammash, R., & Quqandi, E. (2014). Sleep disturbances among medical students at clinical years. European Respiratory Journal, 44, 2297.

Azad, M.C., Fraser, K., Rumana, N., Abdullah, A.F., Shahana, N., & Hanly, P.J. (2015). Sleep disturbances among medical students: a global perspective. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(1), 69–74.

Christensen, M. A., Bettencourt, L., Kaye, L., Moturu, S. T., Nguyen, K. T., Olgin, J. E., … Gregory, M. M. (2016). Direct measurements of smartphone screen time: Relationships with demographics and sleep. PLoS ONE, 11(11): e0165331. http:/dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0165331.

Demirci, K., Akgönül, M., & Akpinar, A. (2015). Relationship of smartphone use severity with sleep quality, depression, and anxiety in university students. Journal of Behavioural Addictions, 4(2), 85–92.

Ganeriwal A. A., Biswas D. A., Srivastava T. K. (2013). The Effects of Working Hours on Nerve Conduction Test in Computer Operators. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal, 7, 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.5704.MOJ.1303.008.

Giri, P. A., Baviskar, M. P., & Phalke, D. B. (2013). Study of sleep habits and sleep problems among medical students of Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences Loni, western Maharashtra, India. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, 3(1), 51–54.

Hamza, M., Abdulghani, A. A. A., Aorah, S. B. S., Nourah, M. A. S., Alhan, M. A. H. & Ali, I. A. (2012). Sleep disorder among medical students: Relationship to their academic performance. Medical Teacher, 34, S37–S41.

Haug S., Castro R.P., Kwon M., Filler A., Kowatsch T., & Schaub M.P. (2015). Smartphone use and smartphone addiction among young people in Switzerland. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(4), 299–307.

Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni O., DonCarlos, L., … Adams Hillard, P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s Sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1, 40–43.

Roberts, J. A., Yaya, L. H. P. & Manolis, C. (2014). The invisible addiction: Cell-phone activities and addiction among male and female college students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(4), 254–265.

Ramamoorthy, S., Mohandas, M., Sembulingam, P., & Swaminathan, V.R. (2014) Prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) among medical students. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 3(4), 1819-1826.

*Pairoj Boonluksiri, M.D.

Pediatric Department

Hatyai Medical Education Center

Hatyai Hospital

Songkhla 90110, Thailand

Email: bpairoj@gmail.com

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2018, 3(2), 19-24

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-2/OA1049

Rebecca Grainger1, Emma Osborne2, Wei Dai1 & Diane Kenwright1

1Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, University of Otago Wellington, New Zealand; 2Higher Education Development Centre, University of Otago, New Zealand

Abstract

Cognitively complex assessments encourage students to prepare using deep learning strategies rather than surface learning, recall-based ones. In order to prepare such assessment tasks, it is necessary to have some way of measuring cognitive complexity. In the context of a student-generated MCQ writing task, we developed a rubric for assessing the cognitive complexity of MCQs based on Bloom’s taxonomy. We simplified the six-level taxonomy into a three-level rubric. Three rounds of moderation and rubric development were conducted, in which 10, 15 and 100 randomly selected student-generated MCQs were independently rated by three academic staff. After each round of marking, inter-rater reliability was calculated, qualitative analysis of areas of agreement and disagreement was conducted, and the markers discussed the cognitive processes required to answer the MCQs. Inter-rater reliability, defined by the intra-class correlation coefficient, increased from 0.63 to 0.94, indicating the markers rated the MCQs consistently. The three-level rubric was found to be effective for evaluating the cognitive complexity of MCQs generated by medical students.

Keywords: Student-generated Multiple-choice Questions, Cognitive Complexity, Bloom’s Taxonomy, Marking Criteria, Moderation of Assessment

Practice Highlights

- Allow enough time for several cycles of moderation between markers, especially when the subject matter is complex. While other researchers have reported reaching a high level of inter-rater reliability swiftly, our research highlights that it can take time for teams to agree on a marking approach for complex, clinically-based questions.

- Guide students to write questions that require the information in the full stem to answer the question. We found that without additional guidance, students often wrote detailed clinical vignettes that were followed by straightforward recall-type questions.

- Minimise levels of complexity included in the rubric. We found three levels of complexity sufficient to make practical distinctions in the quality of students’ questions.

I. INTRODUCTION

Multiple choice questions (MCQs) are used widely in assessing medical education. Well-constructed MCQs can be valid and reliable assessment tools. (McCoubrie, 2004; Schuwirth & Van Der Vleuten, 2004). From a practical perspective, they are also reusable, easy to administer and easy to grade. While a recognized drawback of MCQs is that they tend to test memorization rather than analytical thinking (Schuwirth & Van Der Vleuten, 2004; Veloski, Rabinowitz, Robeson, & Young, 1999), it is possible to construct MCQs that do test students’ ability to apply knowledge and analyse problems (Khan & Aljarallah, 2011; McQueen, Shields, Finnegan, Higham, & Simmen, 2014; Palmer & Devitt, 2007). Given that students modify their study strategies in accordance with the complexity of thinking they anticipate needing to use in summative assessment (Biggs, 1999; Scouller & Prosser, 1994), one challenge for medical educators is to develop cognitively complex MCQs that will foster the kind of analytical reasoning that students will need in their medical careers.

One facet of improving MCQs is developing clear guidelines for items that require cognitively complex thinking as well as memorization. This requires a framework for classifying the thinking needed to answer MCQs. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Bloom, 1956) and the subsequent revision of Bloom’s taxonomy (Krathwohl, 2002) are popular starting points for classifying MCQ (Bates, Galloway, Riise, & Homer, 2014; Buckwalter, Schumacher, Albright, & Cooper, 1981; Khan & Aljarallah, 2011; McQueen et al., 2014; Palmer & Devitt, 2007; Rush, Rankin, & White, 2016). However, the majority of these papers tend to describe the process of rating MCQs using such a taxonomy very briefly, perhaps implying that the act of categorizing questions can be assumed to be intuitive and straightforward. Yet when we attempted to score MCQs using a Bloom-derived taxonomy, we initially found it difficult to translate a theoretical approach to cognitive complexity into a practical marking guide.

Medical students at the University of Otago were tasked with writing case-based MCQs for topics in pathology. The purpose of this task was to engage students in deep, clinically relevant learning in a way that also fulfilled their need for material that prepared them for the end-of-year MCQ examination (Grainger, Dai, Osborne, & Kenwright, 2017). Our research team then developed a rubric to evaluate the cognitive complexity of these student-generated MCQs, and this paper reports this process of rubric development. We initially found a high level of disagreement between markers as to how questions should be scored, evidenced by a low level of inter-rater reliability. Through analyzing the cognitive processes required to answer the questions and revising our marking criteria, we subsequently achieved a high level of inter-rater reliability. This paper argues that assessing MCQs for cognitive complexity based on existing taxonomies is an achievable task for a non-specialist team and reports our process of developing marking criteria as a model for other teams attempting a similar task.

II. METHODS

The student-generated MCQ approach was used in four modules (cardiovascular, central nervous system, respiratory and gastrointestinal) of an anatomic pathology course at the University of Otago. One hundred and six fourth-year medical students were enrolled in the PeerWise platform, in which students create MCQs and answer questions that their peers have created. (University of Auckland, 2016). For each topic, each student was required to create at least two MCQs similar to those found in their end-of-year exam, each comprising a stem (case scenario with question), one correct answer and three or four plausible distractors.

A rubric based on Bloom’s Taxonomy for evaluating the quality of these MCQs was developed over three iterations. The highest level of Bloom’s taxonomy, synthesis, was not included in the rubric as it is not applicable to a pre-defined task such as writing MCQs. In the first round of moderation, 10 out of 201 MCQs were randomly selected and independently rated by three markers. Results were then shared between raters, and one of the raters (EO) identified patterns of agreement and disagreement using summative content analysis of keywords and phrases that indicated the steps the respondent needed to undertake to answer the question (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Following this analysis, MCQs that were representative of issues the markers disagreed were circulated between the team members. These questions were used as a starting point for structured conversations where each rater described the process that they had used to mark to the question. Then a subset of 15 out of 331 MCQs, followed by a further 100 out of 678 MCQs were rated, analysed and discussed in the same manner. After each round of moderation, the inter-rater reliability was determined by calculating the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) (Bartko, 1976). Three staff participated the rating process. One had content expertise (RG), while the other two had backgrounds in higher education (WD, EO). The project had ethical approval from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (D16/423).

III. RESULTS

After the first round of marking, there was a low level of inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.543, 95% CI -0.668-0.912), suggesting raters were inconsistent in assigning the MCQs to levels in the six-level rubric. There was high level of agreement among raters about whether certain types of question should be classified as cognitively complex or not. For example, all raters marked questions requiring recall or comprehension of factual knowledge lower than questions required the respondent to make a diagnosis based on a clinical scenario (see Figure 1). However, raters were inconsistent on which level a question should fall within the low-order thinking category (i.e. recall or comprehension) and within the high-order thinking category (i.e. application, analysis or evaluation). As the aim of the task was to foster cognitively complex questions, we condensed Bloom’s recall and comprehension levels into a single level. In line with literature indicating that analysis and evaluation frequently overlapped (Moseley et al., 2005) we condensed these two categories into one level, while retaining the distinction between application and analysis.

The inter-rater reliability slightly increased in the second round of marking using the simplified rubric (ICC = 0.62, 95% CI 0.105-0.869). Content analysis of characteristics of inconsistently marked MCQs showed that marking varied for clinical case-based MCQs. Some MCQs had recall-based questions nested within a stem that superficially featured a clinical case, and markers agreed after discussion that these should be treated as recall/comprehension questions (see Figure 2).

| Which of the following is not a feature of infiltrating astrocytomas?

A. It accounts for around 80% of adult primary brain tumours. B. High grade lesions have leaky vessels that exhibit contrast enhancement on imaging. C. The transition from normal to neoplastic cells is indistinct. D. Microscopically psammonoma bodies can be seen. Marker comment: This question lacks a clinical scenario that would require the respondent to apply their knowledge to a real-life problem. To answer the question, the respondent needs to recall factual information associated with the condition and to understand aspects of the condition’s appearance. |

Figure 1. Question testing recall/comprehension without a clinical case in the stem

Note: Questions have been lightly edited for clarity and brevity (abbreviations expanded and extraneous description removed) but otherwise left as written by the students, reflecting understanding of pathology at a fourth year medical student level. Author’s chosen correct answer is indicated in italics.

| A 27-year-old man is rushed into the Emergency department after suddenly collapsing during a marathon run. Upon examination, the patient is found to have a heart rate of 110 bpm, a blood pressure of 70/50 mmHg, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute and temperature 36.7° C. A CT scan is ordered, and show a diagnosis of an aortic dissection. Which one of the following statements is false?

A. Because the patient is hypotensive, the aortic dissection is likely to be a group B aortic dissection according to the Stanford classification. B. A normal 12-lead ECG (not including the tachycardic rate) in this patient would be consistent with the diagnosis. C. The young age of the patient suggests Marfan’s syndrome is a possible factor. D. A finding of a difference in blood pressure greater than 20 mmHg between the right and left upper limbs contradicts the diagnosis. Marker comment: Although the question includes a clinical scenario in the stem, it does not require the respondent to use this information because the diagnosis is stated in the stem. The possible answers include statements that test recall and basic comprehension of facts associated with the condition. |

Figure 2. Recall/comprehension question nested in a clinical stem

There was an unclear boundary between application and analysis/evaluation. In the subsequent discussion, we agreed that questions where the respondent needed to choose a diagnosis from a straightforward list of symptoms should be classified as application (see Figure 3).

|

A 20-year old New Zealand European male presents with a three-day history of macroscopic haematuria, low grade fever and loin pain. He is otherwise well. He experienced a similar episode of haematuria with no other symptoms about a year prior, which resolved spontaneously. His uncle had his gallbladder removed but his family is otherwise well. He not taking any regular medicines. Observations: HR 64, BP: 140/90, RR: 18, Temp: 37.6. What is the most likely diagnosis and management? A. Pyelonephritis. Provide supportive care and discharge. B. Cystic cancer. Requires radical cystectomy. Refer to surgeons immediately C. IgA nephropahty. Discharge to outpatient clinic for biopsy, conduct immunofluorescence. Start ACE inhibitor if appropriate. D. Post strep glomerulonephritis. Start methotrexate immediately. Marker comment: This question requires the respondent to apply their knowledge of the condition to make a likely diagnosis from signs and symptoms, then to recall appropriate treatment. The respondent could also answer the question by excluding incorrect combinations of conditions and treatments, which would draw on a subset of classifying/categorizing. |

Figure 3. Question testing application of knowledge

We classified as analysis/evaluation questions which required the respondent to combine and interpret multiple forms of information or to anticipate other findings associated with a condition. For example, some questions required the respondent to predict likely test results from presenting symptoms, or combine and weight the importance of different sets of observations (see figure 4). Based on this discussion, specific explanations of each level of the simplified rubric in the context of medical education were generated and incorporated into the rubric (Table 1).

A high inter-rater reliability was shown in the third iteration using the simplified and redefined rubric (ICC= 0.89, 95% CI 0.845-0.923), suggesting that raters were assessing MCQs in a consistent way. Raters also reported improved time efficiency using the new rubric compared to the first two iterations.

|

Mr. S is a 53-year-old male who presents to you, his general practitioner, with lethargy for the last 6 months that he feels is out of the ordinary. He says his wife thinks his face is puffier than usual, and he has also developed some acne which he has not had since he was a teenager. He has also been experiencing shortness of breath at rest, and has had a persistent cough of for the last 3 months. He is a now a non-smoker but has a 20 pack year history. He has a BMI of 24, and has never had diabetes. You order a CXR which shows a central hilar mass. You refer him to Wellington hospital to get a biopsy which is examined by the pathologist. What would the expected microscopic findings be? A. Hyperchromatic, pleomorphic, mitotically active glandular cells with areas of necrosis. B. Small blue cells with little cytoplasm, crush artefact, and containing neurosecretory granules C. Sheets of hyperchromatic, pleomorphic, mitotically active cells with keratin whorls. D. Glandular tissue with goblet cell atrophy and neoplastic change. Marker comment: The question requires the respondent to analyse and combine several sources of information (signs and symptoms, history and x-ray results) to form a possible diagnosis, then to anticipate and interpret the likely microscopic findings for this diagnosis. |

Figure 4. Question testing analysis/evaluation of knowledge

| Level | Corresponds to Bloom’s Taxonomy | Description |

| Level 1 | Recall & comprehension | Knowing and understanding facts about a disease,

classification, signs & symptoms, procedures, tests. |

| Level 2 | Application | Applying information about a patient (signs & symptoms, demographics, behaviours) to solve a problem (diagnose, treat, test) |

| Level 3 | Analysis & evaluation | Using several different pieces of information about a patient to understand the whole picture, combining information to infer which is most probable. |

Table 1. Rubric with categorization levels and explanations for the cognitive domain

IV. DISCUSSION

Student-generated, cognitively complex MCQs help prepare medical students for examinations which include these question types. This paper addresses the extent to which classifying questions by cognitive level is reliable, valid and practical. It also indicates a need for future research into how best to guide students in developing sophisticated MCQs.

We found our final rubric to be a reliable measure of question complexity, as evidenced by the high level of inter-rater reliability. The difficulties we found in drawing distinctions between levels of complexity were largely consistent with the challenges and possible solutions identified previously. For example, a lack of clarity in the top levels of Bloom’s taxonomy reflects other work suggesting that modelling the higher order skills hierarchically may not be appropriate. One major revision of the taxonomy reverses the order of the upper levels (Krathwohl, 2002) and other critics have suggested that the differences between higher order skills are not clear cut and that ranking these skills is somewhat arbitrary (Moseley et al., 2005). While some have attempted to argue that MCQs can draw on thinking skills at all levels (Bloom, 1956; Young & Shawl, 2013), these appear to either: relate to questions that would only require evaluative thinking if reasoned from first principles in the exam rather than memorized (Young & Shawl, 2013); or be MCQs asked in relation to an extended problem rather than containing all the necessary information within the stem (Bloom, 1956). In developing our rubric, we selected levels of cognition similar to other researchers (Rush et al., 2016; Vanderbilt, Feldman, & Wood, 2013), although we combined comprehension with recall rather than application, as some others have done (Khan & Aljarallah, 2011; Palmer & Devitt, 2007). This suited our purposes in assessing a subject with a very strong applied component, where there was a crucial and clear difference between understanding the salient features of a condition and being able to apply that knowledge to a clinical scenario. The performance and utility of the rubric will need to be determined in other MCQ sets.

The difficulty we experienced in deciding how complex questions were does not appear to have been reported elsewhere; it is possible that this process is more difficult with highly involved clinical questions or that other authors have chosen not to focus on this area. One paper that does utilize Bloom’s taxonomy in rating student-generated physics MCQs found a high level of inter-rater reliability in marking questions (Bates et al., 2014). Despite this, the authors do note a similar issue to us in that they comment that it was easier to rate lower-order questions than to make distinctions between application and analysis. Here it is likely that the subject material could influence the ease of marking. Bates et al. (2014) rated students’ physics MCQs, and it may be that it was easier to identify, for example, whether single- or multiple-step mathematical calculations were required in these kinds of problems than identify the thought processes associated with clinical scenarios in our research.

In terms of the practicality of our rubric, we found that the clearly redefined rubric was effective in simplifying the rating process and reducing rating time. For non-content experts, the new rubric has enabled them to judge the level of cognitive effort at the same level as a content expert.

A final and not fully resolved question is how best to guide students in writing complex, scenario-based MCQs. Our larger research project found that students tended not to utilise theoretical guidance on using a model such as Bloom’s Taxonomy in developing their MCQs (Grainger et al., 2017). We therefore intend to develop a more concrete, example-based scaffold for item-writing and assess whether students produce a similar quality of questions using this modified guidance.

V. CONCLUSION

Developing a valid and readily useable rubric to assess student-generated MCQs was achievable. A further task is to apply this rubric to new sets of questions to further test its performance and utility.

Notes on Contributors

Dr. Rebecca Grainger is an academic rheumatologist in Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine of University of Otago Wellington. She is passionate about patient-focused care and medical education. She is responsible for the overall coordination and implementation of the study and assisted preparation for publication.

Emma Osborne is a professional practice fellow in student learning at the University of Otago. Her research interests include e-learning and teaching & learning in medical education. She initiated the process of rubric re-development, conducted qualitative analysis and was responsible for manuscript preparation.

Wei Dai is a research assistant in University of Otago. She is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Educational Psychology. Her research interest lies in the area of student engagement in technology-enhanced learning. She was responsible for the quantitative analysis and manuscript preparation.

Associate Professor Diane Kenwright is the Head of Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine of University of Otago Wellington. She is a registered pathologist and an enthusiastic medical educator. She approved this research and assisted the preparation for publication.

Ethical Approval

This research has been approved by the Human Ethics Committee of University of Otago (Level B), reference number D 16423.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the students in year four of University of Otago Wellington MBChB programme who participated the research.

Declaration of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest, including no financial, consultant, institutional and other relationships that might lead to bias.

Funding

This research had no specific grant funding from any funding agency.

References

Bartko, J. J. (1976). On various intraclass correlation reliability coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 83(5), 762-765. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.83.5.762.

Bates, S. P., Galloway, R. K., Riise, J., & Homer, D. (2014). Assessing the quality of a student-generated question repository. Physical Review Special Topics – Physics Education Research, 10(2), 020105.

Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 18(1), 57-75.

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.) (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives : the classification of educational goals. Handbook 1, cognitive domain. London, Longman.

Buckwalter, J. A., Schumacher, R., Albright, J. P., & Cooper, R. R. (1981). Use of an educational taxonomy for evaluation of cognitive performance. Academic Medicine, 56(2), 115-121.

Grainger, R., Dai, W., Osborne, E., & Kenwright, D. (2017). Self-generated multiple choice questions engaged medical students in active learning but not in a peer-instruction process. Paper presented at the 14th Asia Pacific Medical Education Conference (APMEC), Singapore.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Khan, M. U. , & Aljarallah, B. M. (2011). Evaluation of Modified Essay Questions (MEQ) and Multiple Choice Questions (MCQ) as a tool for Assessing the Cognitive Skills of Undergraduate Medical Students. International Journal of Health Sciences, 5(1), 39-43.

Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212-218. doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2.

McCoubrie, P. (2004). Improving the fairness of multiple-choice questions: a literature review. Medical Teacher, 26(8), 709-712. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590400013495.

McQueen, H. A., Shields, C., Finnegan, D. J., Higham, J., & Simmen, M. W. (2014). Peerwise provides significant academic benefits to biological science students across diverse learning tasks, but with minimal instructor intervention. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 42(5), 371-381. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20806.

Moseley, D., Baumfiled, V., Elliot, J., Gregson, M., Higgins, S., Miller, J., & Newton, D. P. (2005). Frameworks for thinking: A handbook for teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Palmer, E. J., & Devitt, P. G. (2007). Assessment of higher order cognitive skills in undergraduate education: modified essay or multiple choice questions? Research paper. BMC Medical Education, 7, 49-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-7-49.

Rush, B. R., Rankin, D. C., & White, B. J. (2016). The impact of item-writing flaws and item complexity on examination item difficulty and discrimination value. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 250. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0773-3.

Schuwirth, L. W. T., & Van Der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2004). Different written assessment methods: what can be said about their strengths and weaknesses? Medical Education, 38(9), 974-979. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01916.x.

Scouller, K. M., & Prosser, M. (1994). Students’ experiences in studying for multiple choice question examinations. Studies in Higher Education, 19(3), 267-279. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079412331381870.

University of Auckland. (2016). PeerWise. Retrieved from https://peerwise.cs.auckland.ac.nz/index.php.

Vanderbilt, A. A., Feldman, M., & Wood, I. K. (2013). Assessment in undergraduate medical education: a review of course exams. Medical Education Online, 18, 1-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.20438.

Veloski, J., Rabinowitz, H., Robeson, M., & Young, P. (1999). Patients don’t present with five choices: an alternative to multiple-choice tests in assessing physicians’ competence. Academic Medicine, 74(5), 539-546.

Young, A., & Shawl, S. J. (2013). Multiple Choice Testing for Introductory Astronomy: Design Theory Using Bloom’s Taxonomy. Astronomy Education Review, 12(1), 1-27. doi: https://doi.org/10.3847/AER2012027.

*Rebecca Grainger

Senior Lecturer

Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine

University of Otago Wellington

PO Box 7343, 23a Mein St

Newtown

Wellington South 6242

New Zealand

rebecca.grainger@otago.ac.nz

+64 4 385 5541

Published online: 2 May, TAPS 2018, 3(2), 6-18

DOI: https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2018-3-2/OA1046

Joanne Kua, Mark Chan, Jolene See Su Chen, David Ng & Wee Shiong Lim

Department of Geriatric Medicine, Institute of Geriatrics and Active Ageing, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

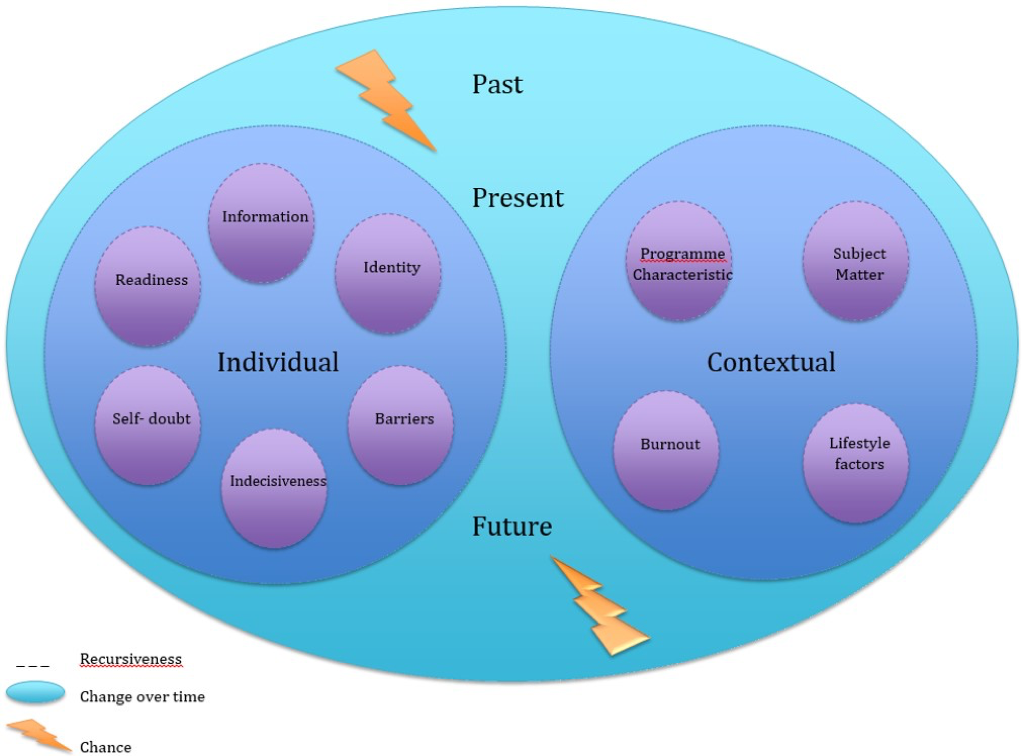

Aims: Career counselling is a complex process. Traditional career counselling is unidirectional in approach and ignores the impact and interactions of other factors. The Systems Theory Framework (STF) is an emerging framework that illustrates the dynamic and complex nature of career development. Our study aims to i) explore factors affecting senior residency (SR) subspecialty choices, and ii) determine the suitable utility of the STF in career counselling.

Methods: A prospective observational cohort study of internal medicine residents was done. Surveys were collected at three time points. The Specialty Indecision Scale (SIS) assesses the individual components and expert consensus group derived the questions for the contextual components. We measured burnout using the Mashlach Burnout Inventory. Process influences were assessed via thematic analysis of open-ended question at the 3rd survey.

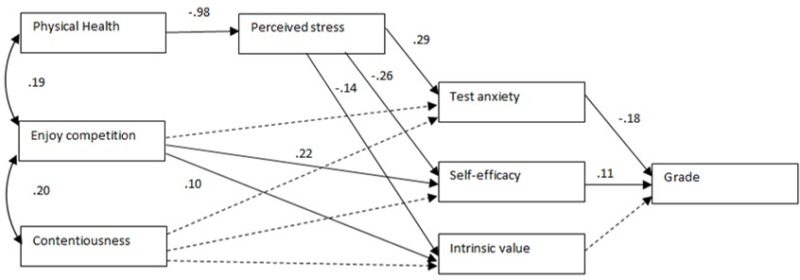

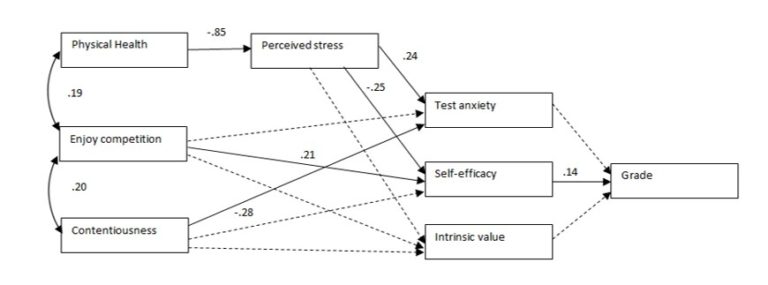

Results: 82 responses were collected. There was a trend towards older residents being ready to commit albeit not statistically significant. At year 1, overseas graduands (OR = 6.87, p= 0.02), lifestyle factors (t(29)=2.31, p=0.03, d= 0.91), individual factors of readiness (t(29) = -2.74, p=0.01, d= 1.08), indecisiveness (t(27)= -0.57, p=0.02, d= 0.99) and self- doubt (t(29)= -4.02, p=0.00, d= 1.54) predicted the resident’s ability to commit to SR. These factors change and being married (OR 4.49, p= 0.03) was the only factor by the 3rd survey. Male residents are more resolute in their choice (OR= 5.17, p= 0.02).

Conclusion: The resident’s choice of SR changes over time. The STF helps in understanding decision-making about subspecialty choices. Potential applications include: i) initiation of career counselling at year 1 and ii) reviewing unpopular SR subspecialties to increase their attractiveness.

Keywords: Internal Medicine Residents, Career Counselling, Senior Residency

Practice Highlights

- Career decision-making is a complex process and there is a need for a holistic approach to it.

- The Systems Theory Framework consists of a multifaceted range of content (individual and contextual factors) and process influences (change over time, recursiveness, chance) to illustrate the dynamic and complex nature of career development.

- The resident’s choice of senior residency changes over time throughout their residency. The factors that affect their subspecialty choice transit from individual factor of indecisiveness, self-doubt and readiness in year 1 to contextual factor of lifestyle by year 3.

- Male residents are more resolute in their choice of senior residency.

- Reasons for resident’s change of choice of senior residency include i) experience during rotation ii) lifestyle choices and iii) influences from peers and seniors.

I. INTRODUCTION

The choice of senior residency training is an important decision for internal medicine residents. There is a rich array of options ranging from sub-specializing in a chosen field among the many areas in internal medicine, through to continuing as a general internist. This is not an easy process and not surprisingly, there is great interest in examining the factors that influence this decision. Understanding what is important from the perspectives of residents will be helpful for ‘unpopular’ subspecialties as they seek to transform the subspecialty to become more attractive by incorporating factors that residents look for in their choice.